Intoeing

David A. Spiegel

B. David Horn

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

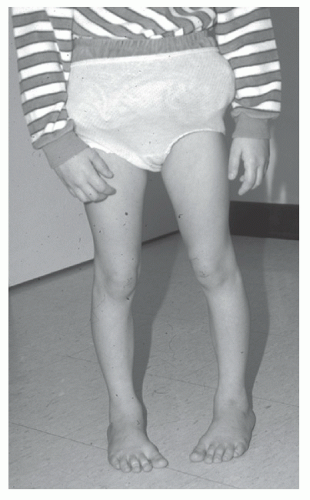

Intoeing results from inward rotation at the foot, lower leg, or hip and is a frequent cause for parental concern in infants, toddlers, and children.1-4 Inward rotation at more than one location may be observed. In toddlers and younger children, parents observe that the child frequently trips and falls. They may complain that the child is sustaining multiple bruises as a result of these falls. There is often a history of mild improvement, and a history of progressive worsening in rotational alignment suggests the presence of an underlying diagnosis. While intrauterine position influences alignment of the lower extremities during early life, genetic factors determine the rotational alignment at skeletal maturity in the absence of coexisting pathology. Families should be questioned regarding the presence of intoeing in other family members and any conditions or diseases which might be associated with abnormalities in rotational alignment (neuromuscular, metabolic, skeletal dysplasias). For example, abnormal findings on the birth and/or developmental history may suggest a diagnosis of cerebral palsy. The most common diagnosis in infants is metatarsus adductus, which is a deformation due to intrauterine positioning. While medial tibial torsion is seen most frequently in toddlers and younger children, internal femoral torsion becomes clinically apparent at 3 to 5 years of age, and girls are affected more frequently than boys. Most torsional deformities improve or resolve with time, and a careful history and physical exam should identify those few patients who require further evaluation and/or treatment.

CLINICAL POINTS

The deformity is a frequent concern of parents.

Intoeing is may be observed in infants, toddlers, and children.

The inward rotation may occur at the foot, lower leg, or hip (or more than one level).

Bowing of the legs may be observed along with intoeing in infants and toddlers.

Physical examination focuses on the rotational profile, which determines the location of the inward rotation.

Most measurements fall within the range of normal variation.

Intoeing commonly improves with time and treatment is rarely required.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

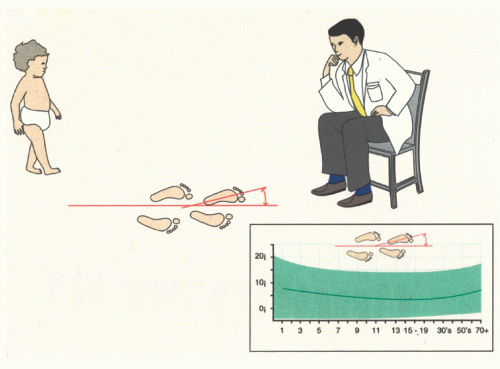

The general physical examination should include the measurement of height, as patients below the 25th percentile may potentially have a skeletal dysplasia or metabolic disease depending upon the family history and associated clinical findings. A rotational profile should be documented for all patients to determine both the location (foot, lower leg, or hip) and magnitude of inward rotation.1,2,3,4 This profile includes (1) the foot progression angle (Fig. 54-1), (2) the alignment of the foot, (3) the thigh-foot axis (Fig. 54-2)

or transmalleolar axis, and (4) the degree of femoral rotation (Fig. 54-3).1,2,3,4 Findings on the rotational profile may be compared with normative data to determine where each child falls within the range of values for the population. From a more scientific perspective, we should define “torsion” as rotational values which are more than 2 standard deviations from the mean. As such, most cases of so-called femoral and tibial torsion are within the normal range of variation. Internal rotation may be identified at more than one location, for example, metatarsus adductus is commonly associated with internal tibial torsion, and a patient can have both internal tibial torsion and internal femoral torsion. While difficult to quantify, patients may also have a muscular or dynamic component to their intoeing. Parents can be counseled and reassured after the evaluation, and the few children who deviate significantly from the physiologic range of values can be identified. Less than 1% of patients will ultimately require active treatment. A notable exception external tibial torsion, who have the appearance of “knockknees” or valgus limb alignment, and who may have patellofemoral symptoms.

or transmalleolar axis, and (4) the degree of femoral rotation (Fig. 54-3).1,2,3,4 Findings on the rotational profile may be compared with normative data to determine where each child falls within the range of values for the population. From a more scientific perspective, we should define “torsion” as rotational values which are more than 2 standard deviations from the mean. As such, most cases of so-called femoral and tibial torsion are within the normal range of variation. Internal rotation may be identified at more than one location, for example, metatarsus adductus is commonly associated with internal tibial torsion, and a patient can have both internal tibial torsion and internal femoral torsion. While difficult to quantify, patients may also have a muscular or dynamic component to their intoeing. Parents can be counseled and reassured after the evaluation, and the few children who deviate significantly from the physiologic range of values can be identified. Less than 1% of patients will ultimately require active treatment. A notable exception external tibial torsion, who have the appearance of “knockknees” or valgus limb alignment, and who may have patellofemoral symptoms.

The foot progression angle represents the inward or outward rotation of the foot (degrees) relative to the direction of ambulation or line of progression (Fig. 54-1). This quantifies the degree of intoeing but does not identify the location of the inward rotation.

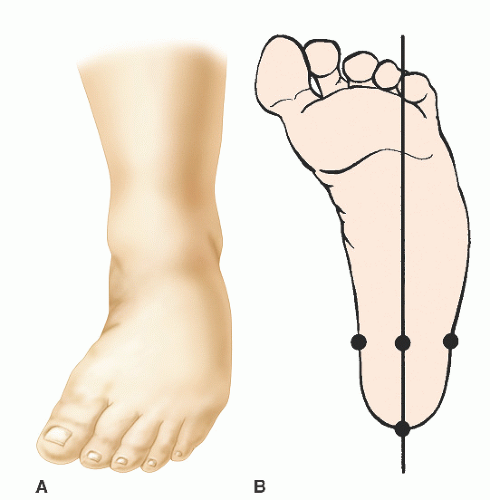

Inspection of foot alignment will reveal whether the lateral border is straight, and a line bisecting the heel should normally go through the second web space. Inward deviation of the forefoot relative to the hindfoot is termed metatarsus adductus (Fig. 54-2A and B).5,6 The lateral border of the foot is convex, and sometimes there is plantarflexion of the medial column of the foot (high arch), in which case it is referred to as metatarsus varus. It is important to determine the flexibility of the deformity. If the forefoot can be abducted beyond neutral (a line bisecting the heel passes medial to the first toe), the metatarsus adductus is flexible. If the forefoot can be brought just to a neutral alignment (lateral board is straight), the foot is “partly flexible.” If alignment cannot be brought to the neutral position, the deformity is “inflexible.” The most rigid deformities may be due to congenital bony abnormalities such as a trapezoidal medial cuneiform. Metatarsus adductus must also be differentiated from other foot deformities in which there is adduction of the forefoot, and the distinction depends on the evaluation of hindfoot alignment. While the hindfoot (visualize the calcaneus from behind) is neutrally aligned in

metatarsus adductus, it is inward (varus) in a clubfoot and outward (valgus) in a skewfoot. Since metatarsus adductus is usually an intrauterine deformation, it may be associated with other deformations such as congenital muscular torticollis. Any infant with metatarsus adductus (or any positional foot deformity such as a positional clubfoot or a calcaneovalgus foot [everted and dorsiflexed, lying on the anterolateral lower leg in severe cases]) should have a careful examination of the hips. Metatarsus adductus is often associated with a dynamic hallux abductus or varus, in which the great toe points further inward when the patient is standing or walking, but not when they are nonweightbearing. This dynamic deformity is felt to result from imbalance between the abductor and the adductors of the great toe. Passive range of motion of the great toe will be normal.

metatarsus adductus, it is inward (varus) in a clubfoot and outward (valgus) in a skewfoot. Since metatarsus adductus is usually an intrauterine deformation, it may be associated with other deformations such as congenital muscular torticollis. Any infant with metatarsus adductus (or any positional foot deformity such as a positional clubfoot or a calcaneovalgus foot [everted and dorsiflexed, lying on the anterolateral lower leg in severe cases]) should have a careful examination of the hips. Metatarsus adductus is often associated with a dynamic hallux abductus or varus, in which the great toe points further inward when the patient is standing or walking, but not when they are nonweightbearing. This dynamic deformity is felt to result from imbalance between the abductor and the adductors of the great toe. Passive range of motion of the great toe will be normal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree