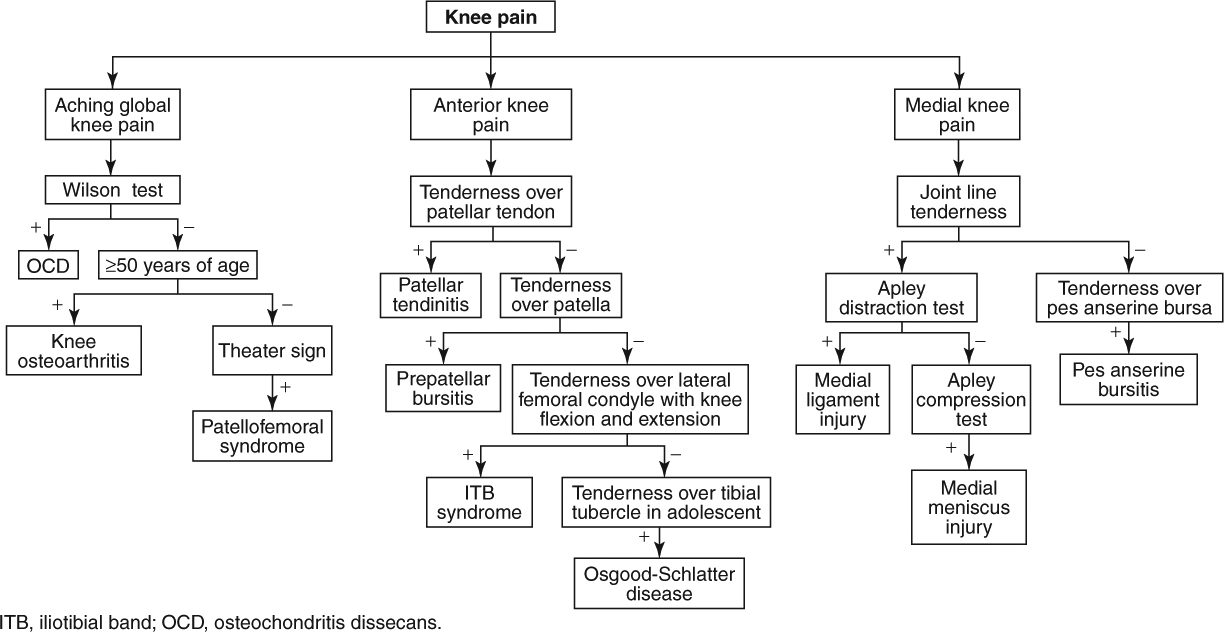

Knee Pain

|

Red Flag Signs and Symptoms

Any of these signs and symptoms should prompt urgent evaluation and appropriate intervention:

Fevers

Chills

Hot, swollen joint

Progressive neurologic symptoms

Loss of pulses

KNEE OSTEOARTHRITIS

Background

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a very common cause of knee pain, particularly in patients older than 55 years with knee pain. The prevalence increases with increasing age. The medial compartment (including the medial tibial plateau and medial femoral condyle) of the knee is most often affected. Obesity, history of knee injury, and quadriceps weakness all increase the likelihood of developing knee OA.

Clinical Presentation

Patients are typically older than 55 years and complain of insidious onset of knee pain. The medial side, or anterior and medial side, of the knee may be most painful; however, the whole knee is also often painful. The pain is often described as dull and aching. Initially, the pain is present only with activities such as ascending and descending stairs (particularly going down stairs).

As the disease progresses, the pain becomes present with less strenuous activities such as walking long distances. The knee also becomes stiff and the patient may note that it swells up after use. Patients may report that it takes “a little while to get going” after standing up and walking or after waking up in the morning. As the patient walks, the knee warms up and feels better. However, if the patient walks “too much,” the pain is exacerbated and limits walking.

Patients may also complain of locking, catching, or stiffness, particularly after prolonged sitting.

As the disease becomes more severe, pain may be present at night or even wake the patient from sleep.

Physical Examination

The patient may have an antalgic gait, favoring the asymptomatic side. A mild effusion may be present, although a hot and swollen knee should raise suspicion for a septic knee. Crepitus may be noted with passive extension and flexion of the knee. The joint line may be tender. However, there is not typically one tender point that reproduces the patient’s symptoms. Rather, knee OA produces more diffuse symptoms than that. Comparison with the asymptomatic side may reveal mild quadriceps atrophy.

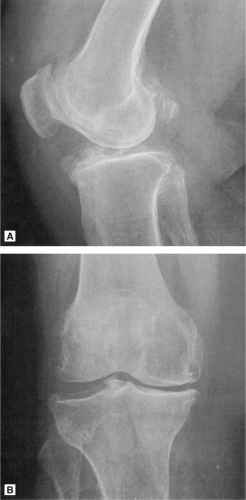

Diagnostic Studies

Radiographs should be obtained (Fig. 7.1). Importantly, severity of OA on radiograph does not necessarily correlate with degree of symptoms. Characteristic findings include asymmetric joint space narrowing, osteophytes, subchondral cysts, and other findings of OA. Medial joint line often reveals most of the OA; however, a tunnel view may also reveal osteophytes and other OA findings. The lateral side often has findings of OA but not as pronounced as the medial side.

If a septic knee is suspected, arthrocentesis should be performed and the appropriate labs (cell count, crystals, glucose, Gram stain, culture, protein) sent.

Treatment

The cornerstone of treatment, physical therapy that emphasizes strengthening of the quadriceps, should be started. Closed-chain exercises (foot is fixed, as in a leg press) may be preferable for this purpose because they have less sheer forces than open-chain exercises (foot is not fixed, as in knee extension). Gait biomechanics should also be addressed with therapy.

Importantly, the patient needs to continue to be active. Once the knee is painful, the tendency is to stay off the knee. However, in OA, the cartilage is degraded. To continue to provide nourishment to the remaining cartilage, weightbearing and movement are essential. If the patient

stays off the painful extremity, the remaining cartilage quickly erodes and the process is very hard to address nonsurgically. Of course, the patient should not work through too much pain. A healthy balance must be reached.

stays off the painful extremity, the remaining cartilage quickly erodes and the process is very hard to address nonsurgically. Of course, the patient should not work through too much pain. A healthy balance must be reached.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen may be helpful as pain relievers.

Oral supplementation with glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate may also be helpful, although more research is needed to make definitive recommendations. An advantage of these supplements is that they appear to not have the same negative side-effect profile as NSAIDs.

An intra-articular injection of steroid and anesthetic is very helpful in reducing symptoms (Fig. 7.2). This is often done blind, although it can also be done under ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance to ensure optimal placement. These injections typically provide 4 months to 1 year of relief. They may be repeated up to three times yearly as needed. As the disease progresses, the steroid injections tend to become less effective.

INTRA-ARTICULAR KNEE INJECTION

There are multiple approaches to the knee joint. An intra-articular injection can be performed via lateral, inferolateral, inferomedial, superolateral, or superomedial routes. Every knee is different, and some knees may predispose to being injected from different directions depending on the anatomy. In general, the authors of this book favor an inferomedial approach.

Informed consent is first obtained. The patient lies supine with the knee flexed to about 30 to 45 degrees so the foot is flat on the examination table. The physician runs hands superiorly along the tibia until the fingers fall off the tibial plateau on the medial side of the patella. This point is marked. The authors favor using a 25-gauge, 1.5 inch needle, 40 mg of triamcinolone acetate, and 4 mL of 1% lidocaine. Sterilize the marked spot using three iodine swabs and an alcohol pad. Using sterile technique, aim the needle parallel to the ground directly into the joint. Straight ahead, the needle runs into the femoral condyle. Gently touch bone and then back off the bone. Always aspirate before injecting. If blood is found in the aspirate, reposition. There should be no aspirate in this injection. If an effusion is present in the knee, then an aspiration should be done first. See the next paragraph for details on how to perform an aspiration. When there is no aspirate and the injectate flows smoothly, inject. Clean the iodine off with alcohol pads.

If an effusion is present, it should be aspirated from the joint cavity. Aspiration helps provide symptom relief. There are multiple ways to approach aspiration. The one favored by the authors involves using a 22-gauge, 1.5 inch needle and inserting into the joint. For this injection, an anesthetic spray should be used. The joint is then aspirated. The syringe is switched with the needle still in the joint. The new syringe contains the injectate (40 mg of triamcinolone acetate and 4 mL of 1% lidocaine), which is injected. Extension tubing can be used to facilitate an easier transfer of syringes.

Intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid are also very effective for certain patients with knee OA. Ideally, these injections should be performed on patients with mild to moderate knee OA. They are less effective once the OA is severe. The hyaluronic acid injections are usually given once per week for 3 to 5 weeks depending on the preparation used. They may need to be repeated once every 6 months.

When aggressive conservative measures fail, several surgical options, including arthroscopy and osteotomy, are available. The most common and most effective surgical treatment is total knee arthroplasty. In the right patient population, this procedure greatly increases quality of life after surgery.

MENISCUS TEAR

Background

The menisci are fibrocartilaginous pads that serve as shock absorbers for the knee joint. The medial meniscus is more crescent shaped, and the lateral meniscus more circular. Only the periphery of the menisci (outer third) receives blood supply. A tear in this zone is said to be a “red” tear. A tear in the center two-thirds is said to be a “white” tear. Red tears are much more likely to heal with conservative care.

Clinical Presentation

Two typical types of patients present with meniscal tears: younger patients with acute pain and older patients with degenerative tears that occur gradually.

Younger patients are generally younger than 50 years. They report a history of an acute injury, such as a twisting injury with the knee in flexed position. This may occur, for example, during pivoting in basketball or soccer. Following the injury, patients report onset of pain, swelling, and/or stiffness. Sometimes, the pain begins immediately after the injury. Other times, the patient may not notice the pain

until later that night. Patients may complain of “locking,” or “catching.” Weightbearing, getting up from a seated position, and ascending stairs may exacerbate symptoms. Mild swelling generally occurs the day after the injury. Patients may localize their pain to the medial or lateral aspect of the knee. Occasionally, they may have difficulty identifying the exact location of their pain.

until later that night. Patients may complain of “locking,” or “catching.” Weightbearing, getting up from a seated position, and ascending stairs may exacerbate symptoms. Mild swelling generally occurs the day after the injury. Patients may localize their pain to the medial or lateral aspect of the knee. Occasionally, they may have difficulty identifying the exact location of their pain.

Older patients are generally older than 50 years. They typically present with an insidious onset of symptoms. Sometimes they recall a history of trauma to the knee (e.g., twisting). However, the injury does not immediately precipitate symptoms. Symptoms may include pain, locking, catching, and/or giving way.

Physical Examination

An effusion may be present on examination. Classic findings include joint line tenderness that reproduces the patient’s symptoms. The McMurray test and Apley compression and distraction test are very useful for assessing meniscal injuries. In the McMurray test (Fig. 7.3), the patient lies

supine with hip and knee fully flexed. The physician then externally rotates the tibia and applies a valgus force while extending the knee to assess the medial meniscus. To assess the lateral meniscus, the physician internally rotates the tibia and applies a varus force while extending the knee. A palpable snap or click is indicative of a meniscal tear.

supine with hip and knee fully flexed. The physician then externally rotates the tibia and applies a valgus force while extending the knee to assess the medial meniscus. To assess the lateral meniscus, the physician internally rotates the tibia and applies a varus force while extending the knee. A palpable snap or click is indicative of a meniscal tear.

In Apley’s compression and distraction test (Figs. 7.4A and B), the patient lies prone with the knee flexed to 90 degrees. The physician stabilizes the patient’s thigh with one hand and with the other hand internally and externally rotates the patient’s tibia while applying a compressive force (driving the patients tibia into the table). The physician then applies a traction force to the tibia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree