McLaughlin Procedure for Acute and Chronic Posterior Dislocations

Joseph D. Zuckerman

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

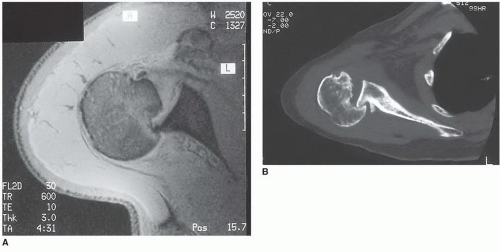

Posterior glenohumeral dislocations can result in anteromedial humeral head impression fractures (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). These impression fractures occur as a result of contact between the posterior rim of the glenoid and the anteromedial portion of the humeral head (Fig. 24-1). They are often referred to as reverse Hill-Sachs defects (the posterolateral humeral head defects commonly found in association with anterior glenohumeral dislocations).

The size of the anteromedial defects can be quite variable. Acute posterior dislocations that are reduced promptly and properly will usually result in small and often insignificant defects (Fig. 24-1A). However, multiple episodes of posterior dislocation, even if reduced promptly, can result in a larger defect. In addition, prolonged contact between the posterior glenoid and the humeral head, as occurs in chronic unreduced dislocations, may result in defects that encompass a significant portion of the humeral head (Fig. 24-1B). In both situations, the bony defect can become a factor causing recurrent instability. When this occurs, operative management is often directed at correcting the anteromedial humeral head defect.

The McLaughlin procedure is defined as a transfer of the subscapularis tendon into an anteromedial humeral head defect that resulted from either an acute or a chronic posterior glenohumeral dislocation (7, 8, 9). The modified McLaughlin procedure consists of a transfer of the lesser tuberosity with the subscapularis attached into the anteromedial humeral head defect (2, 3, 4, 10).

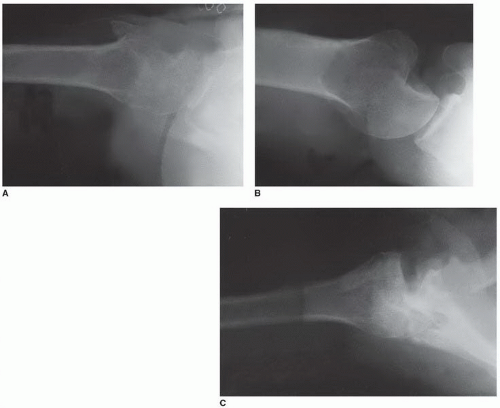

In acute dislocations, defects of less than 20% will probably not contribute to recurrent instability. However, in chronic dislocations, a defect of even this size may require subscapularis transfer at the time of open reduction (Fig. 24-2A). Defects of 20% to 40% are usually found in association with chronic dislocations (Fig. 24-2B). Following open reduction of these injuries, a subscapularis transfer or a lesser tuberosity transfer will be required to maintain stability. Defects encompassing more than 40% of the humeral head will usually require prosthetic replacement (Fig. 24-2C).

The indications for the subscapularis transfer as opposed to the lesser tuberosity transfer are important to understand. In general, subscapularis transfer alone is sufficient for small humeral head defects (up to 20%) in which the soft tissue alone is sufficient to fill the defect. However, larger defects (greater than 20%) will require lesser tuberosity transfer with the subscapularis attached to adequately fill the bony defect and prevent recurrent instability.

There are two important contraindications to the McLaughlin and modified McLaughlin procedures. These include (a) an anteromedial humeral head defect that encompasses more than 40% of the articular surface and (b) cases of long-standing dislocation in which there is significant deterioration of the remaining articular cartilage of the humeral head or glenoid. In both these situations, subscapularis transfer or lesser tuberosity transfer is contraindicated and prosthetic replacement is preferred. It is important to recognize that these indications and contraindications are truly guidelines and that the treatment of each case should be determined individually by considering any and all relevant patient factors.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The preoperative evaluation of the patient should include a careful assessment of the etiology of the posterior instability. An underlying seizure disorder is often present and will require consultation with a neurologist. The goal of this consultation is first to adequately control the seizures to avoid additional episodes during the postoperative period and second to identify any treatable or correctable etiology of the seizure disorder.

The chronicity of the dislocation should also be assessed preoperatively, because this will have a few important implications. First, it will indicate the chance of achieving a successful closed reduction. Second, it will provide some indication of the difficulty of achieving an open reduction. Third, it will indicate the status of the remaining articular cartilage. A careful history from the patient and relatives will generally provide a reasonably accurate estimation of the duration of the dislocation.

The patient with a locked posterior dislocation presents with characteristic findings. There is a history of trauma, either recognized by the patient or unrecognized, as may occur with a seizure. The patient may have been seen in an emergency department and may have had radiographs taken. Up to 70% of acute posterior dislocations are unrecognized by the initial examiner, usually because radiographs have been inadequate for diagnosis or have been interpreted incorrectly. In many cases, an axillary radiograph has never been obtained. This diagnosis will not be overlooked if a well-done axillary radiograph is obtained and interpreted correctly (Fig. 24-3).

The patient frequently presents with pain and virtually always notes loss of motion. Whatever the history, the presenting physical findings are classic. Because of the locked position of the humeral head posteriorly, there is frequently a flattened appearance to the anterior shoulder and a fullness posteriorly. The hallmark physical finding, however, is the inability to externally rotate the humerus because of the locked posterior position of the humeral head posteriorly. These findings are present whether the dislocation is acute or long-standing and chronic. A locked posterior dislocation, if unrecognized, may result in chronic clinical and radiographic changes.

The most important aspect of the examination is the determination of the size of the humeral head defect. The size of the defect (expressed as a percentage of the humeral head articular surface) is the key factor in determining treatment and can be determined radiographically. The standard trauma series, including most importantly the axillary view (Fig. 24-2), provides a reliable indication of the size of the defect. However, a computed tomography scan is particularly helpful for accurate determination of the size of the defect (Fig. 24-1B).

Based on the information provided, the first decision is whether a transfer procedure is indicated. Generally, for defects that involve less than 40% of the articular surface, a transfer procedure is preferred. If this is the case, the second decision is whether a subscapularis transfer or a lesser tuberosity transfer is preferred. This decision is based primarily on the size of the defect as noted previously.

SURGERY

This procedure can be performed under general or regional anesthesia as long as optimal muscle relaxation can be achieved. The operating table should be placed in a beach-chair position with the head elevated approximately 30 degrees (Fig. 24-4). Use of a shoulder arthroscopy positioner facilitates proper positioning of the patient. The mobility of the involved shoulder and upper extremity should not be limited by the operating table. The area of skin preparation should include the entire upper extremity and as much of the shoulder girdle as possible. The preparation should extend to the base of the neck as well as anteriorly and posteriorly to allow complete access to the glenohumeral joint.

An anterior deltopectoral approach is preferred. The skin incision is oriented obliquely starting just medial to the acromioclavicular joint and extending distally and laterally to the insertion of the deltoid muscle (Fig. 24-5). An anterior axillary incision can also be used; it is placed in line with the axillary skin crease. The skin and subcutaneous tissues are divided, and medial and lateral flaps are developed at the muscle layer. Preparation of these flaps will improve the surgical exposure. The deltopectoral interval is then determined by identifying the junction of the fibers of the deltoid, which run in a lateral and distal direction, and distinguishing them from the fibers of the pectoralis major, which run in a more transverse direction. The interval is also marked by a fat stripe that covers the cephalic vein. Careful dissection in this area will allow identification of the cephalic vein. Retraction of the vein medially or laterally is generally a matter of the surgeon’s preference. Most of the muscle branches enter the vein from the deltoid side; therefore, mobilization laterally with the deltoid is often preferred. However, in this situation, the cephalic vein crosses the interval superiorly, which puts it at risk for injury from retraction during the procedure. For this reason, some surgeons prefer medial mobilization. I have found that the initial dissection of the cephalic vein usually indicates that the vein is more easily mobilized in one direction or the other, based on the specific anatomy encountered. Regardless of which direction the vein is retracted, care should be taken to preserve the vein during the procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree