History and Evolution of External Fixation

Bradley P. Abicht

Thomas S. Roukis

Introduction

Physicians and surgeons have utilized external fixation as a method for stabilizing, reconstructing, and treating osseous and soft tissue pathology for millennia. The materials and methods of fixation devices began with rudimentary supplies such as wooden splints, screws, and rods. Over time, with the growth of new medical knowledge and engineering of superior implements, the quality of materials has evolved, resulting in more advanced constructs. However, despite improved materials, the principles of external fixation have remained essentially unchanged.

First Use

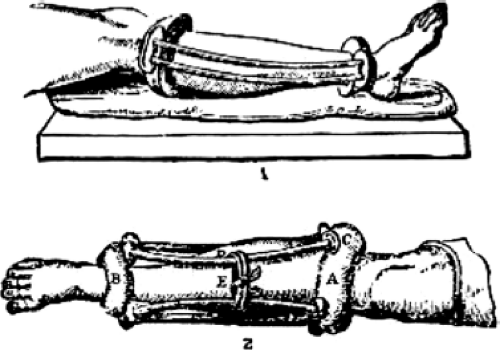

The first documented use of a true external fixation device dates back to 377 BC when Hippocrates described a rudimentary device used to treat closed tibial fractures1 (Figure 1.1). The device consisted of four wooden rods from a cornel tree that spanned between proximal and distal Egyptian leather rings. Taught leather cuffs with sockets were placed at the ankle and knee. Over-lengthened flexible wooden rods were then bent and positioned in such a manner as to create distraction and realignment capable of maintaining length and establishing anatomical alignment. The general principle set forth in this primitive device by Hippocrates would remain with time, although his rudimentary device would undergo significant metamorphosis throughout history.

Timeline

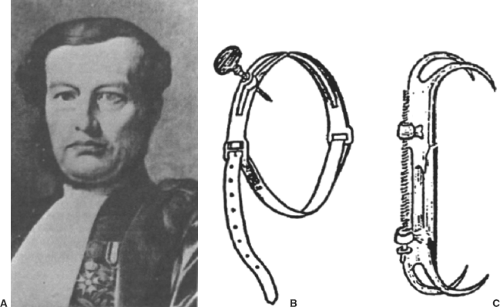

Although the first documentation of external fixation dates back more than 2,400 years, most authors agree that the true meaningful beginning is credited to the famous professor of surgery Jean-Francois Malgaigne (1806–1865)2,3 (Figure 1.2). In 1840 he described a “point,” which more correctly was a spike introduced into the tibia stabilized by straps used for immobilization and prevention of tibial fracture displacement. In 1843 he engineered a “claw” that resembled a C-shaped clamp. This device had two transcutaneous prongs at each end with a screw between them that when turned would approximate the four metal prongs thereby reducing and maintaining patellar fractures. Malgaigne did document two problems intrinsic to external fixation devices, “First, to let the patient have access to the screw; second, to require a substantial force to tighten and loosen the screw, a force which caused the whole appliance to move and was very painful for the patient.”4 Despite advancement in technology associated with external fixation devices over the ensuing 160 years, these observations by Malgaigne unfortunately still hold true today.

Following Malgaigne, other surgeons developed external fixation constructs employing similar principles. In 1850 Ph. Rigaud (1805–1881) of Strasbourg developed a device that utilized two wooden screws united by a string.5 This external fixation device was used to treat olecranon fractures. The stability of this particular device was further enhanced in 1870 by L.J.B. Berenger-Feroud (1832–1900) who innovatively joined the screws with a wooden bar.6 Additionally, he was known for describing an external fixation device useful for mandibular fracture stabilization in his classic work

“Traité de l’immobilisation directe des fragments osseux dans les fractures.”3 Early external fixation constructs continued to be modified and developed, but it was not until the innovations by Parkhill and Lambotte that the first readily available devices were available for general use.

“Traité de l’immobilisation directe des fragments osseux dans les fractures.”3 Early external fixation constructs continued to be modified and developed, but it was not until the innovations by Parkhill and Lambotte that the first readily available devices were available for general use.

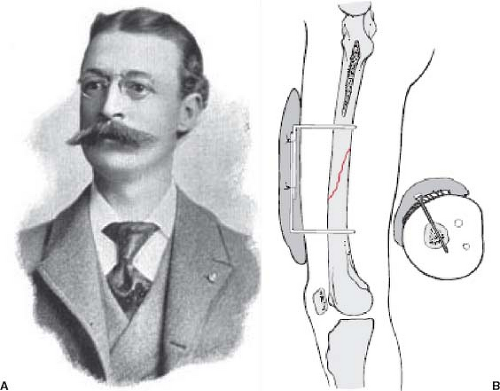

Clayton Parkhill (1860–1902) was an American anatomist and surgeon born in Vanderbilt, Pennsylvania, who later settled in Denver, Colorado, where he became professor of surgery and dean of the medical school at the University of Colorado (Figure 1.3). Apart from his leadership roles and

accomplishments as a great anatomist and surgeon, he was known for his inventions in several areas, one being specific to external fixation. Parkhill believed that his device was useful for, as he described, “… more accurate fixation of the bones, both after resection for cases of pseudoarthrosis and for malunion, and also for fractures with a tendency to displacement, particularly if they be compound.”7 In 1894 he designed a “bone clamp,” most consistent with a unilateral type of external fixation device, which consisted of four fracture spanning wing plates with an offset hole at one end.7 Four wooden screws were transversely placed adjacent to the fracture site, two proximal and two distal, equidistantly offset from the fracture line. A nut to each respective screw then joined the wing plates. The exposed screw end took on the shape of a square, permitting it to be turned by a church key. Three sizes were developed to accommodate differential lengths of long bones being treated. The strength of this construct was achieved through joining the four wing plates together as one unit, thereby imparting stability and immobilization across the fracture site. The clamp was also made of steel and heavily plated with silver, taking advantage of its antiseptic properties.2,3,7 Parkhill eventually reported on 14 patients successfully treated with his external fixation device, for which he proclaimed a 100% cure rate. He also noted the following observations regarding his device, “We claim for this instrument: first, that it may be easily and accurately adjusted, and prevents both longitudinal and lateral movements between the fragments; second, that nothing is left in the tissues which might reduce their vitality and lead to pain or infection; third, that no secondary operation is necessary; fourth, that no method has ever before given 100 percent of cures.”7

accomplishments as a great anatomist and surgeon, he was known for his inventions in several areas, one being specific to external fixation. Parkhill believed that his device was useful for, as he described, “… more accurate fixation of the bones, both after resection for cases of pseudoarthrosis and for malunion, and also for fractures with a tendency to displacement, particularly if they be compound.”7 In 1894 he designed a “bone clamp,” most consistent with a unilateral type of external fixation device, which consisted of four fracture spanning wing plates with an offset hole at one end.7 Four wooden screws were transversely placed adjacent to the fracture site, two proximal and two distal, equidistantly offset from the fracture line. A nut to each respective screw then joined the wing plates. The exposed screw end took on the shape of a square, permitting it to be turned by a church key. Three sizes were developed to accommodate differential lengths of long bones being treated. The strength of this construct was achieved through joining the four wing plates together as one unit, thereby imparting stability and immobilization across the fracture site. The clamp was also made of steel and heavily plated with silver, taking advantage of its antiseptic properties.2,3,7 Parkhill eventually reported on 14 patients successfully treated with his external fixation device, for which he proclaimed a 100% cure rate. He also noted the following observations regarding his device, “We claim for this instrument: first, that it may be easily and accurately adjusted, and prevents both longitudinal and lateral movements between the fragments; second, that nothing is left in the tissues which might reduce their vitality and lead to pain or infection; third, that no secondary operation is necessary; fourth, that no method has ever before given 100 percent of cures.”7

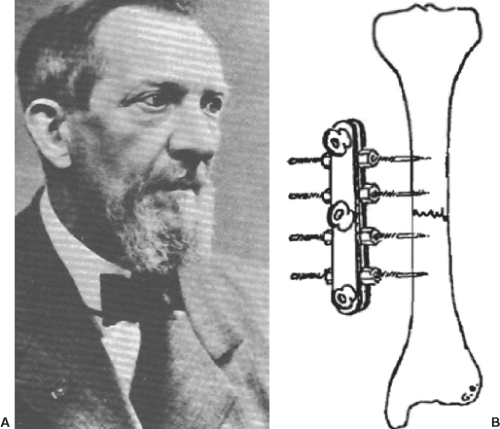

In 1902, Albin Lambotte (1866–1955), the pioneer of modern osteosynthesis, expanded on the concept of unilateral external fixation by joining two longitudinal plates clamped to the sides of four fully threaded metal transverse screws (Figure 1.4). He detailed his device in his classic publication, “Chirurgie operatoire des fractures,” describing the use of external fixation on upper and lower extremities, as well as the hand. He was the first to utilize threaded pins and reports the advantages of his external fixation device, including the ease of use, timeliness of application, and rigidity stabilizing osseous fragments. This inherent rigidness permitted passive and active mobilization of the adjacent joints. Due to his unique design, Lambotte also stated that this device was conducive to dressing application of open wounds, as well as, could be removed without difficulty after osseous consolidation. He repeatedly attributed the decreased incidence of amputation, which previously seemed inevitable, to the use of his external fixation device.8

External fixation devices continued to develop with Alessandro Codivilla (1861–1912) and Fritz Steinmann (1872–1932) issuing their contributions at the beginning of the 1900s. Codivilla, in 1902, introduced a method of skeletal traction and was credited for the first use of full-pin splintage with external bars used in distraction osteogenesis and treatment of chronic lower extremity deformities.9 This was controversial and in direct contrast to Steinmann, as the literature varies on who is rightfully credited for the introduction of pin traction. Nevertheless, in 1907, Steinmann directed two pins into the femoral condyles to apply skeletal traction. He enhanced skeletal traction by redirecting the reduction force directly onto the bone. The insertion of Steinmann’s pins at the time was accomplished by exerting longitudinal force on one end

of the pin with a hammer. Later, in 1916, he perfected the “through-and-through” technique for skeletal traction. Prior to this development, external plaster strips were being utilized to transmit distracting forces onto bone through the soft tissues, but often resulted in complications including severe pain, skin necrosis, and failures revealed by radiograph analysis.10,11 The German surgeon Martin Kirschner (1879–1942), in 1909, utilized chromed, non-blazed piano-wire from 0.7 to 1.5 mm in diameter, which was inserted directly into the bone with the goal of minimizing soft tissue or osseous trauma, and also to keep the wire rigidly fixed to avoid transverse wire movement during skeletal fixation.10 He intuitively developed a horseshoe-shaped instrument to perfect the tension principle, which prevented lateral movement and instability of the thin wires that occasionally led to pin-track infection and osteomyelitis. The eponym Kirschner (K)-wire continues to be commonly utilized to this day, although its first documentation was by Müller in 1931.12 The K-wire has evolved from its initial introduction with skeletal traction, and has progressed to an instrument in fracture reduction, and has revolutionized the treatment of fracture-dislocations as a guidance tool for other implants or internal fixation devices (i.e., cannulated materials).

of the pin with a hammer. Later, in 1916, he perfected the “through-and-through” technique for skeletal traction. Prior to this development, external plaster strips were being utilized to transmit distracting forces onto bone through the soft tissues, but often resulted in complications including severe pain, skin necrosis, and failures revealed by radiograph analysis.10,11 The German surgeon Martin Kirschner (1879–1942), in 1909, utilized chromed, non-blazed piano-wire from 0.7 to 1.5 mm in diameter, which was inserted directly into the bone with the goal of minimizing soft tissue or osseous trauma, and also to keep the wire rigidly fixed to avoid transverse wire movement during skeletal fixation.10 He intuitively developed a horseshoe-shaped instrument to perfect the tension principle, which prevented lateral movement and instability of the thin wires that occasionally led to pin-track infection and osteomyelitis. The eponym Kirschner (K)-wire continues to be commonly utilized to this day, although its first documentation was by Müller in 1931.12 The K-wire has evolved from its initial introduction with skeletal traction, and has progressed to an instrument in fracture reduction, and has revolutionized the treatment of fracture-dislocations as a guidance tool for other implants or internal fixation devices (i.e., cannulated materials).

In addition to the substantial contributions of Codivilla, Steinmann, and Kirschner, several additional advancements of external fixation are noteworthy for discussion. E.W. Hey Groves (1872–1944), in 1912, developed an external fixation device that provided the option for compression or distraction, accomplished through a “turn-buckle” attached to pins.13 Lorenz Böhler (1885–1973), in 1928, refuted controversial thinking at the time by demonstrating that the insertion of Steinmann pins was a relatively benign process, and that excellent results were achieved with pins-and-plaster for treatment of fractures.14 This established new standards and redefined acceptable treatment for fracture care.

In the 1930s, Otto Stader (1894–1962), an American veterinarian, developed an external fixation device that would come to be known as the “Stader splint.” He used this to treat fractures in a series of over 1,200 canines. The device was composed of two half-pin units inserted directly into each fracture fragment held together by a connecting bar. Advantages of his external fixation device included the ability to allow complete ambulation after fixation, no discernable pain, did not require adjunctive casting, and did not require separate reduction device.14 His successful results in the veterinary arena translated over to human fracture treatment when his device was first used in 1937 and was utilized on embattled soldiers during World War II.

Around the same time period, several other surgeons pioneered external fixation devices or modified previously designed constructs. Roger Anderson, in the 1930s, created an external fixation device that also used half pins. He believed that it is necessary to supplement the construct with a cast and prohibited weight bearing during the first few weeks following external fixation application. Similarly, Herbert H. Haynes used a half-pin device, but reinforced it with plaster of Paris. Intuitively, he inserted pins through both cortices, which inherently increased the rigidity and subsequent stability of the external fixation construct.2,14 Alfred Schanz (1868–1931), Jean-Paul Lamare, and Gustav Riedel all documented the principle of inserting half pins at an angle to each other and bridging the units with metal bars. In a similar fashion to Haynes, Henri Judet described increasing stability of external fixation constructs by inserting pins through both cortices in addition to the use of multiple half-pin units.2 The works of these previous surgeons were then once again revolutionized by a German-born doctor, Raoul Hoffman (1881–1972).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree