Hemiarthroplasty for Proximal Humerus Fractures

Kamal I. Bohsali

Michael A. Wirth

Steven B. Lippitt

ANATOMY

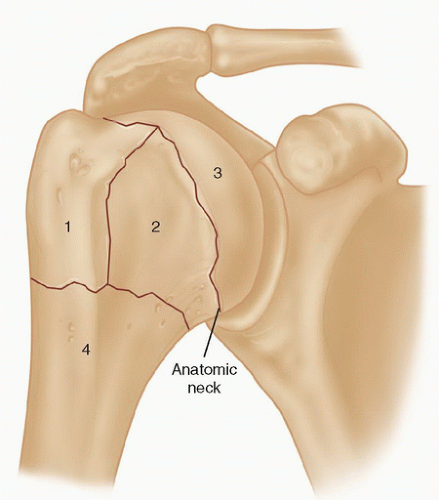

The proximal humerus consists of four segments: the greater tuberosity, lesser tuberosity, articular segment, and humeral shaft (FIG 1).

The most cephalad surface of the articular segment is, on average, 8 mm above the greater tuberosity.18 Humeral version averages 29.8 degrees (range, 10 to 55 degrees).18,23

The intertubercular groove lies between the tuberosities and forms the passageway for the long head of the biceps as it traverses from the intra-articular origin into the distal arm.

The tuberosities attach to the articular segment at the anatomic neck. The greater tuberosity has three facets for the corresponding insertions of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor tendons; the lesser tuberosity has a single facet for the subscapularis.

The deltoid, pectoralis major, and latissimus dorsi all insert on the humerus distal to the surgical neck. These soft tissue attachments contribute to the deforming forces sustained with proximal humerus fractures.

FIG 1 • Neer classification of proximal humerus fractures: 1, greater tuberosity; 2, lesser tuberosity; 3, articular surface; 4, shaft.

The humeral head receives its blood supply from the anterolateral branch of the anterior humeral circumflex artery (the arcuate artery of Laing) and the posterior humeral circumflex artery. The artery of Laing courses parallel to the lateral aspect of the long head of the biceps and enters the humeral head at the interface between the intertubercular groove and the greater tuberosity.20 More recent studies have indicated that the posterior branch may play a larger role in perfusion of the fractured humeral head, reducing the risk of osteonecrosis.10,15,16

PATHOGENESIS

The incidence of proximal humerus fractures is increasing with an aging population and associated osteoporosis.

The mechanism of injury may be indirect or direct and secondary to high-energy collisions in younger patients (eg, motor vehicle accidents, athletic injuries) or falls from standing height in elderly patients.

Pathologic fractures from primary or metastatic disease should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Risk factors for the development of proximal humerus fractures in the elderly patient population include low bone density, lack of hormone replacement therapy, previous fracture history, three or more chronic illnesses, and smoking.17

NATURAL HISTORY

Neer’s classic study in 1970 compared the results of nonoperative treatment with hemiarthroplasty for three- and four-part displaced proximal humerus fractures. No satisfactory results were found in the nonoperative group owing to inadequate reduction, nonunion, malunion, and humeral head osteonecrosis with collapse.22

Stableforth28 reaffirmed this in a study in which patients were randomized to nonoperative management or prosthetic replacement. The patients with displaced fractures treated nonoperatively had worse overall results for pain, range of motion, and activities of daily living.

Olerud et al25 most recently demonstrated significantly improved quality of life with a trend toward pain scores with four-part fractures treated with hemiarthroplasty versus observation.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history and complete physical examination should be performed. History should include mechanism of injury, premorbid level of function, occupation, hand dominance, history of malignancy, and ability to participate in a structured rehabilitation program.14

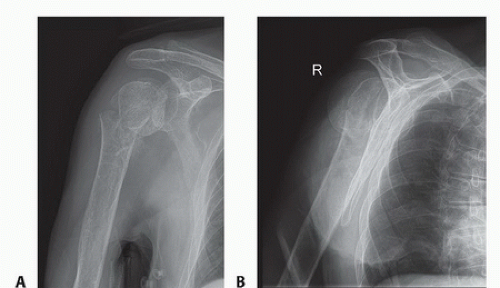

FIG 2 • A. Anteroposterior (AP) and (B) scapular “Y” views of a displaced four-part proximal humerus fracture without evidence of concomitant dislocation. (Copyright Kamal I. Bohsali, MD.)

A review of systems should involve queries regarding loss of consciousness, paresthesias, and ipsilateral elbow or wrist pain.

On physical examination, the orthopaedic surgeon should look for swelling, soft tissue injuries, ecchymosis, and deformity. Posterior fracture-dislocations will demonstrate flattening of the anterior aspect of the shoulder with an associated posterior prominence. Anterior fracture-dislocations present with opposite findings.14

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Appropriate radiographs include biplanar views of the shoulder14 (FIG 2). If the axillary view cannot be obtained because of patient discomfort, alternate views such as the Velpeau trauma axillary view can be used to evaluate and classify the glenohumeral articulation.2

The Neer classification is based on the four anatomic segments of the proximal humerus: the humeral head, the greater and lesser tuberosities, and the humeral shaft (see FIG 1).11 Number of parts is based on 45 degrees of angulation or 1 cm of displacement from neighboring segments.

The AO/ASIF/OTA Comprehensive Long Bone Classification system distinguishes the valgus impacted four-part proximal humerus fracture from other four-part fractures with partial preservation of the vascular in-flow to the articular segment through an intact medial capsule.8,19,26

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Acute hemorrhagic bursitis

Traumatic rotator cuff tear

Simple dislocation

Acromioclavicular separation

Calcific tendinitis2

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative treatment usually is reserved for minimally displaced fractures of the proximal humerus, which account for nearly 80% of these injuries.

The characteristics of the fracture (ie, bone quality, fracture orientation, concurrent soft tissue injuries), the personality of the patient (eg, compliant, realistic expectations, mental status), and surgeon experience all affect the decision to proceed with operative intervention.

Moribund individuals and patients unable to cooperate with a postoperative rehabilitation program (eg, closed head injury) are not appropriate candidates for operative intervention.

In general, nonoperative management of complex, displaced proximal humerus fractures has not proven as successful.

Initial immobilization with a sling and axillary pad may be helpful. Gentle range-of-motion exercises may be started by 7 to 10 days after the fracture event when pain has decreased and the patient is less apprehensive.2

Intermittent biplanar radiographs are essential to determine additional displacement and the interval stage of healing.2

Active and active-assisted range-of-motion exercises are initiated with evidence of radiographic union. Inform the patient that he or she may never attain symmetric range of motion or strength when comparing the affected versus the uninjured side.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The goal of surgery is to anatomically reconstruct the glenohumeral joint with restoration of humeral height, replication of appropriate prosthetic retroversion, and establishment of secure tuberosity fixation.

Prosthetic replacement is the preferred treatment of most four-part fractures, three-part fractures and dislocations in elderly patients with osteoporotic bone, head-splitting articular segment fractures, and chronic anterior or posterior humeral head dislocations with more than 40% of the articular surface involvement.1,2,23

Several studies have indicated that the outcome of primary hemiarthroplasty for acute proximal humerus fractures is superior to that from late reconstruction.6,24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree