HIP REPLACEMENT

Approximately 330,000 total hip arthroplasties (THAs) were performed in the United States in 2010. The number of THA surgeries in this country has increased dramatically over the past four decades, and these procedures are expected to increase significantly by 2030.

The majority of hip replacements are performed in individuals between 60 and 80 years of age. Women account for 62% of such surgeries in the United States and typically undergo the procedure between ages 75 and 84 years (compared with ages 65 and 74 years for men). However, procedures are increasingly being performed in patients who are younger or older than this cohort, and advanced age is not a contraindication to THA. Differences in access to care and insurance coverage, as well as socioeconomic level, influence the demographic profile of patients who undergo the procedure. White Americans are more likely than African Americans to undergo THA (at 4.2 versus 1.7 per 1000 individuals), and individuals with higher incomes are 22% more likely to have the surgery than those with low incomes.

Indications for THA are listed in Table 33–1. The main goals of THA are to improve pain and restore function. Candidates for THA should have moderate to severe pain or disability and radiographic evidence of joint damage, which has not been relieved by conservative treatment. This includes a trial of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physical therapy, weight loss, activity modification, walking aids, and disease-specific treatments where appropriate. Absolute and relative contraindications to THA are listed in Table 33–2.

|

| Absolute Contraindications | Relative Contraindications |

|---|---|

|

|

The patient with chronic hip pain may complain of pain in the groin or buttocks that often radiates into the thigh. This pain is often described as a dull ache that is worse with activity and improves with rest. Examination may reveal decreased range of motion, groin or anterior thigh pain on straight-leg raise testing, limp, positive Trendelenburg test, and pain at extremes of range of motion.

Injury to the hip that produce Garden type III or IV fracture requires THA as definitive treatment. In these patients, the hip joint capsule along with the blood supply is disrupted and the patient is at high risk for necrosis of the femoral head. This finding is classically noted in the older individual with acute onset of hip pain after a fall. On examination, the limb appears to be externally rotated and shortened on the affected side.

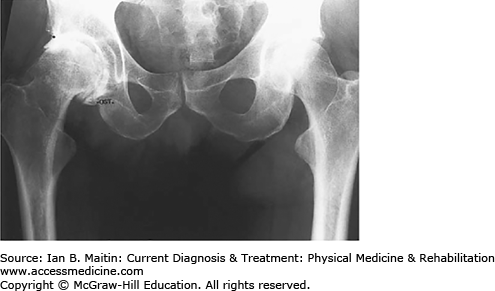

Radiographic findings of the osteoarthritic hip include asymmetric joint space narrowing, superior lateral joint space narrowing, subchondral bony sclerosis, osseous cysts, and absence of erosive changes (Figure 33–1). The rheumatoid hip will show symmetric joint space narrowing and, possibly, bone erosions.

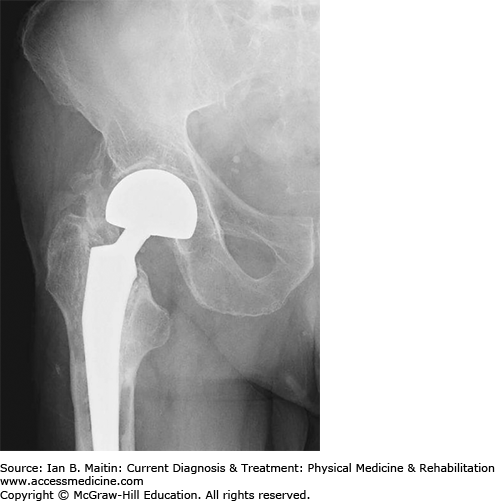

The femoral head and acetabulum are replaced during THA surgery, in contrast to hemiarthroplasty, in which only the femoral component is replaced. Hemiarthroplasty of the hip is indicated for displaced femoral neck fractures, osteonecrosis of the femoral head with sparing of the acetabulum, and certain cases of pathologic fractures and tumors. Hip arthroplasty varies in the type of prosthesis used (ie, unipolar versus bipolar), fixation of the prosthesis (cement versus cementless), formulation of the prosthesis (ceramic, plastic, or metal), and type of surgical approach (Figure 33–2).

In hemiarthroplasties, a unipolar or bipolar femoral prosthesis may be used. A unipolar prosthesis has only one large head that articulates with the acetabular cartilage. A bipolar prosthesis has two heads, allowing motion between one head and the acetabular cartilage and between the two heads. The theoretical advantage of this configuration is to reduce acetabular wear and increase range of motion. Bipolar implants are more expensive than unipolar; however, there appears to be no clinical difference in outcomes between patients receiving unipolar implants and those receiving bipolar implants in terms of acetabular wear and hip motion.

Attachment of the prosthetic components to bone can be achieved with cement or cementless fixation. When used, cement serves as the interface between the implant and bone; in the cementless approach, a porous implant surface is used to obtain a press fit to the bone.

Uncemented component fixation is nearly universally indicated. The advantages of a cementless fixation are long-lasting fixation and significant pain-free results. Cemented components have been shown to have a higher rate of loosening and have therefore fallen out of favor. However, cemented acetabular components may be indicated for patients with a life expectancy of 10 years or less and poor bone stock.

This is the most common surgical approach when performing THA. During this approach, the hip is internally rotated, adducted, and flexed. This approach is associated with the highest risk of hip instability postoperatively. This technique also places the sciatic nerve at risk for injury during dissection of the posterior hip capsule. However, the advantage is ease of anatomy, exposure, and avoidance of abductor musculature.

The anterior approach provides good exposure to the hip without requiring a trochanteric osteotomy. During this approach, the hip is extended, externally rotated, and abducted. This approach is associated with notable risks of injury to the femoral nerve, artery, or vein from prolonged anterior retraction. However, the advantages include excellent visualization of the femur and acetabulum as well as decreased postoperative risk of dislocation.

Complications from THA include, but are not limited to, infection, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, nerve palsies, dislocation, loosening of hardware, leg-length discrepancies, heterotopic ossification, trochanteric nonunion, and fracture. Patients are at greatest risk for these events from the acute postoperative period until 6 months after the operation.

Infection occurs in 0.4–1.5% of patients who undergo THAs. Unfortunately, this complication requires removal of the prosthesis, antibiotic therapy, and subsequent reimplantation of the components 1.5–6 months later. Consequently, sterile technique and prophylactic antibiotic therapy are essential to prevention.

THA surgery places patients at high risk for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and subsequent pulmonary embolism (PE). This is secondary to femoral vein damage, stasis, immobility, and hypercoagulability as a result of the operation. A previous history of DVT/PE, hormone replacement surgery, history of cancer, advanced age, female sex, obesity, and prolonged duration of surgery place patients at increased risk of these complications. PE is a potentially fatal complication, most often occurring in the first 2 weeks after the operation. Fortunately, the incidence of fatal PE is low, at 0.3%. An estimated 40–60% of THA patients will develop DVTs if they do not receive anticoagulation postoperatively. There is no consensus on appropriate anticoagulation status post-THA. However, low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, and fondaparinux are safe and effective options. The American College of Chest Physicians recommends anticoagulation for DVT prophylaxis for least 10 and preferably 35 days after THA.

The incidence of nerve injury in THA surgery ranges from 0 to 3%. Based on the surgical approach, certain nerves are more vulnerable to injury than others. The posterolateral approach is associated with risk of injury to the sciatic nerve, the most commonly injured nerve in THA surgery. Eighty percent of these injuries involve the peroneal distribution of the sciatic nerve, often leading to foot drop. The anterior approach risks damage to the femoral nerve, a complication in 1.7% of cases. In addition, the lateral femoral cutaneous, obturator, and superior gluteal nerves are susceptible to injury. Nerve injuries range from neurapraxia to neurotmesis. Nerve injury may be secondary to compression injury (hematoma), direct trauma, transection, or ischemia. Electromyography may aid in diagnosis of nerve injuries but typically shows no changes until 3 weeks postinjury. Treatment is typically conservative unless a large hematoma or nerve injury is suspected, in which case surgical exploration is indicated. Placing the hip and knee in flexion may decrease tension on the sciatic and femoral nerves. In addition, ankle–foot orthoses may help patients during the rehabilitation process. Prognosis is dependent on the extent of nerve injury, with isolated peroneal injury having a better outcome than complete sciatic palsy.

Hip dislocation rates vary by patient, surgeon, and surgical technique between 1% and 8%. Most hip dislocations occur within the first 4–6 weeks postoperatively and are associated with nonadherence to postoperative precautions and instructions. Higher rates of dislocation are associated with previous dislocation (the most important risk factor), female sex, revision surgery, use of the posterior surgical approach, poor muscular tone, femoral neck fractures, intellectual impairment, and advanced age.

Hip precautions must be upheld following THA surgery to avoid dislocation (Table 33–3). The risk of hip dislocation after THA decreases as time passes without dislocation. Once hip dislocation has been discovered, the source should be determined. Dislocation may be a result of patient nonadherence or improper component alignment. The first dislocation may be treated with closed reduction in the simple case of nonadherence or may require adjustment of the components. Abductor braces are helpful in the case of dislocation to assist in healing of lax tissue and help patients comply with their hip precautions. Revision surgery may be required in patients who sustain more than three dislocations.

| Anterior Approach Dislocation Precautions | Posterior Approach Dislocation Precautions | Global Dislocation Precautionsa |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

This complication is one of the major reasons for lawsuits after THA. Leg-length discrepancy may lead to a limp, cause low back pain, and require the use of assistive devices (canes). Consequently, patients require shoe lifts to compensate for leg-length differences. It is recommended that surgeons measure leg lengths preoperatively, account for preoperative leg-length differences (scoliosis, etc), express to patients the possibility of this outcome, and make surgical attempts if possible to avoid discrepancies that may be caused by laxity of soft tissues around the hip.

Heterotopic ossification (HO) is the formation of bone in inappropriate places (Figure 33–3). Severe cases of HO occur in 5–10% of THA surgeries. Risk factors include male sex (HO is twice as common in men as in women), prior occurrence of HO, age older than 65 years, ankylosing spondylitis, head injury, and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. The development of HO over weeks to months may be marked by hip pain or stiffness, decreased range of motion of the joint, fever, swelling, and tenderness to palpation. Diagnostic studies may reveal an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), elevated alkaline phosphatase level, and increased uptake on bone scan. Routine prophylaxis is not indicated for HO unless the patient has risk factors, as discussed above. Prophylactic therapies include NSAIDs (indomethacin is the most commonly used agent) or external beam radiation. These treatments are most beneficial when initiated 24–48 hours postoperatively.

For patients to make functional gains post-THA, postoperative rehabilitation is essential. During rehabilitation, patients should be monitored for adequate pain control. Inadequate pain control may result in poor or slow functional progress. Elderly patients must be monitored for sedation resulting from pain medications. Medications should be titrated so pain is adequately controlled without causing impaired mentation.

Bowel and bladder care are also integral to successful rehabilitation. Postoperative constipation is common secondary to pain medications and decreased mobility. To avoid postoperative ileus, early mobilization is key. Patients should also be placed on a bowel regimen as soon as possible postoperatively consisting of stool softeners, laxatives, and enemas if needed. If there are no issues with urinary retention, catheters should be discontinued on admission to the rehabilitation hospital. Management of urinary retention may necessitate urologic evaluation. Various strategies, which are usually surgeon dependent, are used to prevent thromboembolic complications; these include low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin. If warfarin is administered, the international normalized ratio (INR) should be maintained between 2.0 and 3.0. Weight-bearing restrictions also vary by surgeon. If a cemented prosthesis is used, the patient is usually able to bear weight as tolerated. However, when using a cementless prosthesis, partial or toe-touch weight bearing is usually recommended to allow for bony ingrowth.

To prevent hip dislocation, the patient must work with the therapy team to learn and abide by total hip precautions (as listed in Table 33–3). Abductor pillows should be provided to all THA patients to assist in compliance with posterior hip dislocation precautions. The rehabilitation team should also evaluate the patient to determine appropriate assistive devices, which will enable patients to comply with orthopedic weight-bearing recommendations and achieve functional gains. Inpatient rehabilitation should focus on transfers, ambulation, stair training, and activities of daily living (while maintaining total hip precautions). In addition, strengthening of the quadriceps and gluteal muscles is essential.

Overall the procedure is well tolerated, with a perioperative mortality rate of 0.7%. Sweden, which has the largest joint registry, demonstrated a 10-year survival rate of 91–94% in 93,000 implants, and similar results have been reported in published studies. Significant functional improvement on the Harris Hip score (from 51 preoperatively to 94 postoperatively) is seen in 86% of patients. Population-based studies revealed that 90% of THA patients were satisfied with the procedure and demonstrated functional improvement. In addition, 90% of prostheses were noted to be functioning without pain or complications 10–15 years postsurgery.

KNEE REPLACEMENT

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is one of the most common orthopedic procedures in the United States, with over 400,000 performed annually, and this number is expected to increase by as much as 673% by 2030. The average age of a patient undergoing TKA is 70 years. Two thirds of these patients are women, and one third are obese individuals (defined as those with a body mass index [BMI] > 30). Nearly 90% of patients undergoing TKA have a diagnosis of osteoarthritis. As with THA, there are sociodemographic differences in the patient population, with nonwhites receiving the operation half as often as their white counterparts.

Indications for TKA are listed in Table 33–4. The goals of TKA, similar to those of THA, are to improve pain and restore function. Candidates for TKA have knee pain that is unrelieved with conservative treatments such as medications, including NSAIDs and other pain relievers; physical therapy; weight loss; activity modification; bracing; and use of assistive devices. Absolute and relative contraindications to TKA are listed in Table 33–5.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree