Abstract

Objective and patient

To report an atypical case of exercise-induced bilateral brachialis and brachioradialis rhabdomyolysis in a 25-year-old woman.

Discussion and conclusion

Persistent focal muscle pain, atypical by its duration and intensity, even after moderate exercise, should prompt the search for rhabdomyolysis and discuss the possibility of acute compartment syndrome. MRI images can validate the muscle edema. Progressive and adapted training as well as respecting individual limits are necessary measures to prevent rhabdomyolysis.

Résumé

Objectif et patient

Décrire une observation rare de rhabdomyolyse des muscles brachial et des brachioradial déclenchée par un exercice de musculation chez une femme de 25 ans.

Discussion et conclusion

Un tableau douloureux focal inhabituel par son intensité et sa durée, même après un exercice modéré doit faire rechercher une lyse musculaire importante dont la complication locale la plus redoutable est le syndrome de loge aigu. L’IRM peut objectiver l’œdème musculaire. Un entraînement progressif et adapté, ainsi que le respect des limites individuelles sont les mesures préventives indispensables.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Independently of trauma factors, sport practice is often responsible for muscle pain, often deemed clinically benign after an intense, prolonged or unusual effort, but only if this pain remains moderate and limited over time. Muscle pain elicited by moderate exercise that is intense, long lasting with focal tenderness, as illustrated in our clinical case, should prompt the physician to screen for rhabdomyolysis that could potentially lead to severe complications.

1.2

Observation

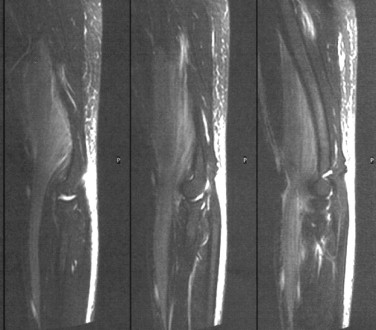

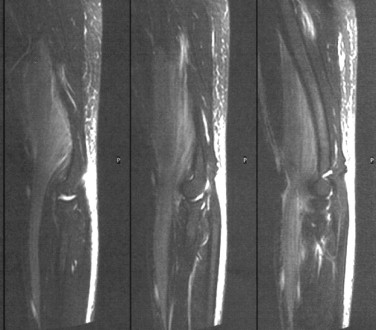

This 25-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with intense pain in her upper limbs and edema on her arms that had been progressing for the past 4 days. This patient was right-handed with no relevant medical history, she had been an emergency medical technician in the army for the past 6 years and was used to regular physical activity without any specific problems: her routine included a 45-minute running session in the morning and team sports in the afternoon for about 90 minutes. She was also used to adding one or two weightlifting sessions during the week with arm tractions and push-ups. She stopped all physical activities during a 3-week vacation period. When she returned to work she did her usual 45-minute running session and then added 30 minutes of push-ups and six series of five tractions, hands in pronation fixed on a bar located 190 cm from the floor, she needed another person to help her reach the bar. She experienced more difficulties than usual, knowing that she never did that many series in a row. In the evening she started feeling intense muscle pain and aches in the anterior part of her arms and forearms then the next day, she had some edema and intense muscle tension in the painful areas, more severe on the right side. She needed help to lift her bags. Elbow extension was painful. Upon admission to the emergency room on day 5, the pain in the brachialis muscles was more moderate but permanent with muscle tension and edema in the lower part of the arm compartment and the upper part of the external compartment of the forearm. No sensitive or motor deficits were observed. Deep tendon reflexes were present. Presence of peripheral pulses and skin coloration was normal. The examination unveiled some excess weight (82 kg for 172 cm). Blood tests validated the rhabdomyolysis with high creatine phosphokinase (CPK) at 38 913 U/L (N < 200), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 900 U/L (10 < N < 30), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 263 U/L (10 < N < 35), and myoglobinemia at 1236 μg/L (25 < N < 58). High lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were at 1236 U/L (210 < N < 420). Potassium levels were normal, so were kidney functions and complete blood count (CBC) test results. There was no inflammatory syndrome. T2-weighted MRI images done on the left side showed a marked homogeneous and spread out hyperintense lesion of the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles ( Fig. 1 ), without any abnormalities to the other muscles. T2-weighted images also showed hyperintense skin tissue lesions on the posterior part of the arm and forearm without any abnormalities to the arterial or venous flows. Pressure measurement done upon admission to the ER on the biceps brachii of the right arm (Stryker STIC technique) showed values at 10 mm Hg (N < 15 mmHg). In light of the biological and clinical results, simple monitoring was implemented with prescription of analgesics and proper hydration. The clinical evolution was positive, the pain quickly disappeared and biological values had greatly improved when she was discharged 7 days later (CPK at 338). One month later, MRI images were normal. The full check-up 4 months later included a clinical examination and electromyogram as well as a stress test under ischemic conditions in order to look for metabolic muscular dystrophy, all results were normal. The patient was able to get back to her exercise routine and chose not to reproduce the same type of intense effort; she has had no problems in the past 2 years.

1.3

Discussion

Our patient presented with rhabdomyolysis limited to the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles, cause by traction efforts. There is a good correlation between this type of exercise and the muscles affected, because during tractions on a fixed bar with hands in pronation the muscles most solicited, besides back muscles ( latissimus dorsi ) are the arm muscles especially of the anterior compartment i.e. biceps brachii , brachialis and brachioradialis. These last two muscles are the main elbow flexors when the wrist is in a fixed position and presented injuries compatible with the rhabdomyolysis clearly visible on the initial MRI, which proved its imaging relevance. The data were also well correlated to the clinical symptoms regarding the anterior compartments of the arms and external compartment of the forearms, sparing the other muscles, especially the triceps brachii and pectoralis major particularly solicited during push-ups. Other causes for this painful focal muscle edema (e.g. trauma, post-embolic or inflammatory disorders) were quickly discarded in favour of exercise being the triggering mechanism of this rhabdomyolysis. The brief, relatively intense and atypical nature of the effort, which included short series of tractions, needs to be underlined. In fact, no promoting factor, whether anatomical or MS-related was unveiled during the full check-up (MRI, EMG and stress test under ischemic conditions) or the 2-year follow-up. However, two factors could have had a negative impact and should be corrected before pursuing this type of exercise: getting back to an exercise routine too quickly without proper preparation and warm up, soliciting muscles that had been relatively undertrained by the vacation period; an unusual weight load for the patient above her physical capacities (unable to lift her own body weight with her arms) in a relatively overweight individual. The most feared complication related to rhabdomyolysis (even more than kidney failure or hyperkalemia) in case of focal muscle pain is acute compartment syndrome which is more commonly located in the legs, but rarer at thigh, forearm and mostly arm level. In fact, at this level, the reported cases for acute compartment syndrome are already quite scarce and exceptionally triggered by exercise . The impact of this mechanism to the clinical picture merits to be discussed in this observation since post-exercise rhabdomyolysis usually concerns several muscles that empty their contents into the blood stream and not one or two isolated muscles . Typically the clinical picture of acute compartment syndrome is quite clear : intense pain starting during exercise but not preventing it, lingering on and worsening over time even when having stopped all efforts, requiring emergency aponeurotomy to prevent irreversible ischemic nerve and muscle damage. Moreover, there exists another recurrent chronic compartment syndrome type , with painful claudication spontaneously resolving when the effort stops, yet in this case the triggering threshold gets lower over time and if the pathology is overlooked it could turn into acute compartment syndrome. Giving up the triggering physical activity is the alternative to a delayed aponeurotomy to avoid recurrence . For acute compartment syndrome intramuscular pressure regularly goes beyond 50 mm Hg whereas for chronic compartment syndrome values at rest are 15 mm Hg at rest and 20 mm Hg 5 minutes after stopping the effort . The normal values obtained in this clinical case could be explained by the delayed measure taken 5 days after the pathology had set in and the fact that it concerned the biceps brachii (which was normal at the MRI), and not the brachialis or brachioradialis.

We usually consider that the effort triggering acute compartment syndrome should be intense, unusual or repeated in a patient whose training is inadequate or inappropriate, as seen in our clinical case, whereas it should be regular and intense for chronic compartment syndrome. The precarious balance between the compartment itself and its content could explain the absence of symptoms at rest in the case of chronic compartment syndrome, but this equilibrium would be broken during exercise. The muscle’s physiological increase up to 20 or 30% of it volume during exercise, caused by functional hyperemia and edema in an inextensible compartment seems to trigger some hyper pressure leading to muscle and nerve ischemia followed by necrosis in the most severe clinical pictures.

The rare occurrence of compartment syndrome in the arms could be explained by anatomical factors with tendons and ligaments that are looser, smaller and more flexible with a less resistant and more extensible aponeurosis, and some type of communication with the shoulder’s compartment .

1.4

Conclusion

Pre-requirements to any type of physical exercise are progressive and adapted warm up and training sessions while knowing how to respect one’s own physiological limits in order to avoid severe rhabdomyolysis with general and/or local damages, such as acute compartment syndrome feared when faced with painful symptoms that are focal, intense and long lasting.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La pratique sportive est souvent responsable, indépendamment des facteurs traumatiques, de myalgies qui sont jugées bénignes après un effort soutenu, prolongé ou inhabituel, à condition de rester modérées et limitées dans le temps. Même produites par un exercice modéré, leur caractère inhabituellement intense, durable et focal, comme l’illustre l’observation présentée, doit faire redouter une rhabdomyolyse qui expose à des complications potentiellement graves.

2.2

Observation

Une jeune femme de 25 ans s’est présentée aux urgences pour des douleurs intenses des membres supérieurs associées à un œdème des bras évoluant depuis quatre jours. Droitière, sans antécédent, elle était brancardière secouriste dans l’armée depuis six ans, pratiquant à ce titre une activité physique régulière sans gêne particulière : il s’agissait d’une séance de 45 minutes de course à pied le matin et souvent d’un sport collectif l’après-midi durant une heure et 30 minutes. Elle ajoutait une ou deux séances de musculations par semaine avec des tractions des bras et des pompes. Elle avait interrompu toute activité sportive durant trois semaines de congé. À son retour de vacances, elle a effectué le premier jour après un footing de 45 minutes, une séance de 30 minutes durant laquelle elle a fait des pompes et surtout six séries de cinq tractions, mains fixées en pronation sur une barre située à 190 cm du sol avec l’aide d’une autre personne pour se hisser. Elle avait alors rencontré beaucoup plus de difficultés qu’à son habitude, sachant qu’elle n’avait jusque là jamais fait autant de séries à la suite. Le soir même, elle a ressenti de vives myalgies et des courbatures au niveau de la partie antérieure des bras et des avant-bras puis le lendemain matin, elle a constaté un œdème et une forte tension musculaire au niveau des zones douloureuses, plus marquée à droite. On a dû lui porter ses sacs. L’extension du coude était douloureuse. À sa prise en charge aux urgences le cinquième jour, les douleurs brachiales et antébrachiales étaient plus modérées mais permanentes, avec une tension musculaire et un œdème au niveau de la moitié inférieure de la loge antérieure du bras et de la partie supérieure de la loge externe de l’avant-bras. Il n’existait ni déficit sensitif ni moteur. Les réflexes ostéo-tendineux étaient présents. Les pouls périphériques étaient perçus et la coloration cutanée normale. Un surpoids relatif était noté (82 kg pour 172 cm). Sur le plan biologique sanguin, on retrouvait une rhabdomyolyse, avec des CPK à 38 913 U/L (N < 200), des ASAT à 900 U/L (10 < N < 30), des ALAT à 263 U/L (10 < N < 35), et une myoglobinémie à 1236 μg/L (25 < N < 58). Les LDH était élevé à 1236 U/L (210 < N < 420). La kaliémie était normale comme la fonction rénale et la formule sanguine. Il n’existait pas de syndrome inflammatoire. L’IRM réalisée à gauche a mis en évidence un muscle brachial hyperintense en T2 de façon homogène et étendue, comme le brachioradial ( Fig. 1 ), sans anomalie des autres muscles. Le tissu cutané paraissait lui aussi hyperintense en T2 de façon prédominante à la face postérieure du bras et de l’avant-bras, sans anomalie du flux artériel ou veineux. La mesure de pression dans le biceps brachial droit (technique Stryker STIC) a montré le jour de l’admission une valeur égale à 10 mm Hg (N < 15 mmHg). Devant la bonne tolérance clinique et biologique, une surveillance simple fut décidée avec prescription d’antalgiques et d’une hydratation, ce qui permit une évolution favorable avec une disparition rapide des douleurs et une nette amélioration des paramètres biologiques à sa sortie sept jours plus tard (CPK à 338). L’IRM un mois plus tard s’était normalisée. Le bilan à quatre mois comportant examen clinique, électromyogramme et un test d’effort sous ischémie à la recherche d’une myopathie métabolique s’est avéré normal. La patiente a pu reprendre ses activités physiques, en s’interdisant par choix personnel de reproduire le même type d’effort, sans éprouver de gêne avec un recul de près de deux ans.