Historical Perspective

Holly Tyler-Paris Pilson

Eben A. Carroll

THE HISTORY OF NONOPERATIVE FRACTURE TREATMENT

Before the development of antiseptic principles and surgical techniques by Joseph Lister in 1865, the mainstay of treatment for most orthopaedic fractures centered around nonoperative management, including splinting, casting, traction, and bracing. Immobilization of fractures was carried out with whatever tools and materials were available at the time. Fracture union and prevention of deformity came at the expense of prolonged immobilization with its resultant sequelae. Early fracture surgery evolved to allow and encourage bony union and prevention of malunion while avoiding the complications of long-term immobilization. The emphasis on mobilization during the healing process was espoused in the founding principles of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen, or “the AO.” Its initial philosophy focused on anatomic reduction and soudure per primam or primary bone healing often at a biologic cost. As fracture surgery evolved, the importance of soft tissue preservation and the primary importance of biology led to techniques which facilitated healing and function and were less invasive to bone biology.

Splinting and Casting

Early examples of nonoperative fracture management can be traced back to the ancient Egyptians. Archaeologic artifacts of fractured extremities splinted with longitudinal wooden boards were discovered by A.C. Mace during the Hearst Egyptian expedition of the University of California in 1903.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7

Prior to the development of plaster-of-Paris and modern day plaster techniques, an Arab physician named Rhazes described a recipe for a casting material using clay gum mixtures, flour, and egg whites.8,9 Variations of this recipe, including the addition of lime, honey, pork fat, vinegar, and powder of Armenian clay or plaster were concocted up through the late 18th century.3,8, 9 and 10 The benefit of this method of immobilization touted by Rhazes Athuriscus was that “… it will be much handsomer and will not need to be removed until the healing is complete.”8

In 1852, the plaster-of-Paris bandage, derivates of which are still used today, was introduced by a Russian military surgeon, Antonius Mathijsen.11 This revolutionized the stabilization of healing fractures, providing a material which was durable and could be maintained for the duration of healing. Many subsequent methods of immobilization were invented including the copper limb curirasse described by Heister12 and what Malgaigne called “the great machine of La Faye.”13,14 The drawback of these extensive and heavy devices, however, was that they essentially confined the healing patient to the bed for the entirety of their rehabilitation. In turn, Seutin devised the amidonné, or starched bandage,15 allowing for earlier mobilization of the fractured extremity. Hence the debate over immobilization versus early mobilization of the fractured extremity was born. Most European surgeons favored total immobilization, with others such as Sir James Paget and Lucas-Championnière favoring Seutin’s déambulation regimen.16 In 1907 Championnière wrote, “the necessity for immobilization is only relative … [W]hile authors attach great importance to the immobilization of a compound fracture, we find here that with small movements and an apparatus moderately immobilizing, consolidation goes on well, and no inflammatory complications result.”16

Traction

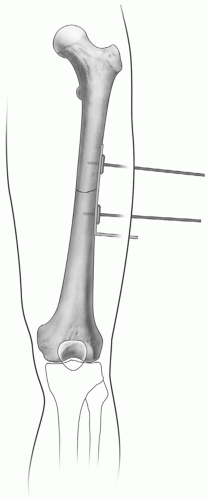

Descriptions of traction applied for the treatment of fractures can be found as early as AD 130 in the writings of Galen.2,17 He described an extension apparatus, or glossocomium (Fig. 1.1), used to temporarily treat fractured extremities until splinting could be performed by turning a handle to provide distraction. Continuous traction intended for primary fracture treatment can be found in the early writings of Guy de Chauliac (1300 to 1367);17,18 however, it was not widely practiced until the mid-19th century. Borrowing from the traction techniques of Bardenheuer, Albert Hoffa of Wurzburg published in his book of fractures and dislocations in 1888 the use of traction for many different types of fractures including those of the femur and humerus.19 Josiah Crosby of New Hampshire also described the use of continuous skin traction using a combination of adhesive plaster secured with a spiral bandage and weight applied to the end for the management of a femur fracture, an open tibia fracture and in two cases of clavicle fractures in children.20 Codivilla of Bologna was the first known to apply skeletal traction via the use of an intraosseous pin, with Fritz Steinman popularizing the technique in the treatment of acute fractures.21 Steinman, frustrated with the complications of skin traction, described using two pins driven through the femoral condyles to pull in-line traction for midshaft femur fractures in 1907.22 Two years later, Martin Kirschner of Greifswald would describe skeletal traction using wires of a much smaller diameter.22

Figure 1.1 A traction apparatus called the glossocomium, described by Galen, illustrated from the writings of Ambroise Paré (1564). |

Traction, though more likely to decrease the risk of malunion in healing fractures, came at the expense of prolonged periods of immobilization, as well as the risks inherent to the placement and maintenance of traction devices themselves. Aside from the obvious external drawbacks of immobilization, including bed sores, soft tissue and bone infections, and delay in return to work or war, there

were other less conspicuous effects including internal signs of decompensation, such as muscle atrophy.23

were other less conspicuous effects including internal signs of decompensation, such as muscle atrophy.23

Recognizing these limitations, Professor George Perkins of London advocated for straight simple in-line traction through a proximal tibial pin in the 1940s and 1950s, which would also allow for early mobilization of the knee using a Pyrford traction system.15,24 Also aware of the difficulties of immobilization in healing fractures was Dowden, who in the opening sentence of his 1924 article wrote, “The principle of early active movement in the treatment of practically all injuries and in most inflammations will assuredly be adopted before long… .”* Both Perkins and Dowden were among the many early advocates of mobilization of all joints of the injured limb, believing it to be even more important than precise skeletal reduction. To such pioneers it became clear that a more sophisticated means of maintaining function while the healing process occurred was needed.

EARLY OPERATIVE TECHNIQUES

Even before the introduction of aseptic surgical techniques, the internal fixation of fractures was documented as early as the 1770s. Although controversy exists regarding the first account of internal fixation of a fracture, most authors attribute it to two surgeons from Toulouse, Lapujode, and Sicre, who were said to have performed ligature, or the wire suturing of bone.25 Screws, which undoubtedly had many applications in the mid 1800s, made their way into the repertoire of orthopaedic implants in the 1840s. Cücuel and Rigaud described the use of screw fixation in the application of traction for a depressed sternal fracture as well as for fixation of an olecranon and a patellar fracture.15

Early fracture surgery was mostly influenced by the development of three new technologies: Anesthesia by Morton (1846), Antisepsis by Lister (1865), and Radiography by Röntgen (1895).26 Joseph Lister, most known for his antiseptic surgical principles, first applied these techniques using carbolic acid in the treatment of compound fractures in 1867.27 His success in drastically reducing complications, namely death, from postoperative wound infection, and subsequent improvements in aseptic techniques, opened the door for not only fracture surgery, but also all surgical procedures in general.

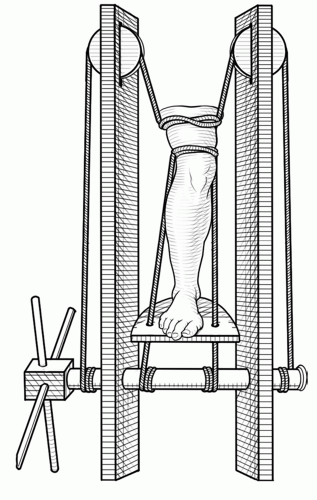

The concurrent evolution in design of orthopaedic implants kept pace with the first accounts of plate fixation described by Hansmann in the late 19th century. In his 1886 article, he described his technique for applying a malleable plate in the fixation of acute fractures, pseudarthroses, and the reconstruction of a humeral enchondroma.15 For fracture treatment, his technique involved applying the plate to span the fracture site, with screws purchasing each fracture fragment and projecting far out through the skin, for more easy removal, typically at around 4 to 8 weeks (Fig. 1.2). The end of the plate was also bent at a right angle with projection through the skin. In 1903, George Guthrie documented further use of plate fixation by Estes and Steinbach.15 Estes used a nickel steel plate fixed to the bone with ivory pegs, whereas Steinbach utilized silver, a highly favored implant material due to its believed antibiotic properties. Ten years later Albin Lambotte (1866 to 1955) of Belgium, regarded by many as the father of internal fixation, coined the term osteosynthesis

in his classic book “Chirurgie Opératoire des Fractures” in 1913.15,28 He manufactured most of his own instruments and implants, including plates and screws for internal fixation as well as an external fixation device similar in principle to the ones in use today.28

in his classic book “Chirurgie Opératoire des Fractures” in 1913.15,28 He manufactured most of his own instruments and implants, including plates and screws for internal fixation as well as an external fixation device similar in principle to the ones in use today.28

Another great visionary in the field of internal fixation, William Arbuthnot Lane of London, had become quite frustrated with the results of fracture management in the late 19th century. He came to understand that the firmest union did not universally lead to a good functional outcome; that a patient whose foot was in the slightest degree of malalignment could have terrible function, even if complete union was achieved.29, 30 and 31 He thus became greatly focused on the need for accuracy and maintenance of a good reduction, especially of articular injuries.

Both Lane and Lambotte were almost contemporaneously describing intramedullary screw fixation for femoral neck fractures in 1905, although various forms of intramedullary devices had been previously described by Koenig, Cheyne, Gillette, Dieffenbach, V. Langenbeck, Nicolaysen, Delbet, Schone, Muler-Meernach, Thompson, and Bircher, to whom the earliest account is attributed in 1866.19,28,32, 33 and 34 Gerhardt Küntscher, in collaboration with Professor Fischer and engineer Ernst Pohl at Kiel University in Germany, were credited with the development of the first long metallic intramedullary device, as we know it today, in the 1930s.34,35 Further modifications by the AO group and collaboration between Klemm, Schellmann, Grosse, and Kempf resulted in the development of the current generation of interlocking nailing systems.

Many of the later implant designs of Lane and Lambotte were most likely inspired by Sherman, who introduced his own series of plates and screws in his 1926 article, drawing attention to the superior fixation obtained with parallel, threaded, self-tapping fine pitched screws.36 This more superior fixation, he believed, would be firm enough to permit early mobilization and rehabilitation, a theme which set the foundations for the AO era.36,37

THE AO ERA

In 1958, the establishment of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen, or the AO, by 13 men: Maurice Müller, Hans Willenegger, Robert Schneider, Martin Allgöwer, Walter Bandi, Ernst Baumann, August Guggenbühl, Willy Hunzicker, Walter Ott, René Patry, Walter Schär, Walter Stähli and Fritz Brussatis, revolutionized the operative management of fractures worldwide.

Although not part of the AO itself, the framework upon which its principles and concepts were formed can be attributed in part, if not entirely to the life and work of Robert Danis. Danis, regarded as the father of modern osteosynthesis, was trained as a general surgeon with interests in thoracic and vascular surgery, but later became intrigued by the internal fixation of fractures.15 Undoubtedly of the mind-set of the “mobilizers,” he stressed the following three aims of a satisfactory osteosynthesis in his 1949 publication, Théorie et Pratique de l’Ostéosynthèse.38

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree