Latissimus Dorsi Transfers in Rotator Cuff Reconstruction and in Combination with the Reverse Total Shoulder Prosthesis

Lawrence V. Gulotta

Christian Gerber

ISOLATED LATISSIMUS DORSI TRANSFER FOR MASSIVE, IRREPARABLE ROTATOR CUFF TEARS

Indications/Contraindications

While there is no universally accepted definition of a “massive rotator cuff tear,” we refer to this term if the tear involves disinsertion of no less than two complete tendons (1, 2). This is a more anatomic definition than documenting the dimensions of a defect. It should be understood, however, that not only the size of the tendon defect but also the quality of the musculotendinous tissue are important variables for reparability. Three distinct patterns of massive rotator cuff tears are recognized: posterosuperior, anterosuperior, and global configurations. Posterosuperior rotator cuff tears are the most common type and involve the supraspinatus and infraspinatus (and frequently, the teres minor) tendons.

Although most rotator cuff tears can be repaired successfully, the overall size of the musculotendinous defect, fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff muscles, static superior subluxation of the humeral head, and poorquality tendon/bone may prevent successful repair. In such cases, alternative reconstructive surgical techniques are considered (3).

Historically, the management of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears encompasses a wide range of surgical solutions including open/arthroscopic débridement, local tendon transposition (upper subscapularis,

teres minor, teres major), extrinsic tendon transfer (trapezius), tendon autografts and allografts, synthetic graft material, and deltoid flap reconstruction. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer, as described in 1988 by Gerber et al. (3), is our preferred method for the management of the pain and functional deficit caused by irreparable, massive, posterosuperior rotator cuff tears in individuals with high functional demands. By replacing an irrecoverable musculotendinous cuff unit with healthy extrinsic substitute, this technique alleviates pain and improves function by restoring active external rotation to the glenohumeral joint (3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

teres minor, teres major), extrinsic tendon transfer (trapezius), tendon autografts and allografts, synthetic graft material, and deltoid flap reconstruction. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer, as described in 1988 by Gerber et al. (3), is our preferred method for the management of the pain and functional deficit caused by irreparable, massive, posterosuperior rotator cuff tears in individuals with high functional demands. By replacing an irrecoverable musculotendinous cuff unit with healthy extrinsic substitute, this technique alleviates pain and improves function by restoring active external rotation to the glenohumeral joint (3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

Indications

The main indication for latissimus dorsi tendon transfer is an irreparable, massive, posterosuperior rotator cuff tear in a patient with intolerable shoulder pain and subjectively unacceptable dysfunction (3, 4, 5, 6, 7). Most important is the potential to restore functional active external rotation.

Prior to surgical intervention, it is possible to predict those patients in whom direct, primary repair of a rotator cuff tear is likely to fail (8). Profound weakness of external rotation (both in abduction and adduction), external rotation “lag sign” of more than 30 degrees, superior migration of the humeral head with acromiohumeral distance (ACHD) less than 7 mm, long duration of tendon tear, and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence of grade 2 (or worse) fatty replacement of the rotator cuff muscles are all harbingers of unsuccessful rotator cuff repair. This constellation of findings, however, in a patient with shoulder pain and dysfunction highlights the precise indications for latissimus dorsi transfer.

A positive external rotation lag sign provides valuable insight into the specific anatomic areas of the rotator cuff tear. A patient with active external rotation lag with the arm at the side has a massive rotator cuff tear involving the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. Active external rotation lag in abduction signifies extension of the tear into the teres minor. This loss of external rotation can successfully be addressed with latissimus dorsi transfer. While combined loss of active external rotation and elevation may be an indication for latissimus transfer in a young, active patient, isolated loss of elevation cannot consistently be recovered. Patients with static superior subluxation of the humeral head with an ACHD of less than 7 mm fare just as well after latissimus transfer as those without superior humeral head subluxation.

The optimal indication for this procedure is a patient with a painful shoulder, preserved anterior elevation, and negative “lift-off” sign but with positive “external rotation lag” and “hornblower” signs.

Contraindications

The mere presence of a massive rotator cuff tear does not necessarily indicate the need for rotator cuff reconstruction with latissimus dorsi transfer. Some patients with massive cuff tears experience minimal pain and maintain good overall shoulder function. Reconstructive surgery in such patients is unnecessary. Patients with anterosuperior rotator cuff tears, which involve the subscapularis such that the lift-off test is positive, are not good candidates for latissimus dorsi transfers (3, 5, 6). A torn subscapularis is a contraindication for transfer.

Prior failed attempts at primary rotator cuff repair are not necessarily contraindications to subsequent latissimus transfers, but as documented by Warner and Parsons (9), salvage reconstruction of failed prior rotator cuff repairs yields more limited gains in satisfaction and function than primary latissimus dorsi transfers. Other relative contraindications include deltoid dysfunction and shoulder stiffness (3, 5, 6, 8, 9).

Preoperative Planning

History

The history and physical examination are the diagnostic cornerstones of the massive, irreparable, posterosuperior rotator cuff tear. Clues to the size of the tendon(s) tear and the quality of the tendon tissue can be expected from the history given by the patient (8). Atraumatic and insidious onset of pain and loss of function over the course of months or years suggest poor tendon quality as well as atrophy and fatty infiltration of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle bellies.

Often, the chief complaint is fatigue, especially when using the arm with the shoulder abducted. A frequent scenario is problems when dining because the patient cannot maintain external rotation with the arm at the side. Inability to maintain external rotation forces the patient to compensate by abducting the shoulder, which, in turn, encroaches on the adjacent person at the table.

Physical Examination

We begin the physical examination of the shoulder with inspection of the ipsilateral and contralateral shoulders for signs of prior trauma/surgery, atrophy, and deformity. Deformity consistent with static anterosuperior subluxation is an indicator of anterosuperior rotator cuff tear, a contraindication for latissimus dorsi transfer. Furthermore, deltoid defects should be examined closely and interpreted correctly, because they may constitute contraindications for this procedure. Atrophy of the spinati musculature is often readily apparent in patients with long-standing massive rotator cuff tears but is more commonly an indicator that rotator cuff repair is not possible. However, spinati atrophy does not constitute a contraindication for latissimus transfer.

Next, we passively assess and document range of motion in elevation, abduction, and internal and external rotation. In our experience, the shoulder must be passively supple for latissimus transfer to be successful.

Conversely, loss of passive range of motion constitutes a contraindication for this procedure. The only exception is diminished internal rotation of three to four vertebral levels compared with that of the contralateral side. Internal rotation loss of such a minor degree should not affect successful outcome.

Conversely, loss of passive range of motion constitutes a contraindication for this procedure. The only exception is diminished internal rotation of three to four vertebral levels compared with that of the contralateral side. Internal rotation loss of such a minor degree should not affect successful outcome.

Next, active range of motion is assessed using a goniometer with the patient seated. We document active elevation in the scapular plane and abduction and internal and external rotation at the side and in abduction. Loss of active elevation over 90 degrees, also termed pseudoparalysis, is a contraindication to latissimus transfer if it is clearly associated with anterosuperior dynamic subluxation of the humeral head.

A critical physical examination finding is discrepancy between passive and active motion arcs. The external rotation lag sign is highly suggestive of a massive rotator cuff tear with grade 3 fatty infiltration of the infraspinatus. Such a rotator cuff tear is irreparable and amenable to latissimus dorsi transfer. Note that in the presence of subscapularis insufficiency (i.e., positive lift-off test), external rotation lag sign may, in fact, be due to testing the shoulder in hyperexternal rotation and not because of infraspinatus weakness. In such a situation with subscapularis insufficiency, latissimus dorsi transfer is contraindicated. Several physical examination findings are specific for massive, posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. In addition to the previously described external rotation lag sign, the hornblower sign is pathognomonic for a massive rotator cuff tear involving the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor (3, 5).

After full documentation of active and passive range of motion, formally assess rotator cuff strength. Whereas for purely clinical purposes, manual muscle testing may be acceptable, instrumented strength measurement is mandatory for scientific purposes. Strength in abduction, “empty can” elevation, and internal and external rotation with the arm in adduction and abduction are documented. The lift-off and “belly press” tests for subscapularis competence should be performed. The lift-off test must be negative or exhibit only a trace amount of internal rotation lag to consider latissimus dorsi transfer. If passive internal rotation is limited, the belly press test should be used to assess subscapularis function.

Pain can interfere with the accurate assessment of range of motion and strength testing. Specifically, if the patient cannot elevate the arm above the head and it is unclear whether this is due to pain or a structurally based functional compromise, we perform a subacromial impingement test by injecting 15 mL of 1% lidocaine into the subacromial space prior to examining the patient. This intervention will alleviate pain and identify whether the patient is able to actively elevate the arm or at least to maintain the arm above the head if it is lifted into this position.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies provide important information in the diagnosis and appropriate management of irreparable, massive posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Our standard plain radiograph protocol includes a true anteroposterior (AP) of the shoulder, an axillary view, and supraspinatus outlet views (2). In the context of massive rotator cuff tears, the true AP of the shoulder is best to demonstrate superior migration of the humeral head and to measure the ACHD. The normal ACHD averages 10.5 mm. Patients with rotator cuff tears have an average ACHD of 8.2 mm. A value of 7 mm or less suggests an irreparable tear of the infraspinatus and is a strong indicator to consider a latissimus dorsi transfer rather than repair if the clinical findings are compatible with such a procedure. The axillary radiograph is obtained specifically to demonstrate the presence of an os acromiale, which is more prevalent in the rotator cuff tear population.

As described previously, muscle quality is at least as important as cuff defect size when deciding between an attempt at primary rotator cuff repair and a latissimus dorsi transfer. In this context, CT scanning has proven to be an invaluable tool (10). More recently, CT has been gradually superseded by MRI, which in our institution is currently the standard for assessment of muscle quality (11). We perform MRI scans on all patients clinically suspected of having a massive rotator cuff tear. The benefit of MRI is not in the diagnosis of the tear itself but, rather, in providing critical information about the degree of muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration in the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle bellies. Because several authors have demonstrated that chronic muscle infiltration does not recover after surgical repair, advanced fatty infiltration constitutes an important hallmark for irreparability (6). We document the degree of fatty replacement according to the grading system proposed by Goutallier et al. (10) and adapted for MRI by Fuchs et al. (11). For our purposes, the oblique sagittal images are the most useful in this regard. We indicate on the MRI requisition the specific reason for obtaining the study (i.e., evaluation of the rotator cuff muscle quality) and insist that the imaging sequences include the entire scapula up to its medial border.

Surgery

Anesthesia/Analgesia Management

Complete intraoperative and perioperative analgesia/anesthesia is critical to the overall success of latissimus dorsi transfers for massive, posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Because there are two operative fields that are extensive in overall size, general endotracheal anesthesia is required. However, to provide postoperative relief of pain, an anesthesiologist familiar with regional anesthesia, specifically interscalene block and catheterization, evaluates all of our patients preoperatively.

Preoperatively, the anesthesiologist prepares for an interscalene block by placing an indwelling interscalene catheter using electrostimulation technique. During the operative procedure, however, general endotracheal anesthesia is used. Postoperatively, careful neurologic examination of the upper extremity is performed. If the patient’s neurologic examination is normal, the interscalene block is activated in order to provide optimal postoperative pain control.

Patient Positioning and Draping

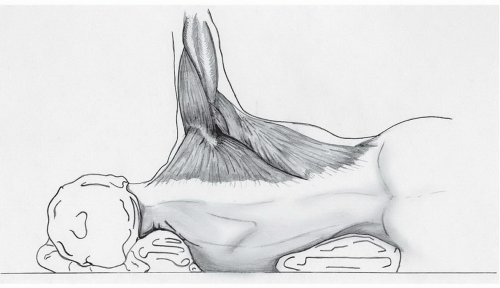

We perform latissimus dorsi transfer for reconstruction of massive, posterosuperior rotator cuff tears in the lateral decubitus position with the trunk elevated into a slight beach-chair position (Fig. 28-1). The patient is positioned as far laterally on the operating table as possible to facilitate optimal positioning for the surgeon. A full-length beanbag is used to support the entire body. An axillary roll is placed beneath the contralateral side and all bony prominences are padded. We mold/contour the full-length beanbag so that it cradles the entire torso in a stable position, ensuring that the beanbag does not encroach on the posterior surgical field.

This procedure requires two separate surgical approaches, anterosuperior and posteroinferior. Therefore, we prepare the entire upper extremity and hemitorso in a sterile fashion such that the ipsilateral neck, back, chest, and upper extremity will be in the operative field after draping.

The surgeon and the first assistant stand behind the patient during the procedure. Across the operative field, the second assistant stands in front of the patient and maintains the position of the arm and shoulder during the procedure.

Antibiotic prophylaxis with 2 g of cefazolin is administered intravenously during draping.

Technique

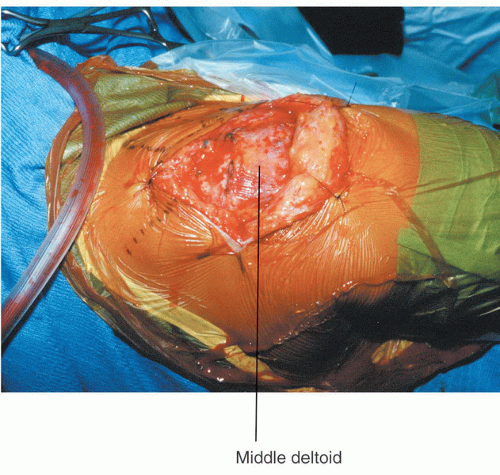

After prepping and draping, the arm is placed at the side and the bony landmarks of the shoulder are palpated and outlined, including the acromion, acromioclavicular joint, clavicle, and coracoid process. Next, the desired lines of incision for both the rotator cuff exposure and the latissimus dorsi harvest are marked. For the anterosuperior exposure, we draw a straight line over the lateral one-third of the acromion parallel to Langer lines. It begins at the posterolateral edge of the acromion and extends anteriorly to 2 to 3 cm lateral to the coracoid process (Fig. 28-2). For the posteroinferior exposure, we draw a line following the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi (or the posterior axillary fold), which curves anteriorly to the anterior inner third of the humerus about 4 cm proximal to the axillary fold (Fig. 28-3). Prior to incising the skin, we use impermeable, bacteriocide-impregnated drapes to cover all exposed skin.

FIGURE 28-4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|