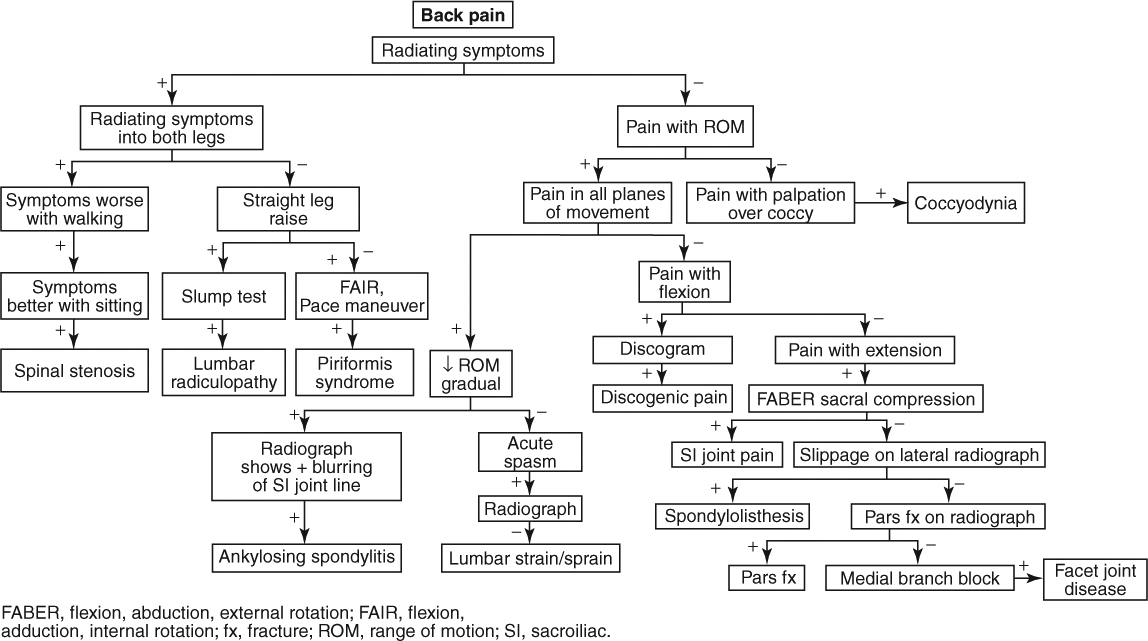

Lower Back and Shooting Leg Pain

|

Red Flag Signs and Symptoms

Any of these signs and symptoms should prompt urgent evaluation and appropriate intervention:

Fevers

Chills

Recent unintended weight loss

Progressive neurologic symptoms

Change in bowel or bladder function

Significant trauma precipitating symptoms

LUMBAR STRAIN/SPRAIN

Background

In much the same way that the mast of a sailboat relies on its supporting standing riggings, the spine relies on all of its supporting muscles and ligaments to maintain its stability. All of these muscles and ligaments can be strained (muscles) and sprained (ligaments). When muscles are imbalanced, weak, or tight, they are more likely to place abnormal biomechanics on the spine and result in acute injury.

Lumbar strain/sprain is probably the most common injury to the lower back. Around 90% of the population at some point in their life has back pain, and >90% of the time the pain resolves on its own without medical intervention. Most of these cases are ascribed to strain/sprain. It is not possible to know if this attribution is accurate. It may be that when a person suffers an acute lower back pain, it is related to the disc. It may be caused by something else

such as a sprain/strain. Because it almost always resolves on its own, aggressive diagnosis is not generally indicated in the acute period.

such as a sprain/strain. Because it almost always resolves on its own, aggressive diagnosis is not generally indicated in the acute period.

Clinical Presentation

Patients typically recall an inciting event in which they twisted or strained to lift a heavy load that immediately precipitated pain in the lower back. Sometimes, the pain subsides only to worsen at night and then again in the morning. Other times, there is no inciting event and the patient simply wakes up in the morning and describes a pain in the lower back. The pain is usually moderate but may become severe. Most patients wait a few days or more before coming to the doctor. The pain does not radiate and is not associated with any numbness, tingling, or weakness. Sometimes, the pain does refer to the buttocks. When this happens, it refers in a vague, achy pattern. Patients also may report stiffness in the lower back. The pain can be unilateral or bilateral. If the pain has lasted >2 to 3 weeks, it is unlikely to be a simple strain/sprain.

Physical Examination

On examination, the patient may have stiffness in the lower back and be hesitant with movements involving trunk flexion and/or extension. Lumbar lordosis is usually lost because of muscle spasm. Tenderness is typically elicited over the involved area. The muscle is tight, and sometimes a trigger point can be palpated. Trigger points are distinguished from tender points because the former create a referral pain pattern on palpation (tender points are only tender at the exact site of palpation).

Neurologically the patient is intact. Range of motion is intact but hamstrings and hip flexors are often found to be tight.

Diagnostic Studies

Treatment

Reassurance that the pain will most likely go away soon is a large part of initial treatment. Ice and NSAIDs can help in the acute period. In addition, patients should be educated about their backs and how they can take steps to protect their back in the future. An episode of back pain in the past is a predictor of future back pain. Muscle imbalances should be sought and addressed. A brief course of physical therapy is a very good idea for patients. It may speed recovery and it will also teach patients a home exercise program (HEP). The HEP incorporates lumbar stabilization, stretching, and strengthening and is important for the patients to make a part of their daily routine to help them avoid back problems in the future.

Doctors used to recommend absolute bed rest for patients with back pain. Today, this is not the standard of care. Patients should not do activities that exacerbate pain. However, maintaining flexibility and activity is critical to help nourish the structures in the back, speed recovery, and prevent stiffness and further deterioration.

LUMBOSACRAL RADICULITIS/RADICULOPATHY

Background

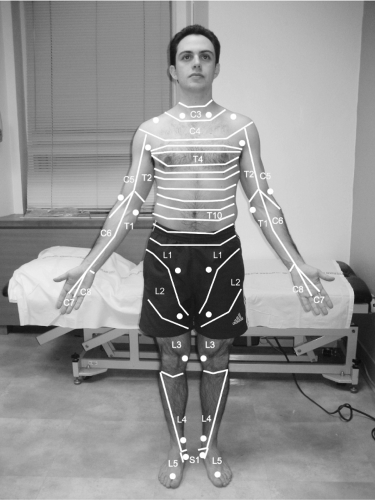

Although nowhere near as common as lower back pain, lumbosacral radiculitis is a relatively common problem affecting about 1% of the population. Radiculitis is characterized by inflammation of the nerve root or compression of the dorsal root ganglion. Symptoms include shooting electric pain that radiates down from the lower back and/or buttock into the lower extremity. Patients can often take two fingers and trace the distribution of their pain. This is opposed to other referral pain patterns

where the pain may be diffuse, vaguely localized, and achy. The symptoms generally follow a characteristic sclerotomal distribution along the nerve root (Fig. 5.1). Lumbosacral radiculopathy is characterized by loss: loss of strength, loss of sensation, and/or loss of reflex within the distribution of the involved nerve root(s). Because lumbosacral radiculopathy and radiculitis often coexist and because they are treated the same way, they are often considered as one disorder.

where the pain may be diffuse, vaguely localized, and achy. The symptoms generally follow a characteristic sclerotomal distribution along the nerve root (Fig. 5.1). Lumbosacral radiculopathy is characterized by loss: loss of strength, loss of sensation, and/or loss of reflex within the distribution of the involved nerve root(s). Because lumbosacral radiculopathy and radiculitis often coexist and because they are treated the same way, they are often considered as one disorder.

Note that in the rare instance that neurologic symptoms of a lumbosacral radiculopathy become severe and progressive, or if patients have a sudden change in their bowel or bladder habits (including losing continence), emergent care is necessary and the patient should know to go to the emergency department. Cauda equina syndrome, in which the cauda equina is compressed, may result and is a surgical emergency.

Clinical Presentation

Patients typically present with dull back pain and shooting electric pain that radiates into their lower extremity in a characteristic distribution. Patients sometimes complain of mild weakness (Table 5.1) and/or numbness in their lower extremity. The pain may have come on acutely or developed gradually. Pain may be exacerbated by bending over (in which case a protruded disc is implicated as the cause)

or with extension (in which case facet hypertrophy is more likely to be the cause). The shooting pains often are intermittent and worse with certain movements.

or with extension (in which case facet hypertrophy is more likely to be the cause). The shooting pains often are intermittent and worse with certain movements.

TABLE 5.1 LUMBOSACRAL DISTRIBUTION OF SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Physical Examination

Patients may have increased symptoms with lumbar flexion or extension. Straight leg raise (Fig. 5.2) is often positive. In this test the patient lies in the supine position

and the physician slowly raises the extended leg into the air. Reproduction of radicular symptoms (not hamstring tightness or achy back pain) is a positive test. Passively extending the ankle while the leg is raised may exacerbate symptoms and is highly suggestive of radicular origin.

and the physician slowly raises the extended leg into the air. Reproduction of radicular symptoms (not hamstring tightness or achy back pain) is a positive test. Passively extending the ankle while the leg is raised may exacerbate symptoms and is highly suggestive of radicular origin.

Seated slump test (Fig. 5.3) is also often positive. In this test, the patient is seated and instructed to drop the chin to the chest and “slump forward.” The examiner then passively extends a leg and foot, placing a stress

similar to the straight leg raise. Reproduction of symptoms is a positive test.

similar to the straight leg raise. Reproduction of symptoms is a positive test.

Patients may also be found to have numbness and/or weakness along the nerve root(s) that are implicated. Reflexes may be hyporeflexic (Table 5.1).

If an L5 radiculopathy is present, and the patient has a weak gluteus medius, the patient may have a positive Trendelenburg test. In this test, the patient stands on one leg. If the gluteus medius is weak, the patient lurches to that side (Figs. 5.4A and B).

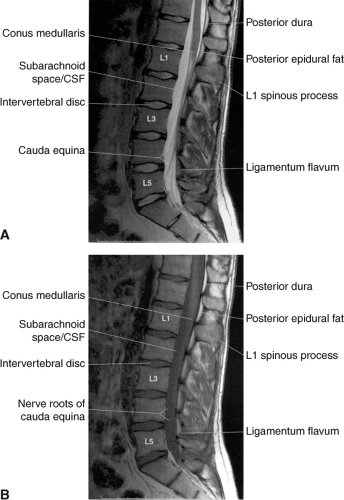

Diagnostic Studies

Radiographs may be obtained and may reveal facet arthropathy, disc space narrowing, or other degenerative changes.

If symptoms are severe, constant, chronic, and/or epidural injections are being considered, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be obtained (Fig. 5.5). The MRI helps delineate the site of nerve root involvement; it helps rule out other pathologies, and it guides injection site.

Treatment

The cornerstone of treatment is physical therapy that focuses on lumbar stabilization, increasing hamstring and hip flexor flexibility and strength, and improving postural biomechanics.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesics, and muscle relaxants can be helpful depending on the severity of the symptoms. Nerve-stabilizing medications such as gabapentin (e.g., Neurontin) and pregabalin (e.g., Lyrica) can also be helpful to decrease symptoms.

When conservative measures are not sufficient, or if the patient cannot participate in physical therapy because of severe pain, steroids can be used to decrease the inflammation. Some physicians provide an oral steroid taper. These may be effective but are not specifically targeted to the site of inflammation and have greater systemic side effects.

A fluoroscopically guided epidural steroid injection can be very effective. The injection can be performed via either a transforaminal, interlaminar, or caudal route depending on the nerve roots involved. For most instances, the transforaminal route is favored.

If MRI reveals a contained disc bulge or protrusion to be causing symptoms, and if epidural steroid injection(s) and physical therapy do not treat the symptoms adequately, a percutaneous microdiscectomy or nucleoplasty may be appropriate. This procedure serves to essentially debulk or “shrink” the disc, thus taking the pressure off of the nerve root.

Persistent, debilitating symptoms despite aggressive nonsurgical care should prompt a surgical evaluation. Surgical options include discectomy and discectomy with fusion.

If the patient has progressive neurologic symptoms and/or bowel or bladder changes, a high index of suspicion must be maintained for cauda equina syndrome, which is a surgical emergency.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree