Abstract

Background

QT dispersion (QTd) is a marker of myocardial electrical instability, and is increased in metabolic syndrome (MetS). Moderate intensity continuous exercise (MICE) training was shown to improve QTd in MetS patients.

Objectives

To describe long-term effects of MICE and high-intensity interval exercise training (HIIT) on QTd parameters in MetS.

Methods

Sixty-five MetS patients (53 ± 9 years) were assigned to either a MICE (60% of peak power output [PPO]), or a HIIT program (alternating phases of 15–30 s at 80% of PPO interspersed by passive recovery phases of equal duration), twice weekly during 9 months. Ventricular repolarization indices (QT dispersion = QTd, standard deviation of QT = sdQT, relative dispersion of QT = rdQT, QT corrected dispersion = QTcd), metabolic, anthropometric and exercise parameters were measured before and after the intervention.

Results

No adverse events were noted during exercise. QTd decreased significantly in both groups (51 vs 56 ms in MICE, P < 0.05; 34 vs 38 ms in HIIT, P < 0.05). Changes in QTd were correlated with changes in maximal heart rate ( r = −0.69, P < 0.0001) and in heart rate recovery ( r = −0.49, P < 0.01) in the HIIT group only. When compared to MICE, HIIT training induced a greater decrease in weight, BMI and waist circumference. Exercise capacity significantly improved by 0.82 and 1.25 METs in MICE and HIIT groups respectively ( P < 0.0001). Lipid parameters also improved to the same degree in both groups.

Conclusion

In MetS, long-term HIIT and MICE training led to comparable effects on ventricular repolarization indices, and HIIT might be associated with greater improvements in certain cardiometabolic risk factors.

Résumé

Introduction

La dispersion du QT (QTd) est un marqueur d’instabilité électrique du myocarde, qui est allongé dans le syndrome métabolique (MetS). L’entraînement continu à intensité modérée (MICE) a montré son efficacité dans l’amélioration du QTd chez les patients MetS.

Objectifs

Décrire les effets à long terme d’un entraînement MICE et d’un entraînement par intervalles à haute intensité (HIIT) sur les paramètres du QTd dans le MetS.

Méthodes

Soixante-cinq patients (53 ± 9 ans) présentant un MetS ayant réalisé soit dans un programme MICE (60 % de la puissance maximale aérobie [PMA]), soit un programme HIIT (alternant des périodes de 15–30 s à 80 % de la PMA intercalées avec des périodes de récupération passive de même durée), deux fois par semaine pendant neuf mois ont été étudiés. Les caractéristiques de la repolarisation ventriculaire (dispersion du QT = QTd, déviation standard du QT = sdQT, dispersion de la durée du QT = rdQT, dispersion corrigée de la durée du QT = QTcd), les paramètres métaboliques, anthropométriques et d’exercices étaient mesurés avant et après le programme d’entraînement.

Résultats

Aucun effet indésirable n’a été rapporté pendant l’entraînement. Le QTd a diminué de façon significative dans les deux groupes (51 vs 56 ms dans le groupe MICE, p < 0,05 ; 34 vs 38 ms dans le groupe HIIT, p < 0,05). Les modifications du QTd étaient corrélées à celle de la fréquence cardiaque maximale ( r = 0,69, p < 0,0001) et de la fréquence cardiaque de récupération ( r = −0,49, p < 0,01) uniquement dans le groupe HIIT. Comparativement au MICE, l’entraînement HIIT a induit une diminution plus importante du poids, de l’IMC et du tour de taille. La capacité d’exercice a augmenté de façon significative de 0,82 et 1,25 METs respectivement pour les groupes MICE et HIIT ( p < 0,0001). Les paramètres du bilan lipidique se sont également améliorés de manière similaire dans les deux groupes.

Conclusion

Dans le syndrome métabolique, les entraînements HIIT et MICE induisent des effets positifs similaires sur les caractéristiques de la repolarisation ventriculaire, mais l’HIIT paraît être associé à des améliorations plus importantes sur certains facteurs de risque cardiométaboliques.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

QT dispersion (QTd) is the difference between the longest and the shortest QT intervals on a 12-lead ECG. QTd is a non-invasive method to assess myocardial electrical instability , and a predictor of ventricular arrhythmic events . QTd increase is thought to reflect higher sympathetic and lower parasympathetic inputs to the heart . In patients with a history of acute myocardial infarction, increased QTd is associated with a higher risk of ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death .

The metabolic syndrome (MetS) is associated with hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system and with increased QTd . Exercise training (ET) has been shown to reduce QTd in various populations including individuals with coronary heart disease (CHD) . We recently showed that moderate intensity continuous exercise (MICE) training also improves QTd in MetS subjects . It has been recently shown that high-intensity interval exercise (HIIT) is safe, well tolerated, and leads to superior improvements in exercise capacity and fitness when compared to MICE in various populations including those with obesity and MetS . All these studies used relatively long exercise intervals (2–4 minutes) at 85–95% of maximal heart rate (HR) or 120% of power at the ventilatory threshold . Previous studies in healthy subjects showed that protocols with shorter exercise intervals permit a longer total exercise time while allowing subjects to spend more time at a high percentage of VO 2 max leading to a greater training stimulus. We recently demonstrated similar results in overweight CHD and obese CHF patients . An “optimized” HIIT protocol consisting of 15–30 s exercise intervals with passive recovery phases of same duration was better tolerated and subjectively less difficult relative to interval training protocols with longer intervals and active recovery periods, thereby allowing subjects to train longer at a high percentage of VO 2 max . Furthermore, our optimized protocol appeared well tolerated, safe and was subjectively preferred by most subjects relative to an isocaloric MICE session .

Diet and exercise training (ET) together remain the cornerstone of treatment for subjects with obesity and MetS, but no data are available regarding the ventricular repolarization parameters and the effects of HIIT training in this growing population.

1.2

Objectives

Based on our previous researches in patients with CV , we hypothesized that introducing our optimized HIIT protocol in a long-term (9 months) lifestyle intervention (CV risk factors and nutritional counselling) would be safe, well tolerated and have positive effects on QT dispersion, cardiometabolic risk parameters, and exercise tolerance in subjects with MetS. The data present herein describe the results of the first year of implementation of this protocol in our center, compared to those obtained before the systematic use of HIIT.

1.3

Methods

This retrospective chart review study was conducted at the cardiovascular prevention and physical activity center of Montreal Heart Institute (ÉPIC center) and approved by the local ethics committee. Our centre provides a primary prevention multidisciplinary weight loss program (KILO-ACTIF) including lifestyle modification (education on risk factor control and nutrition counselling) and supervised exercise training, including resistance and aerobic exercise (either on a continuous or interval mode). All patients had a diagnosis of MetS at entry and all completed the program. Subjects with coronary heart disease (prior documented myocardial infarction, prior coronary revascularization, or documented myocardial ischemia on myocardial scintigraphy) were excluded.

Data were examined from a cohort of 65 MetS patients (mean age: 53 ± 9) consecutively enrolled in this program from 2008 to 2010, that were assigned to either a moderate intensity continuous training program (MICE group, n = 30, year 2008–2009) or an HIIT supervised training program (HIIT group, n = 35, year 2009–2010), two times a week during 9 months. Indeed, based on our team’s previous research works about HIIT in cardiac patients , this type of training was systematically implemented in the KILO-ACTIF program in 2009. Except for the aerobic exercise training protocols, the program was identical for both groups. All subjects underwent baseline physical examination, a treadmill maximal exercise test and blood sample analysis.

1.3.1

Metabolic syndrome definition

Metabolic syndrome was defined according to most recent criteria of the International Diabetes Federation : presence of an abdominal obesity (waist circumference [WC] ≥ 94 cm in men and ≥ 80 cm in women) plus any two of the following factors: triglycerides ≥ 1.70 mmol/l, decreased HDL-cholesterol (< 1.0 mmol/l in men and < 1.3 mmol/l in women), systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mmHg, and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 5.6 mmol/l. Patients receiving pharmacological therapy for either diabetes or hypertension were not excluded from our analyses.

1.3.2

Measurements

Anthropometric measurements included height, weight, and WC, measured with the patient standing, bare midriff, after a full expiration, with both feet touching and arms hanging freely. The measuring tape was placed perpendicular to the long axis of the body and horizontal to the floor, at the midpoint between the lowest rib and the iliac crest. Resting ECG, treadmill maximal exercise test and blood sample analysis including FPG and lipid profile were measured. Treadmill exercise testing was performed using a symptom-limited ramp protocol with a 5-min passive recovery period . During the tests, the subject’s ECG and blood pressure were monitored continuously. Maximal exercise tolerance was defined as the highest level of metabolic equivalent units (METs) achieved, and was estimated from maximal treadmill speed and grade during the treadmill . Heart rate recovery (HRR) was defined as HR one minute after the end of the exercise. All patients were instructed to take their usual medications prior to exercise testing.

1.3.2.1

Left ventricular repolarization parameters

All subjects underwent a routine standard 12-lead surface ECG recorded at a paper speed of 25 mm/s and gain of 10 mm/mV (MAC 5000, rest system ECG, GE Healthcare, Marquette, USA) in the supine position and were breathing freely but not allowed to speak during the ECG recording. The ECGs were recorded at baseline and at the end of follow-up. ECGs were transferred to a personal computer via scanner (Hewlett-Packard Scanjet 4370, USA), magnified, and QT measurement was performed manually using a commercial software (Adobe Photoshop CS2, Adobe Systems Incorporated, USA, 2005). The QT interval was measured from the beginning of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave at the level of the isoelectric baseline. If U waves were present, the QT interval was measured to the nadir of the curve between the T and U waves . QTd was assessed via four validated QTd parameters usually described in the literature :

- •

QT dispersion (QTd), defined as the difference between the maximal and the minimal QT interval across the 12-lead ECG, with at least eight interpretable leads;

- •

standard deviation of QT (sdQT) is the standard deviation of all QT measurements for each patient;

- •

relative dispersion of QT (rdQT), defined as sdQT/mean QT × 100;

- •

correction of QTd using Bazett’s formula (QTcd), defined as QTcd = QTd/√RR).

All ECG analyses were performed by two independent individuals (T.G. and J.D.), blinded to time and group. Inter-examiner reproducibility was previously assessed (intraclass correlation coefficient ranging from 0.58 to 0.91). Using Bland and Altman procedure, the average bias between the two examiners was found to be systematic (J.D. < T.G.) and comprised between −5.4 and −7.6 ms.

1.3.3

Exercise training

1.3.3.1

Aerobic exercise

All subjects underwent a personalized training program based upon the results of the initial symptom-limited exercise test. Exercise prescription and intensity were gradually increased through the training program according to each patient’s progress. Supervised exercise training was performed two times per week on an ergocycle (Precor, model 846i, USA) either on a MICE or HIIT mode, depending on the group. Based on our team’s previous research on HIIT in cardiac patients, the two modalities were designed to be roughly isocaloric . In addition, subjects were advised to perform one to two additional continuous moderate intensity sessions per week, such as walking and/or cycling (45 min duration, Borg scale level 12 to 14 outside the centre on a weekly basis). Exercise training program attendance was obtained from medical charts and from an electronic system which automatically records subject’s entries on our centre. A 100% adherence was defined as the achievement of at least two supervised sessions per week. Weekly unsupervised exercise training sessions and physical activity performed in and/or out the center were reported in a diary.

The MICE training sessions included a 5-min warm-up at low intensity followed by a 30-min period pedalling at 60% of peak power output (PPO) measured during the initial symptom-limited exercise test (Borg scale level 11–14), and a 5-min cool down period. PPO was estimated from the maximal METs treadmill value according to following methodology:

- •

METs treadmill value was converted into oxygen uptake expressed in mL/min/kg and mL/min;

- •

the VO 2 peak treadmill value in mL/min was then converted into VO 2 peak cycling value in mL/min by subtracting 16% ;

- •

finally, VO 2 peak cycling value in mL/min was converted into Watts using the gender specific conversion chart of Robergs .

The HIIT program was introduced in our centre in 2009 after our studies on optimized HIIT in overweight CAD and obese CHF patients . The first 2 weeks consisted of a familiarization period with the ergocycle, and with Borg scale rating of perceived exhaustion (RPE) (6–20 scale). Thereafter, HIIT began with the following protocol: after a 5-min warm-up at 50% of the PPO, each HIIT session was composed of two sets of 10 min of repeated bouts of 15 and/or 30 s at 80% of PPO interspersed by 15 and/or 30 s period of passive recovery, with the setting of the ergometer checked by the kinesiologist for each patient. The length of the intervals was chosen by the kinesiologist. The two sets of HIIT were separated with a 4-min passive recovery period. RPE was set at 15 during sessions and a 5-min cool down period at 50 watts was performed . Total HIIT session time was 34 minutes.

1.3.3.2

Resistance training

The sessions were prescribed according to recommendations and composed of 20 min of circuit weight training performed with free weights and elastic bands adapted to each patient’s capacities. Individualized training load target was 50% of maximal weight lifted (1-RM). 1-RM estimation was performed for each muscle group at baseline and re-performed when RPE was less than 15 on Borg scale during training sessions. Fifty percent of 1-RM estimation was performed using the method suggested by the American Heart Association for individuals with and without cardiovascular diseases, i.e. load allowing patient to achieve 15 repetitions . For each muscle group, patients performed one set of 15 to 20 repetitions, followed by a 30-s rest period, at a target RPE of 15.

1.3.3.3

Lifestyle intervention

All subjects underwent five face-to-face meetings with a dietician in our centre. First, eating habits and motivation were assessed, and the dietician described the main principles of the Mediterranean. The macronutrient composition (% daily calories) of this recommended diet was as follows: protein: 10%; carbohydrate: 55% (with a high intake of fibers); total fat: 36%; saturated fatty acids: 7%; mono-unsaturated fatty acids: 25%; polyunsaturated fatty acids: 2.5%, ω6/ω3 ratio = 3–6. There was no severe restriction regarding total daily energy consumption. The aim was to meet, as far as possible, the Canadian guidelines (2000–2400 kcal/day) , which are in line with the total energy intake described in the Mediterranean diet. At the micronutrient level, this diet is rich in vitamin A, C and E, selenium and polyphenols. During the subsequent visits at the 5th, 12th, 20th, and 36th weeks, the dietician checked comprehension of and adherence to the Mediterranean diet and answer any questions. Participants also received two group teaching sessions aimed at providing guidance regarding CV risk factor control, reading food labels and tasting Mediterranean-style dishes.

1.3.4

Statistical analysis

All group data are expressed as mean value ± standard deviation and/or in number and percentage. Normal distribution of the data was verified by a Shapiro-Wilk test. Data were logarithmically transformed when this assumption was not met. For continuous variables, statistical differences between groups and time were evaluated by a two-way repeated measure analysis of variance (group × time). A post hoc test (Scheffé test) was used to localize differences. Difference in medication prescription at baseline, cardiometabolic risks proportion and MetS prevalence at baseline and after the 9-month training period was tested using a Chi-square test. Associations between changes in QTd parameters and changes in metabolic (weight, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, FPG) and exercise parameters (PPO and maximal HR) were tested using Pearson test. All analyses were performed using SAS 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Statview 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

1.4

Results

All patients were able to complete HIIT sessions at the targeted intensity (80% of MAP for peaks). No adverse events were noted during HIIT training. There were no changes in medications related to cardiovascular risk factors during the program. The mean number of sessions per week was not different between the two groups (3.3 ± 1 and 2.9 ± 0.8 in MICE and HIIT groups, respectively; P = 0.4), and all patients performed at least the two main sessions per week. Table 1 describes the clinical characteristics of both groups at baseline. Briefly, patients had similar age and weight, however BMI, LDL- and HDL-cholesterol were all significantly lower in the MICE group. In contrast, the MICE group had a marked elevation in triglycerides (TG), whereas TG levels were normal in the HIIT group. The prevalence of abdominal obesity, hypertension, and abnormalities of glucose metabolism was not significantly different between groups.

| MICE ( n = 30) | HIIT ( n = 35) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.5 ± 9.6 | 54 ± 10.1 | NS |

| Male/Female ( n ) | 21/9 | 15/20 | P < 0.05 |

| Body mass (kg) | 94.6 ± 13.9 | 98.8 ± 18.3 | NS |

| Height (cm) | 170 ± 9 | 166 ± 9 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 32 ± 6 | 35.7 ± 5.1 | P < 0.05 |

| Medications , n (%) | |||

| Aspirin | 10 (33) | 8 (23) | NS |

| Beta-blockers | 6 (20) | 4 (11) | NS |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2 (7) | 5 (14) | NS |

| ACE inhibitors | 4 (13) | 4 (11) | NS |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 3 (10) | 5 (14) | NS |

| Statins | 10 (33) | 14 (40) | NS |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | 3 (10) | 4 (11) | NS |

1.4.1

Modifications of QTd parameters

Myocardial repolarization parameters are shown in Table 2 . QTd, QTcd and rdQT were significantly lower in the MICE group at baseline. After the intervention, all QTd parameters significantly decreased in both groups, except for sdQT.

| MICE | Pre-post difference | HIIT | Pre-post difference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 9 months | Δ in % | P value | Baseline | 9 months | Δ in % | P value | |

| QTd (ms) | 56 ± 18 a | 51 ± 20 | −9 | < 0.05 | 38 ± 9 a | 34 ± 9 | −11 | < 0.05 |

| QTcd (ms) | 65 ± 26 a | 57 ± 23 | −12 | < 0.05 | 41 ± 10 a | 37 ± 11 | −10 | < 0.05 |

| sdQT (ms) | 17 ± 5 | 16 ± 6 | −6 | NS | 12 ± 3 | 11 ± 3 | −8 | NS |

| RDQT | 5.4 ± 1.7 a | 5 ± 1.3 | −7 | NS | 3.2 ± 0.8 a | 3 ± 0.8 | −6 | NS |

1.4.2

Cardiometabolic risk factors and prevalence of metabolic syndrome

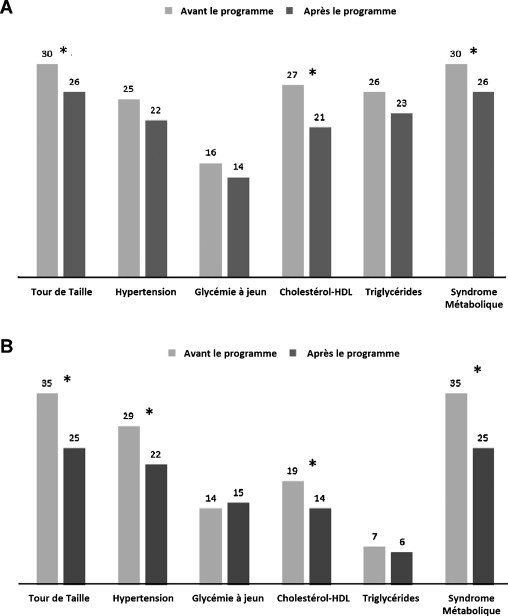

Table 3 describes the cardiometabolic risk factors at baseline and after the 9-month program. Bodyweight and BMI were significantly reduced in both groups, this reduction being greater in the HIIT group, while WC and diastolic blood pressure significantly decreased only in HIIT group. HDL-, LDL-cholesterol and TG also significantly decreased in both groups, with a greater reduction in TG and TG/HDL ratio in the MICE group. Prevalence of MetS and its components before and after the intervention are illustrated in Fig. 1 : the prevalence of MetS significantly decreased in MICE (from 30 to 26 patients, P < 0.05) and HIIT (from 35 to 25 patients, P < 0.05) groups, mainly due to a decrease in low-HDL status (both groups) and hypertension (HIIT group only).

| MICE | HIIT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 9 months | P value | Baseline | 9 months | P value | |

| Body weight (kg) | 94.64 ± 13.92 | 92.5 ± 13.6 | t* | 98.8 ± 18.3 | 93.9 ± 16.7 | i*, t § |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 109.1 ± 12.2 | 108.6 ± 12.1 | 113.4 ± 13.9 | 108 ± 12.6 | i*, t § | |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 32 ± 6 | 31.2 ± 5.9 | G*, t* | 35.7 ± 5.1 | 34 ± 4.8 | i*, t § |

| Rest SBP (mmHg) | 138.3 ± 17 | 133.3 ± 13.5 | 137.5 ± 13.9 | 132.3 ± 9.7 | t* | |

| Rest DBP (mmHg) | 82.2 ± 8.7 | 78.5 ± 7.7 | 82.3 ± 7.1 | 79.8 ± 5.9 | ||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 1.04 | t* | 5.17 ± 1.05 | 4.85 ± 0.89 | t ‡ |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.87 ± 0.16 | 1.02 ± 0.26 | G*, t ‡ | 1.21 ± 0.28 | 1.28 ± 0.31 | t* |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.88 ± 0.85 | 2.55 ± 0.88 | G*, t* | 3.31 ± 0.93 | 3.00 ± 0.77 | t* |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 2.97 ± 1.52 | 2.29 ± 1 | G*, t*, i* | 1.45 ± 0.60 | 1.30 ± 0.75 | t* |

| TC/HDL ratio | 5.61 ± 1.51 | 4.31 ± 1.36 | G*, t § , i* | 4.42 ± 0.91 | 3.92 ± 0.87 | t § |

| TG/HDL ratio | 3.17 ± 1.68 | 2.5 ± 1.17 | G*, t* | 1.32 ± 0.84 | 1.12 ± 0.85 | t* |

| Fasting glycaemia (mmol/L) | 5.8 ± 0.89 | 5.76 ± 1.16 | 5.33 ± 0.77 | 5.47 ± 0.73 | ||

1.4.3

Maximal exercise testing data

Maximal exercise testing data are reported in Table 4 . There was no difference in training compliance between the two groups, and exercise capacity significantly increased in both groups (+0.82 METs and +1.25 METs in MICE and HIIT groups respectively, both P < 0.0001). Resting HR significantly decreased only in the HIIT group, while heart rate recovery was unchanged after the program in both groups.

| MICE | HIIT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 9 months | P value | Baseline | 9 months | P value | |

| Training sessions (/week) | 3.2 ± 2.2 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | ||||

| Maximal exercise capacity (METs) | 8.08 ± 2.42 | 8.9 ± 2.57 | t § | 8.01 ± 1.51 | 9.32 ± 1.76 | t § |

| Resting HR (bpm) | 74.2 ± 15.9 | 70.9 ± 13.3 | 74.6 ± 14.1 | 68.3 ± 11.3 | t ‡ | |

| Maximal HR (bpm) | 144 ± 22.5 | 147.7 ± 20.2 | G* | 155.6 ± 18.2 | 158.7 ± 17.4 | |

| Recovery HR | −23.7 ± 11.7 | −22.1 ± 8.5 | −24 ± 9.2 | −25.5 ± 9.2 | ||

1.4.4

Associations between QTd and metabolic and exercise parameters

At baseline, QTd and QTcd correlated with age (QTd: r = 0.42, P < 0.05; QTcd: r = 0.38, P < 0.05), exercise tolerance (QTd: r = 0.3, P < 0.05; QTcd: r = 0.33, P < 0.01), and TG level (QTd: r = 0.37, P < 0.01; QTcd: r = 0.31, P = 0.01) in all subjects. No significant associations were identified between changes in QTd parameters and changes in metabolic and exercise parameters in the MICE group, whereas in HIIT group changes in QTd parameters correlated with changes in max HR (QTd: r = −0.69, P < 0.0001; QTcd: r = −0.65, P < 0.0001; sdQT: r = −0.62, P < 0.0001; rdQT: r = −0.57, P < 0.001) and changes in heart rate recovery (QTd: r = −0.49, P < 0.01; QTcd: r = −0.43, P < 0.001; sdQT: r = −0.4, P < 0.05; rdQT: r = −0.35, P < 0.05).

1.5

Discussion

In this cohort of MetS patients, a long-term lifestyle intervention including nutritional counselling and exercise training led to a significant decrease in most QTd parameters, irrespective of the type of the aerobic training. However, HIIT training was associated with a greater improvement in certain cardiometabolic risk factors (BMI, WC), with comparable effects on parameters of ventricular repolarization. These results showing the beneficial impact of a combined nutritional and exercise intervention on QTd are consistent with our previous finding in MetS patients as well as in other cardiac populations . Despite the fact that our intervention was longer than other ET programs reported above, we did not witness greater reductions in QTd parameters, irrespective of the type of ET. This could be due to the fact that QTd was at the upper limit of normal and not grossly increased .

The main findings of this study are that, when combined to a lifestyle intervention, HIIT training induces similar benefits on QT dispersion as does MICE training. While growing in popularity, HIIT has yet to be recommended in the scientific community due to fears of potential CV complications , particularly with respect to life-threatening arrhythmias in high-risk patients. Given that increased QTd is associated with an increased risk of sudden death, our results suggesting a beneficial effect of HIIT training on QTd to a similar degree as MICE training, is reassuring. Indeed, with the growing incidence of chronic disabling disease leading to increased sedentarity, MetS is more and more prevalent among patients benefiting from exercise as a part of their rehabilitation program.

If the influences of the autonomic nervous system on QTd are well known , the mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of ET on ventricular repolarization indices is still a matter of debate. The autonomic regulatory mechanism remains, however, one of the most considered hypotheses . Indeed, ET has been reported to positively influence the cardiovascular autonomic tone in healthy subjects, decreasing sympathetic tone while increasing vagal tone , as well as in cardiac patients after coronary artery bypass surgery . Concerning the effect of HIIT on autonomic CV regulation, data are limited. In athletes, it was shown that parasympathetic reactivation during the first 10 minutes of recovery after a repeated sprint exercise was significantly delayed, compared to an isocaloric moderate continuous exercise . However, using 24-hour Holter monitoring, Munk et al. showed the positive impact of HIIT on autonomic tone in CHD patients following percutaneous coronary intervention . More recently, Labrunee et al. presented preliminary results in 12 CHF patients (NYHA I-III) showing that the number of ventricular extrasystoles, couplets or runs of non-sustained ventricular tachyrardia over 24 hours was significantly lower after HIIT than after both continuous exercise and no exercise . These changes appeared to be correlated with improvements in sympathovagal balance due to better reactivation of parasympathetic tone notably during the first 3 hours after exercise. Our data showing a correlation between changes in QTd and heart rate recovery in the HIIT group could indirectly reflect a greater impact on parasympathetic tone of HIIT training .

HIIT led to significantly greater improvements in certain cardiometabolic risk factors, i.e. BMI and WC, which are strong independent predictors of mortality in the general population . However, subjects in the MICE training group presumably had a higher degree of insulin resistance, as witnessed by the higher baseline fasting glucose, TG levels and TG/HDL ratio , which could inluence the results of ET on the reduction in WC. The higher TG levels at baseline could also explain the greater QTd dispersion, as previously reported by Szabo et al. Indeed, the difference in QTd and QTcd was statistically significant at baseline between the two groups (18 and 24 ms, P < 0.05), and largely greater than the inter-examiner average bias (5.4–7.6 ms), which suggests a real group effect. Our results regarding the change in lipid parameters over time and exercise tolerance are slightly different from those reported by Tjonna et al. in MetS patients undergoing MICE or HIIT exercise . They noted a 35% increase in VO 2 max in the HIIT group (12 patients) versus a 16% increase in the MICE group (10 patients). The discrepancy in results could be due to difference in the HIIT protocol, and the duration of the ET program, as well in patient profile (older subjects in our study with higher TG levels) and different definitions used for abdominal obesity. We chose the 94 and 80 cm cut-off in men and women, respectively, because our sample exclusively contained Europids. Indeed, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) stated in 2006 that “in future studies of populations of Europid origin (white people of European origin, regardless of where they live in the world), prevalence should be given, with both European and North American cut-offs to allow better comparisons” . Finally, the difference obtained using either Adult Treatment Panel III values or IDF definitions was minimal, as only two men had WC less than 102 cm, and one women less than 88 cm.

While improvements in several metabolic and exercise parameters were observed, none were associated with the improvements in QTd witnessed, except for changes in maximal heart rate in the HIIT group. These findings would suggest that in our study exercise training directly contributed to improve myocardial repolarization, independent of the improvement in metabolic or exercise parameters. Other potential mechanisms whereby ET might improve QTd are through improvements in risk factor control including weight loss and/or triglycerides level decrease. Indeed, weight loss in obese subjects has been shown to significantly decrease QTd, with the amount of improvement in QTd being proportional to the degree of weight loss . As mentioned previously, weight loss was not associated with improvements in QTd in our study. Studies evaluating the impact of glucose, blood pressure or lipid control interventions on QTd parameters have yet to be performed.

1.5.1

Study limitations

There are limitations inherent with the study design. First, this was a non-randomized, observational, and retrospective study. This explains the “non-comparability” of the two groups with respect to certain baseline characteristics, notably the baseline QT dispersion parameters and the number of women or diabetics in each group. We also did not include a control group (i.e. receiving no diet or exercise intervention). However, prior studies evaluating the effectiveness of exercise-training programs in obese patients with MetS did not show significant improvements in exercise or metabolic parameters in the control groups. Moreover, the relative contribution of HIIT or MICE, resistance training and diet could not be assessed, since a combined lifestyle and HIIT intervention was executed. Second, our results represent the experience of one single institution, probably affected by recruitment bias, and may not be generalized to all MetS subjects. However, we do believe that HIIT is feasible, less monotonous, and can potentially enhance a subject’s adherence to exercise training, while being time-efficient to improve body composition, cardiovascular risk and exercise capacity. Moreover, our results are based on a “real life” clinical program performed in a tertiary care center that reflects results observed in routine clinical settings, compared to randomized studies with more selected patients. Third, our sample size was quite small. Nevertheless, we were able to identify significant improvements in QTd parameters in both groups.

1.6

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggest that, when combined to a lifestyle intervention, HIIT training induces benefits on QT dispersion as does MICE training. In addition, HIIT training program may be associated with a greater improvement in some cardiometabolic risk factors. Although concomitant improvements in exercise tolerance and metabolic parameters were observed, the improvements in QTd parameters observed appeared to be related primarily to the effects of physical training rather than secondarily via an improvement in the metabolic profile. These pilot results provide the rationale for further randomized studies to confirm the safety and efficiency of HIIT in MetS patients, and thus broaden its prescription.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Funding : no financial support.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La dispersion du QT (QTd) se définit comme la différence entre l’intervalle le plus long et le plus court du segment QT sur un électrocardiogramme (ECG) à 12 dérivations. La mesure du QTd est une méthode non invasive pour évaluer l’instabilité électrique du myocarde et est un facteur prédictif d’épisodes d’arythmie ventriculaire . Une augmentation du QTd semble refléter une augmentation du tonus sympathique et une baisse du tonus parasympathique . Chez les patients avec des antécédents de syndrome coronarien, un QTd élevé est associé à un risque accru de fibrillation ventriculaire et de mort subite .

Le syndrome métabolique (MetS) est associé à une hyperactivation du système nerveux sympathique et à une augmentation du QTd . La réalisation d’un programme d’exercice (ET) a montré son efficacité sur la réduction du QTd au sein de différentes populations, y compris chez des patients coronariens . Nous avons récemment montré qu’un programme d’entraînement continu à intensité modérée (MICE) améliorait le QTd chez les patients MetS . Par ailleurs, il a été rapporté que l’entraînement par intervalles à haute intensité (HIIT) était sans danger, bien toléré et apportait des améliorations plus importantes de la capacité d’exercice et de la forme physique que le MICE dans différentes populations y compris des patients obèses , ou avec un MetS . Toutes ces études utilisaient des intervalles d’exercice relativement longs (2–4 minutes) à 85–95 % de la fréquence cardiaque maximale (FCmax) ou à 120 % de la puissance au seuil d’adaptation ventilatoire . Les études précédentes chez le sujet sain ont montré que des protocoles avec des intervalles d’exercice plus courts permettaient de rallonger le temps total d’exercice tout en permettant aux sujets de passer plus de temps à un pourcentage plus élevé de VO 2 max , ce qui conduit à un stimulus d’entraînement supérieur. Nous avons récemment rapporté des résultats similaires chez des patients coronariens en surpoids et des patients insuffisants cardiaques chroniques obèses . Un protocole HIIT « optimisé » comportant des intervalles d’exercice de 15–30 secondes avec des périodes de récupération passive de la même durée est apparu mieux toléré et subjectivement moins difficile que les protocoles avec des intervalles d’exercice et des périodes de récupération active plus longs, permettant ainsi aux sujets de s’entraîner plus longtemps à un pourcentage plus élevé de VO 2 max . De plus, notre protocole optimisé semble bien toléré, sans danger et avoir la préférence subjective de la plupart des sujets par rapport à un exercice MICE isocalorique . Une alimentation équilibrée et une activité physique régulière restent les bases du traitement pour les sujets obèses avec syndrome métabolique, cependant il n’existe aucune donnée sur l’impact de l’entraînement HIIT sur les paramètres de la repolarisation ventriculaire dans cette population grandissante.

2.2

Objectifs

Compte tenu de nos travaux précédents sur les patients coronariens , nous avons émis l’hypothèse qu’introduire notre protocole HIIT optimisé au sein d’une intervention thérapeutique prolongée (neuf mois) associant éducation sur les facteurs de risque cardiométaboliques, conseils nutritionnels et exercice serait sans danger, bien toléré et aurait un impact positif sur la dispersion du QT, les facteurs de risque cardiométaboliques et la capacité d’effort chez les sujets souffrant de MetS. Les données présentées dans cette étude décrivent les résultats de la première année de mise en place de ce protocole dans notre centre et sont comparées à celles obtenues avant l’utilisation systématique de l’HIIT.

2.3

Méthodes

Cette étude rétrospective sur les dossiers médicaux des patients s’est déroulée dans le centre de prévention cardiovasculaire et d’activités physiques de l’Institut de cardiologie de Montréal (centre ÉPIC) et a été approuvée par le comité local de protection des personnes. Notre centre propose un programme multidisciplinaire de perte de poids en prévention primaire (programme « KILO-ACTIF ») qui comprend des changements d’habitudes de vie (éducation thérapeutique sur le contrôle des facteurs de risque et conseils diététiques) et un programme d’exercice supervisé, incluant des exercices de renforcement musculaire et des exercices aérobies (en mode continu ou intermittent). Tous les patients avaient un diagnostic de syndrome métabolique validé à l’inclusion et ont terminé le programme. Les patients coronariens (avec antécédents documentés : syndrome coronarien aigu, revascularisation coronarienne ou ischémie myocardique démontrée par scintigraphie myocardique) furent exclus. Les données de l’étude concernaient une cohorte de 65 patients MetS (âge moyen : 53 ± 9) enrôlés de manière consécutive dans ce programme de 2008 à 2010. Ces patients furent inclus soit dans le programme d’entraînement continu à intensité modérée (groupe MICE, n = 30, année 2008–2009), soit dans le programme d’entraînement supervisé HIIT (groupe HIIT, n = 35, année 2009–2010), deux fois par semaine pendant neuf mois. En effet, comme présenté dans les travaux précédents de notre équipe sur l’HIIT chez le patient cardiaque , ce type d’entraînement a été mis en place systématiquement au sein du programme KILO-ACTIF en 2009. À part pour les protocoles d’exercices aérobie, le reste du programme était identique dans les deux groupes. À l’inclusion, tous les sujets ont bénéficié d’une consultation médicale, d’un test d’effort sur tapis roulant et d’analyses sanguines.

2.3.1

Définition du syndrome métabolique

La définition retenue était la plus récente de la Fédération internationale du diabète (IDF) : présence d’une obésité abdominale (tour de taille [TT] ≥ 94 cm chez l’homme et ≥ 80 cm chez la femme) associée à deux des facteurs de risque suivants : triglycérides supérieurs ou égaux à 1,70 mmol/L, taux réduit de cholestérol HDL (< 1,0 mmol/L chez l’homme et < 1,3 mmol/L chez la femme), pression artérielle systolique supérieure ou égale à 130 mmHg ou pression artérielle diastolique supérieure ou égale à 85 mmHg, et mesure de glycémie à jeun (GJ) supérieure ou égale à 5,6 mmol/L. Les patients traités pour diabète ou hypertension n’étaient pas exclus de nos analyses.

2.3.2

Mesures

Les paramètres anthropométriques mesurés étaient : la taille, le poids et le TT. Pour la mesure du TT, le patient se tenait debout, taille découverte avec les deux pieds se touchant et les bras le long du corps. Les mesures étaient réalisées après expiration complète. Le ruban à mesurer était placé à mi-distance entre la dernière côte et le haut de la crête iliaque antérosupérieure. Les autres éléments suivants étaient recueillis : ECG au repos, test d’effort sur tapis roulant et analyses sanguines comprenant la glycémie à jeun et le profil lipidique. Le test d’effort limité par les symptômes se faisait sur tapis roulant avec une période de cinq minutes de récupération passive . Pendant les tests, l’examinateur surveillait continuellement l’ECG et la tension artérielle du patient. La tolérance maximale à l’exercice était définie comme le plus haut niveau d’équivalent métabolique atteint et était calculée à partir de la vitesse maximale et du pourcentage d’inclinaison du tapis roulant durant l’exercice . La fréquence cardiaque de récupération (FCR) correspondait à la fréquence cardiaque relevée une minute après la fin de l’exercice. Tous les patients devaient prendre leur traitement pharmaceutique habituel avant le test d’effort.

2.3.2.1

Paramètres de repolarisation du ventricule gauche

Tous les sujets bénéficiaient d’un ECG standard 12 dérivations (vitesse de défilement : 25 mm/s et sensibilité : 10 mm/mV) (MAC 5000, rest system ECG, GE Healthcare, Marquette, États-Unis). Les sujets étaient en position allongée et pouvaient respirer librement mais sans parler durant l’ECG. Les tracés ECG étaient enregistrés à l’inclusion et à la fin du suivi, ils étaient ensuite transférés sur ordinateur à l’aide d’un scanner (Hewlett-Packard Scanjet 4370, États-Unis), puis amplifiés, et la mesure du QT était faite manuellement à l’aide d’un logiciel commercialisé (Adobe Photoshop CS2, Adobe Systems Incorporated, États-Unis, 2005). L’intervalle QT correspondait à la durée entre le début de l’onde QRS et la fin de l’onde T au niveau de la ligne isoélectrique. En cas de présence d’ondes U, l’intervalle du QT était mesuré jusqu’au creux de l’intervalle entre les ondes T et U . La QTd était évaluée à l’aide de quatre paramètres validés et couramment décrits dans la littérature :

- •

la dispersion du QT (QTd) correspond à la différence entre l’intervalle QT minimal et maximal sur le tracé ECG à 12 déviations avec au moins huit déviations interprétables ;

- •

déviation standard du QT (sdQT) : déviation standard de toutes les mesures du QT pour chaque patient ;

- •

dispersion de la durée du QT, définie comme la sdQT divisée par moyenne du QT × 100 ;

- •

la dispersion corrigée de la durée du QT calculée avec la formule de Bazett (QTcd) : QTcd = QTd/√RR.

Toutes les analyses ECG étaient menées par deux personnes indépendantes (T.G. et J.G.), ignorant le groupe et la période d’inclusion. Nous avons évalué la reproductibilité inter-examinateurs (coefficient de corrélation intraclasse allant de 0,58 à 0,91). À l’aide de la méthode de Bland et Altman, nous avons montré que le biais moyen entre les deux examinateurs était systématique (J.D. < T.G.) et compris entre −5,4 et −7,6 ms.

2.3.3

Entraînement

2.3.3.1

Exercice aérobie

Tous les patients participaient à un programme d’entraînement individualisé en fonction des résultats du test d’effort. La prescription d’exercice et l’intensité augmentaient régulièrement au cours du programme selon les progrès du patient. Les exercices supervisés avaient lieu deux fois par semaine sur un cycloergomètre (Precor, model 846i, États-Unis) sur le mode MICE ou HIIT suivant le groupe. Selon nos expériences précédentes d’un programme HIIT chez les patients cardiaques, les deux modalités étaient globalement isocaloriques . De plus, les sujets avaient pour consignes de pratiquer une à deux sessions supplémentaires d’exercice continu à intensité modérée, comme la marche ou le vélo (durée de 45 minutes, niveau 12 à 14 sur l’échelle de Borg) en dehors du centre et de façon hebdomadaire. La participation au programme était estimée à partir des dossiers médicaux et des données d’un système électronique enregistrant automatiquement l’entrée des patients dans notre centre. Une participation de 100 % correspondait à la réalisation d’au moins deux sessions supervisées par semaine. Les exercices et activités physiques hebdomadaires non supervisés dans et/ou hors du centre étaient colligés dans un journal.

Les sessions de l’entraînement MICE comprenaient cinq minutes d’échauffement à faible intensité, une période de pédalage de 30 minutes à 60 % de la capacité maximale d’exercice mesurée durant le test d’effort initial (niveaux 11–14 sur l’échelle de Borg) et cinq minutes de récupération active. La capacité d’exercice était calculée à partir de la valeur maximale d’unités d’équivalent métabolique (METs) obtenue sur le tapis roulant suivant la méthodologie suivante :

- •

la valeur METs obtenue sur tapis roulant était transformée en consommation d’oxygène exprimée en mL/min/kg et mL/min ;

- •

la valeur VO 2 pic tapis roulant était ensuite convertie en valeur VO 2 pic de pédalage en mL/min en soustrayant 16 % ;

- •

et enfin la valeur VO 2 pic de pédalage en mL/min était convertie en Watts en utilisant le tableau de conversion spécifique de Robergs .

Le programme HIIT a été introduit dans notre centre en 2009 après nos études sur un protocole « optimisé » HIIT chez les patients coronariens en surpoids et les patients obèses en insuffisance cardiaque . Les deux premières semaines consistaient en une période de familiarisation avec le cycloergomètre en utilisant l’échelle de Borg pour mesurer la perception de l’effort (RPE) (échelle 6–20). Par la suite, le programme HIIT commençait avec le protocole suivant : après cinq minutes d’échauffement à 50 % de la capacité maximale d’exercice, chaque session HIIT comprenait deux sessions de dix minutes d’exercice répétés d’une durée de 15 et/ou 30 secondes à 80 % de puissance maximale d’exercice (MAP) entrecoupées de périodes de récupération passive de 15 et/ou 30 secondes, sous la supervision d’un kinésithérapeute qui vérifiait les paramètres du cycloergomètre pour chaque patient. Le kinésithérapeute décidait de la durée des intervalles. Les deux périodes d’HIIT étaient séparées d’une période de récupération de quatre minutes. Le niveau de perception de la fatigue (RPE) cible était à 15 durant les périodes d’HIIT, qui étaient suivies d’une période de récupération de cinq minutes à 50 watts . La durée totale d’une session HIIT était de 34 minutes.

2.3.3.2

Renforcement musculaire

Les sessions étaient prescrites suivant les recommandations habituelles et se composaient de 20 minutes de renforcement musculaire en circuit avec des poids et des élastiques, adapté aux capacités de chaque patient. La charge cible, calculée individuellement, correspondait à 50 % du poids maximum soulevé (1-RM). L’estimation de la 1-RM était calculée pour chaque groupe musculaire à l’inclusion et recalculée de nouveau quand la RPE était inférieure à 15 sur l’échelle de Borg durant les séances d’entraînement. Elle était estimée par la méthode suggérée par l’American Heart Association pour les individus avec et sans maladies cardiovasculaires, définissant 50 % de la 1-RM comme le poids permettant aux patients d’effectuer 15 répétitions . Pour chaque groupe musculaire, les patients complétaient une série de 15 à 20 répétitions, suivi d’une période de repos de 30 secondes, à une RPE cible de 15.

2.3.3.3

Habitudes alimentaires

Tous les sujets ont eu cinq consultations avec une diététicienne du centre. Premièrement, les habitudes alimentaires et la motivation étaient évaluées et la diététicienne décrivait les principes du régime méditérranéen. La composition nutritionnelle (% apports journaliers recommandés – AJR) de ce régime était la suivante : protéines : 10 % ; glucides : 55 % (avec un pourcentage élevé de fibres) ; lipides: 36 % ; acides gras saturés : 7 % ; acides gras mono-insaturés : 25 % ; acides gras polyinsaturés : 2,5 %, ratio ω6/ω3 = 3–6. Il n’existait pas de restriction sévère sur le nombre total de calories journalières. Le but était de se rapprocher au plus près des recommandations canadiennes (2000–2400 kcal/j) , qui sont en accord avec l’apport calorique journalier décrit dans le régime méditérranéen. Au niveau de la composition nutritionnelle, ce régime est riche en vitamines A, C et E, sélénium et polyphénols. Au cours des visites suivantes à la cinquième, 12 e , 20 e et 36 e semaine, la diététicienne s’assurait de la compréhension et de l’adhésion au régime méditérranéen et répondait aux questions des participants. Ceux-ci participaient également à deux sessions d’éducation thérapeutique en groupe destinées à fournir des conseils sur le contrôle des facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire, la lecture des étiquettes, et la confection et dégustation des plats méditerranéens.

2.3.4

Analyse statistique

Toutes les données pour les deux groupes sont exprimées en valeur moyenne ± écart-type et/ou nombre et pourcentage. La normalité de la distribution des données était vérifiée à l’aide du test de Shapiro-Wilk. Dans le cas contraire, les données étaient transformées de façon logarithmique. Pour les variables continues, les différences statistiques entre les groupes et les périodes de temps étaient évaluées à l’aide d’une analyse de variance à mesures répétées et à deux facteurs (groupe × temps). Un test post hoc (test de Scheffé) servait à localiser les différences. Pour tester les différences concernant le traitement médicamenteux, la proportion de facteurs de risque cardiométaboliques et de prévalence MetS à l’inclusion et après le programme d’entraînement de neuf mois, nous avons utilisé un test χ 2 . Le test de Pearson était utilisé pour tester les associations entre changements des paramètres de QTd et changements métaboliques (poids, IMC, tension artérielle systolique et diastolique, triglycérides, cholestérol HDL, glycémie à jeun) et paramètres d’exercice (capacité maximale d’exercice et FCmax). Toutes les analyses ont été faites avec les logiciels SAS 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, États-Unis) et Statview 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, États-Unis). Une valeur p ≤ 0,05 était considérée comme statistiquement significative.

2.4

Résultats

Tous les patients ont complété leurs sessions HIIT à l’intensité cible (80 % de la puissance maximale pour les pics). Aucun effet secondaire n’a été noté durant l’entraînement HIIT. Aucun changement de traitement médicamenteux lié aux facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire n’a été mis en place au cours du programme. Le nombre moyen de sessions hebdomadaires était similaire dans les deux groupes (3,3 ± 1 et 2,9 ± 0,8 pour les groupes MICE et HIIT respectivement ; p = 0,4), et tous les patients participaient au moins à deux sessions par semaine. Le Tableau 1 décrit les caractéristiques cliniques des deux groupes à l’inclusion. Brièvement, les patients étaient d’âge et poids similaires, cependant l’IMC, les taux de cholestérol LDL et HDL étaient significativement plus bas dans le groupe MICE. En revanche, le groupe MICE présentait un taux élevé de triglycérides, alors que le taux était normal dans le groupe HIIT. Il n’y avait pas de différence significative de la prévalence de l’obésité abdominale, de l’hypertension et des anomalies du métabolisme glucidique entre les deux groupes.