Immediate Care

Sports first aid

Assess the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC).

Assess and monitor level of consciousness.

Direct the casualty on to the appropriate agency.

Keep within recognized first aid guidelines.

We all have a ‘Duty of Care’ (Good Samaritan), but will have a different standard of care, whether doctor, nurse, physiotherapist, etc.

In children, there is an additional responsibility. Contact parents immediately—you are ‘locum parentis’—responsible for their care and management and must have written consent to ‘administer’ medication.

Roles and responsibilities of first aider

Assess: what has occurred.

Protect: self and others.

Identify: nature of illness/injury.

Treat: by severity and safety.

Transport: remove to care.

Accompany: remain with casualty.

Report: to doctor or paramedic.

Isolate: to prevent cross-infection.

Secure: valuables and clothing.

Inform: family.

Recording incidents

Health & Safety Executives (HSE) have a form to record.

Name and address of casualty.

Date and time of incident.

Details.

Witnesses.

Injury.

Treatment.

Disposal.

Include your name and contact details.

First aid facilities at venues

It is important to know the venue and the key staff, including the location of the first aid room, medical help, and the particular emergency procedures for the venue. Remember when telephoning for help to give the exact location and try to meet the ambulance where possible. This is especially important at a large venue.

The Taylor Report has set criteria for safety at sports grounds with specific advice regarding doctors, ambulances, etc., depending on the expected crowd size.

Make sure that the first aid room is open and has the following:

Telephone: with emergency contact numbers.

Large, clean room with good lighting.

Stretcher.

Couch, pillows, and blankets.

Hot and cold running water with soap and towels.

Ice and bags.

First aid kit.

Approach to the acutely ill or injured athlete

Best achieved by a pre-planned (and trained) team approach, with each team member aware of their individual roles and responsibilities. However, in many sporting situations the first aider will be the only suitably trained individual.

Prioritize if there is more than one casualty. Multiple casualties are common especially in contact sports. A quiet casualty is a potentially dead casualty. Remember the possibility of injury to or illness in the spectators.

Direct visualization of the injury mechanism will help to prioritize or give a clue as to diagnosis.

The general approach can be summarized as:

Establish scene safety.

Rapid primary survey with resuscitation and immediate treatment of life- and limb-threatening injuries.

A detailed secondary survey.

Initiation of definitive care based on the above.

Crisis management: the primary survey

DRS ABC

D = Danger.

R = Response.

S = Shout or Send for help.

ABC = Assess and treat as required.

Danger could include hazards such as electricity, water, and height. Remember that in a sporting situation the most common danger is the game and its participants so always:

STOP THE GAME!

For ABC see Basic Life Support, p. 6

Disability

Some authors consider Disability within the primary survey (ABCD). This consists of a brief neurological assessment to assess the level of consciousness of the casualty. This best achieved and noted by using the AVPU scale (see Box 1.1), rather than the more detailed, but complicated Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS; may be used by health professionals). This assessment allows a decision regarding urgent transfer to hospital for a more detailed assessment, especially when the neurological signs are deteriorating.

Possible spinal injury

Any unconscious casualty or one who complains of neck pain, numbness, weakness, or paralysis should be assumed to have a neck injury until proved otherwise. This is particularly important where the mechanism of injury is suggestive of potential cervical damage. Such situations include a fall from height (diving, horse riding, climbing, etc.), injuries at speed (motor racing, etc.) or where the cervical spine is seen to hyperextend, flex, or rotate (rugby, American football, etc.).

Exposure during the primary survey

Remove enough clothing to allow detailed examination (remember not to remove headgear in suspected spinal injury except for resuscitation). Preserve casualty dignity as much as possible and avoid hypothermia by covering with a blanket/clothing.

There is a delicate balance between the time required for an extensive primary survey and the ‘load and go’ approach of early transport for more definitive care. This decision will be based on the nature of the injuries, experience of those present, the need for more definitive care, such as need for surgery, advanced airway management, vascular access, distance to secondary care, and mode of transport available. The casualty should be constantly monitored during this assessment and ongoing care including ABC and AVPU.

Basic life support

Introduction

The publication of the 2010 UK Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2010 marks the 50th anniversary of modern cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). In 1960 the first paper on survival of cardiac arrest by 14 patients by application of closed chest cardiac massage was published, and later that year the combination of chest compressions and rescue breathing was introduced.

Following an initial assessment of the possible danger to the casualty and those carrying out the resuscitation and the response of the casualty, basic life support (BLS) comprises:

Airway maintenance.

Rescue breathing.

Chest compression.

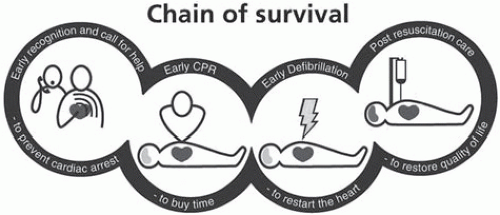

Chain of survival

A cardiac arrest is the ultimate medical emergency with the chances of survival considerably improved if appropriate steps are taken to deal with the emergency. It is now recognized that a chain of interventions contribute to a potentially successful outcome of a cardiac arrest—the ‘Chain of survival’ (Fig. 1.1).

The 4 steps of the chain are:

Early recognition and call for help to prevent cardiac arrest

Early CPR

Early defibrillation

Early advanced life support (ALS)

International consensus

Resuscitation guidelines in the UK are set by the Resuscitation Council (UK), which is itself a member of the European Resuscitation Council. There is now a desire to seek consensus among all areas of the world and as a result the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) was formed in an attempt to ensure that guidelines for resuscitation are uniform in all countries.

Purpose of BLS

Maintain adequate ventilation and circulation until means can be obtained to reverse the underlying cause of the arrest—in practice by defibrillation.

BLS is a ‘holding operation’. On occasions, particularly when the primary pathology is respiratory failure, it may itself reverse the cause and allow full recovery.

Failure of the circulation for 3-4 min (less if the victim is initially hypoxic) will lead to irreversible cerebral damage.

Assessment of the carotid pulse is time-consuming and leads to an incorrect conclusion (present or absent) in up to 50% of cases. For this reason, training in detection of the carotid pulse as a sign of cardiac arrest is no longer recommended for non-healthcare persons.

The safety of both rescuer and casualty are paramount, but the risk to the rescuer during CPR is minimal. While there have been isolated reports of transmission of infections such as tuberculosis, transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) during CPR has never been reported.

Barrier devices with one-way valves have been shown in laboratory studies to prevent transmission of oral bacteria from the victim. Rescuers should therefore take all appropriate safety precautions if the casualty is known to have a serious infection. Compression-only CPR may be appropriate in this instance.

In non-asphyxial cardiac arrest as blood oxygen remains high initially, ventilation is less important than compressions. Thus, the priority is to start with compressions.

Jaw thrust is not recommended for lay rescuers as it is difficult to learn and perform, and best left for more experienced personnel in cases of suspected neck injury.

2010 Guideline changes

The Resuscitation Council recently updated the BLS Guidelines to reflect the fact that an interruption in chest compressions is common and associated with a reduced chance of survival for the victim. Ideally, compressions should be given continuously, while giving ventilations independently— possible only in ALS with an advanced airway in place. Compression-only CPR will increase the number of compressions and eliminate pauses, but at the expense of any ventilation. New guidelines emphasize the importance of the correct depth and rate of compressions.

Guideline changes

When obtaining help ask for an automated external defibrillator (AED) if available.

Compress the chest to a depth of 5-6cm at a rate of 100-120/min (previously 100/min).

Give each rescue breath over 1s, rather than 2s.

Do not stop to check the victim or discontinue CPR unless the victim starts to show signs of regaining consciousness, such as coughing, opening his eyes, speaking or moving purposefully and starts to breathe normally.

Teach CPR to laypeople with an emphasis on chest compression, but include ventilation as the standard, particularly for those with a duty of care.

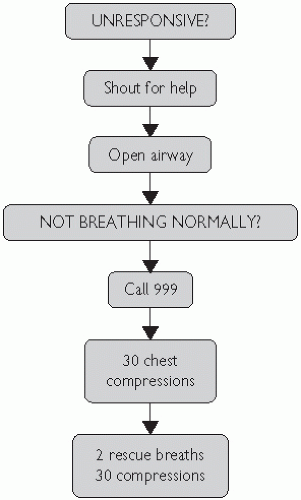

Sequence of events for BLS (Fig. 1.2)

Check for danger (rescuer and victim).

Check for response—squeeze and shout ask ‘Are you all right?’

If response, leave in position in which found or place casualty in the recovery position. Try to find out any information about the casualty, send for help if required, and reassess regularly.

If no response:

Shout for help.

Turn casualty on his back.

Open the airway—head tilt, chin lift, and remove any visible loose objects from mouth. Leave well-fitting dentures and gum-shields.

If cervical spine injury suspected then use jaw lift instead of head tilt.

Keeping the airway open Look, listen, and feel for normal breathing for no more than 10s. If in doubt, act as if the casualty is not breathing.

Look for chest movement.

Listen at the casualty’s mouth for breath sounds.

Feel for air on your cheek.

If breathing, place casualty in the recovery position, send for help if required, and reassess regularly.

If not breathing:

Send for help and ask them to bring an AED if available. If on your own use your mobile or nearby phone to call for an ambulance or when no other option exists go for help at this stage and return to continue BLS. In some circumstances it is recommended that 1 min of CPR is given before a lone rescuer goes for help (see p. 9). If the casualty is not breathing do not check for signs of circulation but proceed immediately to commence chest compressions.

Kneel by the side of the casualty.

Place the heel of one hand in the centre of the casualty’s chest and place the heel of the other hand on top of the first. Less emphasis on exact hand placement is encouraged in the revised guidelines to prevent further time being lost prior to commencing compressions.

Interlock fingers of both hands, extend arms vertically above the sternum, and depress the sternum 5-6cm × 100-120/min without losing contact between your hands and the sternum. Pressure should be on the centre of the sternum, not the lower sternum,

ribs, or upper abdomen. Compression and release should take an equal amount of time.

Combine chest compressions with rescue breaths:

After 30 compressions open the airway again (head tilt/chin lift)

Pinch the soft part of the nose with thumb and index finger, allow casualty’s mouth to open, but maintain chin lift, take a normal breath, place your lips around the casualty’s mouth ensuring a good seal, and blow steadily into the mouth watching for the casualty’s chest rise—the breath should take 1s—this is an effective rescue breath. Repeat for a second rescue breath – the 2 breaths should take no more than 5s.

Return hands to the correct position on the sternum and give a further 30 compressions.

Continue with chest compressions and rescue breaths in a ratio of 30:2.

Do not interrupt resuscitation. Do not stop to recheck the casualty unless he shows signs of life (as described above).

If the rescue breaths do not result in the chest rising as in normal breathing then:

Check the casualty’s mouth and remove any visible obstruction.

Recheck there is adequate head tilt and chin lift.

Check adequate seal around the casualty’s mouth.

Do not attempt more than 2 breaths each time before returning to chest compressions.

Continue resuscitation until:

More qualified help arrives and takes over.

The victim shows signs of life

Exhaustion.

Compression-only CPR

Use if untrained or unwilling to give rescue breaths.

Give at a continuous rate of 100-120/min.

Do not stop unless casualty shows signs of regaining consciousness (as above).

When to go for help

When there is more than one rescuer, then one should go for help immediately. With a single rescuer and if the casualty is an adult, then assume the cause is cardiac and go for help before commencing cardiac compressions when no other option exists, e.g. using nearby or mobile phone.

It may be worthwhile performing resuscitation for 1min before going for help if:

The cause is respiratory.

Trauma.

Choking.

Drug or alcohol intoxication or poison.

Drowning or extreme cold.

The casualty is a child.

Two-person resuscitation

Send one person for help as the second commences resuscitation.

Work as a coordinated team on opposite sides of the casualty.

Maintain airway at all times.

Ensure a smooth and quick transition between ventilation and compressions. In particular, ensure the minimum of delay without interruption of chest compressions.

Further points re BLS

Use of oxygen: no evidence of benefit except in drowning and will interrupt chest compressions.

Mouth to nose ventilation: effective alternative if casualty’s mouth seriously injured or cannot be opened.

Bag-mask ventilation: requires considerable skill and particularly difficult for single rescuer. Reserve for experienced rescuer or where risk of poisoning.

Importance of chest compressions: when teaching BLS it is important to emphasize the importance of the compression element of resuscitation, particularly the new rate of 100-120/min, the increased depth of 5-6cm and minimizing the interruptions in compressions.

If the casualty vomits during resuscitation (seen particularly in drowning), turn the casualty on their side ensuring the head is towards the floor and the mouth open to allow the vomit to drain away. Ensure the mouth is clear of debris before turning onto back, ensuring a clear airway and recommencing CPR.

Fig. 1.2 Adult BLS algorithm. Reproduced with kind permission from the Resuscitation Council UK (Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2010). |

Resuscitation of children

Changes in resuscitation of children have resulted from both new scientific evidence (limited) and the need to maintain simplicity to assist teaching and retention.

The fear of causing harm to a child as a result of resuscitation is unfounded. For ease of teaching and retention, laypeople should be taught that the adult sequence should be used for children who are not responsive and not breathing.

Guideline changes

While ventilation is a vital component of asphyxial arrest rescuers who are unable or unwilling to do this should be encouraged to perform compression-only CPR.

Pulse palpation for 10s is unreliable for determining effective circulation even when performed by health professionals and should not be the sole determinant of the need for CPR. Pulse checks are not part of layperson CPR.

It has been shown that chest compression is frequently too shallow. As a result the guidelines have changed from ‘approximately one-third’ to ‘at least one-third’ of the antero-posterior (AP) diameter of the chest. The guidelines encourage advising ‘don’t be afraid to push too hard’. Use 2 fingers for an infant under 1 yr.

To maintain consistency, the rate of compression is as in adults— 100-120/min.

Use of AEDs in children

More evidence of the safe and successful use of AEDs in children less than 8 years has become available since the last guideline change in 2005.

AED manufacturers now supply purpose-made pads and programmes which limit the output to 50-75J.

If no paediatric adjusted machine is available, an adult AED may be used.

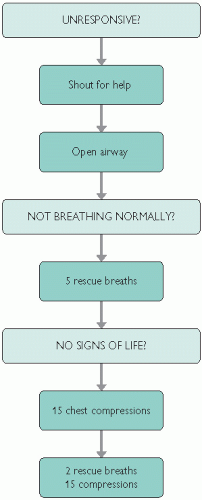

BLS sequence (Fig. 1.3)

For laypeople and those health professionals who have no experience of paediatric resuscitation the adult 30:2 sequence should be used with the following modifications:

Give 5 initial rescue breaths before starting chest compression.

If the responder is alone, perform 1min of CPR before going for help.

For 2 or more health professionals performing CPR, who have experience of paediatric resuscitation a ratio of 15:2 should be used, i.e. which utilizes more rescue breaths.

Fig. 1.3 Paediatric BLS algorithm. Reproduced with permission from the Resuscitation Council UK. (Resuscitation Council Guidelines, 2010). |

Advanced adult life support

Introduction

Heart rhythms associated with cardiac arrest can be divided into two groups:

The main difference between the two is the need for defibrillation in those with VF/VT. All other actions including chest compressions, airway management and ventilation, venous access, administration of adrenaline, and correction of contributing factors are common to both.

Where any of these contributing factors are present, resuscitation will require specific intervention to treat/reverse the cause.

Shockable rhythms (VF/VT)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree