Despite its classic clinical presentation, and even when confirmed by compatible imaging findings of a herniated disc, the radiculopathy diagnosis provides only limited assistance for making decisions about treatment. The 2003 Medicare data revealed an eightfold variation in the rates of lumbar laminectomy and discectomy across geographic regions. In an effort to address this uncertainty in care, this article describes the management paradigm known as Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy and its usefulness in decision-making for patients with lumbar radiculopathies, and reviews the relevant literature.

A radiculopathy is a fairly precise diagnosis compared with other painful lumbar disorders. Most low back pain is lumped into the “nonspecific” category for which no definitive diagnosis is possible. However, despite its classic clinical presentation, and even when confirmed by compatible imaging findings of a herniated disc, the radiculopathy diagnosis provides only limited assistance for making decisions about treatment. Surgery, on average, provides quite favorable and predictable relief of radicular pain in a relatively short period of time, while good long-term outcomes with nonsurgical treatment are, again on average, also achievable, with far less risk, but recovery takes much longer.

The phrase “on average” is a key point here. Most data on which clinicians depend for guidance helps with the “average” patient; but individual patients are rarely “average.” So how do clinicians and their patients make decisions regarding treatment?

Given varying preferences among patients regarding surgical versus nonsurgical care, shared decision-making programs are widely advocated for assistance, but are still in limited use. These programs focus on presenting a balanced view of the treatment options, with each patient’s personal life situation playing an important role in their preference. But do they provide all the information patients would like and therefore should receive?

Nowhere is the high variation in this decision-making more vivid than in the 2003 Medicare data that revealed an eightfold variation in the rates of lumbar laminectomy and discectomy across geographic regions. With no evidence of any variation between these regions regarding the severity of the disc pathology, the ability to make the diagnosis, and patient preferences and satisfaction, the cause of this variation has been attributed to “supply-driven care,” specifically a greater supply of surgeons in high-rate areas.

In an effort to address this uncertainty in care, this article describes the management paradigm known as Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT) and its usefulness in decision-making for patients with lumbar radiculopathies, and reviews the relevant literature.

The MDT examination provides information about the characteristics of the pain generator unavailable from any other form of assessment, including more conventional clinical examination tests and even our most advanced forms of spinal imaging. Determining the dynamic mechanical characteristics of a symptomatic herniated lumbar disc enables a far higher level of precision and certainty in decision-making than merely determining the anatomic diagnosis.

This form of dynamic spinal assessment has relevance to both axial pain and sciatica due to its unique ability to determine the potential “reversibility” of symptoms and the substantial evidence that it is related to pain-generating disc pathologies. Such reversibility is very often detected even late in the game, after other forms of conservative treatments have failed. For many, MDT’s value is best documented in studies showing that patients who do not receive this form of assessment and treatment often undergo unnecessary surgery.

Overview of mechanical diagnosis and therapy

MDT, the focus of this article, was developed by Robin McKenzie, a New Zealand physiotherapist, 50 years ago. It is well described in many other publications, most notably in McKenzie’s textbook.

In essence, this low back management paradigm begins with a unique clinical assessment process that provides precise patient-specific information that directs treatment, which can then be customized to each individual’s underlying pain generator. In such individualized care, the “average” patient becomes irrelevant. Abundant evidence makes the case that the clinical findings from this assessment provide much more precise information about the underlying pathology than can be ascertained via conventional clinical testing and our most sophisticated imaging studies.

During the assessment, the patient’s history often reveals that their symptoms worsen with one direction of lumbar bending or positioning and improves with another. For example, many individuals’ symptoms worsen with lumbar flexion activities such as bending, lifting, sneezing, and prolonged slouched sitting, and improve when erect, most notably while walking.

In addition to the conventional physical examination including neural evaluation, patients’ low backs are then essentially taken for a mechanical test-drive by the MDT examiner to determine precisely what aggravates and what relieves their symptoms, looking for a correlation with the patient’s history.

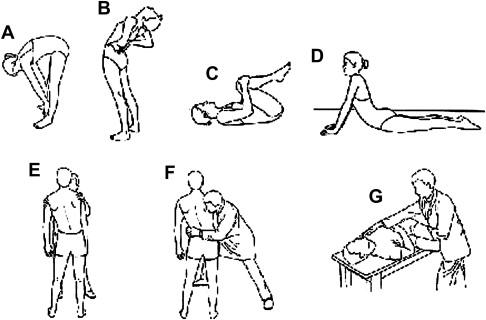

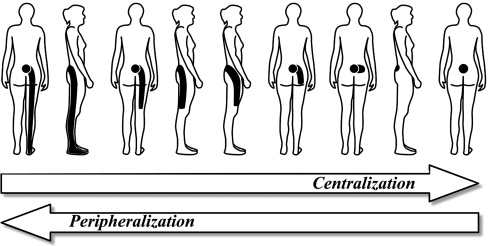

Specifically, they are directed to perform, to whatever extent their pain will allow, repeated end-range lumbar test movements and static positioning in different directions of lumbar bending to determine what effect these tests have on the location and intensity of their pain, regardless of whether it is axial pain only or pain referred away from the low back, including radicular pain to the foot ( Fig. 1 ). A single direction of testing, that is, the patient’s “directional preference,” is often elicited that will bring a beneficial pain response in the form of either pain centralization (see later discussion) ( Fig. 2 ) in the case of referred or radicular pain, or pain abolition in the case of axial pain. Other directions of testing typically aggravate the pain or even cause it to move further distally, called “peripheralization.”

So for those in whom a directional preference is found, the most common preferred direction is lumbar extension, with a smaller number needing laterally directed movements, and a very small group rapidly recovering with lumbar flexion end-range movements.

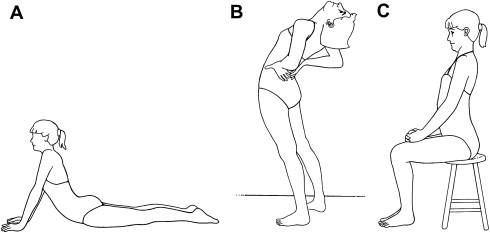

Once the patient is evaluated and classified, the MDT examiner then becomes a teacher and coach, helping each patient to learn how to self-manage his or her problem with strategic use of directional exercises every few hours performed in their single beneficial direction ( Fig. 3 ). The patients quickly become enabled and empowered to eliminate and then prevent the return of their pain. In addition, they must temporarily avoid bending or positioning the spine for a few days in the opposite direction (see Fig. 3 ).

Patients quickly learn that they are in control of their own pain, by knowing how to turn it on and off, depending on what direction they move or position themselves. This knowledge provides extraordinary insight into the mechanical characteristics of their problem that enables them to either prevent, or at least promptly address, any recurrent pain in the weeks and months ahead, as well as recognize why the pain returned.

Two informative clinical findings

Pain centralization and directional preference are 2 clinical findings that are fascinating in large part because they are dynamic. Spine care clinicians are unfamiliar with dynamic mechanisms of pain production and relief. These findings can only be consistently elicited using this MDT dynamic examination. It is also noteworthy that when patients promptly report improvements in their pain intensity and location, they also demonstrate a simultaneous improvement in their lumbar range of motion.

Both centralization and directional preference have been studied extensively for the past 20 years. These studies show that it is highly likely that the spinal loading tests that elicit centralization and directional preference do so because they mechanically influence and alter the underlying pain-generating pathology.

Pain centralization is defined as a progressive retreat of referred or radicular pain back toward or to the center or midline of the lumbar spine, usually as a result of the patient performing repeated end-range movement in a single direction (see Fig. 2 ). Other directions of repeated-movement end-range testing in the same patient will not affect the pain or, much more commonly, will aggravate it in some way, such as by increasing its intensity or pushing it further away from the lumbar midline, that is, peripheralization. The single direction of testing that centralizes or often even abolishes the pain is referred to as the patient’s directional preference.

Two informative clinical findings

Pain centralization and directional preference are 2 clinical findings that are fascinating in large part because they are dynamic. Spine care clinicians are unfamiliar with dynamic mechanisms of pain production and relief. These findings can only be consistently elicited using this MDT dynamic examination. It is also noteworthy that when patients promptly report improvements in their pain intensity and location, they also demonstrate a simultaneous improvement in their lumbar range of motion.

Both centralization and directional preference have been studied extensively for the past 20 years. These studies show that it is highly likely that the spinal loading tests that elicit centralization and directional preference do so because they mechanically influence and alter the underlying pain-generating pathology.

Pain centralization is defined as a progressive retreat of referred or radicular pain back toward or to the center or midline of the lumbar spine, usually as a result of the patient performing repeated end-range movement in a single direction (see Fig. 2 ). Other directions of repeated-movement end-range testing in the same patient will not affect the pain or, much more commonly, will aggravate it in some way, such as by increasing its intensity or pushing it further away from the lumbar midline, that is, peripheralization. The single direction of testing that centralizes or often even abolishes the pain is referred to as the patient’s directional preference.

Research

Studies of these two clinical findings are numerous and fall into 3 major categories: prevalence, reliability, and validity. The validity studies are of different types as well: outcome prediction, outcome efficacy, and construct validity. These studies include a wide range of lumbar patients including acute-to-chronic, axial pain only, and sciatica/radiculopathy, and come from at least 7 countries. Some studies focus specifically on radiculopathies.

Prevalence Studies

Since 1990, at least 10 studies have reported on the high prevalence of centralization and directional preference in a wide range of study populations. Overall, the reported prevalence of these two findings has been 70% to 87% across acute low back pain studies and 32% to 52% with chronic or radicular patients.

Reliability

The value of any clinical test is fundamentally based on its interexaminer reliability. Without reliability there can be no validity, that is, the test is irrelevant. Such studies regarding centralization, directional preference, and MDT patient classification report very acceptable levels of reliability with kappa values greater than 0.6 for identifying centralization and directional preference. This reliability is superior to any other form of clinical examination, including palpation and observation.

Predictive Validity

Many cohort studies have investigated the impact of identifying centralization and directional preference on patient outcomes. An excellent treatment outcome routinely is reported by patients in whom a directional preference and pain centralization are found, as long as treatment is guided by the patient’s directional preference findings. In these same studies, outcomes were far less successful in those in whom a directional preference was not found.

But do centralization and directional preference merely identify those who have a good prognosis with most any form of treatment? There are 2 important considerations.

First, if that were the case, there should be no chronic low back pain patients with a directional preference because they would have all recovered with other forms of treatment, or with no particular treatment, long before they became chronic. But the prevalence data show that up to 50% of chronic patients still have a directional preference that, once identified, directs a specific directional exercise treatment defined by the assessment findings that leads to excellent outcomes. These patients needed a specific form of directional end-range treatment to correct a problem that had been reversible all along, but was never given the required treatment.

Second, determining whether other treatments might also be beneficial for this large subgroup requires efficacy studies that randomize this large group of directional preference patients to different treatments.

Efficacy Validity

There are now 6 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) targeting this large subgroup of patients who demonstrated the clinical findings of pain centralization and directional preference during their baseline evaluation. These 6 studies compared the standard MDT treatment of teaching directionally matching exercises and posture modifications with alternative treatments such as stabilization exercises, manual therapy, manipulation, joint mobilization, exercising in the opposite direction to the patient’s preference, or guideline-based treatment.

All 6 RCTs show that treating directional preference patients with appropriate directional exercises produced significantly better outcomes compared with any of the treatment alternatives.

While none of these RCTs focused exclusively on patients with radiculopathies, 34% of the Long and colleagues study sample had pain below the knee, half of whom also had neural deficits. Across all directional preference subgroups based on age, duration, and pain location, including those with a radiculopathy, all 6 clinical outcome measures were excellent when directional exercise treatment matched patients’ baseline directional preference. For example, patients’ self-rated improvement with matching directional exercises was 95% at just 2 weeks, far superior to either guideline-based care (42%) or exercising in the opposite direction from patients’ directional preference (23%). Even for these directional preference patients, shown to have such a good prognosis in so many other studies, how they are treated makes a substantial difference. This finding was even clearer when 15% of the patients in the 2 nonmatching study groups, all of whom had a directional preference at their baseline evaluation, reported worsening.

A separately published study reported that a cross-over option was offered to those patients in this same RCT who were initially assigned to an unmatched treatment and did not do well. Of the 96 patients who were then crossed over to matching exercises, 84% reported rapid recoveries after just 2 weeks, once again with significant improvement in all 6 outcome measures.

Construct Validity

There is considerable evidence that the pain-generating structure responsible for most pain centralization and directional preference is the intervertebral disc, regardless of the pain being axial or radiating fully down the leg to the foot with neural deficits.

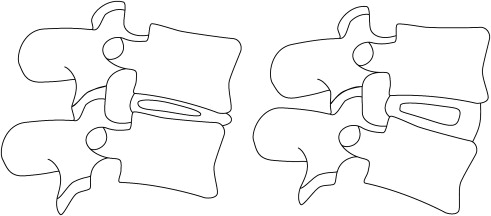

Numerous imaging and cadaveric studies demonstrate directional mechanical characteristics of intervertebral discs and their nuclei. In normal discs, anterior or flexion loads cause the nucleus to migrate away from the load in a posterior direction, and vice versa with extension loading ( Fig. 4 ). The nucleus must change its location within the disc to enable the disc to change its shape in order for the spine to bend. The nucleus must move out of the way to enable the edges of the adjacent vertebral bodies to approximate as the spine bends.