Spinal tumors are classically grouped into 3 categories: extradural, intradural extramedullary, and intradural intramedullary. Spinal tumors may cause spinal cord compression and vascular compromise resulting in pain or neurologic compromise. They may also alter the architecture of the spinal column, resulting in spinal instability. Oncologic management of spinal tumors varies according to the stability of the spine, neurologic status, and presence of pain. Treatment options include surgical intervention, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and hormonal manipulation. When combined with this management, rehabilitation can serve to relieve symptoms, improve quality of life, enhance functional independence, and prevent further complications in patients.

Key points

- •

Spinal tumors are classically grouped into 3 categories: extradural tumors, intradural extramedullary, and intradural intramedullary tumors.

- •

Localized spine pain is the most common symptom in patients with epidural spinal cord compression at time of diagnosis.

- •

Motor weakness is the second most common symptom in patients with epidural spinal cord compression at time of diagnosis.

- •

Management of spinal tumors varies according to the stability of the spine, neurologic status, and pain. Treatment options include surgical intervention, radiation therapy, and systemic treatments, such as chemotherapy and hormonal therapy.

- •

Principles of neurorehabilitation applied to patients with traumatic spinal cord injury are equally appropriate for patients with spinal tumors.

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Spinal tumors are classically grouped into 3 categories: extradural tumors, intradural extramedullary tumors, and intradural intramedullary tumors ( Box 1 ).

Extradural spinal tumors

Primary malignant tumors

Lymphoma

Osteosarcoma

Ewing sarcoma

Chondrosarcoma

Chordoma

Sacrococcygeal teratoma

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

Solitary plasmacytoma

Fibrosarcoma

Primary benign tumors

Vertebral hemangioma

Giant cell tumor

Osteochondroma

Osteoid osteoma

Osteoblastoma

Sources of epidural metastases

Adult

Prostate cancer

Breast cancer

Lung cancer

Thyroid cancer

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Hodgkin disease

Multiple myeloma

Renal cell carcinoma

Colorectal cancers

Sarcoma

Germ cell tumor

Unknown primary

Pediatrics

Sarcoma: primarily Ewing sarcoma

Neuroblastoma

Germ cell tumors

Hodgkin disease

Intradural extramedullary tumors

Primary malignant tumors

Malignant nerve sheath tumors

Hemangiopericytoma

Primary benign tumors

Meningioma

Schwannoma

Neurofibroma

Paraganglioma

Ganglioneuroma

Sources of leptomeningeal disease

Glioblastoma

Central nervous system lymphoma

Leukemia

Lymphoma

Breast cancer

Lung cancer

Melanoma

Intradural intramedullary tumors

Primary tumors

Ependymoma

Myxopapillary ependymoma, subependymoma

Astrocytoma

Hemangioblastoma

Cavernous angioma

Neurocytic tumors

Oligodendroglioma

Embryonal neoplasm

Lipoma

Sources of intramedullary metastases

Lung cancer

Breast cancer

Melanoma

Lymphoma

Renal cell carcinoma

Extradural Tumors

Extradural (epidural) tumors refer to lesions outside of the dura mater, in the vertebral bodies, and neural arches. These tumors can be primary or secondary to metastatic disease and are more commonly malignant in nature. Primary extradural tumors arise from osteoblasts, chondrocytes, fibroblasts, and hematopoietic cells. Most extradural metastases occur through hematogenous spread. Direct extension of primary tumors may also lead to metastases in the spinal column. For example, prostate, bladder, and colorectal cancers may become locally aggressive and invade the lumbar or sacral epidural space.

Primary and metastatic lesions may be osteolytic, osteoblastic, or mixed. Osteolytic lesions are more common in adults and with breast, lung, and thyroid cancers. Osteoblastic lesions typically occur with prostate and bladder cancers and carcinoid tumors. Mixed lytic/blastic lesions can be seen with lung, breast, cervical, and ovarian cancers. Osteolytic lesions result in bone destruction greater than bone formation, whereas osteoblastic lesions result in bone deposition without breakdown of old bone first.

Both osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions alter normal bone architecture and can result in deformity or collapse of the affected vertebral body. This deformity can lead to spinal instability by increasing strain on the support elements of the spine, including muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules. It can also result in retropulsion of fractured bone fragments into the epidural space causing spinal cord compression.

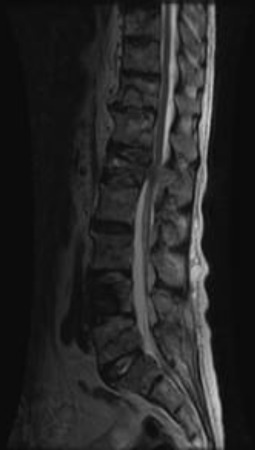

Extradural lesions ( Fig. 1 ) may grow into the epidural space resulting in spinal cord compression. Epidural spinal cord compression (ESCC) results in mechanical injury to axons and myelin. ESCC also results in vascular compromise of the spinal arteries and epidural venous plexus, leading to spinal cord ischemia and/or infarction.

Depending on the underlying malignancy, 2% to 5% of patients will develop clinical signs and symptoms of ESCC during the course of their disease. ESCC is most commonly diagnosed in thoracic lesions, though cadaveric studies have shown that the most common site of tumor burden in the spine is the lumbar region.

Intradural Extramedullary Tumors

Primary intradural extramedullary tumors are located within the dura mater but outside of the spinal cord parenchyma. These tumors arise from peripheral nerves, nerve sheaths, and sympathetic ganglion. They are most commonly benign. Extramedullary metastases ( Fig. 2 ), often referred to as leptomeningeal disease (LMD), are a relatively common complication of cancer, occurring in 3% to 8% of all patients. The most common site of involvement is the dorsal aspect of the spinal cord, particularly at the level of the cauda equina.

Metastatic disease is thought to reach the leptomeninges through hematogenous spread, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) seeding, and direct extension. CSF seeding can occur spontaneously or as a byproduct of surgical resection. Direct extension can occur along the epineurium or perineurium of spinal nerves or along veins exiting the vertebral body bone marrow.

Similar to extradural lesions, intradural extramedullary lesions can result in spinal cord compression and vascular compromise. Vascular compromise in this setting can result not only in ischemia but also in spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage. The risk of hemorrhage is greatest in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy.

Intradural Intramedullary Tumors

Primary intradural intramedullary tumors are located within the spinal cord parenchyma ( Fig. 3 ) and arise from glial cells, neuronal cells, and other connective tissue cells. These tumors account for 4% to 5% of all primary central nervous system tumors and are mostly benign. Intramedullary tumors are classified as low, intermediate, or high grade based on cytology. They can be found in any region of the spinal cord, although cervical and cervicothoracic segments are slightly more favored.

Intramedullary spinal cord metastases (ISCMs) are diagnosed in less than 1% of patients with cancer. Metastatic lesions reach the intramedullary space either by hematogenous spread or via direct extension along leptomeninges and nerve roots or through the Virchow-Robin spaces.

ISCMs usually occur in the setting of extensive metastatic disease and are rarely the first manifestation of systemic malignancy. Metastatic lesions can be seen throughout the spinal cord usually as a solitary lesion. The cervical spinal cord, a vascular-rich area, is the most common site of involvement.

It is generally thought that intramedullary lesions cause neurologic injury through direct compression of the surrounding spinal cord and vascular compromise.

Clinical manifestations

Extradural Tumors

Pain is the most common initial symptom in patients with ESCC (89%–90%) and may precede the development of other neurologic symptoms by weeks to months. Three classically defined types of pain in the setting of extradural involvement are local, mechanical, and radicular pain. An individual with epidural involvement may be affected by one or more of these pain types.

Localized pain is thought to be the result of periosteal stretching and inflammation caused by tumor growth. It is characterized as a deep gnawing or aching pain. It is often nocturnal and improves with activity and antiinflammatory medications.

Mechanical pain varies with position or activity, indicates impending or established spinal instability, and characteristically occurs with transitional movements or axial loading of the spine. This pain may also be elicited by lying prone or supine, particularly in the thoracic spine. Unlike localized pain, mechanical pain is often refractory to antiinflammatory agents. Mechanical pain responds well to stabilization of the spine with bracing or surgical fixation.

Radicular pain occurs in the setting of nerve root compression and is often described as sharp, shooting, or stabbing in nature. In the thoracic region, radicular pain is typically bilateral and described as a tight band around the chest or abdomen. In the cervical and lumbar regions, it is usually unilateral, radiating to the upper or lower extremity, respectively.

Motor weakness results from dysfunction of pathways that include the anterior horn cells and mediate movement. It is the second most common symptom of ESCC and is present in 35% to 85% of patients with metastases at the time of presentation. This weakness may be upper motor neuron, lower motor neuron, or a combination of both depending on the area of the cord involved.

Sensory impairments are usually present at the time of diagnosis (60%) in individuals with ESCC but are rarely the initial symptom. The pattern of impairment depends on the spinal pathway involved. Involvement of the lateral spinothalamic tract reduces pain and temperature perception on the contralateral side of the body, one or 2 dermatomes below the level of the lesion, but rarely causes paresthesias. Bilateral lesions may effect erection, ejaculation, and orgasm.

Dorsal column involvement results in loss of proprioception, vibration and touch from the ipsilateral body and information about visceral distension, and may result in paresthesias. Individuals may experience limb or gait ataxia as the result of their proprioceptive loss. Lhermitte phenomenon, an electric shock sensation that extends into the back and sometimes the limbs with changes in head or neck position, is frequently noted with dorsal column involvement in cervical and upper thoracic lesions.

Autonomic symptoms include bowel, bladder and sexual dysfunction, loss of sweating below the lesion and orthostatic hypotension. They are unusual as an initial symptom, but are often present at the time of diagnosis. Autonomic symptoms usually correlate with the degree of motor involvement.

Gait and truncal ataxia mimicking cerebellar involvement can be seen. This ataxia likely results from compression of the spinocerebellar tracts and can be differentiated from cerebellar lesions by the absence of dysarthria and nystagmus.

Unusual signs of ESCC include the eruption of herpetic zoster at the level of cord compression, Horner syndrome with C7 to T1 involvement and neuropathic facial pain with high cervical ESCC involving the descending fibers of the trigeminal-thalamic tract.

Intradural Extramedullary Tumors

Primary extradural tumors and LMD present in a similar fashion to ESCC but with a higher incidence of neurologic impairments. Approximately 70% to 90% of individuals will have pain as an initial symptom. This pain may be axial and/or radicular and worsened by recumbency. More than 60% of individuals undergoing surgical resection for LMD have some degree of weakness. Motor deficits may manifest in the absence of pain.

Almost all patients will have some degree of sensory involvement. Bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction have been noted in 30% to 80% of individuals with LMD, usually as an early finding. LMD may present with radiculopathy, neuropathy, or in a Brown-Séquard, conus medullaris, or cauda equina pattern.

Intramedullary Tumors

Intramedullary tumors may present with clinical manifestations surprisingly similar to epidural tumors. Pain, the most common initial symptom (30%–85%), may be described as radicular, posterior midline, dull, aching, and/or as paravertebral tightness and stiffness.

Neurologic deficits are common and usually involve cord segments below the level of the tumor. Overall, more than 92% of patients have some degree of motor deficit on examination. Sensory deficits are seen in 62% to 87% and bowel and/or bladder dysfunction in about 70% of patients.

The constellation of motor and sensory findings indicating Brown-Séquard syndrome is seen in 6% to 22% of patients. About 4% will have evidence of a Horner syndrome. Other patterns that can be seen in individuals with intramedullary tumors include central cord syndrome, conus medullaris syndrome, and cauda equina syndrome.

Spinal Instability

Spinal instability is defined as a loss of spinal integrity as a result of a neoplastic process that is associated with movement related pain, symptomatic and progressive deformity, and/or neurologic compromise under a normal physiologic load. Factors considered when evaluating the structural stability of the spinal column include location of the lesion ( Table 1 ), spinal alignment of the involved segment, extent of vertebral body involvement, involvement of posterior elements, bone lesion quality, overall bone mineral density, presence of multilevel contiguous and noncontiguous lesions, previous surgical intervention, cancer treatments such as radiation therapy and hormonal manipulation, degenerative changes, and presence of mechanical pain.