Pain.

Limp.

Discomfort leading to reduced walking/running distances.

Snapping or clicking sensation of the hip.

Stiffness/reduced range of motion.

Deformity.

Examine gait:

Look for evidence of asymmetry or biomechanical abnormality.

Scars.

Sinuses.

Swellings/masses.

Muscle wasting.

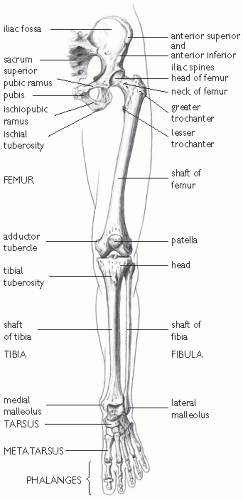

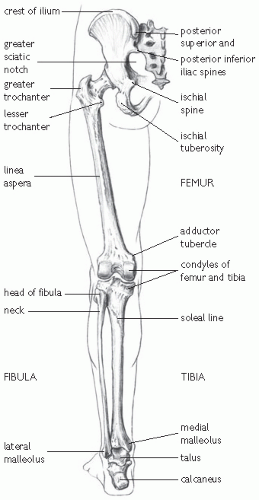

Apparent limb length by measuring the distance from umbilicus to medial malleolus.

True limb length discrepancy is noted by measuring the distance from anterior superior iliac spine (or any ipsilateral fixed bony point) to medial malleolus after squaring the pelvis (unmask the fixed abduction or adduction deformity of the affected limb so that both anterior superior iliac spine and medial malleolus are levelled, and place the normal limb in a similar position).

Skin temperature.

Tenderness over the greater trochanter and in the groin area.

Palpate swellings/masses if present.

Flexion range of 0-130°.

Extension of 0-10°.

Abduction of 0-45°.

Adduction of 0-40°.

IR of 0-30°.

ER of 0-60°

Table 21.1 Hip joint: movements, principal muscles, and their innervation. Reproduced with permission from Mackinnon P and Morris J (2005) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

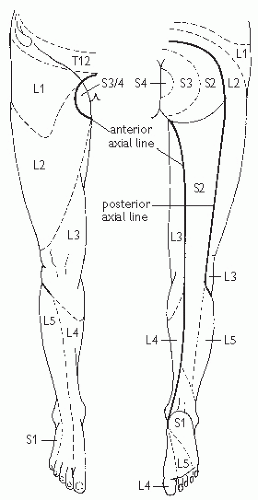

Table 21.2 Main spinal nerve root supplying the movements of the lower limb. Reproduced with permission from Mackinnon P and Morris J (2005) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pain on flexion, adduction, and IR of the hip joint occurs with anterior superior tears.

Pain on passive hyperextension, abduction, and ER occurs with posterior tears.

Pain moving the hip from a position of full flexion of the hip with ER and full abduction, to extension, abduction, and IR occurs with anterior tears.

and exerts a downward pressure on the knee with the other hand, while rotating the hip internally. The test is positive if there is pain or tightness. If the sciatic nerve is compressed (piriformis syndrome), the patient experiences radicular-like symptoms.

Plain radiographs, CT, MR, and bone scan, and arthroscopy are helpful to confirm clinical diagnoses.

Severe pain, with obvious swelling and deformity.

Unable to move the limb.

Beware of hypovolaemic shock; up to 1.5L of blood may be lost into the thigh.

Check and document the presence of distal pulses and the neurological status of the affected limb.

Radiographs to include both hip and knee joints. The incidence of ipsilateral femoral shaft and femoral neck fractures is 3%.

Manage shock:

Two wide bore venous cannulae (brown- or grey-coloured).

Hartmann’s solution is preferred.

Urinary catherization.

Cross-match 2-4units of blood.

Analgesia.

Adequate splint (Thomas splint).

Femoral fractures generally require a surgical treatment, with different techniques according to the type of fracture and patient characteristics.

Gold standard is early closed intramedullary nailing for closed fractures (<24h).

Fix femoral neck first, if present.

Open fractures need emergency debridement and stabilization.

Paediatric femoral shaft fractures can be managed with traction.

Fat embolism.

Infection.

Delayed union requiring dynamization of interlocking nail.

Non-union may need reamed exchange nailing.

Malunion (may need corrective surgery).

Separation of the epiphysis from the metaphysis with disruption of the complete physis.

Separation of part of the physis, with a portion of metaphysis attached to the epiphysis (Thurston-Holland sign).

Fracture of the epiphysis extending into the physis.

The fracture traverses metaphysis, physis, epiphysis and the articular cartilage.

This injury is end-on crush of the physis. Diagnosis is retrospective as radiographs are normal at initial presentation. MRI can be useful for the diagnosis.

Immediate anatomical reduction either by gentle closed or open methods, and adequate fixation (conservative or surgical) aid restoration of function and normal growth.

If the entire physis is affected, bone growth and, therefore, length is retarded. If a part of physis is affected, angular deformity may result.

Deep aching pain in the groin that may radiate to the knee.

Pain is progressive, occurs with activity, and resolves with rest.

Pain becomes constant if activities are continued without modification.

May present with a limp.

May be no specific site of point tenderness.

Range of motion of the hip, particularly IR, may be limited due to pain.

Walking, static running, or hopping on the affected extremity often reproduces the pain.

Plain radiographs may be negative.

MRI is more sensitive, specific, and accurate than a bone scan in identifying a femoral neck stress fracture.

Tension (type I) and displaced (type III) fractures should be referred urgently to an orthopaedic surgeon for internal fixation.

Internal fixation aids early rehabilitation and return to sports.

Compression (type II) can be managed conservatively with non- or partial weight-bearing depending on pain and analgesia. The patient may start non-impact activities once pain-free.

Avascular necrosis.

Non-union (with conservative management).

Varus deformity (with conservative management).

Displacement (with conservative management).

Any of the above complications may lead to inability to return to pre-injury performance levels.

A gradual progression in the intensity and duration of all conditioning activities is crucial in the prevention of stress fractures.

A useful rule of thumb is that an increase in training volume (distance) or intensity should not exceed 10% per week.

Lateral hip pain, occasionally radiating along the distal lateral thigh.

May be associated with snapping or clicking sensation.

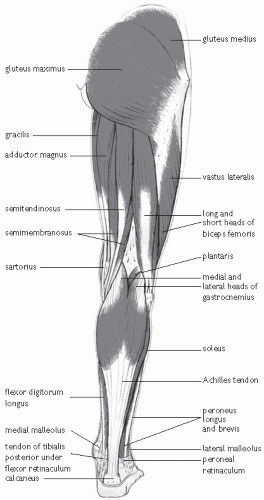

Point tenderness over the greater trochanter may be associated with crepitus on hip flexion and extension.

Pain at the extremes of hip rotation, abduction, or adduction (trochanteric)

Pain of contraction of hip abductors against resistance (trochanteric).

Pseudoradiculopathy: pain radiating down the lateral aspect of the thigh (trochanteric).

While diagnostic criteria have been proposed, their sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value have not been established.1

These criteria propose that lateral hip pain and tenderness around the greater trochanter must be present in combination with 1 of the following:

Pain at the extremes of rotation, abduction, or adduction.

Pain of contraction of the hip abductors against resistance.

Pseudoradiculopathy: pain radiating down the lateral aspect of the thigh.

Stress fractures.

Gluteus medius tendinopathy (dancers).

Lumbosacral radiculopathy.

Avascular necrosis.

Osteoarthritis.

Septic bursitis

Radiographs may help rule out other conditions.

Rest.

Ilio-tibial band and tensor fascia lata stretching.

Gluteal muscle strengthening.

Anti-inflammatory drugs.

Iontophoresis.

US.

Injection of local anaesthetic (5mL of 1% lignocaine 10mg/mL) into the point of maximal tenderness.

Flexion and extension of the knee may produce a crepitus.

Pain is worse during weight-bearing flexion and extension. Pain is typically worse at the 30° while flexion is occurring.

Reduction of activity.

Oral anti-inflammatories.

Ice, heat, US, and/or electrical stimulation.

Stretching exercises to address any excessive ITB tightness.

The optimum treatment is physiotherapy in combination with analgesic/anti-inflammatory medication.

Local anaesthetic and corticosteroid injections repeated twice at two weekly intervals may be helpful in resistant cases

Weight-bearing should be limited until the patient regains good quadriceps muscle control and 90° of pain-free knee motion.

Functional rehabilitation and non-impact sports are allowed when the range of motion has reached 120°, and there is no residual muscle atrophy.

Return to full activity: normal strength and range of motion (3 weeks). More severe injuries may have a longer recovery time.

Myositis ossificans development depends on the severity of the initial injury. It is more likely with repeated trauma. This process may appear histologically similar to osteosarcoma, but the history is usually distinct and the periphery of a myositis ossificans lesion is mature. (Myositis ossificans, p. 580).

Loss of range of motion and loss of functional outcome.

The least differentiated tissue lies in the central zone.

In the middle or intermediate zone, the osteoid is more organized and separated by a loose cellular stroma.

The outer zone is the most mature consisting of well-formed bone which may form a shell around the entire lesion. Cartilage formation may also be present.

6-8 weeks, a lacy pattern of new bone forms around the periphery of the mass. Complete maturation is usual in 5-6 months.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree