Lateral Collateral Ligament Reconstruction of the Elbow

Vikram Sathyendra

Anand M. Murthi

DEFINITION

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injuries most often occur after significant elbow trauma, most commonly after dislocation.

Attenuation of the LCL can also occur after multiple surgeries to the lateral side of the elbow and after corticosteroid injections.9 It has recently been reported that even one corticosteroid injection may result in lower complete recovery rates and in recurrence rates after 1 year.6

LCL attenuation has been reported to occur in patients who have residual cubitus varus after malunion of supracondylar humerus fractures.12

Significant injury to the LCL complex can result in posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI).

ANATOMY

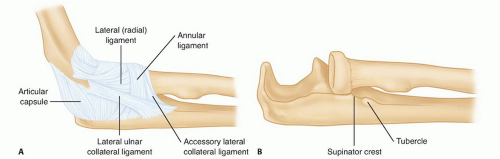

The LCL is made up of four major components: the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL), also called the radial ulnohumeral ligament (RUHL); the radial collateral ligament (RCL) proper; the annular ligament; and the accessory collateral ligament (FIG 1).

The ligaments originate from a broad band over the lateral epicondyle, deep to the extensor muscle mass, and separate distally into more discrete structures.

The RUHL is the most important stabilizer against PLRI, and it attaches distally on the supinator crest of the ulna.11

The supinator tubercle resides approximately 15 mm distal to the proximal border of the proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ).1

The RCL is more anterior and primarily resists varus stress.

The annular ligament sweeps around the radial head/neck and stabilizes the PRUJ.

The capsule acts as a static stabilizer, especially at the anterior portion, while the arm is extended.

The anconeus and extensor muscle groups act as dynamic stabilizers.

On average, the posterior interosseous nerve crosses the midpoint of the radius 33.4 ± 5.7 mm with the forearm in supination. This distance increases to 52.0 ± 7.8 mm with the forearm in full pronation, thereby increasing the safe zone for exposure of the lateral elbow.7

PATHOGENESIS

Multiple studies have shown that injury to the LCL can lead to PLRI, which is the first stage in elbow instability that can lead to frank elbow dislocation.

It is controversial whether injury to the RUHL alone can lead to PLRI or whether further injury to the LCL complex is necessary.10

When the forearm is supinated and slightly flexed, a valgus stress with an attenuated LCL causes the ulnohumeral joint to rotate, compresses the radiocapitellar joint, and ultimately causes the radial head to subluxate or dislocate posteriorly from the ulnohumeral joint.

NATURAL HISTORY

PLRI is not a new condition, but it has only recently been described and studied.

The prevalence and natural history of this condition are currently not known.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients typically report trauma but may have had recurrent lateral epicondylitis or previous surgery.

Elderly patients may not have frank dislocation of the elbow, but 75% of patients younger than 20 years report an elbow dislocation.10

Patients typically report mechanical-type symptoms (clicking, popping, and slipping) during elbow supination and extension and rarely report recurrent dislocations. These symptoms may impact activities such as pushing up from a chair with the arms or doing pushups.

Physical examination can be difficult; provocative tests are described in the following text. It is often necessary to conduct these tests with the patient under anesthesia or with the aid of fluoroscopy.

Inspection for effusion: With acute injuries, lateral gutter soft spot effusion is likely to be present, but in more chronic situations, it may be absent.

Range of motion (ROM): Locking of the elbow can represent loose bodies; stiffness may indicate intrinsic capsular contracture.

Supine lateral pivot shift test: When the elbow is slightly flexed, the radial head can be palpated to subluxate or frankly dislocate, and as the elbow flexes past 40 degrees, it relocates, often with a palpable clunk.11 This test is often difficult to perform on an awake patient because apprehension is felt and the patient does not allow the test to continue.

Prone pivot shift test: Radial head or ulnohumeral subluxation constitutes a positive test, same as the supine lateral pivot shift test. Examination under anesthesia may be required.

Push-up test: Reproduction of the patient’s symptoms of apprehension during supination and not pronation constitutes a positive test. Inability to complete the push-up also constitutes a positive test.

Chair push-up: Elicited pain constitutes a positive test.

Table top relocation test: Elicited pain or apprehension as the elbow reaches 40 degrees constitutes a positive test.

Elbow drawer test: Ulnohumeral subluxation constitutes a positive test.

A thorough examination of the elbow should also be completed to rule out other injuries.

Valgus instability with the forearm in pronation and 30 degrees of flexion suggests medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury.

Lateral epicondylitis or radial tunnel syndrome can present with tenderness over the proximal extensor mass and with resisted extension of the wrist (Thompson test) and long finger.

Loose bodies may present with crepitus or locking of the elbow during ROM.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

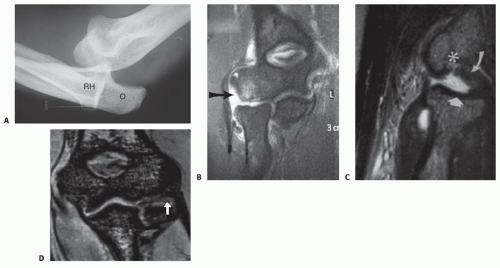

Standard anteroposterior (AP) and lateral view radiographs often indicate normal findings but may reveal small lateral epicondyle avulsion fractures and radiocapitellar wear.

Stress AP and lateral view radiographs may reveal widening of the ulnohumeral joint and posterior subluxation of the radial head (FIG 2A).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), especially with intra-articular contrast enhancement, may reveal injuries to the LCL complex. The proximal extensor mass requires attention (FIG 2B). Chronic PLRI may lead to evidence of a posterolateral osteochondral defect coined the Osborne-Cotterill lesion (FIG 2C,D).8

Diagnostic arthroscopy of the elbow can be performed, although we do not recommend routine diagnostic arthroscopy for this injury.

The drive-through sign occurs when the scope can easily be “driven through” the lateral gutter into the ulnohumeral joint from the posterolateral portal.

The pivot shift test also can be performed during arthroscopy, and the radial head will subluxate posteriorly.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Lateral epicondylitis

Extensor tendon tear

Loose bodies

Elbow fracture-dislocation

MCL injury

Radial head dislocation

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

If the injury is diagnosed early, immobilization in a hinged elbow brace in pronation for 4 to 6 weeks may prevent chronic instability.5

Removable neoprene sleeves may offer support.

A trial of elbow extensor strengthening with progressive ROM can be performed.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications

Recurrent symptomatic PLRI despite nonoperative treatment

Preoperative Planning

All imaging studies should be reviewed, and informed consent obtained.

An examination of the elbow should be performed with the patient under anesthesia, especially the pivot shift test.

If there is any doubt regarding the diagnosis, a pivot shift test should be performed under fluoroscopy.

Positioning

The patient is placed supine on the operating room table.

The arm can be placed on an arm board or across the patient’s chest with a sterile tourniquet applied to the upper arm and the entire arm draped free (FIG 3).

During the approach, the forearm should be pronated to protect the posterior interosseous nerve.