Abstract

Objectives

Treatment complexity of cerebral palsy (CP) patients imposes outcome evaluation studies, which may include objective technical analysis and more subjective functional evaluation. The Edinburgh Gait Score (EGS) was proposed as an additive or alternative when complex instrumented three-dimensional gait analysis is not available. Our purposes were to apply a translated EGS to standard video recordings of independent walking spastic diplegic CP patients, to evaluate its intraobserver and interobserver reliability with respect to gait analysis familiar and not familiar observers.

Methods

Ten standard video recordings acquired during routine clinical gait analysis were examined by eight observers gait analysis interpretation experienced or not, out of various specialities, two times with a two weeks interval. Kappa statistics and intraclass correlation coefficient were calculated.

Results

Better reliability was observed for foot and knee scores than in proximal segments with significant differences between stance and swing phase. Significantly better results in gait analysis trained observers underlines the importance to either be used to clinical gait analysis interpretation, or to benefit of video analysis training before observational scoring.

Conclusion

Visual evaluation may be used for outcome studies to explore clinical changes in CP patients over time and may be associated to other validated evaluation tools.

Résumé

Objectifs

Le traitement des patients atteints de paralysie cérébrale (PC) impose des études d’évaluation incluant des analyses techniques objectives et des évaluations fonctionnelles subjectives. L’Edinburgh Gait Score (EGS) a été proposé comme alternative à l’analyse tridimensionnelle de la marche (AQM). Nos objectifs étaient d’appliquer une version française d’EGS à partir d’enregistrements vidéo de patients marchant, diplégiques spastiques, puis d’évaluer sa fiabilité intra- et interobservateurs.

Méthode

Dix enregistrements vidéo acquis au cours d’une AQM ont été interprétés à deux reprises, par huit observateurs expérimentés ou non dans l’AQM, provenant de diverses spécialités. Les statistiques Kappa et le coefficient de corrélation intraclasse ont été calculés.

Résultats

Une meilleure fiabilité a été observée pour le pied et le genou comparé aux segments proximaux, avec des différences significatives entre le stance et le swing. Les résultats ont été significativement meilleurs chez les observateurs expérimentés en AQM, ce qui souligne l’importance d’être soit habitué à interpréter l’AQM, soit de bénéficier d’une formation de l’analyse d’observation de la marche avant son interprétation.

Conclusion

L’évaluation visuelle peut être utilisée pour étudier les résultats des changements cliniques chez les patients PC et peut être associée à d’autres outils d’évaluation validés.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Instrumented three-dimensional gait analysis that provides quantitative measures is now the Gold Standard for gait assessment in the context of decision-making and outcome evaluation in walking cerebral palsy children .

Three-dimensional gait analysis may be considered at the moment as the evaluation Gold Standard and has been shown to be a clinically effective evaluation tool .

Summary measures may be more representative methods to determine the amount by which function and gait deviate from normative values. Thus patient’s global gait pathology may be described using instrumented gait analysis using the Gillette Gait Index (GGI, formerly Normalcy Index) based on a selection of gait variables considered most pertinent to CP patients .

But a complete movement analysis laboratory is not universally available in all institutions. It is expensive and requires time consuming work of data treatment and high-level of interpretation skills . Additionally existing well-equipped gait laboratories are confronted to an important patient flux.

Day-by-day clinical work may be complemented introducing different evaluation tools like functional scores, quality of life and daily activity scores.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) furnishes us the framework to construct global outcome evaluation programs. To use this conceptual framework, definitions of the concepts have to be very precise and placed within a clinical context. The ICF introduces the concepts of “structure and function”, “activity and participation” in the context of personal and environmental factors. Gait analysis has to be placed in the function level.

Clinicians in charge of cerebral palsy children routinely observe gait to determine gait disorders and to evaluate treatment.

Therefore, observational gait analysis (OGA), a part of three-dimensional gait analysis, may be an interesting available help, specifically using standardised gait scales.

First different “naked eye” observation of gait tools were used to assess the gait of various patient groups and to evaluate outcome .

To overcome the problems with naked eye evaluation of gait, specifically video-based observational gait assessment was developed with forms and scales to standardise evaluation .

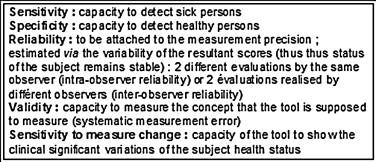

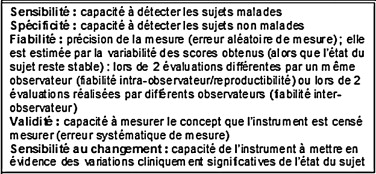

Nevertheless according to the relative subjective nature of OGA, an evaluation tool used for sharing of clinical information between clinicians and for multi-center research should meet best criteria of validity, reliability, sensitivity and specificity ( Fig. 1 ). This tool has to be considered in the context of patient population and the nature of gait pathologies studied. Therefore, in the clinical context of cerebral palsy (CP) treatment, the tool to choose should be developed for CP children. To use OGA as an objective outcome evaluation tool different observational scales were introduced to enhance quality of analysis and to produce quantitative comparable data.

Validation work is still necessary but at time of the study the previous criteria were met best for the Edinburgh Gait Score (EGS) .

The EGS was developed as a visual scoring system easy to use, reliable, correlating well with instrumented gait analysis results, that may be used to evaluate archived cine films.

Association and comparison of observational and instrumented 3-D gait analysis data is interesting and a recent study validated the EGS as standard evaluation tool with significant correlations with the GGI .

The authors of the score demonstrated its good intraobserver and interobserver reliability, good correlation with measurements from instrumented gait analysis. Further the score was able to detect postoperative changes after multilevel surgery .

Reliability comparison between the EGS and the Physician Rating Scale studied by Maathuis et al. showed excellent intraobserver but poor interobserver reliability for children with cerebral palsy (CP) . The authors recommend that longitudinal assessment of a patient should be done by one observer only.

According to our aim to introduce the EGS as regular outcome evaluation tool in our country, we have to explore the factors influencing intraobserver and interobserver reliability to complete user’s instructions.

Therefore the purpose of our study was to evaluate intraobserver and interobserver reliability of the Edinburgh Gait Score with respect to gait analysis familiar and not familiar observers.

1.2

Material and methods

1.2.1

Observational gait analysis

A series of 10 archived video recordings acquired during standardized instrumented gait analysis were randomly selected and examined.

Gait analysis data were acquired using a 6-camera optoelectronic system with passive markers (ELITE, Bts, Milan, Italy) working at a sampling rate of 50 Hz at the authors’ center of motion analysis. Subjects equipped with markers according to Davis’ description were asked to walk barefoot, at self selected speed, on the walkway containing three Kistler force platforms.

All the 10 patients, aged 9 to 16 years, had a diagnosis of spastic diplegic cerebral palsy. The videos for observational gait analysis were acquired in sagittal and coronal view simultaneously.

Eight observers examined 10 videos recordings two times, at a minimum of two weeks between the assessments. The eight observers were selected from various specialties: three paediatric orthopaedic surgeons, one resident in orthopaedic surgery, one neurosurgeon, one physiatrist and two physiotherapists. Observers assessed videos randomly and were blinded at the second lecture to their first results.

Clinical experience with cerebral palsy and gait analysis experience of each observer was noted.

Translated guidelines were provided to observers who rated each patient video using the tabulated EGS scoring system ( Table 1 ) for each lower limb at six anatomical levels: trunc, pelvis, hip, knee, ankle and foot in sagittal, transverse and frontal plane .

| Stance phase | Swing phase | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion | Normal | Extension | Flexion | Normal | Extension | ||||||

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Pied | Pied | ||||||||||

| 1. Initial contact | Contact avec talon | Contact pied à plat | Contact des orteils | 6. Clearance in swing | Pas haut | Complet | Réduit | Inexistant | |||

| 2. Décollement du talon | Pas de contact de l’avant-pied | Retardé | Normal | Tôt | Pas de contact avec talon | 7. Angle maximal de dorsilexion | Dorsiflexion excessive (> 30°) | Dorsiflexion augmentée (16–30°) | Dorsiflexion normale (15°C DF – 5° FP) | Flexion plantaire modérée (5–20°) | Flexion plantaire marquée (> 20°) |

| 3. Angle maximum de dorsiflexion | Dorsiflexion excessive (> 40°) | Dorsiflexion augmentée (26–40°) | Normal (5–25°) | Dorsiflexion réduite (4° DF – 10° FP) | Flexion plantaire marquée | ||||||

| 4. Arrière pied : varus/valgus | Valgus sévère | Valgus modéré | Neutre/léger valgus | Varus modéré | Varus sévère | ||||||

| 5. Rotation du pied | RE marquée (> 40°) | RE modérée (21–40°) | RE légère (0–20°) | RI modérée (1–25°) | RI marquée (> 25°) | ||||||

| Genou | Genou | ||||||||||

| 8. Angle de progression du genou | Externe : une partie de rotule visible | Externe : toute la rotule visible | Neutre : rotule centrée | Interne : toute la rotule visible | Interne : une partie de rotule visible | 10. Terminal swing | Flexion sévère (< 30°) | Flexion modérée (16–30°) | Normale (5–15̊) | Extension excessive (4° flexion – 10° extension) | Hyperextension (> 10°) |

| 9. Extension maximale en stance | Flexion sévère (> 25°) | Flexion modérée (16–25°) | Normal (0–15° flexion) | Hyperextension modérée (1–10°) | Hyperextension sévère (> 10°) | 11. Flexion maximale en swing | Augmentation marquée (> 85° de flexion) | Augmentation modérée (71–85°) | Normale (50–70°) | Réduction modérée (35–49°) | Réduction sévère (< 35°) |

| Hanche | Hanche | ||||||||||

| 12. Extension maximale en stance | Flexion sévère (> 15°) | Flexion modérée (1–15°) | Normal (0–20° extension) | Hyperextension modérée (21–35°) | Hyperextension sévère (> 35°) | 13. Flexion maximale en swing | Augmentation marquée (> 60°) | Augmentation modérée (46–60°) | Normale (25–45°) | Flexion réduite (10–24°) | Réduction sévère (< 10°) |

| Pelvis | |||||||||||

| 14. Obliquité en mid-stance | Vers le bas, marquée (> 10°) | Vers le bas, modérée (1–10°) | Obliquité normale (0–5° vers le haut) | Vers le haut, modérée (6–15°) | Vers le haut, marquée (>15°) | ||||||

| 15. Rotation en mid-stance | Rétropulsion marquée (> 15°) | Rétropulsion modérée (6–15°) | Normal (rétropulsion 5° – antépulsion 10°) | Antépulsion modérée (11–20°) | Antépulsion sévère (> 20°) | ||||||

| Tronc | |||||||||||

| 16. Position sagitale maximale | Vers l’avant, marquée | Vers l’avant, modérée | Normal (vertical) | Vers l’arrière, modérée | Non applicable | ||||||

| 17. Déplacement latéral maximal | Marqué | Modéré | Normal | Réduit | Non applicable | ||||||

1.2.2

Statistics

For statistical analysis, the total EGS score and the 17 items individually were considered, as well as we grouped the items per anatomical level and in between stance and swing phase items.

For each observer, the Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was computed between the two times of evaluation to assess intraobserver reliability in each quantitative scale (five dimension scores and total EGS score). Values were interpreted as follows: below 0.20 regarded as poor, 0.21–0.40 as fair, 0.41–0.60 as moderate, 0.61–0.80 as good and >0.80 as very good agreement .

For each evaluation time, interobserver agreement of the total and grouped scores was assessed using the ICC. Interobserver agreement on each of the 17 gait items (ordinal data) was studied using the weighted Kappa coefficient.

Weighted Kappa coefficient for interobserver reliability and the intraclass correlation coefficient for intrarater reliability were calculated according to the traditional methods. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability for the 10 video recordings and 160 assessments were extensively explored.

Non-parametric partial correlations (Spearman’s correlation coefficients) were studied to investigate the relationship of the total EGS score between the two times of evaluation, while controlling either the effect of clinical or gait analysis experience (years) (first order of partial correlation) or both (second order of partial correlation) .

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All statistical analysis were performed using SPSS 11.0 and SAS.

1.3

Results

In the context of clinical experience in cerebral palsy and gait analysis experience, we observed moderate to very good agreement of the eight observers between their two successive evaluations. Differences were shown looking at the subscores. Specifically pelvis, hip and trunk score results were lower ( Table 2 ).

| Observer (type) | Experience | Edinburgh Visual Gait Score (ICC) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical (years) | Gait Analysis (years) | Total | Trunc | Pelvis | Hip | Knee | Foot | |

| 1. OS | 18 | 0 | 0.71 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 0.91 |

| 2. OS + GLM | 15 | 12 | 0.88 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.62 | 0.85 | 0.89 |

| 3. OS + GLM | 6 | 6 | 0.89 | 0.60 | 0.17 | 0.76 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| 4. P + GLM | 15 | 3 | 0.69 | 0.12 | −0.31 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.90 |

| 5. PT | 10 | 0 | 0.59 | 0.16 | −0.34 | 0.11 | 0.67 | 0.27 |

| 6. NS | 4 | 0 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 0.94 |

| 7. Resident OS | 2 | 0 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.97 | 0.99 |

| 8. PT + GLM | 2 | 0 | 0.96 | 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.95 |

An increased number of items with better interobserver agreement indicates a learning effect between the two rating times, even the observers were blinded to their first ratings ( Table 3 ).

| Reliability category | Total | Trunk | Pelvis | Hip | Knee | Foot | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t1 | t2 | t1 | t2 | t1 | t2 | t1 | t2 | t1 | t2 | t1 | t2 | |

| Number of items with increased category at t2 | 16/28 (57.1%) | 19/28 (67.9%) | 16/28 (57.7%) | 13/28 (46.4%) | 7/28 (25%) | 14/28 (50%) | ||||||

Therefore, analysing the total and the five subscores in 51% of the interobserver comparisons, the reliability improved between the two rating sessions ( Table 4 ).

| Score | Segment | Gait cycle | Rated gait event | Number of increased interobserver reliability between two ratings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Foot | Stance | Initial contact | 17/28 (60.7%) |

| 2 | Foot | Stance | Heel lift | 12/28 (42.9%) |

| 3 | Foot | Stance | Max ankle dorsiflexion | 9/28 (32.1%) |

| 4 | Foot | Stance | Hindfoot: varus/valgus | 14/28 (50%) |

| 5 | Foot | Stance | Foot rotation | 19/21 (67.9%) |

| 6 | Foot | Stance | Clearance | 8/28 (28.6%) |

| 7 | Foot | Swing | Peak dorsiflexion angle | 11/28 (39.3%) |

| 8 | Knee | Stance | Knee progression angle | 8/28 (28.6%) |

| 9 | Knee | Stance | Peak extension | 6/28 (21.4%) |

| 10 | Knee | Swing | Terminal swing | 12/28 (42.9%) |

| 11 | Knee | Swing | Peak flexion | 11/28 (39.3%) |

| 12 | Hip | Stance | Peak extension | 14/28 (50%) |

| 13 | Hip | Swing | Peak flexion | 13/28 (46.4%) |

| 14 | Pelvis | Stance | Obliquity at mid stance | 11/28 (39.3%) |

| 15 | Pelvis | Stance | Rotation at mid stance | 17/28 (60.7%) |

| 16 | Trunk | Stance | Peak sagittal position | 18/28 (64.3%) |

| 17 | Trunk | Stance | Max lateral shift | 19/28 (67.9%) |

We observed further significant better reliability for stance than swing phase items.

Clinical experience in cerebral palsy treatment influenced correlations. Gait analysis experience do not increase by itself the values compared to the simple correlations. But we observed further influence on correlation of increasing clinical and gait analysis experience ( Table 5 ).

| Patient | Simple | CE | GAE | CE + GAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.98 |

| 2 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.75 |

| 3 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.85 |

| 4 | 0.59 | 0.81 | 0.58 | 0.79 |

| 5 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.71 |

| 6 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.51 |

| 7 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.93 |

| 8 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| 9 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.30 |

| 10 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.80 |

1.4

Discussion

EGS reliability level is influenced by observer’s clinical experience in CP patients and its gait analysis experience.

Toro et al. noted that often experts in gait assessment were used in reliability studies and their ability to correctly and repeatable identify events in complex gait pathologies is unlikely to reflect the ability of a broader and less specialised user population. Our results showed that clinical experience influences the reliability results. Experience with gait analysis is added to this effect. Experience and training based on a solid knowledge of gait may enhance the repeatability in observational gait analysis . To ensure comparable reliability between centers, it is important to have observers with close level of experience and to know this experience for interpretation of the results.

Interestingly looking at each observer of our study separately even in the gait analysis not familiar group, degree of reliability correlates well with years and the extend of daily clinical work with cerebral palsy children.

Our results may explain that observers have been described as a significant factor for the source of variation . But authors used only three observers and more important did not describe in detail observers’ experience.

Using more than one statistical test may provide a better picture of the score reliability .

A variety of statistical methods exist for agreement analysis between respondents . The extent of agreement between raters is a characteristic of a sample as a whole, summarized by a single number such as a correlation coefficient.

Although overall reliability of the scale was satisfying comparable to the Edinburgh authors’ results , we have observed differences in the subscales and items, specifically for the proximal segments and swing phase ratings. Differentiation of the items and subscales may help to continue the development of the scale.

One limitation of our study was that we did not use the recommendations about rotation blocks to improve accuracy of scoring . But one of the EGS authors’ purposes was to develop a scoring system that could be used to evaluate archived films. We used our archived standard gait analysis videos with good global patient view, but without close up views on feet what may decrease quality of analysis. Application on historic videos without patient preparation seems to be more difficult. Nevertheless the lower reliability items in our study were the same than in the Edinburgh study.

Applications in daily clinical practice do not allow complex patient preparation with specific devices. But standardisation of numeric video acquisition conditions as for instrumented 3D-gait analysis may be very helpful to have comparable data.

Looking at our data, we propose now to our correspondents a minimal protocol to prepare observational gait analysis. We ask to acquire a complete gait cycle of the patient in frontal and right and left lateral view, first the whole patient, then close up views on the feet in the same conditions. Camera has to be in fixed position, the patient exposed to good lightening conditions, barefoot, with a sports or bathing dress and the ASIS, patella and the Achilles tendon ink marked for better visualisation.

Although not all clinicians may be or have to be equipped with a complete gait laboratory, standardized observational gait analysis may be considered as a minimal working tool. Learning visualisation of the different gait phases or observational gait analysis training based on a specific rating tool could also be useful. This would help to increase the use of gait assessment in a wider population of clinicians managing gait disorders, without the necessity to learn specific instrumented gait analysis data.

Instrumented gait analysis is important for a careful assessment of pathology in CP children but analysis has to associate a variety of tools to dress a best picture of the child’s health status, function and well-being what should help to determine objectives of treatment and evaluate outcome . The interest to use a validated available visual score associated to other validated evaluation tools may be underlined to complete and facilitate clinical practice.

To enhance quality of observation based assessment tools, it is important to know more details about the specific patient and clinician population involved. Association of the OGA scale to different evaluation tools in outcome studies may confirm its sensitivity .

Daily paediatric orthopaedic practice changes in time. New surgical techniques are introduced and the new treatment and evaluation strategies in CP patients cannot be ignored.

Therefore clinician’s educational content has to be reconsidered regularly. One time learned “how to observe” a patient, based on standardized observational gait analysis, decision making and follow-up is highly facilitated without the necessity of curve interpretations in technical reports. But consequently access to the logic of instrumented 3D-gait analysis or specific courses will also be facilitated for a larger proportion of clinicians, what will increase observational reliability.

1.5

Conclusion

EGS may be used with good reliability. Good clinical practice in CP associated to knowledge of clinical gait analysis allows better reliability. Observational gait analysis training before visual scoring is useful to enhance quality and reliability. EGS terms are related to instrumented gait analysis terms, which should be known by an observer who would like to use EGS in a clinical day-to-day practice. The EGS is a useful tool that should be associated for global assessment of the pathology of CP patients and for observational gait analysis teaching purposes. Validation work has to be continued comparing the EGS to other validated outcome evaluation tools in clinical and research practice.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’analyse quantifiée tridimensionnelle de la marche (AQM) fournit des mesures quantitatives lors de l’évaluation des patients marchants atteints de paralysie cérébrale (PC) lors du processus décisionnel, ainsi que lors de l’évaluation des résultats thérapeutiques .

Bien que l’AQM n’est pour le moment pas disponible universellement, elle peut être considérée comme l’évaluation de référence et il a été démontré qu’elle est un outil efficace d’évaluation clinique .

La marche pathologique de ces patients peut être décrite de façon globale en utilisant des scores extraits de l’AQM comme le Gillette Gait Index (GGI, anciennement Normalcy Index) basé sur une sélection de variables de l’AQM, considérés les plus pertinents pour des patients PC .

Mais un laboratoire complet d’analyse de mouvement n’est pas disponible dans toutes les institutions. Il est coûteux et exige un travail fastidieux de traitement des données et un haut niveau de compétence dans leur interprétation . De plus, les laboratoires bien équipés sont confrontés à un important flux de patients.

Le travail clinique quotidien peut être complété par l’introduction de différents outils d’évaluation, comme des scores fonctionnels, des outils d’évaluation de la qualité de vie et des scores d’activités de vie quotidienne. La classification internationale du fonctionnement, du handicap et de la santé (CIF) nous aide d’établir un cadre de l’évaluation globale des patients . Pour utiliser ce cadre conceptuel, il faut bien préciser les définitions des concepts et les placer dans un contexte clinique. La CIF introduit les concepts de structure et fonction, d’« activité » et de « participation » dans un contexte de facteurs personnels et environnementaux. Lors de l’évaluation par l’analyse de la marche on se place dans le cadre de l’évaluation de la « fonction » marche.

Les cliniciens en charge d’enfants PC marchant observent systématiquement la marche pour déterminer les troubles à traiter et pour évaluer ensuite les traitements proposés.

Par conséquent, l’analyse d’observation de la marche (AOM), une partie intégrante de l’analyse tridimensionnelle de la marche, peut être une aide intéressante en clinique courante, en particulier en utilisant des échelles standardisées.

D’abord, différents outils d’observation à « l’œil nu » ont été utilisés pour évaluer différents groupes de patients et pour évaluer les résultats thérapeutiques .

Pour surmonter les problèmes de l’évaluation de la marche à « l’œil nu », des outils spécifiques ont été élaborés afin de standardiser ces évaluations .

Néanmoins, en raison de la nature relativement subjective des AOM, un outil d’évaluation utilisé pour le partage de l’information clinique entre les cliniciens et pour la recherche multicentrique doit répondre au mieux aux critères de validité, de fiabilité, de sensibilité et de spécificité dont la définition des concepts est bien établit et homogène lors de la description des propriétés psychométriques des différents outils d’évaluation ( Fig. 1 ). Cet outil doit prendre en compte le contexte de la population des patients étudiés. Par conséquent, dans le cadre clinique du traitement d’une paralysie cérébrale, l’outil à choisir devrait être développé spécialement pour les enfants atteints de PC. Afin d’utiliser l’AOM comme outil d’évaluation objectif, différentes échelles d’observation ont été alors introduites pour améliorer la qualité de l’analyse et pour produire des données quantitatives comparables.

Au moment de la mise en place de l’étude présentée ici, l’EGS est l’instrument répondant au mieux à l’ensemble de ces critères .

L’EGS a été développé en tant que système visuel de notation, facile à utiliser, fiable, montrant une bonne corrélation avec les résultats d’analyse instrumentale de la marche, qui peut être utilisé pour évaluer les vidéos archivés.

L’association et la comparaison des données des observations et des analyses instrumentales de la marche est intéressante et une étude récente a validé l’EGS comme outil d’évaluation standard avec des corrélations significatives avec le GGI .

Les auteurs du score ont démontré une bonne fiabilité intra-observateur et interobservateur, ainsi qu’une bonne corrélation avec les mesures d’analyse de la marche instrumentale. En outre, le score était en mesure de détecter des modifications postopératoire après chirurgie multisite .

L’étude de la fiabilité de l’EGS et du Physician Rating Scale a montré pour les deux instruments une excellente fiabilité intra-observateur mais une mauvaise fiabilité interobservateur pour les enfants PC . Les auteurs recommandent que l’évaluation longitudinale d’un patient soit faite par un seul observateur.

Conformément à notre objectif d’introduire l’EGS comme outil de routine pour l’évaluation des résultats dans notre pays, nous avons à étudier les facteurs qui influencent la fiabilité intra-observateur et interobservateurs pour compléter les instructions fournies aux utilisateurs.

Par conséquent, le but de notre étude était d’évaluer la fiabilité intra-observateur et interobservateur de l’EGS obtenu par des praticiens expérimentés ou non dans l’analyse de la marche.

2.2

Matériel et méthodes

2.2.1

L’analyse d’observation de la marche

Une série de dix enregistrements vidéo archivés acquis durant une analyse de marche instrumentale ont été choisis au hasard et ont été examinés.

Les données de l’analyse de la marche ont été acquises en utilisant un système optoélectronique de six caméras avec des marqueurs passifs (ELITE, BTS, Milan, Italie) travaillant à une fréquence d’échantillonnage de 50 Hz au Centre d’analyse de mouvement des auteurs. Les sujets, équipés de marqueurs selon la description de Davis et al. , ont été invités à marcher pieds nus, à leur propre vitesse, sur une piste contenant trois plateformes de force Kistler.

Les dix patients, âgés de neuf à 16 ans, avaient un diagnostic de diplégie spastique. Les vidéos pour l’AOM ont été acquises simultanément en vue sagittale et coronale.

Huit observateurs ont examiné les dix enregistrements vidéo à deux reprises, avec un minimum de deux semaines entre les deux évaluations. Les huit observateurs ont été choisis dans différentes spécialités : trois chirurgiens orthopédistes pédiatres, un interne en chirurgie orthopédique, un neurochirurgien, un médecin rééducateur et deux kinésithérapeutes. Les observateurs ont évalué les vidéos dans un ordre aléatoire et en absence des résultats de la première lecture lors de la seconde. L’expérience clinique avec les patients PC et l’expérience de l’analyse de la marche de chaque observateur ont été notées.

Les directives fournies par les développeurs de l’EGS ont été traduites et fournies aux observateurs qui ont évalué chaque vidéo de patient en utilisant le système de pointage EGS ( Tableau 1 ) totalisés pour chaque membre inférieur, à six niveaux anatomiques : tronc, bassin, hanche, genou, cheville et pied dans le plan sagittal, transversal et frontal .