Lower Extremity Regional Musculoskeletal Syndromes: Hip, Knee, Ankle, and Foot

The range of regional disorders of the lower extremity, in the eyes of some observers, is as broad as the range for the upper extremity. Perhaps these observers are correct; myriad syndromes are said to account for the pain of the athlete, the elderly, or the average adult, each impugning “inflammation” of particular structures. Fortunately, many of these putative entities are private vocabularies of physical therapists, podiatrists, orthopedists, and so forth. I say fortunately because it allows me to offer discussions only of the terms that cross disciplines to reach primary care. As discussed for the upper extremity in Chapter 7, many of these diagnoses are exercises in inferential leaping that have begged systematic testing for generations. Some are worthy of study; others deserve obsolescence.

Unlike the proximal joints of the upper extremity, osteoarthritis (OA) targets hips and knees. OA generally spares the wrist and ankle, but targets the foot and hand in all of us to some degree and in a certain distribution. The hallmark in the foot is the bunion. We shall discuss OA in terms of its epidemiology and its potential to compromise joint integrity for each of these lower extremity targets. But this chapter gives us an opportunity to revisit two aspects of OA of particular relevance to students of occupational musculoskeletal disorders: the role of joint usage in its pathogenesis and the paradox of impressive OA in the absence of symptoms and vice versa.

There is a role for joint usage in the pathogenesis of OA of lower extremity joints1 just as there is for the hand (see Chapter 7). However, that role is neither necessary nor sufficient and probably minor. After all, those who develop OA of the hip are not the same people who develop OA of the knee; neither group develops OA of the ankle, and both groups develop bunions. Even on theoretic grounds, there is little reason to expect a major influence of normal usage on initiating OA or even facilitating progression. Realize that all the structures in and about the joint are dynamic, slowly being degraded and replaced with some periodicity over life. OA is best conceptualized as the disease that results from an aberrant physiology of repair. It has long been realized that the rate of progression of OA of the hands in women seems familial. On the basis of studies of identical British twins, it is clear that not only is the rate of progression of OA in the hands in women genetically programmed, so is the incidence of radiographically defined OA of the cervical and

lumbar spine2 and the knees3; more than half of the observed variability can be ascribed to a genetic influence. With the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in Finnish males, another study on twins came to a corollary conclusion for the lumbosacral spine; genetic influence overwhelms any discernible influence of usage.4 Furthermore, progression of lumbar spine disc degeneration correlates mainly with age, very little with body mass index (BMI), and not at all with physical activity.5 This implicates genetic factors as more determinative of the incidence and severity of spine, hand, and knee OA than any other known factor and leaves little room for these other factors to play much of a role. In particular, there is little room for occupational exposure to influence the incidence or progression of OA of the spine6 or the knee (vide infra).

lumbar spine2 and the knees3; more than half of the observed variability can be ascribed to a genetic influence. With the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in Finnish males, another study on twins came to a corollary conclusion for the lumbosacral spine; genetic influence overwhelms any discernible influence of usage.4 Furthermore, progression of lumbar spine disc degeneration correlates mainly with age, very little with body mass index (BMI), and not at all with physical activity.5 This implicates genetic factors as more determinative of the incidence and severity of spine, hand, and knee OA than any other known factor and leaves little room for these other factors to play much of a role. In particular, there is little room for occupational exposure to influence the incidence or progression of OA of the spine6 or the knee (vide infra).

As I pointed out some years ago, OA is far less prevalent than pain in the joints likely to be targeted by OA.7 Furthermore, many people with OA are asymptomatic, and many more with symptoms cope without seeking medical care. We shall explore what distinguishes the individual with symptomatic OA who seeks care with these other methods. Obviously, the challenge for such an individual relates to coping.8

HIP PAIN IN THE ADULT

Pain in the hip and buttock is a challenge for the diagnostician. A number of the axial syndromes discussed in Chapter 6 can present this way, as can vascular and visceral disorders. Furthermore, pain that can be ascribed to diseases of the hip need not be perceived as hip pain. The innervation of the hip joint derives from three nerves: the obturator, femoral, and sciatic. As a result, hip pain can refer medially, anteriorly, or posteriorly. It can also present or extend distally along the course of these nerves to the knee where hip pain can manifest as discomfort in the medial margin. Likewise, disease of the medial compartment of the knee can refer proximally to manifest as hip discomfort. Fortunately, the physical examination is exquisitely sensitive to disease of the hip, even more so than plane radiography. Therefore, a normal examination can exclude the hip as etiologic with considerable validity. An abnormal examination initiates a diagnostic algorithm that may well focus on hip pathoanatomy.

Anatomy

Only the shoulder exceeds the hip in range of motion. However, thanks to its ligamentous endowment, the hip is inherently stable; only the musculature stabilizes the shoulder. The femoral head is trapped in the acetabulum by the acetabular labrum. This fibrocartilaginous lip is completed inferiorly by the transverse ligament of the acetabulum. The articulation is enclosed by a thick, fibrous capsule encompassing the labrum, head, and femoral neck. In this way the femoral head is held tightly in the acetabulum so that weight bearing does not diminish the radiographic joint space (roughly equivalent to the thickness of the juxtaposed cartilage surfaces).

The ileofemoral ligament maintains contiguity when the hip is unloaded. In contrast, the radiographic joint spaces of both the knee and shoulder are diminished by compressive force implying less contiguity when the extremity is dependent. The extensive range of motion of the hip is limited by the surrounding ligaments and muscles: The hip flexors and the ileofemoral ligament limit extension to 20 to 30 degrees; the musculature limits hip flexion after the first 100 degrees or so, abduction after 70 degrees, and adduction after 25 to 30 degrees. Internal and external rotation are limited by the pubofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments, respectively; rotations increase in flexion where these ligaments relax.

The ileofemoral ligament maintains contiguity when the hip is unloaded. In contrast, the radiographic joint spaces of both the knee and shoulder are diminished by compressive force implying less contiguity when the extremity is dependent. The extensive range of motion of the hip is limited by the surrounding ligaments and muscles: The hip flexors and the ileofemoral ligament limit extension to 20 to 30 degrees; the musculature limits hip flexion after the first 100 degrees or so, abduction after 70 degrees, and adduction after 25 to 30 degrees. Internal and external rotation are limited by the pubofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments, respectively; rotations increase in flexion where these ligaments relax.

Physical Examination

There is a wealth of insight that is forthcoming from observing the posturing and gait of any patient with musculoskeletal symptomatology. With axial and lower extremity symptoms, this is mandatory. Patients with hip disease as the cause of their hip pain have an antalgic gait; they move slowly on the asymptomatic side and shorten the stance phase on the symptomatic side. Furthermore, internal rotation in extension is the arc most likely to be compromised by any intra-articular disease of the hip. Because internal rotation in extension is necessary to swing one’s pelvis about the pivot provided by the weight-bearing hip, hip disease provokes a gait rendered less flowing by the need to hold the pelvis fixed on the compromised pivoting hip. If extension is compromised as well, the swing and forward thrust of the pelvis are further abbreviated. Increasing flexion contractures leads to compensatory posturing at the low back and knee in an attempt to maintain balance but at a price of further compromise in biomechanical stability. The experienced clinician can often spot severe hip disease as the patient walks into the office.

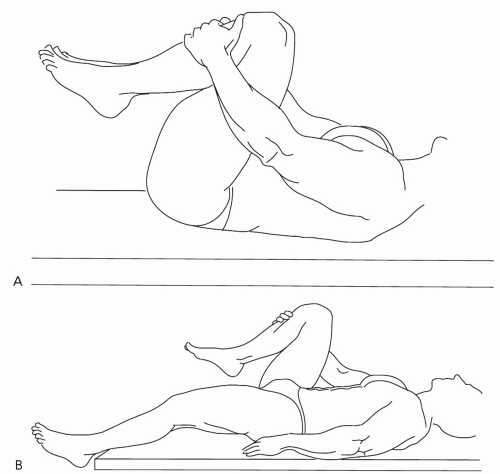

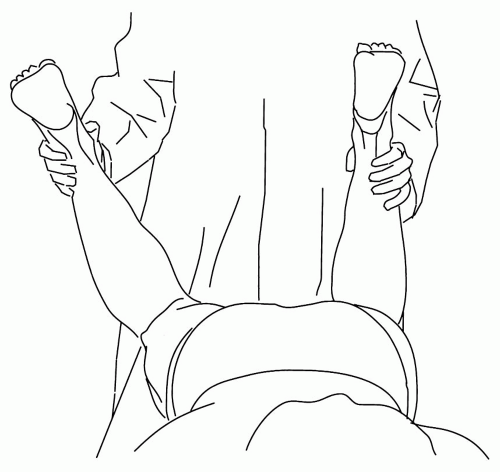

Destruction of the femoral head can lead to true leg length discrepancies. However, minor asymmetry, as much as 1 to 2 cm, is a normal variant with neither diagnostic specificity nor prognostic import. In fact, a leg length discrepancy of more than 5% is required before any alteration in the biomechanics of gait is detectable.9 Effusions of the hip cannot be detected on examination. Palpation has little localizing value; focal tenderness is nonspecific. However, determination of range of motion is exceedingly valuable. Figures 8.1 and 8.2 illustrate this portion of the examination. Normal, symmetric, pain-free arcs of motion, particularly in rotation, exclude intra-articular disease of the hip as an explanation for the hip pain, and the diagnostic evaluation is redirected (Table 8.1). Compromise in motion is not totally specific; psoas irritation can be provoked with internal rotation in extension, and femoral and sciatic stretch signs can confound this examination (although with care such stretching is avoidable in discerning hip motion, as illustrated in Fig. 8.2). With such provisos, compromised range of motion strongly suggests intra-articular disease.

Bursitis

There are at least 18 bursae in the region of the hip. Ascribing hip pain to “bursitis” is a venerable assertion. Of all these bursae, three are said to be causes of localized

tenderness: the ischiogluteal, iliopectineal, and trochanteric. Ischiogluteal bursitis is supposed to be the cause of “weaver’s bottom,” diagnosed because there is tenderness over the ischial prominence. However, as is true for all these bursitides, frank inflammation is not a feature. Furthermore, “weaver’s bottom” is rarely diagnosed today and not because there are no longer sedentary weavers. Even cyclists are spared. Perhaps that is because contemporary diagnosticians are more likely to be impressed that the tenderness is near the sciatic notch and ascribe the discomfort to sciatica rather than bursitis. In any event, attention to posture usually is palliative.

tenderness: the ischiogluteal, iliopectineal, and trochanteric. Ischiogluteal bursitis is supposed to be the cause of “weaver’s bottom,” diagnosed because there is tenderness over the ischial prominence. However, as is true for all these bursitides, frank inflammation is not a feature. Furthermore, “weaver’s bottom” is rarely diagnosed today and not because there are no longer sedentary weavers. Even cyclists are spared. Perhaps that is because contemporary diagnosticians are more likely to be impressed that the tenderness is near the sciatic notch and ascribe the discomfort to sciatica rather than bursitis. In any event, attention to posture usually is palliative.

The trochanteric bursa lies between the tendon of the gluteus maximus and the posterolateral prominence of the greater trochanter. Trochanteric bursitis is a common label affixed to hip region pain when there is tenderness near the greater trochanter. Usually the tenderness is restricted to a point that is posterior and superior to the trochanter, quite distant from the location of the bursa, which is 3 to 4 cm deep to the skin posterolateral to the trochanter. Injecting the tender tissue with local anesthetic and corticosteroid is common practice and associated with transient relief. However, transient benefit from empiric injection therapy is far from convincing support of the pathogenetic inference; such experimental support is long overdue. MRI has documented gluteal tears in some patients with this presentation.10 As we have learned from other examples of regional musculoskeletal illness, many regional diseases, such as subtle radiculopathies, can present in this fashion requiring only explanations and patience and not multiple injections and trials of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs.

TABLE 8.1. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF REFERRED “HIP” PAIN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

My skepticism heightens for the concept of iliopectineal bursitis. This bursa is contiguous with the capsule of the hip and separates the iliopsoas muscle from the iliopectineal eminence. It occasionally communicates with the synovial cavity of the hip. Because it lies medially in Scarpa’s triangle, it is said to cause pain in the anterior pelvis, groin, and thigh, exacerbated with movement. However, the diagnosis eludes all contemporary modalities for confirmation, and the number of viable competing explanations remains overwhelming. Iliopectineal bursitis is a heuristic label, as may be many of the regional musculoskeletal illnesses ascribed to “bursitis.”

Intra-articular and Periarticular Diseases of the Hip

OA is the most common disease of the hip but not the most likely explanation for most hip pain. Approximately 10% of the adult Dutch population believe they have hip OA,11 but only 0.1% are likely to have radiographically demonstrable important hip OA (vide infra), and not all of those will be aware of it. Thus, when a patient presents with a chief complaint of hip pain, there is a differential diagnosis.

Infection

Most individuals with septic hip or osteomyelitis of the femur or pelvis will not be misdiagnosed with a regional disease. Fever, pain at rest, or pain at night will provide compelling clues to direct the diagnostician to appropriate imaging studies and diagnostic aspirations. There is a pitfall in that all these infections can be quite insidious in onset and progression. This is particularly true for tuberculous arthritis. Any systemic symptom or suggestion of night or rest pain should place the diagnostician on guard.

Primary Neoplasms of the Hip Joint

There are primary tumors of the synovium and metaplastic conditions such as pigmented villonodular synovitis. These present with the picture of arthritis with pain and restriction on motion. The diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion; usually there is a degree of destruction on plane radiographs and increased activity on scintiscanning. Pigmented villonodular synovitis is suspected when synovialis

reveals bloody fluid and synovial biopsy documents infiltration with hemosiderinladen macrophages. Fortunately, primary tumors and pigmented villonodular synovitis are rare lesions and particularly rare at the hip; more accessible joints such as the knee are targeted. It is also true that cancer rarely metastasizes to any synovial bed; an observation that suggests insights into the pathogenesis of metastasis that still elude investigators. In fact, of all neoplasias, only lymphoproliferative diseases, multiple myeloma, and leukemia (particularly in childhood) infiltrate the synovium with any regularity. Although intra-articular neoplasms are not much of a worry, periarticular neoplasms are an important consideration.

reveals bloody fluid and synovial biopsy documents infiltration with hemosiderinladen macrophages. Fortunately, primary tumors and pigmented villonodular synovitis are rare lesions and particularly rare at the hip; more accessible joints such as the knee are targeted. It is also true that cancer rarely metastasizes to any synovial bed; an observation that suggests insights into the pathogenesis of metastasis that still elude investigators. In fact, of all neoplasias, only lymphoproliferative diseases, multiple myeloma, and leukemia (particularly in childhood) infiltrate the synovium with any regularity. Although intra-articular neoplasms are not much of a worry, periarticular neoplasms are an important consideration.

Malignant primary bone tumors about the hip are rare in the adult. Chondrosarcoma has a predilection for the femur and pelvis and a peak incidence in the fifth and sixth decades. Giant cell tumors usually present in the third or fourth decades with a propensity for the end of a long bone. Ewing’s sarcoma also has a predilection for the femur and occurs even earlier. With all these primary tumors, the presenting symptom is pain in the region of the lesion often with nocturnal exacerbation. Each produces radiographically discernible bony destruction and can lead to pathologic fractures. However, past midlife, primary tumors are far less frequent than metastatic lesions to the hip and pelvis. Again, the clue is pain that is prominent at rest and at night. Imaging techniques are localizing, and biopsy is diagnostic.

Osteoid osteoma is a benign focus of dysplasia consisting of an osteoid nidus surrounded by an osteosclerotic zone. The lesion is unifocal and can occur throughout the appendicular skeleton. However, 20% of osteoid osteomas occur in the proximal femur, and another 10% occur in the pelvis. The typical patient presents in the second decade of life, although the onset of symptoms in the third and even fourth decade is well described. The symptoms are characteristic: dull aching pain prominent at rest and at night and relieved by activity or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), usually aspirin. With hip region involvement there may be an antalgic gait but rarely signs of intra-articular inflammation. The osteoma can often be discerned on plane radiographs as a small round lesion with a lucent center. It is hypervascular and therefore readily detected by scintography. Surgical perturbation is a reasonable option with persistent or severe symptoms; however, the natural history is one of spontaneous regression of symptoms after 4 to 6 years of illness.

Transient Osteoporosis of the Hip

This is a form of reflex sympathetic dystrophy (see Chapter 9). Involvement of the shoulder is far more frequent, but the symptoms are similar regardless of the region targeted. The patient describes diabolically pervasive aching pain, prominent at rest and at night, with progressive restriction in motion. At the hip, there are few signs on examination other than restriction in motion, including rotation in extension (Fig. 8.2). As the disease progresses, the femoral head appears osteopenic on radiographs. However, even before such radiographic findings, the femoral head and even the entire proximal femur manifest their increased metabolic activity as a bone

scan with positive results or an MRI with abnormal results. Bone radiologists assure me they can distinguish the MRI of transient osteoporosis from that of osteonecrosis, although they are relying on subtleties that have yet to be tested for reliability. This is not a minor issue because transient osteoporosis is self-limited, and if such patients are included in the studies of intervention for osteonecrosis, they will bias the outcomes toward the favorable.

scan with positive results or an MRI with abnormal results. Bone radiologists assure me they can distinguish the MRI of transient osteoporosis from that of osteonecrosis, although they are relying on subtleties that have yet to be tested for reliability. This is not a minor issue because transient osteoporosis is self-limited, and if such patients are included in the studies of intervention for osteonecrosis, they will bias the outcomes toward the favorable.

Osteonecrosis

Osteonecrosis, also termed aseptic or avascular necrosis (AVN), is far more common in the lower extremity and particularly at the femoral head. The primary cause is often unclear; there must be a factor that predisposes to a compromise in the maintenance of the structural integrity of the subchondral bone of the femoral head. Microfracturing leads to progressive collapse with ineffective repair.12 In all likelihood, judging from the clinical settings in which AVN is most prevalent (Table 8.2), the initiating factors are diverse, although there may be a final common pathway to collapse of the femoral head and secondary OA of the hip. For example, fracture of the neck of the femur can directly compromise blood supply to the head. However, the explanation for systemic lupus erythematosus or hypercorticism is less facile. Even the association with exogenous steroid exposure, although compelling, speaks to a rare and idiosyncratic side effect.13 There are recent data indicating that subtle thrombogenic genetic defects such as Factor V Leiden may have a predisposing role.14 Consistent with the notion of a primary thrombotic event, there is some suggestion of venous hypertension in the femoral neck. The theory and the observation have unleashed surgical assaults on the femoral neck adding “core decompression” or the grafting of vascularized fibula to the traditional menu15 in hopes of halting what is otherwise inexorable progression. However, the experience with this procedure is far from uniform, suggesting that the theory is flawed or that there are alternative explanations in some cases, such as transient osteoporosis

of the hip. The symptoms of AVN are pain at rest and with weight bearing accompanied by signs on examination of intra-articular inflammation. Early on, plane radiograph results are normal; one must resort to scintiscanning, or more definitively, to MRI, for diagnosis. Once the femoral head has started to collapse, the course, despite staccato symptoms, is inexorably toward total hip replacement.16

of the hip. The symptoms of AVN are pain at rest and with weight bearing accompanied by signs on examination of intra-articular inflammation. Early on, plane radiograph results are normal; one must resort to scintiscanning, or more definitively, to MRI, for diagnosis. Once the femoral head has started to collapse, the course, despite staccato symptoms, is inexorably toward total hip replacement.16

TABLE 8.2. CLINICAL SETTINGS IN WHICH AVASCULAR NECROSIS OF BONE IS MOST PREVALENT | |

|---|---|

|

Osteoarthritis of the Hip

OA is the major intra-articular disease of the hip in the adult. By age 80 years, some 2% of Americans will have severe OA of a hip. Another 2% will have less severe involvement. These are small but impressive numbers. However, they pale in comparison with the number of Americans who experience pain in the hip region in any given month. The distinction between pathology in a musculoskeletal region (the disease) and symptoms in the same region (the illness) is critical to understanding all regional musculoskeletal disorders. The discordance between disease and illness is far more striking than concordance.17 For example, more than 40% of the individuals whose hip OA was detected radiographically in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I could recall no relevant symptoms in the previous month. A similar degree of sensitivity to illness pertains to physical signs on examination. This concept of disease-illness discordance will be further developed shortly when we consider knee pain. Here we will focus on the hip joint and its disease.

OA is generally defined by its pathoanatomic hallmarks as demonstrated on radiographs. For the clinician, the diagnosis conjures up an image of compromised joint motion and an ill-conceived assumption that if there are radiographic abnormalities there will be associated symptoms. Defining the limits of normal, including radiographic limits, is difficult. Osteophytes are the more readily discernible, even quantifiable, radiographic feature. But as with the axial skeleton (Chapter 6), they are so common about the hip that their absence in the elderly is abnormal. In addition, they correlate least well with symptoms. Even at the hip, grading the magnitude of established disease is difficult; it is only with intense training that interobserver reliability reaches 50% for the earliest changes. That is because of the wide variation in the width of the normal joint space and in the willingness to label irregularities of bone at the joint margin as osteophytes.

The normal hip joint is incongruous; with weight bearing, a lateral rim of the cartilage of the femoral head is brought into contact with a restricted weight-bearing region of acetabular dome. The weight-bearing cartilage is thicker with sparser chondrocytes. With aging, the joint becomes more congruous, bringing the more atrophic cartilage into contact and accounting for the difference in angulation. In the past, this alteration in femoral head tilt has been held to be pathogenetic for OA, but it is more likely a benign consequence of aging. In progressive OA, two-thirds of hips demonstrate progressive loss of cartilage in a superolateral direction accompanied by progressive osteophytosis generally from the medial wall. The remaining one-third of hips with OA demonstrate medial or even concentric migration. However, this pattern is less specific for OA and should raise the possibility,

albeit remote, of Paget’s disease in the case of medial migration and systemic rheumatic disease, including the spondyloarthropathies in the case of concentric or axial migration.

albeit remote, of Paget’s disease in the case of medial migration and systemic rheumatic disease, including the spondyloarthropathies in the case of concentric or axial migration.

OA is the process of loss of articulating cartilage accompanied by ineffective repair by the remaining cartilage and adjacent bone. The dominant theory pivots on biomechanical insult. Sheering forces interrupt the collagen network such that the articular cartilage loses the ability to restrain the swelling pressure of the glycosaminoglycans and imbibes water. This swollen cartilage seems further vulnerable to disruption by sheering forces. The pathogenesis of OA of the hip calls this theory into question. The association of progression of hip OA with aging is inconsistent, and there is no association with angulation of the femoral neck, weight, or BMI.18

There is an alternative hypothesis based on the fact that cartilage biology is highly dynamic. After all, cartilage is a living tissue with turnover rates measured in weeks. One could argue that OA is a disease of ineffective repair rather than biomechanical insult. This perspective suggests that influences that support connective tissue repair, such as repetitive motion, would retard the process. It also suggests that OA might be a target for pharmacologic reversal rather than interventional resignation until it is time for salvage. For now, clinicians have little to offer than to document the progressive loss of cartilage, the reactive formation of bony spurs (osteophytes), which are cartilage covered and form at the joint margins, and the degradation of the elegant subchondral bony plate into an irregular coarse structure riddled with cysts. Such is OA, a sclerotic damaged joint whose only redeeming feature is a diminished likelihood of fracture.19

Fortunately, and inexplicably, OA targets very few joints in an individual. There is some tendency to symmetry, but little to multifocality. Patients with OA of the hip are no more likely to have OA of any other joint than sex- and age-matched individuals whose hips are spared. Furthermore, obesity does not predispose to hip OA. There are some data to the contrary, but such are neither impressive nor reproducible. The inferences that derive from these observations have important ramifications regarding the pathogenesis of OA in general and of the hip in particular: Usage cannot be a primary or even major precipitating influence. Otherwise the same individual whose hip is afflicted should have the knee at risk, and this is not the case. Furthermore, with or without OA of the hip or knee, the ankle is always spared. Such considerations would seem to suggest that factors other than usage or obesity must be primary influences. There is epidemiologic literature testing this hypothesis for OA of the hip that contrasts significantly with the parallel literature for OA of the knee (vide infra):

Influence of Sporting Activities on the Development of Hip OA. This extensive literature has been the subject of a recent systematic review.20 There are several thousand articles, nearly all of which are anecdotal and therefore provide insights that are too uncertain in validity to sway our thinking (see Chapter 10). Only 22 systematic studies are believed to be useful in that regard, although most were seriously flawed in design or data analysis. There is only one cohort study: Women who were committed joggers and who participated in follow-up studies

for nearly a decade were no worse for the wear.21 The other studies were case-control, in which the “cases” were current or former athletes, ballerinas, or patients requiring total hip replacement. The diagnosis of hip OA was usually based on clinical criteria, sometimes exclusively on radiographic criteria. No study discerned a hazard of any sporting activity for radiographic disease. No hazard was discerned on clinical grounds in the majority of the studies, and very little hazard was discerned in the few studies that discerned any. All these case-control studies are at risk for “survivor bias,” that is, the likelihood that the individuals who had hip OA had long ago dropped out of the population being studied, enriching the population of people with healthy hips. Of course, the literature itself is at risk for “publication bias,” that is, the greater likelihood for positive studies to be submitted and accepted for publication than negative studies. Given the reassuring cohort study, the absence of any association with radiographic hip OA, and the inconsistent and marginal association with clinical hip disease, I would be unwilling to cast aspersions on running, soccer, ballet, or any other similar activity.

Influence of Occupational Lifting and other Physical Demands of Work on Hip OA. Epidemiologic studies of the influence of occupation are more difficult to design than studies of athletes. Athletics demand some stereotypic activities that can be predominant usages, particularly in elite athletes. However, lower extremity usage in the workplace is seldom so stereotypic or that different from usages outside work. Take, for example, a recent case-control study from Cheshire in the United Kingdom.22 All adults who were registered in two general practices received a postal survey. Approximately 3500 responded about whether they had experienced 1 day of hip pain in the previous month and about their perception of the physical demands of their occupational and leisure activities. The 10% of adults who had experienced hip pain were the “cases,” and the other adults were the “controls.” Younger men were more often selected to be the cases. After controlling for gender and age, the authors found that the data impugned prolonged sitting at work and prolonged walking in sports as hazards for the experience of hip pain. Even the authors were cautious in interpreting these data, although they seem willing to accept that there was some influence of usage on hip pain. I would be even more cautious because “hip pain” can be a self-limited experience that has nothing to do with OA. A systematic review23 identified 16 articles of sufficient methodologic quality to be informative regarding the influence of occupational usage on hip OA. Most of these studies were from Northern Europe. In all, the diagnosis was clinical, often either radiographic or because the patients had undergone or were awaiting total hip replacement. The assessment of physical workload was usually based on an interview or a questionnaire; seldom was leisure activity considered. Seven of the case-control studies compared “farming” with no farming or light physical workloads as the exposure. Another six compared “heavy lifting” with lesser perceived exposures. Nearly all case-control studies discerned a hazard from “farming” or “heavy lifting.” The odds ratios were more marginal in the two retrospective open-population cohort studies than in most case-control studies; no hazard was discerned for women, and the odds

ratio was approximately 2.5 for men. The authors of this systematic review were willing to conclude that the evidence for an association between hip OA and occupational exposure was “moderate” at best. I would suggest that the hazard is not in the development of hip OA or even of symptomatic hip OA. Rather, people faced with unavoidable physical demands are more likely to complain of their symptomatic hip OA. “Survivor bias” is less likely to rescue farmers and heavy laborers than athletes.

The philosophy of management for OA of the hip has been different than that for OA elsewhere ever since the advent of the total hip replacement. Total hip replacement is an extraordinary advance, certainly assuming a place of honor in the pantheon of 20th-century advances. In the hands of an accomplished surgeon, the patient with regional hip disease who is otherwise well has every reason to anticipate pain-free ambulation with a normal gait within 1 month of surgery. In some 85%, this good result persists for 20 years or more. Total hip replacement is a reasonable24 and cost-effective25 option for anyone with chronic discomfort and significant functional compromise from OA. No other joint has yielded to the onslaught of reconstructive surgery in such a gratifying fashion. This probably reflects the inherent stability of the normal hip and its prosthetic replacements; other joints depend to a greater extent on extra-articular supporting structures for stability and function. Because the outcome is so favorable, appropriate advice is more demanding of the wisdom of the physician and the quality of the patient-doctor rapport. Total hip replacement is an elective procedure that should be postponed until the risk/benefit ratio becomes compelling. Even if the risk is only 1 in 1000, the physician should have exercised sufficient forethought to be able to look the patient or the patient’s family in the eye should catastrophe eventuate. In addition, there is risk for less catastrophic postoperative complications measurable as a few percent, including nonfatal pulmonary embolism, wound site infections, and failed prostheses. Finally, although it is a dramatic advance, total hip replacement has a finite life expectancy; if avocations and vocations that call for a great deal of weight bearing are avoided, the need for replacement of the prosthesis is probably postponed. More than one patient tolerates crutch walking rather than assume the risks; others seek the surgical solution early on.

The management of the patient with hip OA is a process of compromise until the specters of postoperative catastrophe, albeit remote, and long-term complications become tolerable. Realize that symptoms can waver and that the course is unpredictable; in terms of symptoms and function, the majority with modest OA manifest little tendency toward progression. For some, the pain is staccato with prolonged intercritical periods. The path to the decision for total hip replacement is not one of benign neglect. It is important that thigh musculature be maintained for optimal function during the years of conservative management and for optimal postoperative function. Exercise regimens with little weight bearing should be emphasized (even after a total hip replacement): cycling, swimming, quadriceps setting, and so forth. Although there are reservations (Chapter 5), NSAIDs are traditionally offered in this setting. The patients tend to be younger than patients with knee

pain in the setting of knee OA. Perhaps that is why drug toxicity is not as associated with treatment of hip pain as much as with treatment of knee pain. Nonetheless, to extrapolate from the experience with knee pain,26 a trial of acetaminophen for managing symptomatic episodes in the setting of OA is advisable.

pain in the setting of knee OA. Perhaps that is why drug toxicity is not as associated with treatment of hip pain as much as with treatment of knee pain. Nonetheless, to extrapolate from the experience with knee pain,26 a trial of acetaminophen for managing symptomatic episodes in the setting of OA is advisable.

KNEE PAIN

Knee pain is remarkably common. According to a household survey, 10% of Americans recall at least 1 month of significant daily knee pain each year. In the United Kingdom, the prevalence after age 50 years approaches 50%, in half of whom the morbidity is persistent.27 The individual who feels compelled to seek medical attention should be greeted with diagnostic wariness. After all, seldom is this the individual’s first experience with knee pain; something about its quality or duration has precipitated the choice to be a patient. Fortunately, because the knee is so accessible, most diagnostic uncertainty can be dispelled with a thorough initial history and physical examination. Clues to systemic disease and arthritis elsewhere are sought. Then the painful knee is examined closely. Overt inflammation, whether from trauma, some form of synovitis (including infected or crystal induced), or hemarthrosis, is usually obvious; there may be warmth, even erythema, obvious effusion, and spontaneous posturing in 30 degrees of flexion to diminish intra-articular pressure. However, it behooves the clinician to learn to identify subtle inflammation of the knee. It is possible to detect small synovial effusions if one learns to elicit a “bulge sign,” and larger effusions render the patella ballotable (Fig. 8.3). One can demonstrate a bulge sign in some asymptomatic knees, for example, in as many as 10% of women beyond midlife who are overweight. However, the bulge sign in the symptomatic patient leads to one of the most useful diagnostic maneuvers in clinical medicine—the diagnostic arthrocentesis. Clinicians should be accomplished in aspirating several milliliters of fluid for synovialis. Synovialis offers a wealth of diagnostic information (Table 8.3).

The patient who has mechanical knee pain without effusion or with a noninflammatory effusion has regional knee pain. This knee pain is discordant from radiographic abnormalities of the knee. This holds even in the seventh decade, but it is the rule earlier in life. Ascribing knee pain to pathoanatomic aberrations in and about the knee is a tenuous exercise.5 However, it is the traditional exercise and contains some nubbins of truth.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree