Lateral Epicondylitis

Jack E. Kazanjian

Charles L. Getz

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Lateral epicondylitis affects 1% to 3% of adults each year. Runge first described lateral epicondylitis as “writer’s cramp” in 1873 in the German literature, and it was named “lawntennis arm” by Major in 1883 due to its association with the sport. Over the years, the condition earned the moniker “tennis elbow,” based on its observed prevalence in racquet sport participants. While up to 50% of all recreational tennis players will experience symptoms of lateral epicondylitis at some point, these individuals make up only 5% to 10% of the overall patient population with tennis elbow. Patients with lateral epicondylitis often complain of diffuse lateral elbow pain of insidious onset. The patient may identify an injury or moment in time when the pain began. More commonly, there is no inciting event, and the pain has progressively worsened over time. The patient often describes worsening pain with repetitive tasks, especially those involving wrist extension and lifting. Radiating pain down the distal forearm often accompanies the proximal elbow pain. The degree of discomfort can range from the occasional activity related dull ache to a constant, debilitating pain that is present even at rest. Occupations such as plumbing, meat cutting, and painting that involve repetitive motions are often seen in this patient population.

It is important for the physician to elicit any confounding aspects of the patient’s history in order to identify conditions that may present similarly to lateral epicondylitis (Table 43-1). A history of neck pain or upper extremity numbness may indicate underlying cervical radiculopathy or posterior interosseous nerve compression. Complaints of persistent elbow stiffness are present in posttraumatic or primary elbow arthritis (although morning stiffness is a common complaint with tennis elbow). Histories of clicking, locking, or giving way are often components of chronic elbow instability. Finally, fracture about the elbow is possible with new-onset pain and recent injury.

Nirschl1 described specific risk factors for developing lateral epicondylitis. These include age >35 years, high-demand work or sport activities, and poor general fitness level. While tennis elbow patients can range in age from 12 to 80 years, the characteristic patient with lateral epicondylitis is an adult in the fourth or fifth decade of life. Men and women are equally affected, with symptoms more commonly seen in the dominant arm. Risk factors include a history of manual labor with heavy tools and significant strain while performing repetitive tasks. Pain in tennis players is secondary to factors such as poor technique, improper racquet or grip size, extensive playing time, and use of a one-handed backhand stroke.2

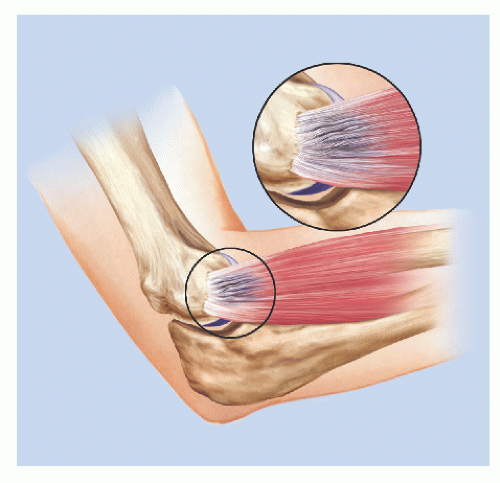

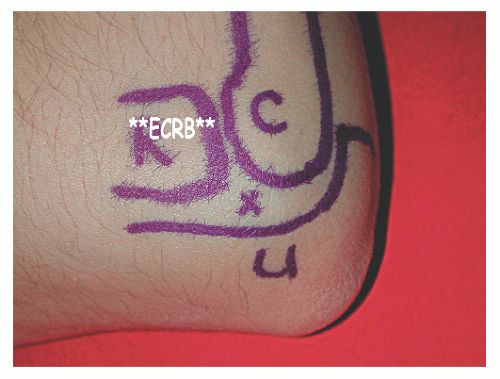

The common extensor origin arises from the lateral epicondyle, and its muscles insert distally to extend the wrist and fingers. The muscles that make up this area include the extensor carpi radialis longus, the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), the extensor digitorum communis (EDC), and the extensor carpi ulnaris. The primary tendon origin involved in lateral epicondylitis is the ECRB, with the EDC involved in approximately one-third of patients.1,2

TABLE 43-1 Differential Diagnosis of Lateral Epicondylitis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CLINICAL POINTS

Repetitive tasks involving the wrist frequently make pain worse.

Pain may be related to activity (e.g., tennis) or occur at rest.

Consideration of patient history allows identification of similar conditions.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The goal of the physical examination of a patient with suspected lateral epicondylitis is to identify the location of maximal tenderness through palpation and provocative tests. The main complaint of these patients is lateral elbow pain, which can be constant or activity related based on the disease severity. While the focus of the physical examination is the painful elbow, the physician must also evaluate the entire limb as well starting at the cervical spine. A Spurling test (axial compression applied to the extended neck deviated to the affected side) can elicit signs of C6-7 nerve root compression with radicular pain in that dermatome. Deep tendon reflexes are evaluated and compared with the opposite side. Strength testing of the entire limb is important to rule out both compressive neuropathy and possible rotator cuff pathology. Particular attention is paid to the presence of rotator cuff atrophy along the scapula. This can contribute to worsening lateral tendinosis and may require concomitant rehabilitation during treatment. Limited shoulder internal rotation can be a culprit in lateral epicondylitis and should be checked for and addressed appropriately in prescribing a rehab program.3

When specifically addressing the elbow, the examiner should evaluate range of motion, including rotation, and compare results with the opposite side. Palpate the posterolateral soft spot of the elbow to evaluate for a ballottable effusion. This finding, along with crepitus on range of motion, suggests possible osteochondral injury and should be correlated with a history of injury. When this portion of the examination is complete, the physician can focus on findings specific to lateral epicondylitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree