Hemiarthroplasty and Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty for Glenohumeral Arthritis with an Irreparable Rotator Cuff

Scott P. Stephens

Steven B. Lippitt

Ryan T. Bicknell

Michael A. Wirth

DEFINITION

Glenohumeral arthritis represents the loss of articular cartilage and joint space, often with associated osteophyte and cyst formation, bone erosion, and soft tissue contractures.

It can result from degeneration, inflammatory pathology, trauma, cuff deficiency, or can be multifactorial and is associated with loss of function and pain in varying degrees that can dramatically affect a patient’s quality of life.

Rotator cuff tendon tears have increased prevalence with age and can occur independently or as a result of the disease process causing glenohumeral degeneration. The arthritic etiology though can help provide insight into the rotator cuff integrity.

Rotator cuff tear arthropathy (RCTA) describes the unique progression of glenohumeral arthritis that occurs in patients who have sustained massive rotator cuff tendon tears and involves cephalic migration of the humerus with characteristic degenerative changes.10

Although irreparable rotator cuff tears are classically associated with RCTA, they can also be seen with rheumatoid as well as osteoarthritis, although the degree and quality of tendon involvement may vary.

Surgical treatment originally included the use of total shoulder arthroplasty, but due to the high rate of glenoid loosening from abnormal contact loading, hemiarthroplasty later became the preferred surgical option.1,5,6,11

The development of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) has expanded prosthetic options for this condition and offered surgeons the ability to address patients who have continued glenoid degenerative progression as well as loss of rotator cuff function.2,4

The key aspects in managing this condition are recognizing this unique form of glenohumeral arthritis and understanding the pathophysiology that results in poor outcomes with the use of conventional total shoulder replacement.

It is also essential to determine patient’s physiologic age and activity levels, as well as understanding the patient’s goals for surgical intervention which can include improving function, pain, stability, or a combination of these.

ANATOMY

The glenohumeral joint relies on a combination of static stabilizers, including negative intra-articular pressure, articular surface geometry, labrum, capsular ligaments, and dynamic stabilizers, including the rotator cuff muscles, deltoid, pectoralis major, and latissimus dorsi.3,7,9,13

The rotator cuff is a convergence of tendons consisting of the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor that attach just lateral to the articular surface on the humeral tuberosities.

Although many static as well as dynamic stabilizers affect shoulder stability, the rotator cuff muscles play an important role in centering and stabilizing the humeral head within the glenoid concavity throughout a range of motion by force couple balancing. The loss of these tendons diminishes the ability of the humerus to be compressed into the glenoid, leading to a loss of the ball-and-socket mechanism of the glenohumeral joint and is a key step in progression of rotator cuff arthropathy.

Even without cephalic migration of the humerus, the loss of these structures can compromise the longevity of conventional shoulder arthroplasty, and their contribution to both worsening function and pain must be determined.

The deltoid muscle originates from the lateral clavicle, acromion, and scapular spine and inserts on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus and is innervated by the axillary nerve. It is the primary means for arm elevation, particularly following rotator cuff dysfunction.

The bony anatomy surrounding the glenohumeral joint is especially critical with the loss of soft tissue restraints, particularly the coracoacromial arch which comprises the coracoid, acromion, and coracoacromial ligaments.

The loss of concavity compression provided by the rotator cuff places greater emphasis on these structures. The active pull of the deltoid can progressively advance the humeral head upward toward the acromion and eventually without the static restraint of the coracoacromial ligament, results in progressive displacement between the coracoid and acromion.14

PATHOGENESIS

The term rotator cuff tear arthropathy was first popularized by Dr. Neer in the early 1980s, describing a constellation of symptoms, including rotator cuff insufficiency, superior migration of the humeral head, advanced glenohumeral arthritis, and potential bony architectural changes including acetabularization of the acromion and alterations in the proximal humerus.10

Rotator cuff tear etiology can result from progressive degeneration, trauma, or be multifactorial but regardless of the cause, a chronic retracted tear involving multiple tendons is the initial step to progression of this pathology.

Although the loss of multiple rotator cuff tendons is necessary for development of RCTA, not all patients with cuff tears progress to arthritis.

A variety of theories have been proposed to explain why only some patients progress to arthritis after loss of rotator cuff function. Theories include a loss of nourishment from escaped synovial fluid, deterioration of cartilage cells from disuse, abnormal physical stresses, and accumulation of either calcium phosphate crystals or cartilage debris. However, the exact etiology is still unknown and likely involves biologic as well as mechanical factors.3

The loss of stabilization results in superior migration of the humeral head from the active pull of the deltoid until mechanical abrasion occurs with the undersurface of the acromion and eccentric loading on the superior rim of the glenoid.

In the same instance, this migration reduces tension on the deltoid and alters its moment arm, diminishing its effectiveness for arm elevation.

Therefore, the intact coracoacromial arch becomes the primary superior stabilizer to the uncovered humeral head.

The coracoacromial arch though can be compromised by progressive abrasion with the uncovered humeral head or during surgery by section of the coracoacromial ligament during acromioplasty.

Compromise of the coracoacromial arch coupled with a substantial rotator cuff defect permits anterosuperior instability of the humeral head with deltoid contraction.

This anterosuperior instability, or escape, eliminates the fulcrum needed for the deltoid to elevate the arm and leads to a loss of the ball-and-socket mechanism of the glenohumeral joint.

The loss of the ball-and-socket mechanism from loss of rotator cuff muscles and inability of a functioning deltoid to elevate the arm is known as pseudoparalysis and is evident by lack of active glenohumeral elevation past 90 degrees with maintained passive elevation.

NATURAL HISTORY

Rotator cuff tendon tears can result from multiple etiologies but studies following conservative treatment have noted progressive increase in size of the tear, atrophy of muscles, and pain with associated decrease in function.14,16

Patients with glenohumeral degeneration from osteoarthritis, avascular necrosis, or inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis will typically have an intact rotator cuff, although potentially thinned. These patients lose function primarily from the pain associated with degenerative changes, and the rotator cuff can actually be protected from the resulting decrease in activities of the affected arm.

For patients who have sustained irreparable rotator cuff tears and have developed glenohumeral arthritis (ie, RCTA), the integrity of the rotator cuff, the articular cartilage, and the coracoacromial arch all characteristically degenerate in a progressive manner.

Few studies have attempted to follow patients during conservative management of RCTA, but progression has been noted of increasing tear size, fatty infiltration, cephalic migration, and glenohumeral arthritis.

As the disease progresses, patients can experience superior glenoid bone erosion, as well as anteriorly, depending on the integrity of the coracoacromial arch. The cephalic migration may also result in erosion of the acromion that may become problematic when tension is increased in the deltoid after placement of a reverse shoulder replacement and result in acromion fracture.

This progression of migration and worsening degeneration can result in increased pain, stiffness, diminishing function, and potentially anterosuperior instability.

PATIENT’S HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients can report either an acute event that resulted in deterioration or from a chronically progressive decline in function and pain (“tear” vs. “wear”).

These patients can experience loss of range of motion either from functional limitations seen with rotator cuff deficiency or from bone erosions that alter the kinematics and stability of the shoulder.

Physical examination typically demonstrates pain with range of motion, as well as crepitus, often between the humeral head and the acromion.

Due to loss of rotator cuff integrity, these patients can have a large subacromial effusion from synovial fluid escape.

Examination should include a careful evaluation of the rotator cuff:

Supraspinatus function can be evaluated by the inability to abduct the arm from the side as well as a positive drop arm test.

Subscapularis function can be evaluated by loss of internal rotation strength with a positive lift-off test, belly press sign, or bear hug test, which may affect implant choice due to anterior stability concerns.

Infraspinatus and teres minor function can be evaluated by loss of external rotation in adduction (infraspinatus) as well as abduction (teres minor), with a positive external rotation lag sign (infraspinatus) and hornblower’s test (teres minor). It is important to rule out dysfunction of these muscles, which may compromise results and necessitate soft tissue transfers during the procedure to maximize patient’s ability to reach their hand to their head.

It is also important to evaluate deltoid function, specifically for patients with a history of dislocation, trauma, or previous surgeries who may have sustained an injury to the axillary nerve. This may necessitate further nerve function studies to document integrity. Deficient axillary nerve functioning will significantly affect a patient’s outcome and requires determination prior to placing a reverse shoulder prosthesis.

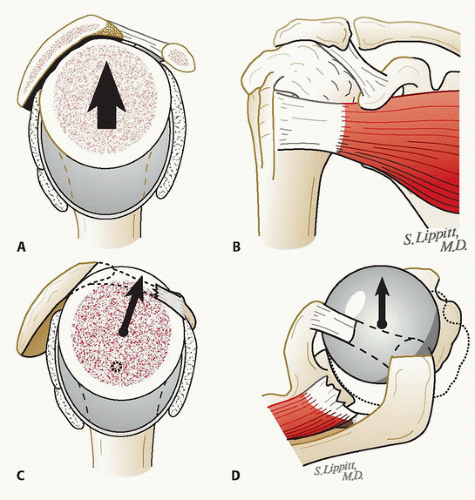

Patients can also suffer from instability from loss of dynamic restraint, and the direction should be evaluated. By having the patient contract their deltoid with the arm in an adducted position, the proximal migration and impaction into the acromion can be noted (FIG 1A,B).

If the coracoacromial arch is incompetent, then during deltoid contraction the proximal humerus can be delivered subcutaneously between the acromion and coracoid. This is described as anterosuperior escape of the humeral head (FIG 1C,D).

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs in two planes should be the initial diagnostic test. These should include an anteroposterior (AP) view in the plane of the scapula and an axillary view. Other views that may be helpful include an AP view of the shoulder, true AP of the glenohumeral joint with the humerus in internal and external rotation, and a scapular Y view.

The plain films can denote the typical features that are involved in all arthritic processes such as loss of joint space, osteophyte formation, cysts as well as bone loss.

Additionally, radiographs can provide clues to the etiology such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, avascular necrosis, prior proximal humeral fracture, or RCTA.

RCTA can be identified by characteristic radiograph findings.

AP plain radiographs

Decreased acromiohumeral distance, typically less than 6 mm

Superior and possibly anterior glenoid wear

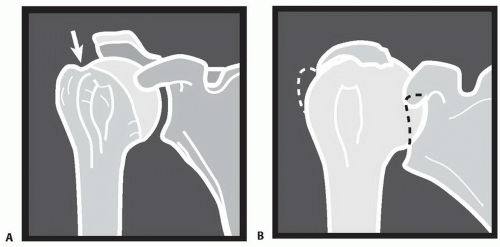

Erosion of the acromion resulting in an “ acetabularized” appearance (FIG 2A,B)

“Femoralization” of the proximal humerus (ie, rounding off of the tuberosities)

Axillary radiographs

Direction and degree of humeral instability

Medial glenoid erosion and available bone stock for glenoid implant fixation

Glenoid version and anterior/posterior glenoid wear

Computed tomography (CT) scan can evaluate the following:

Bony architecture of humerus, glenoid, and acromion

Glenoid bone stock

Alterations in glenoid version and glenohumeral congruency

Hardware from prior rotator cuff repairs

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can assess the following:

Integrity of soft tissue and rotator cuff tendons, especially in patients with inflammatory arthritis

Rotator cuff retraction and fatty infiltration of the muscle belly which may prognosticate an irreparable tendon

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Septic arthritis

Osteoarthritis

Inflammatory arthropathy

Neuropathic (Charcot) arthropathy

Crystalline arthropathy

Suprascapular nerve entrapment

Cervical pathology

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The combination of an irreparable rotator cuff and glenohumeral arthritis typically results from a chronic process and nonoperative modalities may be attempted to alleviate pain and improve function. This may be the treatment of choice depending on the patient’s overall physiologic health.

These modalities consist of the use of anti-inflammatory medications, cortisone injections, and physical therapy.

Physical therapy should focus on painless range of motion and not cause more inflammation and pain, which may create further loss of function. Protocols should focus on strengthening of the deltoid, any remaining rotator cuff, as well as periscapular muscles to help compensate for impaired cuff function.

Cortisone injections should be limited though in cases where surgical intervention may be inevitable, as this can cause further insult to remaining cuff as well as increase the risk of infection.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

The type of surgical intervention should include consideration of the patient’s age, preexisting medical conditions, pain, functional level, activities of daily living as well as the patient’s compliance and expectations.

Physical examination, paying special attention to rotator cuff integrity and stability as well as arthritic etiology is instrumental in determining the type of the prosthesis that can maximize a patient’s outcome (Table 1).

Preoperative radiographs and CT scans should be reviewed to determine the quality of glenoid bone stock, glenoid version, and deformity and determine if bone grafting may be necessary.

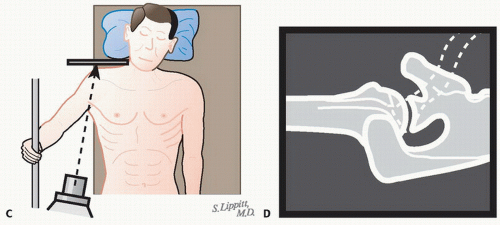

Radiographs can also identify any potential deformities that may prevent passage of the humeral stem. The AP radiograph allows templating to estimate the size and fit of the humeral components (FIG 3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree