Hemiarthroplasty with and without Biologic Glenoid Resurfacing for Glenohumeral Arthritis with an Intact Rotator Cuff

Eddie Y. Lo

Wayne Z. Burkhead

DEFINITION

Glenohumeral osteoarthritis (OA) occurs with the progressive degeneration of articular cartilage.

Hemiarthroplasty (HA) is the prosthetic replacement of the humeral side without placing a polyethylene spacer on the glenoid surface.

Biologic resurfacing involves concentric reaming of the glenoid, with or without biologic tissue interposition over the articular surface.

ANATOMY

Glenohumeral joint includes the bony articulation and the static/dynamic soft tissue components.

The bony articulation includes the glenoid and humeral head. This is supported by static ligamentous structures, including the glenohumeral ligaments, joint capsule, and capsulolabral complex.

The dynamic structures include the four rotator cuff tendons. They maintain the glenohumeral joint alignment via balanced muscular forces. If this balance is lost, the humeral head is at risk of anterior, posterior, or superior translation.

The short head of the biceps tendon inserts on the coracoid process and is extra-articular. The long head of the biceps tendon, however, inserts on the supraglenoid tubercle, which is intra-articular but extrasynovial. Its biomechanical function in the shoulder remains controversial.

PATHOGENESIS

The development of OA is the chronic degeneration of articular cartilage through the intricate involvement of genetic, metabolic, biochemical, biomechanical, and social factors. Most of this is discussed in prior chapters, but the key points will again be elucidated.

Cartilage is an aneural structure, so the pain from OA arises from the noncartilaginous structures of the shoulder.

The inflammatory component of the pain is often associated with the capsular synovitis.

The mechanical component of the pain can be associated with the abnormal biomechanical forces on the bone.

During the development of arthritis, the osteochondral junction as well as the osteophytes become infiltrated with neurovascular structures, becoming a source of pain generator.26 Abnormal biomechanical forces on this subchondral bone is symptomatically felt as pain.

Substance P, cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) molecules can be identified in the subchondral bone as biochemical mediators of pain.21

Arnoldi et al1,2 compared patients with pain versus those without pain and found that pain symptoms correlated with development of high intraosseous pressure. If this pressure is relieved via osteotomy, the pain can be decompressed.

Intraosseous hypertension can then lead to decreased interstitial fluid flow, decreasing the nutrient supply to the chondrocytes, and inducing chondrocyte apoptosis.

NATURAL HISTORY

Primary OA usually occurs with no antecedent event, whereas secondary OA results from another coexisting problems such as previous micro- and macrotrauma, chronic instability, massive rotator cuff tear, or avascular necrosis. If the primary causes are not treated, OA will progressively worsen over time.

The most common wear pattern in OA is the posterior wear. As OA progresses, the posterior wear can exacerbate, eventually leading to humeral head subluxation. Clinically, these patients have higher revision rates and worse function, even after undergoing total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA).14

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients typically present with chronic, insidious pain with or without an acute exacerbation event.

Another common complaint is stiffness or decreased passive range of motion. The stiffness symptom can be temporal with worst symptoms in the morning, with improvement by midday.

On examination, patients usually have decreased active and passive range of motion. During examination, loud clunks or crepitus can be felt or heard.

Patients generally present with good rotator cuff strength, but one needs to distinguish between true weakness versus weakness secondary to pain. An effective diagnostic tool is local anesthetic injection intra-articularly, which would relieve patient’s pain symptoms and allow the practitioner to truly evaluate cuff strength.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Standard anteroposterior, axillary, and scapular Y radiographs of the shoulder are routinely obtained. These are reviewed to confirm the diagnosis of OA with intact rotator cuff.

The four signs of OA include subchondral sclerosis, subchondral cyst, joint space narrowing, and osteophyte formation.

If the integrity of the rotator is in question, advanced imaging including computed tomography (CT) arthrogram or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be obtained.

CT scans may be helpful in assessing concentric versus eccentric glenoid wear. Severity of wear can be noted for intraoperative adjustment of glenoid version.

Full-length humeral x-rays of both sides can be helpful if there is significant humeral bone loss. The length of bone loss can be calculated based on side-to-side comparison.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Inflammatory arthritis

Chondrolysis

Adhesive capsulitis

Rotator cuff tear

Cuff tear arthropathy

Infection

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The first-line treatment for OA is nonoperative, which includes life modification, physical therapy, and pain management.

Physical therapy can help maintain joint mobility and strength but adds little benefit to long-term symptom relief.25

Pain medications can include a combination of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or opioid medications.

Cortisone injection can be a useful adjunct in treatment of the inflammatory component of shoulder pain. The exact number of injections, frequency, and end point in treatment is dependent on the patient’s age, degree of progression, and overall health.

Hyaluronate injection has shown recent promise in treating osteoarthritic knee pain.4 However, in recent studies comparing hyaluronate to steroid, there has been no significant difference in clinical benefit noted.7

There have been no published comparative studies evaluating the efficacy of surgery versus placebo or other nonsurgical options.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The gold standard surgical treatment for glenohumeral arthritis with an intact rotator cuff is TSA. TSA has been shown to be superior to HA in reliably reducing pain, improving mobility, and overall function in patients with primary arthritis.

Edwards et al10 found that TSA was superior to HA in treatment of OA with adjusted Constant score of 96% for TSA and 86% for HA.

The only level 1 randomized clinical trial by Gartsman et al12 demonstrated that TSA provided greater pain relief and internal rotation than HA; however, given the limited patient number, no significant difference in patient outcomes were identified.

Radnay et al22 performed a meta-analysis including 1952 patients and mean follow-up of 43.4 months. The superiority in clinical outcomes (pain, range of motion, and satisfaction) were confirmed. They also found that 1.7% of glenoid components required revision, whereas 8.1% of HA required revision for pain.

Sandow et al24 evaluated their prospective cohort of 13 HA and 20 TSA at minimum of 10 years follow-up. They found that 42% of the TSA were pain-free, whereas 0% of the HA were pain-free. In addition, there were 31% of the HA patients who required revision, compared to 10% of the TSA patients.

There are, however, situations where placement of a TSA is suboptimal, including rotator cuff deficiency and glenoid deficiency. Another relative contraindication is the use of HA in treatment of OA of young patients, where the expectation is that the glenoid component will inevitably loosen over their lifetime.

In treating patients 55 years old or younger, Bartelt et al3 found that severe glenoid lucency or component loosening occurred in 29.4% at 6.6 years.

Denard et al9 treated a cohort of young patient with cemented keeled glenoid and found a survival rate of only 62.5% at 10 years.

Alternative treatments available in this patient population include the use of humeral head resurfacing arthroplasty, which has the advantage of preserving humeral bone stock.

However, recent study in the Australian Registry shows increased risk of revision at 2 years.15

On the glenoid side, use of glenoid resurfacing with or without biologic tissue augmentation may have a potential in offering patients long-term pain relief while preserving the option of TSA later in life.

In this chapter, the authors describe the surgical techniques in performing shoulder HA as well as glenoid resurfacing with or without the use of biologic tissue augmentation.

Preoperative Planning

The key consideration for planning a shoulder arthroplasty is the evaluation of the bony structures and the associated soft tissue component.

If there are clinical or radiographic evidence such as chronic instability or cuff failure, consideration must be given for a constrained prosthesis such as reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

If patient had a prior Putti-Platt procedure, one can expect a shortened subscapularis tendon. At this time, the approach for subscapularis take down should be either osteotomy or Z-lengthening.

If patient had a prior Magnuson-Stack procedure, one should consider starting the osteotomy more laterally to reposition the subscapularis tendon more anatomically.

If there is significant glenoid bone wear, corrective strategies with high side reaming or bone grafting procedures may be used. In cases of severe wear and humeral head subluxation, Walch et al27 suggested that patients would do better with a reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

If the glenoid bone loss is central, then one can also plan for autograft versus allograft use.

If there is concern for infection, preoperative workup including complete blood count, chemistry panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein markers should be obtained. Preoperative joint aspiration and intraoperative

biopsies for culture can be routinely done to rule a subtle infection. If there is a concern for infection, glenoid resurfacing with biologic tissue interposition should not be performed.

Positioning

Patient is placed in the beach-chair position with arm hanging at the side.

The body is supported by a beanbag. The shoulder blade is supported in the back via folding over the posterosuperior corner of the beanbag or using additional towels for support.

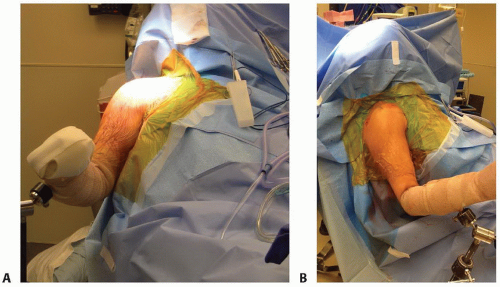

The operated shoulder is widely draped to include the coracoid. Iodine-impregnated drapes are used to cover over the operative field to minimize risk of bacterial contamination (FIG 1A,B).

The arm is prepped and placed in an arm holder with elbow gently bent at 90 degrees and arm abducted approximately 20 degrees.

The bony landmarks, including clavicle, coracoid, and anterior acromion are identified and marked.

The incision is marked out with approximately 15 cm in length and centered over the coracoid, extending over the humeral insertion of the pectoralis major tendon.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Humeral Exposure

A long deltopectoral approach is performed. The cephalic vein is mobilized medially.

The biceps tendon is identified in the intertubercular groove and released from the supraglenoid tubercle for later tenodesis.

The top 1 cm of the pectoralis tendon is released from the humeral shaft.

The three borders of the subscapularis (superior, lateral, and inferior) are identified, and the subscapularis is detached in one of three ways: fleck osteotomy, tenotomy, or peeled off from the bone.

The subscapularis is tagged and released in continuity with the underlying capsule from the humeral neck and then mobilized on its superior, posterior, and inferior surfaces.

Resection of the anteroinferior capsule is not routinely performed but would be considered in case of limited external rotation.

The capsulectomy would help with both increased excursion of the subscapularis and improved glenohumeral range of motion.

The anterior circumflex vessels are identified and ligated with metallic clips.

At this time, the arm is externally rotated, and a periosteal elevator is placed over the medial neck to retract the soft tissue and expose the inferior humeral neck.

The arm is progressively externally rotated as the inferior humeral capsule is released from the inferior and posterior neck.

The latissimus dorsi tendon is now visible over the medial shaft and is also released for enhancing the exposure.

Now, the arm can be fully externally rotated and extended to expose the entire humeral head.

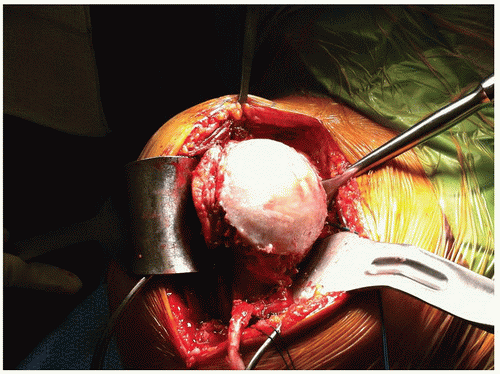

Four retractors are now placed to fully expose the head: Bennett retractor placed over the medial neck, Chandler retractor is placed intra-articularly to distract the head, a deltoid retractor is placed laterally to protract the humerus, and a small Hohmann retractor over the head to expose the posterior rotator cuff (TECH FIG 1).

▪ Humeral Hemiarthroplasty

The “ring” of osteophytes is now removed from the humeral head with rongeurs for ease of identifying the true humeral neck.

Then, the humeral osteotomy is performed along the true anatomic neck (TECH FIG 2A).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree