Abstract

Background

The cervical flexion–relaxation phenomenon (FRP) is a neck extensor myoelectric “silence” that occurs during complete cervical flexion. The aim of this study was to assess the presence of this phenomenon in the cervical region and to explore the kinematics and EMG parameters in two different experimental conditions.

Patients and methods

Nineteen young healthy adults (22.2 ± 2.4 years), without any cervical pain history, participated in this study and performed each of the experimental conditions. They had to accomplish a cervical flexion from a neutral seated position and from a 45° forward leaning seated position. Neck kinematics was assessed using a kinematic capture device in order to assess onset and cessation angle of the PFR. Cervical paraspinal and trapezius muscles EMG activities were also recorded. All data were compared in order to assess the differences between the two experimental conditions.

Results

Eighteen of the nineteen subjects showed a FRP. The phenomenon appears between 72.6 and 76.3% of maximal cervical flexion and disappears during the return to neutral position between 91.9 and 93.1% of maximal cervical flexion. The FRP was observed, at least unilaterally, in 84.2% (67.4% bilaterally) of tasks without forward bending of trunk, and 90.5% (79.0% bilaterally) of tasks with 45° forward bending of trunk. A significant increase in the flexion–relaxation ratio was observed in the 45° forward leaning condition. No significant difference could be observed between the two experimental conditions for the kinematics parameters.

Conclusion

The results of the present study indicate that cervical spine flexion in healthy subjects is characterized by a flexion–relaxation response. Moreover, the results indicate that trunk inclination might facilitate the evaluation of the cervical FRP.

Résumé

Introduction

Le phénomène de flexion–relaxation (PFR) cervical, à l’instar de la région lombaire, correspond à un « silence » myoélectrique des muscles extenseurs du cou lors de la flexion cervicale complète. Peu d’études biomécaniques sont disponibles sur le sujet et aucune ne traite particulièrement de la cinématique du PFR cervical. L’objectif de cette étude était de caractériser les paramètres angulaires et électromyographiques du PFR cervical dans deux différentes conditions expérimentales.

Patients et méthodes

Dix-neuf jeunes adultes (22,2 ± 2,4 ans) sans antécédents de cervicalgies ont pris part à cette étude. Les sujets ont réalisé une tâche de flexion de la colonne cervicale dans deux positions assises distinctes : tronc orienté verticalement et tronc incliné à 45° vers l’avant. Les variables dépendantes sont issues de la cinématique cervicale (angle d’apparition et de disparition du PFR) et de l’amplitude du signal EMG des muscles paraspinaux cervicaux et trapèzes supérieurs. Les variables ont été comparées à l’aide d’un test- t apparié afin de déterminer les différences entre les deux conditions expérimentales.

Résultats

Les sujets ont présenté en quasi-totalité (95 %) un PFR cervical au niveau des muscles paraspinaux. Le PFR a été observé unilatéralement dans 84,2 % (67,4 % bilatéralement) des essais en position assise verticale et dans 90,5 % (79,0 % bilatéralement) des essais en position assise inclinée. Le PFR apparaît en moyenne à 74,5 % en flexion et disparaît dans le mouvement d’extension au retour vers la position initiale à 92,5 % de l’amplitude maximale de la flexion cervicale. Aucune différence significative n’a été observée entre les deux conditions expérimentales pour les angles d’apparition et de disparition du PFR. Le ratio EMG extension–relaxation a été significativement plus élevé dans la position inclinée comparativement à la position verticale.

Conclusion

Nos résultats démontrent l’existence du PFR de la région cervicale et cette réponse est présente chez la quasi-totalité des sujets sains. Bien que les valeurs angulaires du PFR cervical ne soient pas influencées par la position du test, nos résultats suggèrent que la position avec le tronc incliné à 45° puisse faciliter l’évaluation de cette réponse neuromusculaire.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The physical examination and functional evaluation of the cervical spine are essential steps in the clinical management of neck pain. They enable the clinician to follow the evolution of a patient’s condition, and, in turn, evaluate the efficiency of its action and establish the prognostic. To achieve this, the clinician can look at two types of functional evaluation of the cervical spine: a subjective evaluation using questionnaires and an objective evaluation. Range of motion assessment, as well as orthopaedic and neurologic clinical examination carried out by the clinician are part of the objective functional evaluation . For such task, the clinician can use tools like the Cervical Range of Motion instrument (CROM) , for assessing cervical range of motion; force gauges and manual dynamometers for measuring muscle strength ; and electromyography (EMG) for estimating muscular efforts . Surface EMG can also be used to study certain neurophysiological phenomena, such as the flexion–relaxation phenomenon (FRP).

In 1955, Floyd and Silver described the FRP in the lumbar region as being a sudden reduction (“silence”) in the electromyographic signal of the lumbar paraspinal muscles as the trunk was undergoing complete flexion. This myoelectric “silence” is in fact electrical activity similar to that of tonic activity at rest. Its appearance can probably be explained by a transfer of the moment of extension from the active muscular structures to the passive structures of the spinal column . Approaching complete flexion, the contribution of the muscle contractile component contribution to spinal stability becomes less important. The lack of myoelectric “silence”, or persistence of EMG activity, during the complete flexion of the trunk has been shown to differentiate subjects with low-back pain from healthy subjects . In order to explain the lack of FRP in subjects with low-back pain, Solomonow et al. proposed a theoretical model where, following tissue damages to the lumbar spine, spasms and hyperexcitability of lumbar muscles develop in order to limit segmental motion and loading of viscoelastic structures.

Similarly to the lumbar region, the cervical FRP has been observed. It was first identified in 1966 by Pauly and Meyer et al. who identified this phenomenon in ten healthy subjects taking part in an experiment. More recently, Murphy et al. compared the EMG profile for FRP in healthy subjects and subjects with neck pain. Just like for the lumbar region, it appears that the absence of the myoelectric “silence” of the cervical paraspinal muscles could potentially be used to differentiate between subjects with neck pain and healthy subjects.

Certain methodological differences are however noted between the studies listed. Pauly and Carlsoo studied cervical FRP (cervical flexion) during a complete trunk flexion and did not systematically measure the cervical FRP in all healthy subjects. Meyer et al. modulated the velocity of the flexion task in a seated position in order to optimize the appearance of FRP for each subjects. Murphy et al. also isolated cervical flexion in a seated position and standardized the velocity of the movement, but did not specify the frequency at which cervical FRP was observed. Moreover, to our knowledge, no study has described the kinematics of cervical FRP in order to characterize onset and cessation angles.

The objective of this study is to characterize the kinematic and electromyographic parameters of the cervical FRP, in order to define onset and cessation angles and the extension–relaxation ratio (ERR) of electromyographic activity characterizing this “silence”. The second objective of the study is to compare the two evaluation positions for cervical FRP. One of the conditions selected accentuates the influence of the gravitational vector on the posterior structures of the cervical spine . We put forth the hypothesis that the position of the task will influence the kinematic and electromyographic parameters of cervical FRP.

1.2

Methodology

1.2.1

Subjects

Nineteen healthy adult subjects (12 women and seven men), aged 20 to 28, with no history of neck pain, participated in this study. All participants gave their informed, written consent according to the protocol approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the université du Québec à Trois-Rivières . Subjects with present or past neck pain, spinal trauma or cervical surgery were excluded from this experiment. Subject characteristics are presented in Table 1 .

| Attributes | Average (standard deviation) |

|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 22.2 (2.5) |

| Weight (kg) | 65.4 (12.7) |

| Height (m) | 1.71 (0.08) |

| Body mass index | 22.14 (2.5) |

1.2.2

Experimental protocol

Subjects were tested during one session of approximately 60 minutes in the laboratory. During the experimental session, subjects had to perform a standardized cervical flexion–extension movement in three phases:

- •

flexion phase: complete cervical flexion for four seconds;

- •

complete cervical flexion phase: static period in complete cervical flexion held for three seconds;

- •

and extension phase: extension to return to the initial position for four seconds.

Instructions were given to the subjects before each test and involved carrying out a full cervical-flexion movement while limiting protrusion of the head. A sound signal generated by a metronome-guided participant to ensure standardized test times and to reduce intra- and intersubject variability. Two practice trials were given to subjects for them to perform the flexion–extension task at the predefined pace. After a rest period, the subjects had to perform five tests in a seated position in two different positions:

- •

with the trunk vertical;

- •

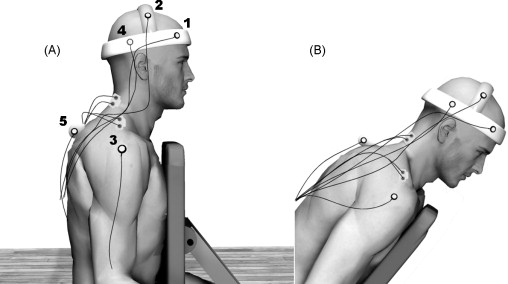

with the trunk inclined at 45° ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1

Subject and testing apparatus in the vertical position (A) and in the 45° incline position (B).

This second position was chosen to modify both the influence of the gravity vector and the stability requirements (shear force and flexion moment) in order to accentuate the myoelectrical activity of the cervical paraspinal muscles. To limit sequence effects, the test conditions order of presentation was randomly presented to each subject.

1.2.3

Instrumentation

Kinematic data were collected by a motion analysis system (Optotrak Certus, Northern Digital Inc., Waterloo, Canada). As shown in Fig. 1 , infrared diodes were positioned on the following anatomical sites: T2 spine process, right acromion, and three other diodes were set up in a triangular shape on the lateral right side of the helmet (180 g). Kinematic data were collected at a frequency of 100 Hz and low-pass filtered by a dual-pass, fourth-order Butterworth filter with a cut-off frequency of 5 Hz was applied. The angle of cervical flexion measured corresponds to the angle created by the right pulled between the markers 1 and 4 on the helmet, and the vertical is traced from the marker 5 on the T2 spinal process ( Fig. 1 ).

Bipolar disposable surface Ag-AgCl electrodes were applied bilaterally on the paraspinal muscles at the level of C4 and on the upper trapezius muscles. The electrodes were positioned in the direction of the muscle fibres, and skin impedance was reduced by removing the hair, using abrasion (3 M Red Dot Trace Prep) and rubbing the skin with an alcohol-soaked compress . Electromyographic data were collected using the Bortec Biomedical Acquisition System (Model AMT-8, common mode rejection ratio of 115 dB at 60 Hz, input impedance of 10 GΩ) and sampled at 900 Hz, using a 12-bit A/D converter (PCI 6024E, National Instruments, Austin, TX). EMG data were filtered at a bandwidth of 10 to 450 Hz and rectified. Data were processed using MatLab ® version 7.2 (Mathworks Inc, Natic, USA).

1.2.4

Data analysis

The ERR was calculated by dividing the root-mean-square (RMS) value during the extension phase by the RMS value of the EMG signal during the relaxation phase. The presence or absence of an FRP response was determined for each test by using a criterion of reducing the ERR ratio by more than 40%. The angles corresponding to the reduction of the EMG signal during the flexion phase (angle of FRP appearance) and to the increase of the EMG signal during the extension phase (angle of FRP disappearance) were identified through visual inspection of the rectified EMG signal for different muscles.

1.2.5

Statistics Analysis

Angles corresponding to the onset and cessation of myoelectric “silence” as well as the ERRs were compared during the different test conditions using a Student paired t -test. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05 for each analysis.

1.3

Results

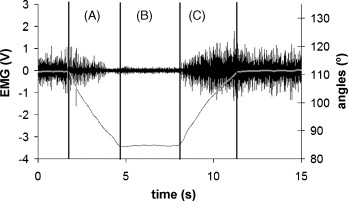

Fig. 2 illustrates a typical cervical FRP trial. An FRP of the cervical paraspinal muscles was shown in at least one test in 95% of subjects (18/19). The FRP of the cervical paraspinal muscles could be observed unilaterally in 84.2% (67.4% bilaterally) for tests in the vertical position, and in 90.5% (79.0% bilaterally) in tests in the inclined position. No FRP response was obtained at the upper trapezius muscles for any of the participants. Regarding the FRP onset and cessation angles, there was no significant difference seen between the two test positions ( p > 0.05). Table 2 presents the kinematic FRP parameters for the left and right paraspinal muscles during the two test conditions.

| Condition | Position A | Position B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | Left | Right | |

| Frequency of FRP (%) | 76.8 | 80.0 | 85.3 | 88.4 |

| Appearance angle (°) | 18.6 (5.1) | 19.3 (4.38) | 18.5 (6.0) | 18.3 (5.2) |

| Disappearance angle (°) | 23.2 (4.5) | 23.5 (4.5) | 22.91 (5.4) | 23.4 (4.9) |

| Appearance angle (%A max ) | 73.7 (8.8) | 76.3 (8.2) | 73.8 (13.8) | 72.6 (11.4) |

| Disappearance angle (%A max ) | 93.1 (3.2) | 93.0 (3.9) | 91.9 (9.7) | 92.9 (8.0) |

| ERR | 2.3 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.8) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.8) |

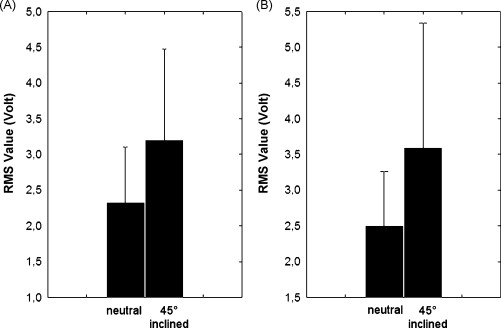

The ERR analysis, characterizing the change in the EMG signal amplitude during the FRP, indicates a significant increase ( p < 0.01) in this ratio during the inclined trunk position versus the vertical position. The ERRs were respectively 2.3 (0.8) and 2.5 (0.8) in the vertical position and 3.2 (1.3) and 3.6 (1.8) in the inclined trunk position for the left and right paraspinal muscle. Fig. 3 illustrates the differences seen in the ERRs for both test conditions. Lastly, a significant increase in the RMS value during the extension phase could be seen for the left and right paraspinal muscles. For the left paraspinal muscles, this value was 0.18 (0.09) volts and 0.30 (0.15) volts in the neutral position and in the inclined trunk position respectively ( p < 0.0001), whereas the RMS value for the right paraspinal muscles was 0.19 (0.10) volts in the neutral position, and 0.34 (0.18) volts in the inclined trunk position ( p < 0.0001).

1.4

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to examine the kinematics and electromyographic characteristics of the cervical FRP in two test positions. The results obtained indicate that almost all subjects tested presented a FRP in the cervical paraspinal muscles (18 subjects out of a total of 19). One major observation seen in our results is that the angles characterizing the FRP are not modified by the evaluation position. However, by accentuating the gravitational vector effect in the inclined position, increased amplitude is seen in the EMG ratio (ERR), which helps identify FRPs. The position effect is limited amplitude of the neuromuscular response and, therefore, has no effect on the temporal characteristics of the FRP.

The FRP was sometimes seen unilaterally during a few trials. Currently, there is no scientific data that can explain the presence of a unilateral FRP. However, it is possible that methodological factors (site of electrodes, execution of movement) could explain the unilateral presentation of the FRP. Moreover, given that the absence of FRP in subjects with low-back pain can also be seen in the asymptomatic phase , it is possible that a partial or incomplete clinical picture could explain the lack of FRP in the case of a sub-clinical condition affecting the cervical spine.

The majority of studies show that an increase in load or a change in posture can delay the appearance of the lumbar FRP . In this study, no effect was seen regarding the FRP appearance angles when changing the gravitational vector induced by a change in posture. The only effect observed was the increase in amplitude in the EMG signal. Since the angles characterizing the FRP remained the same, these results are a first step toward standardizing and developing a clinically useable measurement. To our knowledge, this study is the first to quantify the influence of increasing the gravitational constraints and the change in posture on the cervical FRP.

In this study, the velocity of movement during test conditions was controlled. Sarti et al. also showed that, increasing the velocity of movement in a flexion–relaxation task, delayed the onset of FRP during the lumbar flexion phase. Since the velocity of movement modulates the FRP parameters, it appeared important to control this parameter. Meyer et al. determined for each of their subjects an execution velocity that would obtain an eccentric extensor EMG burst during cervical flexion. To do this, subjects had to repeat the movement at different velocities until a cervical FRP was obtained. Knowing that the velocity of the movement and repetition of flexion can influence the viscoelastic properties of the paraspinal tissues and, thus, modify the lumbar flexion–relaxation response, we believe it is crucial to standardize the velocity of movement. However, the effects of velocity and repetition of movement on cervical FRP parameters remain unknown to date.

1.4.1

Clinical implications

Two studies have looked at the use of cervical FRP in the functional evaluation of patients with neck pain . As seen with the lumbar FRP, cervical FRP seems to be a reproducible physiological measurement that can be used to differentiate between healthy subjects and subjects with chronic neck pain . Moreover, trunk inclination seems to be an interesting alternative in evaluating cervical FRP, since this position involves an increase in the EMG signal amplitude without, however, influencing the kinematic parameters of the cervical flexion–relaxation response. Future studies related to the cervical FRP should be aimed at controlling factors known to influence the lumbar FRP. Effects of movement velocity, muscle fatigue effects and load effects should be assessed. Finally, treatment effects could be assessed using changes in flexion–relaxation responses following different types of treatment.

1.5

Conclusion

This study confirms the results of previous studies that have shown the existence of a FRP in the cervical spine. Additionally, it seems that the inclination of the trunk can facilitate the evaluation of this neuromuscular response. Cervical FRP reliability studies and studies designed to evaluate the FRP modulating factors should now be conducted in order to evaluate the relevance of using the FRP in the clinical context.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Renaud Jeffrey-Gauthier for his valuable help in carrying out this study, as well as the Quebec Chiropractic Foundation and the Institut franco-européen de chiropratique for their support.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’examen physique et l’évaluation fonctionnelle de la colonne vertébrale cervicale sont des étapes essentielles dans la prise en charge des cervicalgies. Elles permettent au clinicien de suivre l’évolution de la condition du patient et, ainsi, d’évaluer l’efficacité de son intervention et d’établir un pronostic. Pour y parvenir, le clinicien peut envisager deux types d’évaluation fonctionnelle de la colonne cervicale : une évaluation subjective par des questionnaires et une évaluation objective. L’examen manuelle de la mobilité ainsi que la réalisation d’un examen clinique orthopédique et neurologique effectué par le clinicien fait parti de l’évaluation objective fonctionnelle . Le clinicien peut s’aider, dans cette tâche, d’outils comme le Cervical Range of Motion instrument (CROM) permettant de mesurer les amplitudes de mouvement cervical, les jauges de force et dynamomètres manuels pour la mesure de la force musculaire ainsi que l’électromyographie (EMG) utilisée pour estimer les efforts musculaires . L’EMG de surface peut également être utilisée pour étudier certains phénomènes neurophysiologiques comme le phénomène de flexion–relaxation (PFR).

En 1955, Floyd et Silver décrivaient le PFR de la région lombaire comme étant une soudaine réduction (« silence ») du signal électromyographique des muscles paraspinaux lombaires à l’approche de la flexion complète du tronc. Ce « silence » myoélectrique est, en fait, une activité électrique similaire à celle de l’activité tonique de repos. Son apparition s’explique probablement par un transfert du moment d’extension des structures musculaires actives aux structures passives de la colonne vertébrale . D’un point de vue physiologique cela se traduirait, lors des derniers degrés de flexion, par une participation nulle de la composante active contractile musculaire au profit de la composante passive élastique musculaire et des structures ligamentaires. L’absence du « silence » myoélectrique, ou la persistance de l’activité EMG, lors de la flexion complète du tronc permet de discriminer les sujets atteints de lombalgies des sujets sains . Afin d’expliquer l’absence du PFR chez les sujets lombalgiques, Solomonow et al. ont proposé un modèle théorique selon lequel des dommages aux tissus lombaires entraînent une hyperexcitabilité et des spasmes des muscles lombaires afin de réduire le mouvement segmentaire et le stress mécanique que subissent les structures viscoélastiques.

Au même titre qu’au niveau de la région lombaire, le PFR de la colonne cervicale a été observé. Il fut d’abord identifié en 1966 par Pauly , et Meyer et al. observèrent le phénomène chez les dix sujets sains participant à leur expérimentation. Plus récemment, Murphy et al. ont comparé le profil EMG du PFR chez des sujets sains et des sujets atteints de cervicalgies. Tout comme pour la région lombaire, il semble que l’absence du « silence » myoélectrique des paraspinaux cervicaux soit un facteur discriminant les sujets atteints de cervicalgies des sujets sains.

Certaines différences méthodologiques sont cependant notées entre les études répertoriées. Pauly et Carlsoo ont étudié le PFR cervical durant une tâche de flexion complète au niveau du tronc (incluant une flexion cervicale) et n’ont pas mesuré systématiquement le PFR cervical chez tous les sujets sains. Meyer et al. ont modulé la vitesse de réalisation de la tâche, en position assise, pour optimiser l’apparition du PFR chez tous les sujets. Murphy et al. ont également isolé la flexion cervicale en posture assise et standardisé la vitesse de mouvement, mais n’ont pas spécifié la fréquence d’apparition du PFR cervical. De plus, à notre connaissance, aucune étude n’a décrit la cinématique du PFR cervical afin de caractériser ses angles d’apparition et de disparition.

L’objectif de cette étude est de caractériser les paramètres cinématiques et électromyographiques du PFR cervical, afin de définir les angles d’apparition/disparition et le ratio d’activités électromyographiques pouvant caractériser ce « silence ». Le second objectif de l’étude vise à comparer deux positions d’évaluation du PFR cervical. L’une des conditions choisies accentue l’influence du vecteur gravitationnel sur les structures postérieures de la colonne cervicale . Nous émettons l’hypothèse que la position de la tâche influencera les paramètres cinématiques et électromyographiques du PFR cervical.

2.2

Méthodologie

2.2.1

Sujets

Dix-neuf sujets sains adultes (12 femmes et sept hommes), âgés de 20 à 28 ans, sans antécédents de cervicalgie, ont pris part à cette étude. Tous les participants ont donné leur consentement éclairé écrit avant le début de l’expérimentation, le tout en accord avec le protocole approuvé par le comité d’éthique de la recherche avec les êtres humains de l’université du Québec à Trois-Rivières. Les sujets présentant des cervicalgies ou ayant déjà eu des douleurs cervicales, traumatismes spinaux ou encore une chirurgie au niveau cervical étaient exclus de la présente recherche. Les caractéristiques des participants sont présentées au Tableau 1 .