Knee Rehabilitation

Brian J. Eckenrode

Christopher J. Kauffman

The knee joint is the primary functional link of the lower extremity, which is essential for mobility and stability of the leg for activities such as ambulation, stair-climbing, transfers, and high-level activities. The typical clinical presentation to the primary care physician usually involves complaints of knee pain and/or swelling with self-reported decreased functional activities.1,2,3,4 Loss of knee range of motion (ROM), decreased strength, joint instability, and mechanical symptoms may also be present, contributing to diminished function. Proximal and distal impairments can also contribute to knee dysfunction5,6,7,8 and should also be examined.

The restoration of function and improvement in the patient’s quality of life is the primary goal for rehabilitation. Management of knee pain is essential for controlling symptoms and allowing for an optimal tissue healing environment. Conservative nonpharmacologic management of pain includes physical therapy, patient education on the use of thermal modalities, rest from aggravating activities, assistive device utilization (see Fig. 74-1), weight loss information, and knee bracing/taping can aid in controlling symptoms.

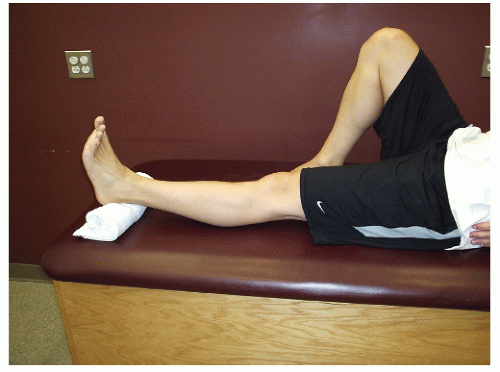

Full knee flexion and extension ROM is necessary for normal function of the lower extremity. The importance of full, symmetrical knee extension ROM cannot be overstressed, as mild extension loss can have a significant impact on knee pain and gait.9 To address any loss of knee extension ROM, the application of a low-load, long-duration stretch can be performed with a heel prop (Fig. 75-1). The patient is instructed to place a rolled-up towel under the heel in the supine position for 5 to 10 minutes, three to five times per day until symmetrical extension motion is achieved. The application of moist heat to the knee can also assist in patient relaxation during this exercise. To address any loss of knee flexion ROM, the heel slide exercise can be utilized (Fig. 75-2). Have the patient place a towel or sheet around the ankle in the long sitting position. The patient is instructed to slide the heel toward the buttocks by pulling on the ends of the towel or sheet until mild stretch is perceived. Have the patient maintain this stretched position for 10 to 15 seconds for ten repetitions three to five times per day.

Flexibility exercises can assist in restoring normal joint motion.10 Increasing lower extremity flexibility and ROM allows for improved cartilage nutrition and health, protection of joint structures from damaging impact loads, and enhanced function and comfort in daily activities.11,12 The quadriceps muscle, which crosses both the hip and knee joint, can be stretched with the patient in prone with a sheet or strap around the involved ankle (Fig. 75-3). Have the patient pull the opposite end of the sheet or strap with the knee moving into increasing flexion until a stretch is perceived in the anterior thigh musculature. To stretch the hamstrings, the patient is supine with the hands holding the involved hip and knee at 90 degrees (Fig. 75-4). The patient then attempts to actively extend the knee until resistance is perceived in the posterior thigh. It is recommended that both of these stretching techniques be held for 30 to 45 seconds, three repetitions each for two times per day on an ongoing basis.

Weakness of the musculature of the knee and hip has been associated with multiple pathologies affecting the knee including osteoarthritis,13 anterior cruciate ligament injury,14 and patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS).14 Often nonweightbearing strengthening exercises are safe to initiate in patients with lower extremity weakness as this will minimize joint reaction forces at the knee. Isometric quadriceps setting is a simple and effective method to initiate quadriceps activation. The patient is in supine with the knee extended, and they are instructed to contract the quadriceps muscle by pressing the back of the knee down into while simultaneously attempting to lift the heel off the surface (Fig. 75-5). The patella should glide superiorly during the contraction, and the hip extensor muscles should remain relaxed. The straight-leg raise exercise has been shown to activate the quadriceps without irritating the tibiofemoral or patellofemoral joint.15 The patient is instructed to flex the knee of the uninvolved leg to 90 degrees while keeping the involved knee in extension while lifting from the hip to the height of the opposite knee and held for 3 seconds then lowered (Fig. 75-6). It is recommended that patients perform 1 to 3 sets of 10 to 12 repetitions to fatigue for 2 to 3 times per week. It is advised that strengthening

exercises be performed on nonconsecutive days and resistance should be progressed as able to maximize strength gains.

exercises be performed on nonconsecutive days and resistance should be progressed as able to maximize strength gains.

For patients with mild symptoms, minimal joint reactivity, and minimal difficulty with the straight-leg raise exercise, the patient can progress to weightbearing exercises with ongoing symptom monitoring. The mini-squat (Fig. 75-7) facilitates symmetrical weightbearing between the legs, reduces shear forces across the tibiofemoral joint, minimizes patellofemoral compressive forces, and enhances co-contraction of the quadriceps and hamstrings.16,17,18 The mini-squat should be performed to 45 degrees of knee flexion and follows the strengthening principles as noted above.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree