Intramedullary Fixation of Clavicle Fractures

Stephen B. Gunther

Carl Basamania

DEFINITION

The clavicle is one of the most commonly fractured bones.

The site on the clavicle most often fractured is the middle third.10

The midclavicular region is the thinnest and narrowest portion of the bone.

It is the only area not supported by ligament or muscle attachments.

It represents a transitional region of both cross-sectional anatomy and curvature.

It is the transition point between the lateral part, with a flatter cross-section, and the more tubular medial portion of the bone.

Because of the clavicle’s S shape, an axial load creates a very high tensile force along the anterior midcortex. (Axial load makes a virtual right angle at midclavicle.)

ANATOMY

The clavicle is the only long bone to ossify by a combination of intramembranous and endochondral ossification.7

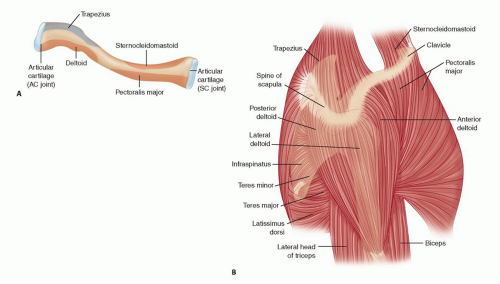

Its configuration is S-shaped, a double curve; the medial curve is apex anterior and the lateral curve is apex posterior (FIG 1A).

The larger medial curvature widens the space for the neurovascular structures, providing bony protection.

The clavicle is made up of very dense trabecular bone, lacking a well-defined medullary canal.

The cross-sectional anatomy gradually changes from flat laterally, to tubular in the midportion, to expanded prismatic medially.

The clavicle is subcutaneous throughout, covered by the thin platysma muscle.

The supraclavicular nerves that provide sensation to the overlying skin of the clavicle are found deep to the platysma muscle.

Very strong capsular and extracapsular ligaments attach the medial end to the sternum and first rib and the lateral end to the acromion and coracoid.

Proximal muscle attachments include the sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis major, and subclavius. Distal muscle attachments include the deltoid and trapezius (FIG 1B).

The clavicle functions by providing a fixed-length strut through which the muscles attached to the shoulder girdle can generate and transmit large forces to the upper extremity.

PATHOGENESIS

The mechanism of clavicle fractures in the vast majority is a direct injury to the shoulder.11 Stanley and associates11 studied 106 injured patients; 87% had fallen onto the shoulder, 7% were injured by a direct blow on the point of the shoulder, and only 6% reported falling onto an outstretched hand.

Stanley suggests that in the patients who described hitting the ground with an outstretched hand, the shoulder became the next contact point with the ground, causing the fracture. Stanley stated that a compressive force equivalent to body weight would exceed the critical buckling load to cause the clavicle fracture.

NATURAL HISTORY

In the 1960s, both Neer8 and Rowe10 published large series of midclavicle fractures, showing very low nonunion rate (0.1% and 0.8%) with closed treatment and a higher nonunion rate (4.6% and 3.7%) with operative treatment.

More recent studies have shown that nonunion is more common than previously recognized and that a significant percentage of patients with nonunion are symptomatic.

Malunion with shortening greater than 15 to 20 mm has also been shown to be associated with significant shoulder dysfunction.

McKee and colleagues6 identified 15 patients with malunion of the midclavicle after closed treatment. All patients had shortening of more than 15 mm, all were symptomatic and unsatisfied, and all underwent corrective osteotomy. Postoperatively, all 15 patients improved in terms of function and satisfaction.

Hill and associates5 reviewed 52 completely displaced midshaft clavicle fractures and found that shortening of more than 20 mm had a significant association with nonunion and unsatisfactory results.

Eskola and coworkers4 reported on 89 malunions of the midclavicle, showing that shortening of more than 15 mm was associated with shoulder discomfort and dysfunction.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The diagnosis is usually straightforward and is based on obtaining the mechanism of injury from a good history.

On visual inspection, the examiner will frequently see notable swelling or ecchymosis at the fracture site and possibly deformity of the clavicle, with drooping of the shoulder downward and forward if the fracture is significantly displaced. The skin is inspected for tenting at the fracture site and characteristic bruising and abrasions that might suggest a direct blow or seatbelt shoulder strap injury (FIG 2A,B).

Palpation over the fracture site will reveal tenderness, and gentle manipulation of the upper extremity or clavicle itself may reveal crepitus and motion at the fracture site.

The amount of shortening can be identified by clinically measuring the distance of a straight line (in centimeters) from both acromioclavicular (AC) joints to the sternal notch and noting the difference (FIG 2C) or by measuring directly on digital x-rays.

It is important to perform a complete musculoskeletal and neurovascular examination of the upper extremity and auscultation of the chest to identify the rare associated injuries; these are more frequently seen when there is a high-energy mechanism of injuries.

Rib and scapula fracture

Brachial plexus injury (usually traction to upper cervical root)

Vascular injury (subclavian artery or vein injury associated with scapulothoracic dissociation)

Pneumothorax and hemothorax

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

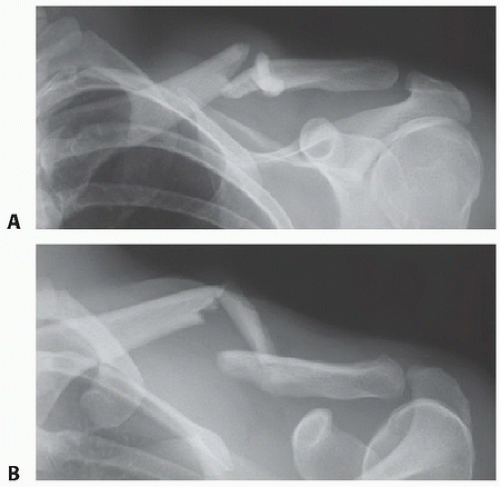

Two orthogonal radiographic projections are necessary to determine the fracture pattern and displacement, ideally 45-degree cephalic tilt and 45-degree caudal tilt views.

Usually, a standard anteroposterior (AP) view and a 45-degree cephalic tilt (FIG 3) view are adequate.

In practice, a 20- to 60-degree cephalic tilt view will minimize interference of thoracic structures.

The film should be large enough to include the AC and sternoclavicular joints, the scapula, and the upper lung fields to evaluate for associated injuries.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Sprain of AC joint

Sprain of sternoclavicular joint

Rib fracture

Muscle injury

Kehr sign: referred pain to the left shoulder from irritation of the diaphragm, signaled by the phrenic nerve. Irritation may be caused by diaphragmatic or peridiaphragmatic lesions, renal calculi, splenic injury, or ectopic pregnancy.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

If the clavicle fracture alignment is acceptable, generally a simple configuration with less than 15 mm of shortening, then any of a number of methods of supporting the upper extremity may be adequate: figure-8 bandage, sling, and Velpeau dressing.

Nordqvist and colleagues9 reported on 35 clavicle fracture malunions with shortening of less than 15 mm. They were all treated nonoperatively in a sling. All 35 had normal mobility, strength, and function compared to the normal shoulder.

A prospective, randomized study2 comparing sling versus figure-8 bandage showed that a greater percentage of patients were dissatisfied with the figure-8 bandage, and there was no difference in overall healing and alignment. The study concluded that the figure-8 bandage does little to obtain reduction.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications for operative treatment of acute midshaft clavicle fractures are as follows:

Open fractures

Fractures with neurovascular injury

Fractures with severe associated chest injury or multiple trauma: patients who require their upper extremity for transfer and ambulation

“Floating shoulder”

Impending skin necrosis

Fracture displacement: more than 15 to 20 mm of shortening (especially if there is associated shoulder girdle protraction and shortening)

In a multicenter, randomized, prospective clinical trial of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures, Altamimi and McKee1 showed that operative fixation compared to nonoperative treatment improved functional outcome and had a lower rate of both malunion and nonunion.

Potential advantages of intramedullary (IM) versus plate fixation of the clavicle are as follows:

Less soft tissue stripping and therefore potentially better healing

Smaller incision

Better cosmesis

Easier hardware removal

Less weakness of bone after hardware removal

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree