Management of Bone Loss in Primary Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty

Jason J. Scalise

Joseph P. Iannotti

INTRODUCTION

The approach to and treatment of rotator cuff tear arthropathy has seen extensive changes over the last two decades with the availability of the reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RSA). Prior to the widespread use of the RSA prosthesis, the treatment options were often limited to hemiarthroplasty or nonsurgical modalities for which the clinical outcomes were often unsatisfactory. In some severe cases of rotator cuff deficient arthritis, substantial glenoid bone loss may be present. Recognizing common patterns of bone loss in this group of patients and an understanding of how to address such deficiencies will greatly help the surgeon obtain the benefits of RSA and maximize clinical outcomes and the longevity of the prosthesis.

PATHOMECHANICS

Under normal conditions, the humeral head is centered within the glenoid fossa secondary to the synchronous forces of the rotator cuff and deltoid muscles. Significant deficiency of the rotator cuff leads to superior migration of the humeral head within the glenoid fossa due to the unbalanced vector of the deltoid muscle.

Ongoing contact of the humeral head with superior portion of the glenoid may lead to eccentric wear of the glenoid. In severe cases, large erosions of the superior portion of the glenoid may occur.

Rheumatoid disease is frequently implicated in arthritis of the shoulder as a cause of both rotator cuff deficiency and glenoid bone destruction. In some cases of rheumatoid disease, centralized glenoid bone loss is more prevalent. The propagation of pathologic synovial tissue may lead to widespread glenoid destruction. The combination of rotator cuff deficiency and substantial glenoid bone loss represents a particular challenge for the treating surgeon.

CLASSIFICATION

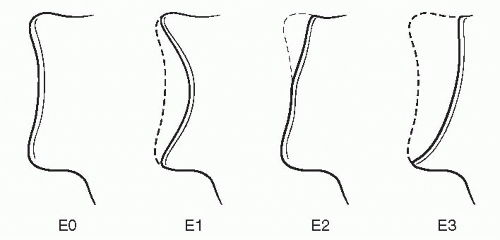

Several classification systems for rotator cuff deficient arthropathy are available.12,18 More relevant to glenoid bone loss in this setting is the classification set forth by Sirveaux et al.17 Three types of erosions were characterized: central erosions, erosions of the superior portion of the glenoid, and superior erosions which extended into the inferior portion of the glenoid. In their series of 77 patients, the majority (85%) of the patients had either normal glenoid morphology or a pattern of central erosions (Fig. 21-1). Out of 77 patients, only for 2 patients the glenoid bone grafting procedures were performed. They stressed the importance of placing the glenoid component on the inferior portion of the glenoid in order to minimize humeral contact with the glenoid in adduction, which can lead to notching. Also, attention to proper orientation of the glenoid baseplate so as to avoid superior tilt is also critical to stability of the construct.

Frankle et al. illustrated a classification system based upon commonly encountered morphological glenoid distortions.3 After reviewing 216 shoulders that underwent RSA, they concluded that the abnormal glenoid wear could be characterized into four subcategories: posteriorly, superiorly, globally, or anteriorly. Based upon the wear pattern, they found adjustments to the surgical technique may be necessary.

Other less common causes of substantial glenoid bone loss, such as post-traumatic arthritis or chronic instability, may be encountered. In situations of a chronic glenohumeral dislocation, truly massive glenoid bone loss may be encountered. Accounting for any substantial glenoid deficiency, to allow proper and durable fixation of the glenoid component is therefore crucial.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Evaluation of glenoid morphology starts preoperatively with plain radiography, which include a minimum of true anteroposterior (AP) (Grashey view) and axillary lateral views. Often, narrowing of the acromial-humeral interval (normally >6 mm) is demonstrated. Rounding of the humeral head and the greater tuberosity (femoralization) and concave erosive changes of the acromion and coracoacromial arch (acetabularization) are the radiographic representation of progressive changes of the arthropathy process.

Medial migration of the joint line, centrally or otherwise, will be grossly evident on plain radiographs but often require more advanced imaging such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Three-dimensional reconstructions using CT image data provides a global view of the glenoid and often reveals better the true extent of glenoid deficiency.3,5,10,15

Current glenoid designs for reverse shoulder prostheses utilize a variable set of peripheral fixation screws and a central peg or screw to provide fixation into the glenoid vault and body of the scapula. The assessment of the remaining glenoid vault is critical when planning for strategies for correction of any deficiencies.

The goal of glenoid component placement is to achieve rigid fixation of the baseplate in the correct orientation. Optimal placement of the glenoid component has been the subject of several investigations. Current recommendations include neutral or slightly inferior inclination and inferior placement on the face of the glenoid.4,9,11,13 Substantial glenoid erosions will cause the surgeon to evaluate whether reaming alone will allow achievement of these goals or if grafting of the defect will be necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree