Latissimus Transfer in the Setting of Irreparable Posterosuperior Rotator Cuff Tears

Jesse A. McCarron

Joseph P. Iannotti

DEFINITIONS

Latissimus dorsi transfer (with or without concomitant teres minor transfer) can be used in properly selected patients to improve active range of motion in the setting of irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears.

Tendon transfer to the superior aspect of the humeral head (superior transfer) has been described as a technique for improving active elevation and decreasing pain in younger patients, without pseudoparalysis, fixed superior migration, or arthritic changes in the glenohumeral joint.

Tendon transfer to the lateral aspect of the proximal humerus (lateral transfer, also known as L’Episcopo procedure) has been described as a technique for improving active external rotation. Currently, it is most commonly used in the setting of reverse shoulder arthroplasty to prevent a large external rotation lag sign or hornblower’s sign.

Irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears are tears that involve the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons, where there is an inability to repair the tendons back to the anatomic footprint of the greater tuberosity with the arm at the side.

Some tears can be determined to be irreparable preoperatively, if the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans demonstrate severe muscle atrophy of the supraspinatus or infraspinatus muscles.

This may help indicate that a patient has an irreparable tear and may be a candidate for muscle transfer, but the final determination of whether a tear is reparable is made at the time of surgery.

ANATOMY

The latissimus dorsi is normally an adductor and internal rotator of the humerus; however, after transfer, it is expected to act as an abductor and external rotator of the humerus.

The ability of the patient to retrain his or her neural pathways to achieve this active in-phase function varies dramatically.

In some cases, the latissimus dorsi transfer has only a tenodesis effect.

Originating from the supraspinatus and infraspinatus fossa, respectively, the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle-tendon units become confluent and insert as a common tendon on the greater tuberosity of the humerus immediately lateral to the humeral head articular margin.

Their combined footprint area averages 4.02 cm2.

The insertion of the supraspinatus averages 1.27 cm from medial to lateral and 1.63 cm from anterior to posterior.

The infraspinatus insertion averages 1.34 cm medial to lateral and 1.64 cm anterior to posterior.8

Over the superior aspect of the glenohumeral joint, the deepest fibers of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons are intimately interwoven with the joint capsule such that the rotator cuff tendons and joint capsule function as a single unit. As a result, rotator cuff tears involving the supraspinatus or infraspinatus tendons result in direct communication between the glenohumeral and subacromial spaces.

The latissimus dorsi muscle has a broad origin from the aponeurosis of spinous processes T7 through L5, the sacrum, the iliac wing, ribs 9 through 12, and the inferior border of the scapula.

The latissimus dorsi tendon averages 3.1 cm wide and 8.4 cm long at its insertion between the pectoralis major and teres major tendons on the proximal medial humerus.18

The fibers of the latissimus dorsi twist 180 degrees from origin to insertion, allowing the latissimus dorsi muscle to originate posterior to the teres major muscle on the posterior chest wall but insert immediately anterior to the teres major tendon on the proximal humerus.

The latissimus dorsi humeral insertion never extends more distal along the shaft than that of the teres major.

In most patients, the latissimus dorsi and teres major tendons insert separately onto the proximal humerus; however, 30% of patients have conjoined latissimus dorsi and teres major tendons that cannot be separated without sharp dissection.18

The neurovascular pedicle to the latissimus dorsi is the thoracodorsal artery and nerve (posterior cord, C6 and C7). The thoracodorsal artery and nerve enter the anteroinferior surface of the latissimus dorsi, about 13 cm from the humeral insertion site.

Anatomic studies have shown that this neurovascular pedicle is of adequate length to allow transfer and excursion of the latissimus dorsi to the superior or lateral proximal humerus without risk of undue tension, once any adhesions and fibrous bands have been released from the anterior surface of the muscle belly.20

The neurovascular pedicle to the teres major is the lower subscapular nerve (posterior cord, C5 and C6). The artery and nerve enter the teres major at an average of 7.4 cm medial to the humeral insertion site.18

Several important neurovascular structures lie close to the latissimus dorsi insertion, and careful attention to these structures must be given at the time of its release from the humerus to avoid injury.

Anterior to the latissimus, the radial nerve passes an average of 2.4 cm medial to the humeral shaft at the superior border of the tendon.

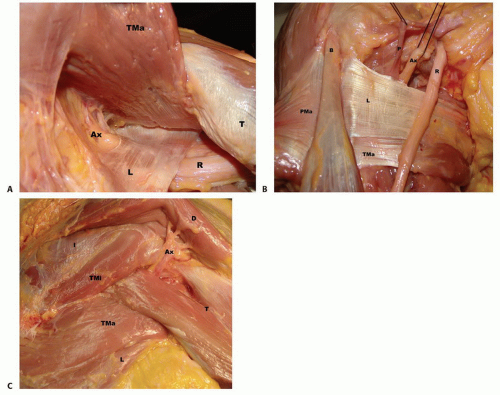

This distance increases with external rotation and abduction and decreases with internal rotation and adduction3 (FIG 1A,B).

The axillary nerve runs superior to the latissimus dorsi tendon before exiting the quadrangular space (FIG 1C). In neutral rotation and adduction, the average distance between the nerve and the superior border of the tendon is 1.9 cm.

This distance increases with external rotation and abduction and decreases with internal rotation.3

The anterior humeral circumflex artery runs along the superior border of the latissimus dorsi tendon.

PATHOGENESIS

Multiple causes have been proposed for the development of rotator cuff tears, including decreased vascular supply, mechanical compression between the humeral head and the coracoacromial ligament or the undersurface of the acromion, and traumatic causes such as humeral head dislocation or rapid or repetitive eccentric loading of the rotator cuff muscle-tendon units.5

Isolated, acute traumatic events may cause massive rotator cuff tears, the majority of which can be repaired open or arthroscopically if diagnosis and surgical intervention are timely.

Alternatively, most degenerative tendon tears start small and progressively get larger until the muscle retraction, muscle atrophy, and tendon loss prevent primary repair.

Tear size may not predict reparability at the time of surgery, but it does influence healing postoperatively, with larger tears having a lower incidence of healing.

Tissue quality and tendon retraction are the major determinants intraoperatively of whether a repair is possible. These factors also influence healing of a primary repair.

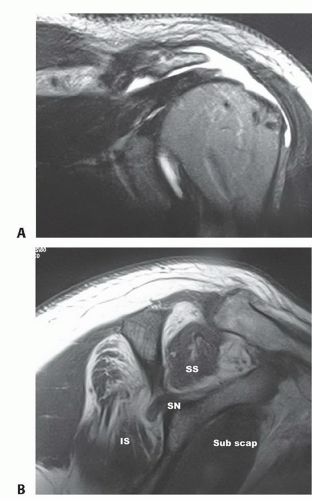

Increased size and duration of a tear lead to retraction of the rotator cuff and fatty infiltration of the muscle belly within weeks to months of developing a tear. These changes result in decreased tendon excursion and tissue compliance that is often irreversible (FIG 2).

As a result, the longer these massive tears go untreated, the higher the likelihood that the tear will be irreparable at the time of surgery, thus requiring either a superior latissimus dorsi transfer to restore overhead elevation in select patients or requiring reverse shoulder arthroplasty with possible lateral transfer of the latissimus dorsi to restore active external rotation.

Presentation of the patient with a massive irreparable cuff tear is often precipitated by a minor traumatic event such as a fall onto an outstretched hand, resulting in an acute-on-chronic tear and functional decompensation of the shoulder. Others present with a history of long-standing, worsening symptoms that finally reach a point that is no longer tolerable to the patient.

NATURAL HISTORY

Massive posterosuperior rotator cuff tears are uncommon, representing less than one-third of all rotator cuff tears even in practices limited to the treatment of shoulder pathology.21

Not all patients with large posterosuperior cuff tears experience enough loss of function or pain to require surgery or even seek treatment.

It can be difficult to predict who will have significant shoulder dysfunction based on radiographic or MRI findings or direct inspection of a torn rotator cuff.

Some patients with large tears can still use their arm for many activities, and some even retain the ability to perform overhead activities.

Others with smaller tears may have significant difficulty or an inability to use their arm for anything above chest level.

Loss of active external rotation and the presence of an external rotation lag sign usually signifies larger tears that extend into the lower half of the infraspinatus down to the level of the teres minor.

Regardless of tear size, it is loss of the rotator cuff muscles’ ability to perform their role as humeral head stabilizers that eventually leads to functional decompensation.

As the tear progresses in size, behavioral and biomechanical compensation will allow maintenance of function to a point. However, once the rotator cuff can no longer stabilize the humeral head to create a fulcrum around which the deltoid can act to forward flex and abduct the arm, rapid decompensation, loss of function, and increased pain ensue.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The patient history should elicit the mechanism and duration of the current symptoms with the intent of determining if there was a specific traumatic event leading to the rotator cuff tear and whether symptoms of rotator cuff pathology were present before any such event.

Determining if the tear is a result of an acute injury as opposed to an acute-on-chronic process will help in estimating the quality of the tissues and whether they will be amenable to repair at the time of surgery.

The duration of dysfunction is also important in determining the likelihood of being able to repair any rotator cuff tear because fatty degeneration of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle bellies may start within weeks of the injury and will greatly decrease tissue compliance and increase tension placed on a potential repair.13,22

A careful neurologic examination, starting with the neck, must be performed to rule out neurologic causes of shoulder symptoms.

An understanding of the patient’s current functional limitations as well as expectations for postoperative function is necessary to help determine if the patient’s disability is significant enough to benefit from a procedure.

A focused examination for the rotator cuff-deficient shoulder includes, but is not limited to, the following:

Active forward flexion: Patients with function at or above shoulder level are more likely to have improved active forward flexion postoperatively following superior tendon transfer.

Less than 90 degrees of active elevation or superior escape, where the humeral head translates anteriorly and superiorly out from under the coracoacromial arch in the setting of an irreparable rotator cuff tear, are both associated with a low chance of satisfactory outcome following superior latissimus dorsi transfer.

Active external rotation: Decreased external rotation on the affected side indicates partial or complete loss of infraspinatus function due to tear involvement or muscle dysfunction.

External rotation lag sign: Inability to maintain maximal external rotation (greater than or equal to a 20-degree lag sign) suggests tear extension well into the infraspinatus. The majority of these patients also lack active elevation and are not good candidates for superior tendon transfer but may be candidates for reverse shoulder arthroplasty to restore elevation with concomitant lateral tendon transfer to restore active external rotation.

Passive range of motion should be compared to the contralateral limb. Decreased range of motion suggests joint contracture, which requires treatment before consideration for muscle transfer.

Modified belly press test: Inability to perform this action demonstrates a dysfunctional or torn subscapularis tendon, and these patients will have a higher rate of clinical failure with muscle transfer.

Abduction strength testing: This tests deltoid muscle strength. A weak deltoid suggests less postoperative active range of motion secondary to inadequate strength.

External rotation strength testing: Full strength suggests no infraspinatus tear involvement, whereas weakness suggests progressive infraspinatus involvement or dysfunction.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

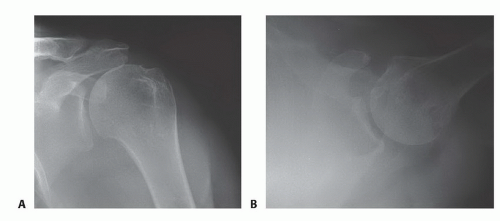

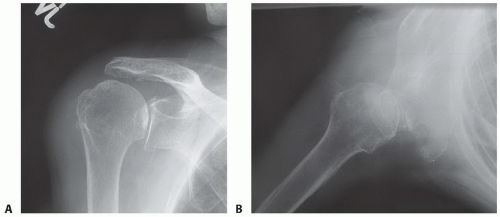

A true anteroposterior (AP) radiographic view of the shoulder in the plane of the scapula and axillary view is obtained (FIG 3A,B).

This allows evaluation of glenohumeral arthritis, superior migration of the humeral head, and identification of any abnormal bony anatomy (FIG 4A,B).

MRI allows evaluation of the rotator cuff, biceps tendon, and labral and capsular pathology (see FIG 2):

The size of the rotator cuff tear, especially the extent of subscapularis and infraspinatus involvement

Distance of tendon retraction from the greater tuberosity

Extent of fatty degeneration seen in involved muscle bellies

Electromyography is used to evaluate nerve function around the shoulder girdle.

It is necessary when nerve pathology is suspected as a cause of shoulder dysfunction.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Frozen shoulder

Adhesive capsulitis

Massive rotator cuff tear that can be repaired

Cervical nerve root compression

Suprascapular nerve palsy

Deltoid dysfunction

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management is directed toward optimizing the patient’s current function, managing pain, and modifying activities and expectations.

Treatment of irreparable cuff tears begins with physical therapy focused on maintaining motion and strengthening the deltoid and scapular stabilizers.

Physical therapy includes strengthening of the periscapular muscles and internal and external rotators and stretching to prevent stiffness and further loss of motion.

Cortisone injection: Forty to 80 mg triamcinolone with 5 to 10 mL 1% Xylocaine is placed in the subacromial-glenohumeral space to decrease synovitis and bursitis, improve pain, and facilitate physical therapy.

Activity and expectation modification: The physician should explain avoidance of inciting activities that increase pain and discuss realistic functional goals for patients with irreparable cuff tears.

INDICATIONS FOR LATISSIMUS DORSI OR COMBINED LATISSIMUS DORSI AND TERES MINOR TENDON TRANSFERS

The treatment decisions regarding management of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears must be made in the context of the patient’s current functional deficits, level of pain and its suspected cause, and physical examination findings.

What the patient should expect in terms of postoperative pain relief and functional improvement must be clearly delineated before surgery. Return of full (normal) strength,

active range of motion, and complete resolution of pain are not realistic goals for most patients with large irreparable rotator cuff tears, regardless of the surgical treatment option selected.

Table 1 Prognostic Factors for Superior Latissimus Dorsi Transfers

Parameter

Better Prognosis

Worse Prognosis

Age

<60 y

>60 y

Gender

Male

Female

Function

Chest level or better

Below chest level

Subscapularis condition

Intact, functional

Torn, dysfunctional

Deltoid condition

Intact

Detached, dysfunctional

Previous surgery

No

Yes

Superior tendon transfer to the humeral head for isolated irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tear

Only a carefully selected subset of patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears are good candidates for superior latissimus/teres tendon transfers.

Ideal patients are younger and have good deltoid and subscapularis muscle strength, limited glenohumeral arthritis, and the ability to get shoulder-level active forward flexion preoperatively.

Table 1 lists specific prognostic factors for success with superior tendon transfer.

Lateral tendon transfer to the proximal humerus (L’Episcopo technique) in association with reverse shoulder arthroplasty for combined posterosuperior rotator cuff tear and cuff tear arthropathy

Lateral tendon transfers combined with reverse shoulder arthroplasty are reserved for patients who are otherwise good candidates for reverse shoulder arthroplasty but also demonstrate preoperative external rotation lag signs and the inability to actively maintain greater than 0 degree of external rotation.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT: OPEN SURGICAL APPROACH FOR SUPERIOR TRANSFER OF THE LATISSIMUS DORSI/TERES MINOR

Preoperative Planning

An estimate should be made of the likelihood of successful primary repair based on the degree of cuff retraction and tissue quality.

The equipment needed for both an attempted cuff repair and for muscle transfer should be available at the time of surgery.

The possibility of needing to use autograft or allograft tendon to augment the length of the latissimus dorsi transfer should be discussed with the patient and the site for autograft harvest must be draped appropriately at the time of surgery, or allograft tissue must be available.

Positioning

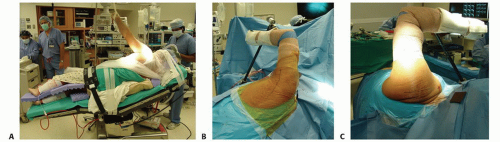

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position and secured with a beanbag or hip positioner posts (FIG 5A).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree