General Considerations, Indications, and Outcomes

Victor M. Goldberg

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of joint disease and is the second leading cause of disability in persons older than 50 years. It affects to some degree almost 90% of persons older than 65 years. Health care expenses for treatment of arthritis and other related chronic joint disorders in the United States are estimated at over $116 billion annually. In 2003, approximately 418,000 total knee replacements and over 220,000 hip replacements were performed in the U.S., and this number appears to be increasing at the rate of 11% for knee replacement and 2.5% for hip replacement per year. Although it can cause significant pain and loss of function over time, the treatment is usually nonoperative for the most part and consists of rest, physical therapy, analgesics, anti-inflammatory medication, and modifications of daily activities. For those patients who have significant pain and functional disability despite conservative treatment, carefully selected surgical procedures may provide substantial benefits.1 Long-term studies evaluating the functional outcome of total joint replacement have demonstrated predictable and consistently satisfactory outcomes even in younger and more active patients.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 These results provide the basis for an appealing therapeutic alternative for the patient suffering from the problems of OA. However, the beneficial results that can be seen after total joint replacement must be tempered by the possibility of failure secondary to mechanical and biologic problems. The end results of these complications may be less than optimal function, sometimes in a relatively young and active individual. Because of these possibilities, other surgical procedures should be considered that may improve the patient’s symptoms and retard the progression of the disease. It is important to understand the indications and outcomes of other procedures that preserve the diarthrodial joint, such as osteotomy and joint débridement, to establish a complete treatment program for the patient with OA. This chapter provides the reader with an overview of the indications and expectations for the general types of surgical procedures that are presently available. Each anatomic area is discussed in detail in the sections that follow.

General Considerations

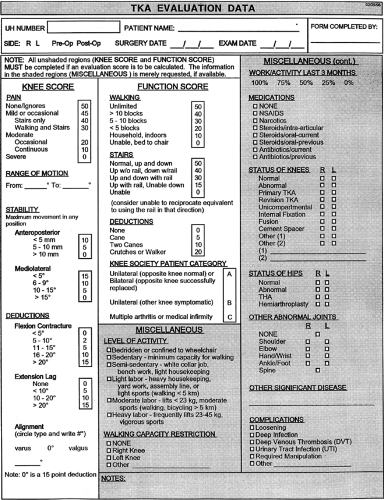

Before considering surgical treatment, the physician must weigh the risks and benefits of each procedure. This is especially important today, with the larger number of younger, active patients who are developing secondary arthritis after trauma or sports-related injuries. Although there are no absolute indications or contraindications for any surgical procedure, certain general concepts are important. For each individual patient, the physician should endeavor to develop a quantitative assessment of parameters of function to determine the appropriate therapeutic program. Not only is this an aid in the selection of the best therapeutic strategy, but it can also be of help in prospective studies evaluating the outcome of different surgical procedures. Figure 19-1 summarizes the scoring system for the evaluation of the knee as adapted by the Knee Society.

Similar scoring systems have been developed for the hip and other joints.

Similar scoring systems have been developed for the hip and other joints.

Pain is a key factor in the decision process. Rest pain, if it is present, poses a major problem for the patient and usually requires narcotics for control. Greater consideration for surgical intervention should be given in this circumstance. Activity-related discomfort is also important and may affect the patient’s quality of life. However, many times these symptoms may be treated by nonoperative modalities, although lesser surgical procedures than total joint

reconstruction may be of greater use during this stage of the disease.

reconstruction may be of greater use during this stage of the disease.

Functional considerations are also central in the therapeutic decision process. Walking distance usually correlates with the anatomic severity of the joint disease. The need for external supports (e.g., canes) is an objective indication of the functional impairment experienced by the patient. The activities of daily living are also important. The ability to climb stairs and get into and out of an automobile or chair should be quantified. The physician should inquire about loss of time from work and the capability to perform household chores as well as recreational activities. This information gives the physician an estimate of the patient’s quality of life and the socioeconomic problems the person may be experiencing. Many patients seek medical care because of the loss of their ability to participate in recreational sports such as golf or tennis. This also must be considered when developing a treatment plan.

Anatomic considerations include the range of joint motion, the presence or absence of extremity deformity, and an estimation of joint stability. This last function is easier to evaluate in the knee joint than in other joints. For example, in considering the hip, ligaments cannot be examined, and indirect techniques (e.g., evaluation of pain and deformity) may indicate joint integrity. The degree of motion or the extent of deformity is important not only in defining the stage of the disease but also in influencing the choice of the surgical procedure as described in subsequent chapters. The recent description of hip problems associated with femoral neck impingement on the anterior acetabular rim as a potential cause of secondary OA may, if recognized early in the natural history of hip disease, provide the indications for early intervention using arthroscopic techniques. Contouring the femoral neck as well as debriding any associated tears of the labrum may prevent further significant hip disease with the need for later joint arthroplasty.10,11

There have been a number of recent studies addressing the validity of several quantitative outcome assessments in hip and knee arthroplasty. Scoring systems that report categorical outcomes rather than numeric systems are less reliable in defining the hip or knee score. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that patients with a poorer preoperative status may not have as good an outcome as those with a higher level of preoperative function.12 The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), SF-36, and Oxford Twelve Item Knee Questionnaires have all been demonstrated to be valid systems to assess outcome measures. Studies have pointed to the WOMAC and SF-36 as better measures of pain and function and therefore are more reflective of patient-oriented outcomes than physician assessments.12,13,14

These data must be integrated into an overall evaluation of the present state of the patient’s joint disease. Additional important considerations are the age and weight of the individual. For example, total joint arthroplasty has a higher chance of mechanical failure in a young, overweight, active individual, and other surgical procedures (e.g., arthrodesis) should be considered. By contrast, an elderly patient who may not have severe anatomic abnormalities but whose activities have had to be significantly modified because of pain may be a much better candidate for total joint replacement.

The ability of the patient to cooperate in any treatment plan is also important in surgical selection. Certain procedures (e.g., joint débridement or arthroplasty) require greater cooperation of the patient during the postoperative rehabilitation period compared with arthrodesis. In addition, the patient’s knowledge of the disease and the possible outcomes of the surgical procedure must be understood. The patient’s perception of what he or she hopes to obtain as a result of the surgery is central in the decision process. All too frequently, the physician does not ask the patient about his or her expectations. Although each person must be considered individually, information relative to the reported outcome of each surgical procedure is important in educating that individual. In some circumstances, an individual may desire a curative procedure, which may be unrealistic. At other times, cosmetic correction is foremost in the patient’s mind. However, the patient may have become well adjusted to the malposition of the extremity, and if function is not compromised and the deformity does not constitute an anatomic threat to other joints, the mere presence of malposition may not be a reason for surgery. Specific quantitative assessment of the outcome of operative or nonoperative treatment will become more important in the future as the availability of health resources may become compromised.15

Long-term bed-bound or wheelchair-confined patients may desire a return to a community ambulatory status, but extra-articular anatomic factors may reduce the chance of a successful outcome. However, the improvement of function to an effective, household ambulatory status may be an attainable goal. These outcomes must be understood clearly by the patient and the physician.

The general health of the patient must be considered in evaluating surgical risk factors. Cardiovascular or respiratory disease may be severe enough to be a contraindication to general anesthesia and a major surgical procedure. However, regional or spinal anesthesia can often be substituted, thereby reducing the risk. One study assessing the results of randomized trials comparing epidural or spinal anesthesia to general anesthesia suggested that patient receiving regional anesthesia had a reduced rate of mortality and complications.16,17 Many of the patients who are candidates for reconstructive surgery in the treatment of OA are elderly and are poor surgical and anesthetic risks. However, chronologic age alone should not be considered a contraindication; rather, the physiologic age of each patient must be considered in determining the risk/benefit ratio. It is important, however, to recognize, stabilize, and correct medical conditions that may exist before surgery. Some of the more common conditions include chronic obstructive lung disease, hypertension, angina pectoris, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, and diabetes mellitus. Any factors that predispose to infection (e.g., immunosuppressive drugs) should be considered and modified before surgery.

In addition to the risk/benefit ratio of any treatment, the cost/benefit relationships of a procedure must also be considered. Will the surgery enable the patient to become more self-sufficient or allow the individual to remain independent? If the surgical procedure is successful, can the person continue working or return to employment? The answers to these questions must be considered in the overall decision-making process. Care must be taken not to allow the decision to operate to depend heavily on socioeconomic considerations because many times surgery will reduce the dependence of the patient on a caregiver, which may be difficult to quantify.

There are no absolute indications for surgical intervention in OA. Many factors must be considered, and no one treatment algorithm is appropriate for any surgical treatment. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) has published care paths for the treatment of OA of the knee; however, within the pathway, flexibility is appropriate to treat individual patients.18 Similarly, there are no absolute contraindications to surgery in patients with OA, although relative contraindications do exist. Active infection, overwhelmingly poor medical health, and inadequate anatomic structures (e.g., motor control) or available bone stock are reasons to reject surgical treatment. Other factors may increase the chances for a poorer outcome when a specific operative procedure is considered. For example, patients who are morbidly obese or whose joint in question is neuropathic usually do poorly when arthroplasties are performed, and suitable alternatives should be substituted, if possible.

More knowledge is being accumulated about the outcome of many operative procedures and which risk factors are most important in determining their long-term results; but clearly, the decision of which surgical procedure to use, when to use it, and on whom to use it must still be left to sound clinical judgment. Most important, each patient is an individual, and the positive and negative aspects of the treatment must be carefully considered for that patient. Finally, the availability of a large body of information on the internet has made patients more knowledgeable about their treatment alternatives. This does present a new challenge for physicians caring for these patients, as much of the data on this media has not been validated.

Types of Surgical Procedures

The surgical treatment modalities presently used for patients with OA may be classified into four broad categories: osteotomy, débridement, arthrodesis (fusion), and arthroplasty. General principles have evolved for each procedure that are applicable to its use in any OA joint problem. Table 19-1 provides the reader a comparison of surgical alternatives in OA detailing the indications and expected outcomes for each surgical category. The recent introduction of minimally invasive procedures for hip and knee arthroplasty has accelerated the postoperative rehabilitation and return of function. However, longer term studies to date have not demonstrated any ultimate advantage for this new approach.19,20

Osteotomy

One of the advantages of an osteotomy is that it addresses both biologic and mechanical problems without sacrificing the integrity of the joint. The two main goals of this procedure are to relieve pain and to prevent the progression of OA. If joint malalignment is present (e.g., genu varum of the knee), with resultant abnormal force distribution, an osteotomy to realign the joint in a more normal configuration will correct the abnormal mechanical loads causing progression of the disease. The aim of the procedure is to redistribute the forces in such a way that healthy cartilages on the relatively uninvolved side of the joint will be brought into apposition with each other. In addition, there is evidence that osteotomizing the bone changes the pattern of vascular supply to the joint, which may have a biologic effect on the OA process.21

Osteotomy was one of the earliest procedures to be used in the surgical management of OA. Although osteotomy is not curative, when patients are carefully selected, excellent pain relief, improved function, and maintenance of physiologic joint motion and stability may be expected.22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 It is especially applicable for the young, active individual when relatively normal articular cartilage is present. A functional range of motion must be present before surgery, because some motion may be lost after surgery. The knee joint, for example, should have close to 90° of flexion without a fixed flexion contracture of greater than 20° for osteotomy to be considered. If a deformity (e.g., genu valgum) is present, it should not be so excessive that correction to anatomic alignment cannot be obtained. Additional important considerations include satisfactory periarticular muscle control of the joint and intrinsic joint stability. Considerable cooperation of the patient and understanding are necessary for a successful outcome. The development of sophisticated instrumentation has provided the basis for improved surgical technique with the expectation of improved outcomes.30,36 Further, the use of internal fixation devices lessens the postoperative need for casts and enables maintenance of joint motion. There have been reports of the combined use of osteotomy and débridement of the knee joint, with encouraging early results in difficult, more advanced problems of OA of the knee.37,38 The application of specific additional biological procedures to encourage formation of new cartilage, such as microfracture, may improve the longer term outcome for knee osteotomy. This may delay the need for total knee replacement in younger patients. Osteotomy of the hip has enjoyed a resurgence lately with the recognition of subtle anatomical abnormalities in younger patients with very early OA. The periacetabular osteotomy described by Ganz has been reported to result in significant improvement in pain and function with a satisfactory rating of 90%.11

Débridement

The concept of smoothing irregular joint surfaces and removing the loose bodies and inflamed synovium that add to the destructive processes in OA of the knee was popularized by Magnuson39 in 1946. In appropriate

circumstances, the hip, ankle, wrist, and elbow may also benefit from this surgical modality.40,41,42 For this procedure to be considered, joint malalignment either should not be present or should be correctable with an osteotomy. A functional range of motion is necessary. It is also helpful to have preservation of at least 50% of the articular cartilage surface. The results are variable and depend a great deal on the careful selection of a motivated patient.40 Pain relief can be impressive, but many times some joint mobility is lost after surgery. Insall43 reported about 75% good results after knee joint débridement, with an average of 6.5 years of follow-up. A joint effusion is frequently present for a prolonged period after surgery, but this gradually subsides. Maximal improvement is usually not seen before 12 months after surgery. The addition of continuous passive motion in the postoperative rehabilitation phase may improve the results of débridement.44 Advances in arthroscopic techniques, with their decrease in morbidity and postoperative recovery time, make débridement a more attractive approach in patients who present with early OA, and reports indicate an optimistic outcome in carefully selected patients.38,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50 However, one recent Veteran’s Administration study reporting the results of a randomized trial comparing arthroscopic lavage, débridement, or sham procedures in 180 patients demonstrated at a 2-year follow-up no statistical differences. There were a number of issues in this study that detracted from the conclusions including a 44% dropout rate, only male patients, and nonspecific indications for surgical intervention.51 By contrast, Aaron reported a study of 122 consecutive patients who had failed conservative treatment and underwent arthroscopic débridement of the knee. At 34 months follow-up, 90% of the patients with objective mild arthritis demonstrated marked improvement by 6 months after surgery. However, there was little improvement in those patients with high grade OA according to clinical and radiographic signs.52 Specific débridement techniques such as microfracture when used for local cartilage defects may be very effective in preserving joint function.50 The use of débridement and newer biological treatments may prolong the patient’s clinical course without the need for total joint replacement (see Chapter 23).

circumstances, the hip, ankle, wrist, and elbow may also benefit from this surgical modality.40,41,42 For this procedure to be considered, joint malalignment either should not be present or should be correctable with an osteotomy. A functional range of motion is necessary. It is also helpful to have preservation of at least 50% of the articular cartilage surface. The results are variable and depend a great deal on the careful selection of a motivated patient.40 Pain relief can be impressive, but many times some joint mobility is lost after surgery. Insall43 reported about 75% good results after knee joint débridement, with an average of 6.5 years of follow-up. A joint effusion is frequently present for a prolonged period after surgery, but this gradually subsides. Maximal improvement is usually not seen before 12 months after surgery. The addition of continuous passive motion in the postoperative rehabilitation phase may improve the results of débridement.44 Advances in arthroscopic techniques, with their decrease in morbidity and postoperative recovery time, make débridement a more attractive approach in patients who present with early OA, and reports indicate an optimistic outcome in carefully selected patients.38,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50 However, one recent Veteran’s Administration study reporting the results of a randomized trial comparing arthroscopic lavage, débridement, or sham procedures in 180 patients demonstrated at a 2-year follow-up no statistical differences. There were a number of issues in this study that detracted from the conclusions including a 44% dropout rate, only male patients, and nonspecific indications for surgical intervention.51 By contrast, Aaron reported a study of 122 consecutive patients who had failed conservative treatment and underwent arthroscopic débridement of the knee. At 34 months follow-up, 90% of the patients with objective mild arthritis demonstrated marked improvement by 6 months after surgery. However, there was little improvement in those patients with high grade OA according to clinical and radiographic signs.52 Specific débridement techniques such as microfracture when used for local cartilage defects may be very effective in preserving joint function.50 The use of débridement and newer biological treatments may prolong the patient’s clinical course without the need for total joint replacement (see Chapter 23).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree