Abstract

Aim of the study

To assess the validity of the sitting position when testing lumbar braces for the maintenance of lordosis.

Patients and methods

Twelve young adult subjects participated in the experiment, in which they were seated on force platform. The four experimental conditions (with or without a brace and with or without enforced lordosis) were chosen in order to distinguish between the roles played by lordosis and the brace, respectively. The trajectories of the centre of pressure (CP) were analyzed and compared, in order to assess postural orientation and stabilisation processes.

Results

Although no effect was seen in terms of orientation, our data showed that use of a lumbar brace led to a notable reduction in CP displacement along the mediolateral and anteroposterior axes. Lordosis barely affected postural performance and only an increase in the mean CP velocity was observed. Lastly, an analysis of variance failed to reveal an interaction between the “lordosis” and “brace” factors.

Conclusion

A lumbar brace (in the absence or presence of lordosis) helps subjects to improve their sitting performance. In contrast to previous studies based on the standing posture, the fact that significant differences were found as a function of brace wear emphasises the discriminant power of the sitting position. This task should therefore be applied more widely in the development of more appropriate, validated equipment for lower back pain sufferers.

Résumé

Objectifs

Mettre en évidence la capacité de la station assise à servir de support pour le test d’une ceinture lombaire lordosante.

Patients et méthodes

Douze jeunes adultes ont participé à l’expérience qui consistait à se tenir assis en bougeant le moins possible sur une plateforme de force. Les quatre conditions expérimentales proposées (avec ou sans ceinture, avec ou sans lordose) avaient pour but de différencier le rôle de la lordose et de la ceinture. Les trajectoires du centre des pressions (CP) ont été analysées et comparées pour déterminer les processus d’orientation et de stabilisation posturales.

Résultats

Si aucun effet d’orientation n’est mis en évidence, le port d’une ceinture lombaire offre une réduction notable des déplacements du CP selon les axes médiolatéraux et antéropostérieurs. La mise en lordose n’affecte significativement que la vitesse moyenne de CP qui augmente. Enfin l’Anova ne révèle aucun effet d’interaction entre la lordose et le port d’une ceinture.

Conclusion

La ceinture lombaire, qu’elle soit lordosante ou non, permet une meilleure capacité de maintien de la station assise. Contrairement à des études précédentes menées en station debout, l’obtention chez des sujets sains de résultats significatifs selon qu’une ceinture est portée ou non révèle le pouvoir discriminant de la station assise. Cette dernière tâche pourrait donc être privilégiée dans l’objectif de tester ce type de matériel et ainsi permettre une meilleure adéquation vis-à-vis des besoins des patients.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The vertebral column displays three or even four curvatures in the sagittal plane. These curvatures vary in amplitude from one individual to another and differ in nature (the lumbar curvature is concave, for example). These curvatures appear to be essential for optimal sensory perception and good trunk motricity control. Indeed, specific braces have been designed and developed with a view to maintaining or even accentuating this lordotic lumbar curvature. However, the braces’ effects on postural behaviour need to be better defined in standardized laboratory tasks, such as the balance control and the position of certain spinal segments.

The role of physiological lumbar lordosis has been revealed with respect to several criteria. It has been shown that lumbar lordosis leads to a decrease in intradiscal pressure, rehydration of the intervertebral discs and thus a decrease in back pain . However, in a study of the sitting position, Claus et al. showed that lumbar lordosis was only maintained for a short time and then decreased or even disappeared over the long term. Although the maintenance of lordosis remains quite difficult, this posture presents a number of advantages. Hence, use of appropriate back brace may be one way of maintaining the benefits of lordosis over time.

Many researchers have already studied lumbar braces or belts which reduce the mobility of the vertebral column. In the evaluation of a new back belt, Chen reported a statistically significant increase in the trunk angle and L1-S1 angles (suggesting better postural maintenance). Electromyographic data revealed lower activation of the lower back muscles when wearing a brace , which translated into greater stability. Another study has shown that use of a lower back support in the sitting position enabled healthy subjects to maintain lumbar lordosis and increased the spinal disc height and sacral inclination . These results were recently confirmed in patients . Taking these results as a whole, it appears that lumbar braces can improve the maintenance of lordosis in the sitting position and that certain effects can be seen in both patients and healthy subjects.

The present study was prompted by the lack of objective tests for validating these orthopaedic products (especially those inducing lordosis). Our objective was to establish the validity of the sitting position for testing lumbar braces and highlighting the effects of lordosis. The back support brace tested here relies on a system of viscoelastic coils to maintain physiological lumbar lordosis. We hypothesized that the effects of wearing a brace are more likely to be visible in the sitting posture than in the standing position, in view of two major principles. The first concerns the total absence of leg compensation in the seated position; the subject’s balance will solely depend on the activity of the trunk muscles. The second concerns the intensity of the trunk muscle activity; the sitting position requires the spinal muscles to work harder than the standing posture does. Whereas maintenance of a relaxed, upright position requires between 2 and 5% of the spinal muscles’ maximal isometric strength, the sitting position requires between 3 and 15% . Several researchers have already used the sitting posture to evaluate the effects of a lumbar brace on postural control. Chen and then Cholewicki et al. evaluated the effects of a back belt by building their protocol around the sitting position. However, the belts used in these studies were not especially designed to help the wearer maintain lordosis. The subjects in our present study were healthy young adults without any back problems. This situation had several advantages. Firstly, behavioural variability is usually lower in healthy subjects than in patients. Secondly, it is possible to apply several different experimental conditions and increase the acquisition time (and thus further decrease behavioural variability), without running the risk of triggering an interaction with fatigue or pain. Lastly, the results in healthy subjects could be used as reference data for subsequent experiments in patients.

In as much as wearing a lordotic lumbar brace both induces and maintains lordosis (thus relieving both the active and passive ligaments in the lower back), it is important to distinguish between these two effects. We designed our protocol on this basis by including four different experimental conditions: (i) without a brace, (ii) without a brace but with forced lordosis, (iii) with a normal back brace and (iv) with a lordotic lumbar brace. Our starting hypotheses were that use of a brace would have a positive effect on postural control of the trunk, that this effect would be accentuated by a lordotic posture and that the sitting position would provide more visible results. In posturographic terms, better control should translate into reduced displacement of the centre of the pressure (CP).

1.2

Methods

1.2.1

Subjects

Twelve volunteers (six women and six men, aged between 20 and 23) participated in the study. The subjects’ mean (standard deviation) height was 171 (9) cm, the mean sitting height was 91 (4) cm and the mean weight was 62 (9) kg. None of the subjects had a history of neurological disorders, trauma or chronic or occasional back/leg pain.

1.2.2

Patients

The subjects were tested on a triangular force platform (the PF01 model from Equi + , Aix-les-Bains, France) fitted with a thick and supposedly non-deformable steel plate. The signals from three dynamometric sensors (placed under each of the platform’s summits) were amplified and digitized prior to recording on a microcomputer at a sampling frequency of 64 Hz.

The lordotic lumbar brace tested here (supplied by Ormihl Danet, Villeurbanne, France) is an adjustable back support ( Fig. 1 ). An abdominopectoral rod strongly restricts spinal flexion and lumbar lordosis is created by a series of viscoelastic coils. The brace is also fitted with several straps, which enable the tightness to be adjusted to suit the wearer’s anatomy.

1.2.3

Procedure

Subjects sat on the force platform in a standardized position, with the contact area corresponding to the full surface area of the buttocks and three-quarters of the thigh surface area. The legs and feet were unsupported and the arms were held folded in front of the chest ( Fig. 1 ). The subjects were instructed to close their eyes and move as little as possible, while maintaining normal breathing.

The protocol included four conditions (performed in random order): (i) a normal back brace (CN), (ii) a lordotic lumbar brace (CL), (iii) no brace and a straight back (REF) and (iv) no brace and forced lordosis (RL). Six 32 s trials were performed for each condition, with 10 s of rest between trials (since no true fatigue was expected to appear). Subjects had 5 min of rest between each condition, during which time the brace was put on or taken off.

The braces were always adjusted to fit the subject by the same investigator, in order to obtain reproducible tightening of the straps and positioning of the front rod. The elastic coils were arranged so as to obtain maximum lordosis and strong compression.

The homogeneity of the forced lordosis was ensured by the arrangement of the viscoelastic coils and precise tightening of the elastic bands. After noting the bands’ initial lengths in the absence of tension, our principle was to shorten the elastic bands by 5 cm, the lower straps by 2 cm and the upper straps by 1 cm. Lordosis was only checked visually but the investigator was able to reject trials in which this criterion was not meet.

1.2.4

Data processing

The subject’s postural orientation was analyzed in terms of the mean CP displacements along the mediolateral (ML) and anteroposterior (AP) axes. These parameters enabled us to detect possible effects of inclination.

For the stability analysis, the “ellipse with a confidence interval” , the variances of the CP’s position along the ML and AP axes and the mean CP velocity were recorded. The data were examined statistically in an analysis of variance with repeated measures, with “lordosis” and “brace” as factors. The significance threshold was set to p < 0.05.

1.2.5

Results

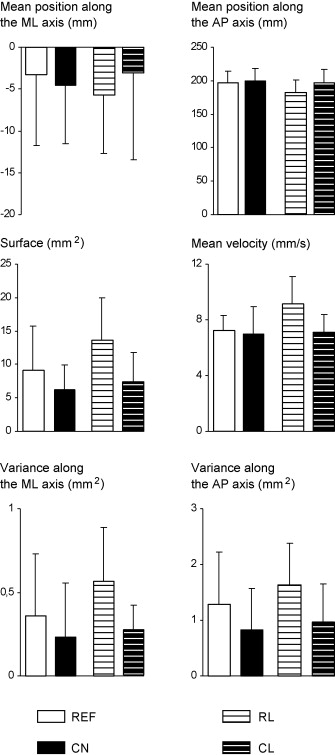

There were no statistically significant effects on the mean CP position along the ML axis (F(1.44) = 0.075; p > 0.05) or the AP axis (F(1.44) = 2.82; p > 0.05). Hence, in the sitting posture, there was no effect of the inclination provoked by use of a lumbar brace.

Significant effects on the other parameters revealed that use of a lumbar brace modifies the balance control processes. There were statistically significant changes in the ellipse’s area (F(1.44) = 7.59; p < 0.01), the CP’s variances along the AP and ML axes (F(1.44) = 5.8 and F(1.44) = 6.82 respectively, with p < 0.05) and the mean CP velocity (F(1.44) = 6.79; p < 0.05). Hence, use of a lumbar brace when sitting makes the upper body more stable.

In view of the corresponding bar charts ( Fig. 2 ), it may be possible to explain this “brace effect”. When comparing the REF condition with the CN condition and then RL with CL, one can see that use of a lumbar brace leads to a significant decrease in all the parameters other than the mean CP position along the AP and ML axes. Wearing a brace (with or without lordosis) thus improves stability and balance control.

With regards to the “lordosis” factor, only one statistically significant effect was found: mean CP velocity (F(1.44) = 4.97; p < 0.05). In fact, lordosis increases the velocity ( Fig. 2 ). None of the other parameters were significantly modified.

By comparing the REF condition with the RL condition in Fig. 2 and then CN with CL, one can see that lordosis tended to increase all the criteria other than the mean CP position along the AP axis. This effect was independent of the presence or absence of a lumbar brace.

Lastly, the results of the ANOVA showed that there was no interaction between the “lordosis” and “brace” factors; the lordotic lumbar brace did not have a greater effect than the normal lumbar brace. There was nevertheless a slight trend towards worse results with lordosis.

1.3

Discussion

The prime objective of the present study was to determine the effect of wearing a lumbar brace on postural control in the sitting posture in healthy subjects. This approach enabled us to highlight two important points: (i) use of a brace does not have any significant effects on upper body stability and (ii) lordosis tends to perturb balance in the sitting posture, although this perturbation is not statistically significant in most cases (except for the mean CP velocity, p < 0.05). Moreover, the effects measured in a stable, seated position can be compared with those reported by Van Daele et al. for an unstable sitting position; our results emphasize the utility of the “stable” seated position for revealing effects related to changes in control of the lower part of the spine.

1.3.1

Balance control is improved by the use of a brace

The present study included four sets of conditions; two involved the use of a brace (CN and CL) and two did not (REF and RL). Our statistical analyses revealed that use of a lumbar brace led to greater stability and a better balance control. These results validated our starting hypothesis and are in agreement with the findings of several other studies. In fact, a seated-posture study of a new (but non-lordotic) lumbar brace in healthy subjects (with foot supports) showed that the sitting position was more stable when the brace was worn . The non-lordotic brace reportedly had a stabilizing effect, just as the lordotic lumbar brace did here. Our study can also be compared with Cholewicki’s work based on electromyographic data (because CP displacements mainly result from neuromuscular activities). In the present study, we observe a decrease in the CP displacements during brace use. This finding is in agreement with the decrease in neuromuscular activity reported by Cholewicki . These various findings emphasize the primarily stabilizing role of the brace when sitting. Brace use enables long-term maintenance of lordosis (sitting for 60 minutes) . In contrast, another study showed that in the absence of a brace, lordosis could only be maintained for a relatively short time and then tended to disappear completely . Hence, lumbar braces may be a way of reinforcing the maintenance of lordosis and prolonging “brace effects”. Nevertheless, it is difficult to compare the latter results with those of our present study, given the differences between the protocols (foot supports and forearm supports).

The idea that a lumbar brace can usefully facilitate the maintenance of lordosis has also been mentioned by Cholewicki et al. . The objective of the latter study was to estimate the theoretical reduction in trunk muscle activity over 3 weeks of brace use in the sitting and standing positions in healthy subjects. The results showed that wearing a lumbar brace induced a decrease in trunk muscle activity. This decrease may reflect the greater stability induced by the back brace. However, it must be borne in mind that unlike our present data, Cholewicki et al.’s results were not statistically significant. Nevertheless, it has been shown that that a static contraction at 5% of the maximal voluntary force induces muscle fatigue and pain ; hence, even a slight decrease in muscle contraction could markedly facilitate trunk movement control.

All these various results are in agreement with our data and reinforce the hypothesis whereby “brace effects” persist over time.

The same lordotic lumbar brace has already been tested in the standing position in healthy subjects and back pain sufferers . In each of these studies, the lordotic brace was compared with: (i) a reference condition in the absence of a brace and (ii) a non-rigid brace. It is important to note that the results were only significant in the low back pain sufferers. In the present case, use of the brace led to a significant decrease in the mean CP displacement on the AP axis, the CP velocity and the surface area of the ellipse, when compared with the reference condition. It is interesting to relate the previous work to our present study because standing or seated postural behaviours are dependent for the ML axis but not for the AP axis . In healthy subjects, Lee and Chen compared the effects of a flat lumbar brace in the standing position and in erect and slumped sitting positions. The authors reported that the effect of lumbar brace use on spinal column angles depended on the subjects’ posture. When the subjects wore the lumbar brace in the standing and normal sitting positions, the L1-S1 angles increased (except for L5-S1 in a normal sitting position). However, brace use did not modify these angles in the erect sitting position. In the sitting posture in healthy subjects, our results show that a lumbar brace induces a significant reduction in the CP velocity and ellipse area but also provokes forward inclination. In view of the observed reduction in variances along the ML and AP axes, wearing a lordotic lumbar brace may enable better balance control in healthy subjects. Similar effects might be observable in lower back pain sufferers. Nevertheless, given that lower back pain sufferers and healthy subjects do not use the same balance control strategies , one can hypothesize that complex interactions (related to pain and apprehension) might occur and would modify the effects observed in healthy individuals.

1.3.2

Lordosis, postural stability and balance control

Our results showed that lordosis has only slightly beneficial effects on balance and thus invalidated our starting hypothesis. Lordosis slightly perturbs the subject’s stability because of the (non-significant) increase in most of the standard parameters taken into account. Only the CP velocity increased significantly and the mean position along the AP axis was the only parameter to decrease with lordosis. According to Asseman et al. , an increase in CP velocity mainly reflects greater muscle activity and thus greater energy expenditure. This is in line with Nachemson and Morris’s study , which showed that maintenance of lumbar lordosis requires more intense trunk muscle activity. Hence, lordosis may lead to greater energy expenditure and thus more fatigue. The weakness of the effects obtained for the “lordosis” factor can be explained by hip flexion which, in the sitting posture, leads to lumbar cyphosis and counters the maintenance of lordosis .

Our study looked solely at kinetic effects and not biomechanical effects. Although no kinetic advantages were observed (other than velocity), it has been suggested that use of a lumbar brace has biomechanical advantages . The resulting trunk hyperextension may decrease the load on the vertebral column and rehydrate the spinal discs. Makhsous et al. reported that lower back support was advantageous in the sitting position in healthy subjects. A similar conclusion was reached recently for low back pain sufferers . Lumbar support decreases the sitting load and the CP’s ML and AP displacements. The presence of lumbar support also increases the pressure on the lower part of the chair back, which facilitates the maintenance of lordosis. The results obtained by Makhsous et al. suggest that the effects of reduced ischial support and enhanced lumbar support are similar in individuals with and without lower back pain. Hence, data from healthy subjects may be applicable as a benchmark for subsequent studies in patients.

In conclusion, our results confirm the positive impact of lumbar brace use on postural control in the seated position. However, lordosis does not appear to be an additional determinant factor in these effects. This is explained probably by the fact that lordosis is difficult to achieve in the sitting position. Our observation of significant results for healthy subjects in the sitting position (rather than in the standing station) nevertheless reveals the discriminant nature of this task. Hence, the sitting position should be favoured in protocols designed to test the effects of medical devices (such as lumbar braces) and to monitor any corresponding long-term changes.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Ormihl-Danet company for providing the lumbar braces and wish to thank the manuscript’s two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Dans le plan sagittal, la colonne vertébrale est pourvue de trois, voire quatre courbures. Elles sont plus ou moins marquées selon les individus et sont de nature différente, la courbure lombaire étant par exemple concave. Ces courbures semblent essentielles pour une perception sensorielle optimale et, par suite, un contrôle performant de la motricité du tronc. C’est dans cette perspective de maintien, voire de renforcement, de cette courbure lombaire lordosante qu’ont été imaginées et développées des ceintures spécifiques. Leurs incidences comportementales nécessitent toutefois d’être mieux définies au travers de tâches de laboratoire standardisées comme le contrôle de l’équilibre ou de la position de certains segments.

Le rôle de la lordose lombaire physiologique a été mis en évidence selon plusieurs critères. Il a été montré qu’une lordose lombaire entraînait une diminution de la pression intradiscale et une réhydratation des disques intervertébraux et donc une diminution des douleurs dorsales . Cependant, dans une étude concernant la position assise, Claus et al. ont montré que le maintien d’une lordose lombaire n’était possible que dans un temps restreint car la lordose tendait à diminuer à long terme, voire à disparaître. La lordose présente donc des avantages, même si son maintien reste relativement difficile. Une ceinture lombaire lordosante pourrait être un moyen de la maintenir dans le temps avec les avantages qui l’accompagnent.

Les ceintures lombaires qui réduisent la mobilité de la colonne vertébrale ont déjà intéressé beaucoup de chercheurs. Chen , dans une étude évaluant une ceinture lombaire innovante, montre une augmentation statistiquement significative des angles tronc-horizontale et L1–S1, suggérant un meilleur maintien postural. Des données électromyographiques montrent une moindre activation des muscles du bas du dos , ce qui se traduit par une plus grande stabilité grâce au port de la ceinture. Une autre étude a montré qu’un support au niveau du bas du dos en position assise chez des sujets sains permettait le maintien de la lordose lombaire, augmentait la hauteur des disques intervertébraux et diminuait les douleurs dorsales . Ces résultats ont été confirmés plus récemment chez des patients . Au vu de toutes ces études, il apparaît que la ceinture lombaire lordosante pourrait être un moyen de renforcer le maintien de la lordose en position assise et que des effets puissent s’observer chez des patients comme des sujets sains.

La présente étude part du constat de l’absence de tests objectifs permettant de valider ces produits orthopédiques, et en particulier ceux induisant une lordose. Notre objectif est de mettre en évidence la capacité de la position assise à servir de support pour tester des ceintures lombaires et à mettre en avant les effets de la lordose. La ceinture lombaire testée ici est une ceinture qui permet de conserver la lordose lombaire physiologique grâce à un système de pelotes viscoélastiques. Si des effets liés au port de cette ceinture sont susceptibles d’être mis en évidence, on peut faire l’hypothèse que ceux-ci seront beaucoup plus visibles en station assise qu’en station debout, au regard de deux grands principes. Le premier concerne l’absence totale de compensation avec le membre inférieur, ainsi l’équilibre de l’individu ne dépendra dans ce cas que de la seule activité des muscles du tronc. Le second concerne l’activité des muscles du tronc, la position assise est plus contraignante que la station debout pour les muscles spinaux : si la position debout relâchée requiert 2 à 5 % de la force isométrique maximale de ces muscles spinaux, la position assise en requiert 3 à 15 % . Avant nous, plusieurs chercheurs ont utilisé la station assise afin d’évaluer les effets d’une ceinture lombaire sur le contrôle postural. Chen , puis Cholewicki et al. ont évalué les effets d’une ceinture lombaire en construisant leur protocole autour de la position assise. Les ceintures utilisées ne déterminaient toutefois pas de lordose.

Les sujets choisis pour notre étude sont des sujets sains sans problèmes au niveau du dos. L’avantage de travailler avec de tels sujets est double. Tout d’abord, la variabilité comportementale est normalement moindre que chez des patients. De plus, il est possible de multiplier les conditions et d’augmenter les temps d’acquisition (et donc de diminuer la variabilité comportementale) sans risque de voir apparaître une interaction avec la fatigue ou la douleur. Enfin, les résultats obtenus pourront être utilisés comme éléments de référence pour les expériences ultérieures avec des patients.

Dans la mesure où le port d’une ceinture lombaire lordosante conduit à la fois à une lordose forcée et à un maintien (soulageant ainsi les ligaments actifs et passifs de la partie basse du dos), il importe que ces deux effets soient dissociés. C’est à partir de là que notre protocole a été construit avec quatre conditions expérimentales (sans ceinture, sans ceinture avec lordose forcée, avec ceinture lombaire normale, avec ceinture lombaire lordosante). Les hypothèses sont que le port d’une ceinture aurait un effet positif sur le contrôle de la position du tronc, que cet effet serait renforcé avec une posture lordosante et que la position assise permettrait d’obtenir des résultats plus visibles. Dans un cadre posturographique, ces meilleurs contrôles se matérialiseraient par une réduction des déplacements du centre des pressions (CP).

2.2

Méthodes

2.2.1

Sujets

Douze participants volontaires (six femmes et six hommes), âgés de 20 ans à 23 ans, ont participé à l’expérience. La taille moyenne (écart-type) debout des sujets était de 171 (9) cm et la taille assise moyenne de 91 (4) cm. Le poids moyen des sujets était de 62 (9) kg. Les sujets étaient dépourvus d’antécédents neurologiques ou traumatologiques et n’avaient aucune douleur chronique ou temporelle au niveau du dos et des membres inférieurs.

2.2.2

Patients

Les personnes ont été testées sur une plateforme de force triangulaire (Equi ± PF01, France) formée d’une plaque en acier rigide suffisamment épaisse pour être supposée indéformable. Les signaux issus des trois capteurs dynamométriques, placés sous chacun des sommets de la plateforme, étaient amplifiés, puis numérisés grâce à une carte d’acquisition avant d’être enregistrés sur un micro-ordinateur à une fréquence de 64 Hz.

La ceinture lombaire lordosante (Ormihl Danet, Villeurbanne, France) est un corset d’immobilisation vertébrale à effet modulable ( Fig. 1 ). Elle est supposée limiter fortement la flexion du rachis par la présence du mât abdomino-pectoral et crée la lordose lombaire grâce à des pelotes viscoélastiques. Elle est dotée de plusieurs sangles qui permettent d’adapter le serrage à la morphologie des sujets.