Intra-Articular Therapy

David H. Neustadt

Ray Altman

Intra-Articular Steroids in Osteoarthritis

In 1951, hydrocortisone was introduced and popularized for local intra-articular administration. Observations and a vast experience accumulated during the intervening years have confirmed the value of this compound and of other corticosteroid suspensions for combating pain and inflammation when they are given at the local tissue level.1,2,3

Although the value of intra-articular steroids in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthropathies is undoubted, their use in the therapy for osteoarthritis (OA) has been controversial.4 Early experimental studies suggested the possibility of a neuropathic Charcot-like arthropathy after multiple corticosteroid injections,5,6,7 and studies performed on small animals (i.e., mice, rats, and rabbits) indicated evidence of altered cartilage protein synthesis and damage to the cartilage.3,8,9,10,11,12 These deleterious effects curbed the enthusiasm for intra-articular corticosteroid therapy in OA. However, other investigators reported that clinical observations after repeated administration of intra-articular steroids to knees demonstrated no significant evidence of destruction or accelerated deterioration.13,14 A detailed study of the effects of steroid injections on monkey joints disclosed no appreciable joint damage, suggesting that primate joints probably respond in a different way from those of mice and rabbits.15 Most authorities now consider intra-articular corticosteroid therapy in OA of considerable value when administered appropriately and judiciously. Intra-articular steroid therapy is always considered as an adjunctive form of therapy added to a conventional management program.

Rationale

The major objective of intrasynovial therapy in OA is to enter the joint space, aspirate any fluid, and instill the corticosteroid suspension that suppresses inflammation and provides the most effective relief for the longest period of time.

The metabolic pathway and fate of corticosteroids within the joint have not been completely elucidated.3 Some evidence of the injected steroid can be detected in the synovial fluid cells for 48 hours after injection. Prednisolone trimethylacetate has been identified in synovial fluid 14 days after its injection. The rate of absorption and duration of action are related to the solubility of the compound instilled.16 Triamcinolone hexacetonide is the most insoluble preparation currently available.1

An antilymphocytic action is considered a possible mechanism of steroid benefit on rheumatoid synovial lining. Corticosteroids inhibit prostaglandin synthesis and decrease collagenase and other enzyme activity. The major basis of benefit in OA remains somewhat unclear. Saxne and coworkers17 measured the release of proteoglycans into synovial fluid to monitor the effects of therapy on cartilage metabolism. Their data strongly suggest that intra-articular corticosteroid injections reduce the production of mediators such as interleukin (IL)-1, TNF-alpha, and other so-called protease enzymes that may induce cartilage degradation.

Systemic “spillover” with absorption may occur, varying with the size of the dose and the solubility of the preparation injected. One study showed that 40 mg of methylprednisolone acetate was sufficient to induce a transient adrenal suppression, as reflected in depressed cortisol levels for up to 7 days.16 A postinjection rest regimen (Table 16-1) or partial limitation of motion of the injected joint probably delays “escape” of the intra-articular steroid and minimizes systemic overflow effects.18

Indications

It is important to emphasize that intra-articular steroid therapy must be considered an adjunct to basic measures. Except in treating a strict regional problem such as

traumatic synovitis or olecranon bursitis, it should be thought of as a component modality included in a comprehensive management program.

traumatic synovitis or olecranon bursitis, it should be thought of as a component modality included in a comprehensive management program.

TABLE 16-1 POSTINJECTION REST REGIMEN | ||

|---|---|---|

|

The indications for the use of intra-articular steroids are summarized in Table 16-2. In addition to the goal of introducing a drug into the joint cavity, arthrocentesis permits the aspiration of synovial fluid, which is useful as a diagnostic aid. Examination of the synovial fluid permits an estimation of the presence and degree of inflammation. An experienced observer can usually distinguish rheumatoid from traumatic or osteoarthritic fluid by its gross appearance and viscosity. Only a few drops of fluid may suffice to establish the diagnosis of an accompanying crystal synovitis (gout or pseudogout).

When usual conventional therapy has failed to control the symptoms adequately or prevent disability, local steroid therapy deserves consideration. A tense or painful effusion is the strongest indication for prompt arthrocentesis, followed by a corticosteroid injection, pending synovial fluid findings to exclude infection.

Relief of pain with preservation or restoration of joint motion is the major objective of therapy. When one or more joints are resistant to systemic therapy, consideration should be given to intrasynovial injections. Local joint injections are often helpful in preventing adhesions and correcting flexion deformities of the knee. In large, tense, or boggy effusions, the capsule and ligaments may become stretched, and this can be combated effectively with intra-articular therapy. Finally, in longstanding or recurrent effusions of the knee, a so-called “medical synovectomy” can be performed by instilling a relatively large dose (30 to 50 mg) of an insoluble preparation such as triamcinolone hexacetonide, followed by a strict postinjection rest regimen (Table 16-1).

TABLE 16-2 INDICATIONS FOR INTRASYNOVIAL CORTICOSTEROIDS | |

|---|---|

|

Clinical Efficacy

Numerous authors reported favorably on the use ofintra-articular steroids in the treatment of OA.3,19,20,21,22,23 Balch and associates13 reported on repeated intrasynovial injections given over a period varying from 4 to 15 years. The minimum number of injections given was 15 during a period of 4 years, with the interval between injections being not less than 4 weeks. Their results strongly supported the conclusion that this was a “very useful” form of treatment.

Although certain controlled trials24,25 failed to demonstrate significant efficacy of steroid injections, these studies did not take into consideration such important factors as adequate dosage, the presence or absence of fluid, removal of excess fluid (dilution factor), and the injection technique. Most important, there was no attempt to regulate the postinjection physical activity of the patient.

Dieppe and colleagues26 reported a beneficial response with significantly greater reduction of pain and tenderness compared with placebo in a controlled trial in which 20 mg of triamcinolone hexacetonide were injected into 48 osteoarthritic knees. These results were obtained even though injections were made into the infrapatellar pouch and only 5 mL of fluid were aspirated from each knee at the time of the procedure. In another report27 of 42 patients with OA in whom triamcinolone hexacetonide, betamethasone acetate, and betamethasone disodium were compared, the results confirmed that intra-articular steroid treatment of OA was highly effective. In another other study27,28 including a similar comparative assessment in a group consisting of 19 patients with OA of the knee, favorable results were obtained.28 The duration of effect varied with different preparations and dosage.

These carefully performed randomized double-blind and single-blind studies support the results of Hollander’s1 30 years of experience with a large number of injections. He reported that in a 10-year follow-up of the first 100 patients who had been given repeated intra-articular steroids in osteoarthritic knees, 59 patients no longer needed injections, 24 continued to require occasional injections, and only 11 did not obtain a worthwhile response.23

My own experience is similar to that of Hollander and the other authors cited previously. Striking relief of pain, frequently coupled with increased motion, occurred in the majority of injected joints. However, the success of short-term

beneficial response must be balanced against the all-important duration of effect and any potential iatrogenic deleterious response.

beneficial response must be balanced against the all-important duration of effect and any potential iatrogenic deleterious response.

Contraindications and Complications

The role of intra-articular corticosteroids in OA remains somewhat controversial despite extensive use and reported beneficial response because of some reports of the development of steroid induced (Charcot-like) arthropathy after multiple injections.5,7

Contraindications are relative and are listed (Table 16-3). Local infection or recent serious injury overlying the structure to be injected or the presence of a generalized infection with possible bacteremia is an obvious contraindication to the local instillation of a corticosteroid or any local injection. In patients with systemic infections, intra-articular therapy might be performed under the “cover” of appropriate antibiotic therapy, if the indication is considered urgent. The risk of provoking serious bleeding in patients receiving anticoagulants must be determined after a review of the patient’s general status, including determination of the prothrombin time. Joints of the lower extremities that demonstrate considerable underlying damage (e.g., an unstable knee) should not be injected with corticosteroids unless there is a relatively large inflammatory effusion and the patient will cooperate by adhering to a non-weight-bearing rest schedule for several weeks after the procedure.

Complications of intra-articular therapy are listed in Table 16-4. Despite some systemic “spillover,” physical evidence of hypercortisonism or other undesirable steroid effects rarely occur from intermittent intra-articular therapy. If “moon” face appears, injections may have been administered too frequently.29 Although the possibility of introducing an accidental infection is the most serious potential complication, review of our extensive experience and that of others discloses that infections occurring as an aftermath of joint injections are extremely rare.1,3,30

Local adverse reactions are minor and reversible. The so-called postinjection flare is a rare complication that begins shortly after the injection and usually subsides within a few hours, rarely continuing up to 48 to 72 hours. Some investigators consider these reactions to be a true crystal induced synovitis caused by corticosteroid ester crystals.2,31 The application of ice to the site of injection and oral analgesics usually control after-pain until the reaction abates. In a few instances, the postinjection synovitis has been sufficiently severe to require aspiration of the joint to obtain relief.

TABLE 16-3 RELATIVE CONTRAINDICATIONS TO INTRA-ARTICULAR THERAPY | |

|---|---|

|

TABLE 16-4 COMPLICATIONS OF INTRA-ARTICULAR THERAPY | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Another infrequent complication is localized subcutaneous or cutaneous atrophy.2,3 This cosmetic change can be recognized as a thin or depressed area at the site of the injection, sometimes associated with depigmentation. As a rule, the skin appearance will be restored to normal when the crystals of the corticosteroid have been completely absorbed. Rarely, capsular (periarticular) calcification at the site of the injection has been noted in roentgenograms taken after treatment. The calcifications usually disappear spontaneously and are not of clinical significance.18 Careful technique to prevent the steroid suspension from leaking along the needle track to the skin surface will avoid or minimize this problem. A small amount of 1% lidocaine (or equivalent) or normal saline solution can be utilized to flush the needle used to administer the crystalline suspension before removing the needle.

An occasional patient may complain of transient warmth and flushing of the skin. There may be central nervous system and cardiovascular reactions to local anesthetics if used in combination with the steroid for injection. It has been suggested that the abolition of pain after the introduction of steroids permits the patient to “overwork” the involved joint, causing additional cartilage and bone deterioration and finally giving rise to a Charcot-like or steroid arthropathy.32 In addition, experimental evidence in rabbit joints indicates that frequently repeated injections of corticosteroids may interfere with normal cartilage protein synthesis.3,12 As stated earlier, studies on primate joints failed to confirm evidence of significant cartilage damage caused by repeated administration of intra-articular steroids, suggesting that the steroid effect on primate joints, including human joints, is probably temporary.15 Indeed, evidence of a “protective effect” of corticosteroids against cartilage damage and osteophyte formation has been shown with triamcinolone hexacetonide in a guinea pig knee model of experimental arthritis.33

TABLE 16-5 INJECTABLE CORTICOSTEROIDS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Available Compounds and Choice of Drugs

Hydrocortisone and a variety of available repository preparations are listed in Table 16-5. All corticosteroids, with the exception of cortisone and prednisone, can produce a significant and prompt anti-inflammatory effect in an inflamed joint. The most soluble corticosteroid suspension is absorbed rapidly and has a short duration of effect. Tertiary butyl acetate (TBA, tebutate) ester prolongs the duration of action as a result of decreased solubility, which probably causes its dissociation by enzymes to proceed at a lower rate. Although an occasional patient may obtain greater benefit from one steroid derivative than from another, no single steroid agent has demonstrated a convincing margin of superiority, with the exception of triamcinolone hexacetonide.6,23,34 Prednisolone tebutate has the virtues of price advantage and longtime usage; unfortunately, it is currently relatively unavailable because of “manufacturing” problems. Depomethylprednisolone and triamcinolone hexacetonide may be substituted. Triamcinolone hexacetonide is the least water-soluble preparation currently available. It is 2.5 times less soluble in water than prednisolone tebutate and usually provides the longest duration of effectiveness. There is minimal systemic “spillover” with this agent.

Dosage and Administration

The dose of any microcrystalline suspension employed for intrasynovial injection must be arbitrarily selected. Factors that influence the dosage and the anticipated results are listed in Table 16-6.

For estimating dosage, a useful guide is as follows:

For small joints of the hand and foot, 2.5 to 10 mg of methylprednisolone acetate suspension or an equivalent glucocorticoid

For medium-sized joints such as the wrist and elbow, 10 to 25 mg

For the knee, ankle, and shoulder, 20 to 40 mg

For the hip, 25 to 40 mg

TABLE 16-6 FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE RESPONSE TO INTRA-ARTICULAR INJECTIONS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

It is occasionally necessary to give larger amounts to obtain optimal results. For intrabursal therapy, such as for the hip (trochanteric) or the knee (anserine) bursa, 15 to 40 mg is usually an adequate dose.

The longer the intervals between injections, the better. I usually recommend a 4-week minimum between intra-articular procedures, and in weight-bearing joints, I prefer an interval of at least 6 to 12 weeks between injections. Injections should not be repeated on a “regular” routine basis, and rarely should more than two to three injections into a specific weight-bearing joint be repeated per year. Injections into soft tissue sites of para-articular inflammation may be given on a more frequent basis. After knee injection, I advise the patient to adhere to the following rest regimen (Table 16-1). The patient should remain in bed for 3 days, with the exception of getting up for bathroom privileges and meals; crutches are then prescribed, to be used with “three-point” gait to protect the injected knee during distance walking for 2 to 4 weeks. A cane may be substituted at times when crutches are considered inappropriate or uncomfortable. This postinjection rest regimen facilitates a sustained improvement and avoids the hazard of “overworking” or abusing the injected joint. An additional benefit is that the inactivity reduces any systemic effect by delaying absorption of the steroid from the synovial joint cavity. This program is optimal for achieving maximal therapeutic benefit and reducing possible deleterious effects of joint overuse after injection. However, as with all therapeutic programs, rheumatologists may vary the regimen based on the individualized needs of the given patient. Experimental evidence indicates that during exercise of the inflamed human knee, there is a large increase in intra-articular (hydrostatic) pressure, which causes intra-articular hypoxia.35 On cessation of exercise, there is oxidative damage to lipids and immunoglobulin G (IgG) within the joint. The lipid peroxidation products in synovial fluid are not found in resting knees. Reperfusion of the synovial membrane occurs when exercise is stopped.

During the past several years, I have hospitalized five patients with OA of the knees who had intractable, recurrent synovitis resistant to frequent arthrocenteses and repeated intra-articular injections. After the administration of a steroid (usually triamcinolone hexacetonide) and the completion of the strict rest period, these patients obtained complete resolution of effusions for up to a year or longer.

Preparation of Injection Site

Preparation of the site for injection of a steroid requires rigid adherence to aseptic technique. Landmarks are outlined with a skin pencil or ball point pen. The point of entry is then cleansed with an antibacterial cleanser (antimicrobial soap or the equivalent) or a povidone-iodine solution, and alcohol is sponged on the area. Sterile drapes and gloves are not ordinarily considered necessary. Sterile 4-inch x 4-inch gauze pads are useful for drying the area.

Injection Techniques

General Considerations

Arthrocentesis is easily and relatively painlessly performed in a joint that is distended with fluid or when boggy synovial proliferation is present. For most joints, the usual point of entry is on the extensor surface, avoiding the large nerves and major vessels that are usually present on the flexor surface. Optimal joint positioning should be accomplished to stretch the capsule and separate the joint “ends” to produce maximal enlargement and distraction of the joint or synovial cavity to be penetrated.

A local anesthetic may be desirable, especially when a relatively “dry” joint is being entered or when only a small amount of fluid is present. A small skin wheal made by infiltration with lidocaine or the equivalent or spraying (frosting) the skin with a vapocoolant such as chloroethane (ethyl chloride) usually provides adequate anesthesia.

Aspiration of as much synovial fluid as possible prior to instillation of the corticosteroid suspension reduces the possible dilution factor. After the therapeutic agent is injected in large joints, it may be advisable to reaspirate and reinject several times within the barrel of the syringe (barbotage) to obtain good “mixing” and dispersion of the therapeutic compound throughout the joint and synovial cavity. I often instill a small amount of air just prior to removing the needle to ensure adequate diffusion. Finally, gentle manipulation, carrying the joint through its full excursions of motion, facilitates maximal dispersion of the injected medication.

Specific Joints and Adjacent Sites

The joints most frequently considered for corticosteroid injection in OA include the knee, the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints, the first carpometacarpal joint, and the first metatarsophalangeal joint. The hip and temporomandibular joints are less commonly injected. Shoulder joints are rarely involved in primary OA but, like the elbow, may develop OA on a secondary, underlying basis.

Technique for Knee Injection

The knee joint contains the largest synovial space in the body and is the most commonly aspirated and injected joint. Demonstrable, visible, or palpable effusions often develop, making it the easiest joint to enter and inject with medication. When a large amount of fluid is present, entry is as simple as puncturing a balloon.

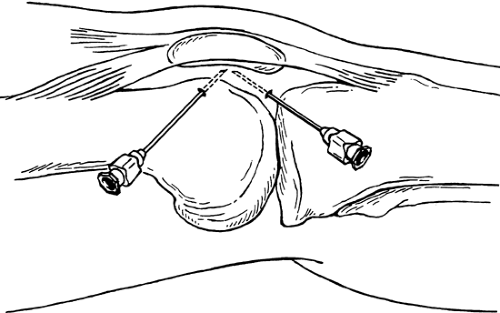

Aspiration of the knee is usually performed with the patient lying on a table with the knee supported and extended as much as possible. The usual site of entry is medial at about the midpoint of the patella or just below the point where a horizontal line tangential to the superior pole of the patella crosses a line paralleling the medial border. The needle (1.5- to 2-inch, 20-gauge) is directed downward or upward, sliding into the joint space beneath the undersurface of the patella (Fig. 16-1). Aspiration of the knee can be facilitated by applying firm pressure with the palms cephalad to the patella over the site of the suprapatellar bursa. If cartilage is touched, the needle is withdrawn slightly and the fluid is aspirated. A similar approach can be used on the lateral side especially if the maximal fluid bulge is present laterally. The lateral approach is especially convenient if there is a large effusion in the suprapatellar bursa. The point of penetration is lateral and superior to the patella. An approach that is used less frequently is the infrapatellar anterior route, which is useful when the knee cannot be fully extended and there is only minimal fluid present. With the knee flexed to approximately 90°, the needle is directed either medially or laterally to the inferior patellar tendon and cephalad to the infrapatellar fat pad. It is difficult to obtain fluid with this approach, and there is a slight possibility of injury to the joint surface.

Knee Region

Although radiographic evidence of degenerative changes involving the knee may be present, the “knee” pain and associated disabling symptoms sometimes result from extra-articular causes. Some of these painful conditions in the knee region, often associated with OA, may respond to local injection therapy.

These disorders include bursitides of the knee with involvement of the prepatellar, suprapatellar, and anserine bursae. Other disorders adjacent to the knee that may be responsive to injection therapy include semimembranosus tenosynovitis, Pelegrini-Stieda syndrome, and painful points around the edge of the patella associated with patellofemoral OA. The differential diagnosis between OA of the knee and these disorders is based on a thorough history and the physical findings.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree