Management of Chronic Glenohumeral Dislocations

Michael T. Lu

Joseph A. Abboud

INTRODUCTION

While describing his experiences with chronic glenohumeral dislocations, Cubbins stated, “it is difficult to understand how a condition so clear-cut and with such outstanding symptoms can be overlooked and remain undiagnosed until dislocation has become ancient.”13 Indeed, orthopedic surgeons have long contemplated the treatment of chronic glenohumeral dislocations, as the management of these disorders can be quite challenging.3,5 When considering that there is no standardized duration that qualifies for a “chronic” dislocation, it is no wonder that the optimal management of these injuries has not been clearly defined.

Multiple techniques have been described for the treatment of chronic glenohumeral dislocations, including supervised neglect, closed reduction, arthroscopic-assisted reduction, resection arthroplasty, glenohumeral arthrodesis, open reduction with bone/soft-tissue transfers, allograft reconstruction, prosthetic arthroplasty, and rotational osteotomy.1,2,3,5,7,8,9,10 and 11,13,15,16,17,18 and 19,21,22,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 and 37,39,40 and 41,44,46,47,49,50,52,53,54 and 55,57,58,61,62 Each case must be considered individually, paying careful attention to soft-tissue status, bony defects, articular surface integrity, chronicity, patient compliance, patient dysfunction, and patient comorbidities.3,11,17,47,49 In this chapter we will discuss the management of chronic glenohumeral dislocations, particularly the

clinical evaluation, nonoperative treatment methods, operative techniques, and their respective outcomes as reported in the literature.

clinical evaluation, nonoperative treatment methods, operative techniques, and their respective outcomes as reported in the literature.

DEFINITION/EPIDEMIOLOGY

There is no clear consensus on the duration that qualifies as a “chronic” dislocation. The use of inexact terms such as “old,” “neglected,” “ancient,” and “locked” makes precise communication even more challenging.3,13,21,50 The qualification of chronic glenohumeral dislocations in the literature has varied widely, ranging from those untreated for 24 hours to those that have been dislocated for at least 6 months.32,50 Some authors have suggested that any dislocation that is not initially recognized and receives delayed treatment should be considered “chronic.”49

Just as the definition of chronic dislocations is unclear, so, too, is the epidemiology surrounding these dislocations. Rowe and Zarins found nearly twice as many chronic anterior dislocations as posterior dislocations (65% anterior, 35% posterior) in a poll of 208 orthopedic surgeons.47 This finding is contrasted by a recent review of the English literature in which 12 series of patients with a total of 268 chronic dislocations were examined.49 Of these, 41% were anterior dislocations and 59% were posterior. However, the authors stated that it is virtually impossible to determine the true incidence in the context of all patients who sustain glenohumeral dislocations.

Some surgeons have suggested that chronic posterior dislocations may be more common than their anterior counterparts because of the radiographic familiarity that orthopedic surgeons, radiologists, and emergency physicians have with acute anterior dislocations, prompting earlier treatment.1,2,47,50 In addition, chronic glenohumeral dislocations often arise in the poly-traumatized patient with multiple distracting injuries, allowing a glenohumeral dislocation to be overlooked.33 These patients may not be able to communicate a thorough history (e.g., brain injury, sedation, postictal) or may not seek immediate medical attention (e.g., an alcoholic who falls frequently and has new onset shoulder pain and decreased motion).17

CLINICAL EVALUATION

History

Patients may present with restricted glenohumeral motion and varying degrees of pain (depending on chronicity). It is this loss of motion and subsequent dysfunction that often prompts patients to seek medical attention.22,49 The patient must be carefully questioned about any history of trauma, seizure, or electrical shock.11,19,29,47,50 Even if a patient describes a traumatic event but does not specifically recall a glenohumeral dislocation, this may be due to distracting injuries that overshadowed the shoulder injury.

The specific timing of the injury is of crucial importance as it has significant treatment implications.3,11,33,49 Previous treatments, if any, are also important. Patients may have sought prior medical treatment for an undiagnosed glenohumeral dislocation, only to be diagnosed with adhesive capsulitis, subacromial bursitis, or rotator cuff tendinitis.11,23,47,50 Furthermore, the patient’s age, hand dominance, activity level, occupation, level of dysfunction, expectations, and medical comorbidities must also be considered.

Physical Examination

As with all orthopedic evaluations, the initial component of the physical examination is visual inspection. Both shoulder girdles must be assessed from anterior, posterior, lateral, and superior vantage points. Asymmetric contours about the shoulder girdle can be the first clue to a glenohumeral dislocation. Chronic dislocations accompanied by muscular atrophy often have the most pronounced findings upon inspection. Anterior dislocations can be distinguished by an anterior fullness, a relative posterior flattening of the shoulder, and a squaring of the posterolateral acromion. Conversely, posterior dislocations can be distinguished by a posterior fullness and a relative anterior flattening of the shoulder. Additional information can be gathered by inspecting the acromion and coracoid for asymmetric prominences. However, noting asymmetries may prove challenging in obese patients, muscular patients, or those with bilateral dislocations.

Palpation about the shoulder girdle can also provide valuable information about the direction of the dislocation. Muscular atrophy in the face of these chronic dislocations often facilitates this portion of the physical examination. The humeral head can be palpated in the subcoracoid region in anterior dislocations. The posterior shoulder musculature can make palpation of the humeral head as it resides posterior to the acromion somewhat challenging.

Despite frequent complaints of loss of motion by patients with chronic glenohumeral dislocations, patients may present with functional ranges of motion due to impression fractures, progressive bony erosions, and scapulothoracic compensation.23,49 Forward elevation, abduction, and internal rotation are restricted in anterior dislocations. Posterior dislocations classically have decreased external rotation, abduction, and forward elevation.11

Motor and sensory testing of the entire upper extremity can help identify a brachial plexopathy. Careful attention must be paid to assessing the function of the axillary nerve, especially in the face of a chronic anterior dislocation. Strength testing may be normal unless there is neurologic compromise or significant muscular atrophy. Specific testing of the rotator cuff is often difficult, especially when hampered by decreased range of motion. Full thickness tears of the rotator cuff are not uncommon in the setting of chronic glenohumeral dislocations.38,47

Imaging

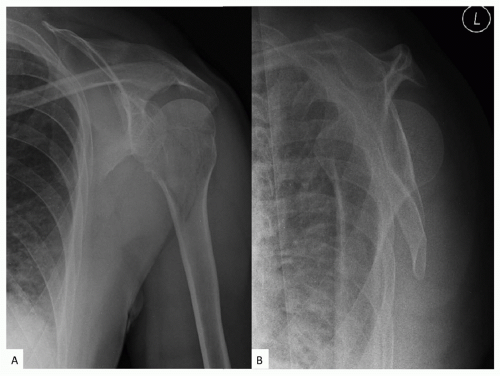

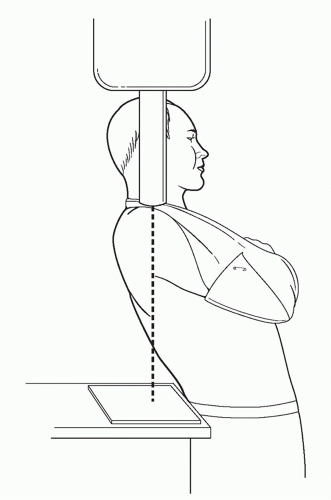

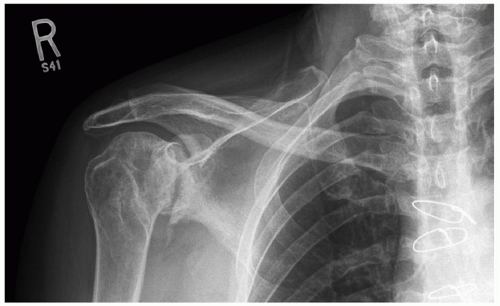

Radiographic evaluation begins with a complete plain radiograph trauma series of the affected shoulder. This series, at minimum, consists of an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph in the scapular plane, an axillary view, and an outlet/scapular-Y view. Radiographic images in orthogonal planes are crucial to assess the direction of the dislocation and the status of bony defects. The importance of a complete radiographic series, particularly the axillary view, cannot be overstated.23,33 Subtle dislocations, especially those dislocated in a posterior direction, may be especially difficult to diagnose without a complete radiographic series or three-dimensional imaging (Figs. 8-1 and 8-2).23,50,60 Additional specialized radiographic views can be obtained, if necessary for a complete evaluation

(e.g., Velpeau view for patients who cannot adequately abduct the arm to obtain an axillary view) (Figs. 8-3 and 8-4).4

(e.g., Velpeau view for patients who cannot adequately abduct the arm to obtain an axillary view) (Figs. 8-3 and 8-4).4

The humeral head in anterior dislocations is typically positioned anterior and inferior to the glenoid. This can be confirmed on the axillary/outlet views and AP view, respectively. Careful evaluation of the axillary view can reveal bony erosions or compression fractures of the glenoid and humeral head, respectively.24,34 Glenoid rim fractures can also be seen on the axillary or outlet views. Chronic dislocations are often distinguishable from acute dislocations by the presence of reactive bone formation around the glenoid neck or ossification of the rotator cuff tendons/capsule.17

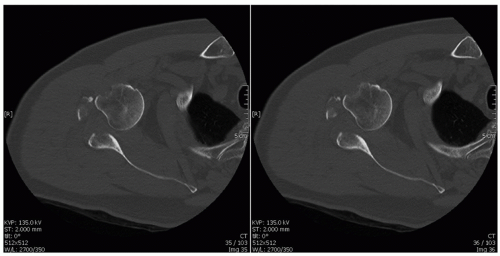

With posterior dislocations, the AP radiograph may show only a subtle overlap of the humeral head and glenoid, which may be easily disregarded as poor radiographic technique. Again, correlation with an axillary view to confirm the position of the humeral head is of critical importance (Figs. 8-4, 8-5 and 8-6). Bony erosions of the humeral head and glenoid should be evaluated. As with anterior dislocations, chronic posterior dislocations are often accompanied by reactive bone formation about the glenoid neck and ossification of the soft tissues that intimately surround the shoulder. Additionally, the humeral head may resemble the silhouette of an incandescent light bulb (i.e., light bulb sign) adjacent to a vacant glenoid on the AP radiograph.

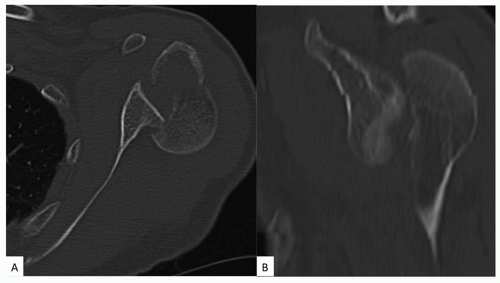

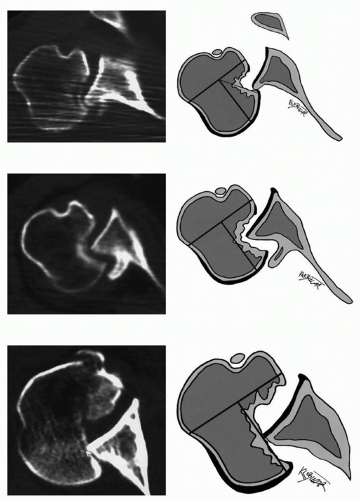

Computed tomography (CT) is another valuable tool in the armamentarium to evaluate glenohumeral dislocations.2,11,18,23,30,33,56 Three-dimensional reconstruction images are particularly useful for assessing bony defects and articular involvement (Fig. 8-7).11,26 These factors are critical

in determining management and for preoperative planning, if necessary.30,33 CT evaluation should be performed in patients who cannot be adequately evaluated with plain radiographs (e.g., difficulty with proper positioning).2,30

in determining management and for preoperative planning, if necessary.30,33 CT evaluation should be performed in patients who cannot be adequately evaluated with plain radiographs (e.g., difficulty with proper positioning).2,30

FIGURE 8-4. Anteroposterior radiograph revealing a subtle overlap of the humeral head on the glenoid in the face of severe glenohumeral arthritis. (Image courtesy of Suzanne L. Miller, MD.) |

FIGURE 8-5. An axillary radiograph of the same shoulder clearly demonstrating a posterior dislocation with a large humeral head defect. (Image courtesy of Suzanne L. Miller, MD.) |

The role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is unclear.25 While MRI does provide three-dimensional information, bony architecture is better evaluated on CT. The status of soft-tissue structures (e.g., rotator cuff, labrum, glenohumeral ligaments, and long head biceps tendon) is better evaluated with MRI (Figs. 8-8, 8-9, and 8-10).18,33 MRI may be especially useful in patients over 40 years of age due to their higher rate of rotator cuff tears after shoulder dislocation.38

Additional Diagnostic Studies

The incidence of neurovascular compromise in chronic dislocations is uncertain. However, in the event of neurovascular injury, electrodiagnostic studies and nerve conduction velocity testing should be considered. Serial studies can be compared to monitor potential nerve function recovery. Electrodiagnostic studies may be especially helpful to document preoperative nerve function in patients who undergo surgery. This will help to avoid considering a postoperative neurologic deficit as a complication of surgery. The axillary nerve may be especially at risk during surgery.37,47,50

The incidence of vascular embarrassment in chronic glenohumeral dislocations is low. If there is concern for a potential vascular injury, then consultation of a vascular specialist and consideration of an angiogram may be warranted. The treating physician should also keep in mind that vascular injury can occur during attempted reduction maneuvers.51 This may be especially true in elderly patients who have lost the elasticity of their vascular endothelium.33

Rating System

Rowe and Zarins proposed a rating system based on 100 units to facilitate comparative studies on the treatment of chronic glenohumeral dislocations.47 The rating system weighs pain (maximum: 30 units), motion (maximum: 40 units), and function (maximum: 30 units). The final outcomes are considered excellent, good, fair, or poor depending on the total score (Table 8-1).

TREATMENT

General Principles

A wide variety of treatment options have been developed for the management of chronic glenohumeral dislocations. These include both nonoperative and surgical techniques. Multiple factors must be considered when evaluating each chronic glenohumeral dislocation: patient comorbidities; patient dysfunction; patient compliance; patient expectations; chronicity of the dislocation; status of articular cartilage; bony defects (both humeral head and glenoid); direction of the dislocation; and soft-tissue status.3,11,17,33,47 Each of these factors must be considered when developing an individualized treatment plan for each chronic glenohumeral dislocation.

Additionally, any underlying causes that prompted the dislocation must be addressed and controlled, if possible (e.g., seizure disorder, alcoholism, and balance disturbances).2,11 When deciding between operative and nonoperative treatment, the treating physician must keep in mind that the most reliable benefit from surgical intervention is improved pain relief.33

Additionally, any underlying causes that prompted the dislocation must be addressed and controlled, if possible (e.g., seizure disorder, alcoholism, and balance disturbances).2,11 When deciding between operative and nonoperative treatment, the treating physician must keep in mind that the most reliable benefit from surgical intervention is improved pain relief.33

NONOPERATIVE TREATMENT

In general, low demand patients who have minimal discomfort and minimal functional deficits may be considered for nonoperative treatment.8,11,17,33,47,50 Alternatively, patients who have medical comorbidities that would place them at unreasonable surgical risk or who are unable to comply with the postoperative rehabilitation/restrictions may be considered for nonoperative treatment.11,23

CLOSED REDUCTION

The most important factor when considering closed reduction of a chronic glenohumeral dislocation is the acuity of the injury.3,11,33,49 Successful closed reduction following 8 weeks of dislocation has been reported.50 A recent meta-analysis of 268 chronic dislocations found that 50 patients were treated with closed reduction.49 Twenty-seven patients had satisfactory to good results. The patients with satisfactory to good outcomes were dislocated for less than 4 weeks.

Careful evaluation of high-quality radiographs or advanced imaging studies can yield valuable information about bony defects. Chronic dislocations that have more than 20% to 25% articular involvement are more likely to remain unstable following closed reduction.11,23,49 These chronic dislocations may be best treated with an attempted closed reduction in the operating room followed by conversion to surgical treatment if the shoulder remains unstable.

Attempted closed reduction of chronic dislocations may require additional sedation/analgesia that their acute counterparts may not need. Again, consideration of attempted closed reduction in the operating room with the aid of general anesthesia and muscle relaxation/paralysis may be warranted. The reduction maneuver depends on the direction of the dislocation.

A similar technique can be employed to reduce both acute and chronic anterior glenohumeral dislocations. Our preferred technique is the use of gentle longitudinal traction on the abducted and flexed arm with countertraction on the thorax with the patient supine. Slowly bringing the arm from internal rotation to external rotation may help disengage any bony defects. One must be careful to avoid overly forceful movements or levering the humeral head on the glenoid as these maneuvers may result in iatrogenic fracture (Figs. 8-11 and 8-12).

Closed reduction of a chronic posterior glenohumeral dislocation can be very challenging. With the patient supine, the arm is gently internally rotated to stretch the posterior soft tissues. Longitudinal and lateral traction are placed on the arm to disengage the humeral head from the glenoid. Once disimpacted, the humeral head is gently lifted back into the glenoid fossa and externally rotated. External rotation is avoided until the humeral head has been disimpacted to lessen the risk of iatrogenic fracture.

When a successful closed reduction is achieved, the shoulder must be assessed for stability through a range of motion. If the shoulder remains stable through a functional range, the patient is immobilized in a stable position for 3 to 6 weeks.33,47,49 Temporary supplemental stabilization of the acromion to the humeral head with Kirschner wires or the humerus to the glenoid with screw fixation can help maintain the reduction.21,37

Serial radiographs should be obtained to confirm a concentric reduction within the first week. Progressive physical therapy focusing on stretching and strengthening can begin as the patient is weaned from immobilization after 3 to 6 weeks. Patients should be thoroughly educated on provocative positions of the shoulder that would place them at increased risk of repeat dislocation. Additionally, factors that may have prompted the dislocation must be addressed (seizure disorder, alcoholism, etc.).2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree