Knee Lateral Release

Andrea M. Spiker

Carl H. Wierks

Andrew J. Cosgarea

DEFINITION

Patellofemoral pain is a common symptom in active adolescents and adults.

The diagnosis of patellofemoral pain is nonspecific. It may be caused by trauma, instability, overuse, or anatomic abnormalities such as bipartite patella, maltracking, or malalignment. It may also be caused by a tight lateral retinaculum causing excessive compression of the patella on the lateral femoral trochlea.

The patella acts to enhance the extensor mechanism of the knee as it glides through its normal course within the femoral trochlea. Static bone and soft tissue stabilizers as well as dynamic muscular stabilizers maintain the patella within the femoral sulcus.18

The lateral retinaculum and patellofemoral ligament make up the lateral static soft tissue stabilizers of the patella. If these structures are abnormally tight, the patella can be excessively compressed against the femur with knee flexion, causing pain.18

This scenario of exaggerated patellar compression on the lateral femoral trochlea has been described as excessive lateral pressure syndrome (ELPS),10 patellar compression syndrome,18 and patellofemoral stress syndrome.25

This chapter describes lateral retinacular release of the knee, which is the surgical treatment for patients with ELPS who exhibit patellofemoral pain, a tight lateral retinaculum, and lateral patellar tilt. This surgical intervention is indicated for patients with ELPS only after nonoperative treatment has failed.

Lateral retinacular release has also been used to treat other patellofemoral disorders with varying success, including chondromalacia patellae, patella malalignment, and instability.2, 4, 8, 15, 20, 21, 22, 29 In this chapter, we will focus our discussion on ELPS, the most widely accepted indication for knee lateral retinacular release.

ANATOMY

The patella is a sesamoid bone that acts as a fulcrum in knee extension, providing a smooth surface over which the extensor mechanism can function while protecting the anterior knee.7

The patella also acts to centralize the converging forces of the four quadriceps muscles.

The thickest articular cartilage in the body is located in the patellofemoral joint.

Forces across the patellofemoral joint are approximately three times the body weight during ascending and descending stairs and can reach up to 20 times the body weight during activities such as jumping.1

As the knee flexes from full extension, the patella is drawn into the trochlear groove at approximately 20 degrees.

In extension, the medial patellofemoral ligament is the primary restraint to excessive lateral translation. As the knee flexes beyond 20 degrees, the lateral trochlear ridge becomes the primary restraint.

A tight lateral retinaculum and patellofemoral ligament may be responsible for excessively constricting the patella and causing symptoms of knee pain in patients with ELPS.

PATHOGENESIS

An abnormally tight lateral retinaculum can tether the patella against the lateral femoral trochlear during knee flexion, at which point patients may describe a sensation of pressure, grating, or symptoms of pain. With chronic excessive pressure, degeneration of articular cartilage in the lateral patellofemoral joint can occur.

Some conditions, such as a weak vastus medialis obliquus normal alignment (abnormal Q angle, lateralized tibial tuberosity, valgus deformity, internal tibial torsion, and femoral anteversion), predispose to lateral patellar tracking.

Direct trauma (eg, dashboard injury or patellar dislocation) can also result in degeneration of the lateral patellofemoral articular cartilage.

NATURAL HISTORY

No long-term natural history studies of ELPS have been reported to date.

It is well accepted, however, that disruption of articular cartilage results in progressive degenerative changes.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients typically report insidious onset of anterior knee pain that is activity related, although some may have a history of traumatic injury.

Pain is typically exacerbated by prolonged sitting, stair-climbing, or an increase in activity.

Symptoms and clinical findings of instability have no role in ELPS.

A thorough physical examination should include the following:

Examination for effusion. Effusion may indicate traumatic or degenerative disruption of the articular surface.

Observation of patellar tracking. A positive J sign, indicating patellar maltracking, occurs if the patella sits laterally in extension, then suddenly glides medially as it engages in the trochlear with flexion.

Patellar tilt test. The examiner attempts to lift the lateral border of the patella. If the lateral facet cannot be elevated to neutral, the lateral retinaculum is abnormally tight.

Patellar glide test. Patellar lateral glide of up to two to three quadrants is normal. Excessive lateral translation indicates incompetence of the medial retinaculum and the medial patellofemoral ligament. Comparison should be made to the contralateral leg.

Patellar apprehension test. As with the patellar glide test, examiner pushes the patella laterally. If the patient is apprehensive, it suggests that he or she is sensing patellar instability.

Examination of the quadriceps. Quadriceps tightness has been associated with patellofemoral pain. Quadriceps weakness, especially involving the vastus medialis, indicates a predisposition to instability.

Patellar grind test. With the knee in full extension, the examiner pushes directly down onto the patella, compressing it against the femoral sulcus. Pain may indicate patellofemoral arthritis but can also occur with normal articular surfaces.

Inspection for elevated Q angle. The Q angle is measured with the patient in a supine position as the angle formed by a line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the center of patella and a line from the center of the patella to the tibial tubercle. An angle of more than 15 to 20 degrees is abnormal and can predispose to lateral patellar subluxation.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiographs of the knee should include anteroposterior, tunnel, axial (sunrise), and 30-degree lateral views. If arthritis is suspected, a posteroanterior flexed 45-degree view should be obtained.

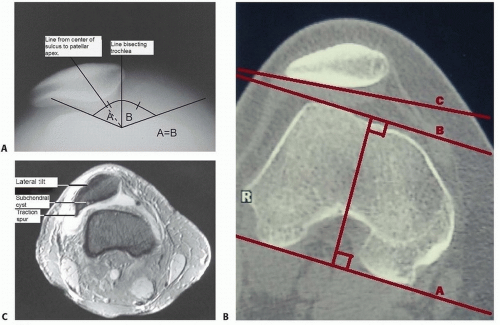

Lateral subluxation can be measured on the axial radiograph. If a line drawn from the patellar apex to the center of the trochlear sulcus is lateral to a line bisecting the trochlear sulcus angle, then the patella is subluxed laterally (FIG 1A). A computed tomography scan is the best way to evaluate patellar tilt radiographically. Using an axial image, a line is drawn along the posterior femoral condyles. This line is then compared to a line drawn along the lateral patellar facet. If these lines converge laterally, then the patella is determined to have excessive lateral tilt (FIG 1B).

A computed tomography scan can also be used to measure the tibial tubercle-trochlear groove (TT-TG) distance.

Magnetic resonance imaging may be beneficial in evaluating the integrity of articular cartilage and may also reveal concomitant meniscal and ligamentous pathology (FIG 1C).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Patellofemoral pain (without ELPS)

Patellar instability

Lateral meniscal tear

Patellar fracture

Iliotibial band syndrome

Prepatellar bursitis

Neuroma

Osteochondritis dissecans of the patella or trochlea

Bipartite patella

Patellofemoral arthritis

Medial patellar plicae6

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The mainstay of treatment is nonoperative, with the great majority of patients seeing improvement in patellofemoral knee pain after quadriceps stretching, strengthening, and physical therapy.12, 16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree