Lumbar Rehabilitation

Won Sung

Timothy J. Bayruns

Physical therapy has become a conservative standard of care for patients with low back pain. However, the evidence behind efficacy of physical therapy has been mixed. In the past, therapy has shown to be no more effective than an educational pamphlet.1 There is varying evidence for this treatment in general, with some studies suggesting good success from therapy, while others show no improvement at all. Part of the difficulty with the provision of services for patients with low back pain may stem from the challenge of correlating a specific pathology with the presence of pain.2,3 Further complicating the situation is that several therapeutic modalities are available in rehabilitation including exercise, manual therapeutic interventions, and physical therapeutic agents (heat, ice, ultrasound, electrical stimulation, etc.). Problems and poor outcomes occur when these many interventions are mismatched with the clinical presentation of the patient. To ensure that care is matched to the proper root problem, recent research has trended toward classifying patients to the correct treatment group.4,5,6

Three major treatment-based classification categories have been identified in the literature. These are trunk stabilization exercise, spinal manipulation, or direction-specific exercise groups to decrease pain and improve function. Inclusion or exclusion into these groups is based on the absence or presence of very specific examination findings, and the classification accuracy increases with the number of positive/negative findings. However, there are very important clues in a patient’s subjective reports that may help a physician determine patient membership to a particular treatment category, increasing likelihood of good outcomes. Often, the primary care physician is the first to encounter these patients. The ability to determine which treatment group a patient belongs to would help the physician offer appropriate advice to the patients until they are able to be seen by a rehabilitation specialist for further evaluation and treatment.

SPECIFIC EXERCISE GROUP (DIRECTIONAL PREFERENCE-FOCUSED EXERCISES)

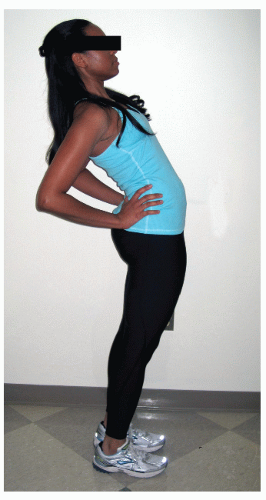

Treatment in this exercise group involves use of patient movement into very directionally specific movements of the lumbar spine to decrease pain. Typically, patients will report that there are specific movements that decrease their pain while others increase their pain.7,8,9,10,11 For example, a patient who reveals to the clinician that pain with sitting or bending increases pain while standing and/or walking (activities that involve lumbar extension) relieves or abolishes the pain demonstrates an extension-biased directional preference. These patients would benefit from activities as shown in Figures 73-1 and 73-2. Some patients may demonstrate a flexion bias, where bending and sitting improve their pain while walking and/or standing increases pain (most notable in patients with spondylitic stenosis). Performance of the exercises in Figures 73-3 and 73-4 may help these patients decrease their pain.

The role of the physical therapist in a patient with a directional preference is to capitalize on the directional preference to decrease pain, use manual therapeutic techniques to accelerate symptom reduction from directional preference if appropriate, and progress rehabilitation to facilitate functional outcomes. However, the primary care physician can play a crucial role in the first encounter with the patient by noting signs and symptoms associated with a directional preference. Advice can be offered to the patients by the physician to help decrease pain until they are able to be seen by a physical therapist.

FIGURE 73-1. Standing extension exercise typically used for patients with a bias toward extension of the lumbar spine relieving symptoms. Standing extension biased exercises can be practical as they can be performed in many situations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|