Future Therapeutic Options

Paul D. Miller

Current osteoporosis therapies have been shown to reduce the risk of fragility fractures generally from 50% to 65% over a period of 3 years. No pharmacological intervention for any disease abolishes risk, but future therapeutic options for the treatment of osteoporosis are being designed with the hope of improving on the risk reduction that can be currently achieved.

However, there are additional considerations in designing future choices for the pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis besides improved efficacy: improved safety profiles and fewer side effects, better formulations that might encourage adherence and persistence, and therapies that might increase bone strength through different mechanisms of action other than just by bone mineral density and reducing bone turnover [1,2,3,4,5]. The osteoporosis-specific pharmacological agents that are potential future therapeutic options are listed in Table 11.1.

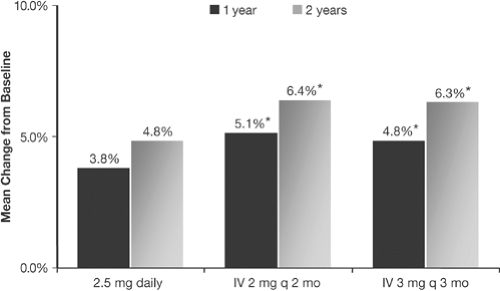

Very recently, intravenous ibandronate (3 mg intravenous injection every 3 months) was registered for postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO) (Fig. 11.1) [6]. The approval for intravenous ibandronate was made in the same manner that weekly or monthly bisphosphonate formulations were Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved on the basis of noninferiority comparative studies. Noninferiority studies compare the effects of the fracture-proven daily dosing with the intermittent dosing schedule, and, if the increases in axial bone mineral density (BMD) by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) are noninferior to each other, FDA registration can be achieved. Hence, quarterly intravenous ibandronate has become the first intravenous bisphosphonate to be FDA-approved for the treatment of PMO.

The agents that are being considered for either registration for postmenopausal osteoporosis management or are in early clinical development are the newer intravenous bisphosphonates (zolendronic acid) [7]; newer selective estrogen receptor modulators [bazedoxifene (BZA), lasofoxifene, and arzoxifene] [8,9,10,11,12,13]; human monoclonal antibodies to the RANK-ligand system (denosumab) [14]; new parathyroid hormone (PTH) sequences and/or routes of administration (1-84 PTH subcutaneously, 1-31 PTH subcutaneously, 1-34 PTH nasal spray, 1-34 PTH inhaled) [15,16,17,18,19]; and newer non-PTH anabolic agents [20,21]. In even earlier developmental stages, bone agents that might be applicable to the management of PMO are cathepsin K inhibitors, calciolytic agents, agents that alter the Src tyrosine kinase or the sclerostin pathways, and pathways that modulate the WINT pathway 22,23,24,25,26].

WINT is a membrane-bound osteoblast receptor. The WINT pathway is necessary for osteoblastogenesis.

WINT is a membrane-bound osteoblast receptor. The WINT pathway is necessary for osteoblastogenesis.

Table 11.1. Newer therapeutic options in development or under FDA consideration | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

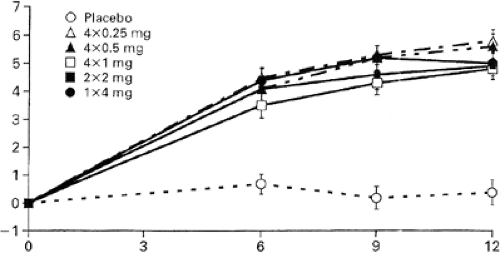

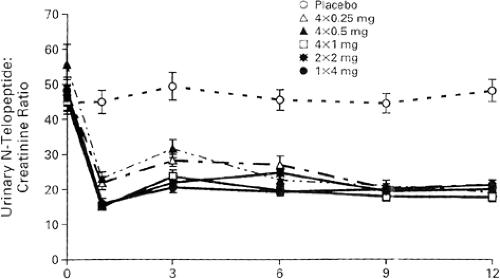

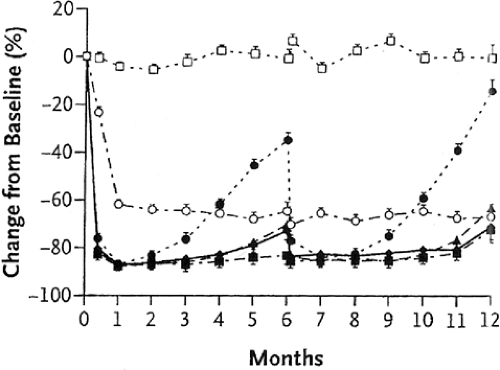

In the initial dose-ranging studies of zolendronic acid, a single intravenous infusion of 4 mg over 15 minutes increased BMD and reduced biochemical markers of bone turnover [N-telopeptide (NTx)], results that were sustained for at least 12 months [7] (Figs. 11.2 and 11.3). Hence, in the FDA application for the treatment of PMO, the suggested dosing frequency will be every 12 months. In clinical practice there seems to be a large heterogeneity to the offset of the long duration of zolendronic effect on bone turnover, as measured by bone resorption markers. In the unpublished offset of zolendronic acid in

the PMO clinical trials, in which the dose will be 5 mg per day, some patients may have a persistent suppression of bone turnover markers far beyond 12 months. It is not known if the label will recommend measuring the urinary cross-linked NTx or serum C-telopeptide of type I collagen (CTx) in order to decide when a second dose of zolendronic acid may be required. Since it is unknown what level of bone turnover is ideal, or if there is a lower level of bone turnover that becomes harmful to bone strength, when the bone turnover is induced by antiresorptive treatment, it is also unclear if the dosing interval of zolendronic acid should be anything other than an every-12-months schedule. If the pending results of the yearly intravenous zolendronic acid clinical trials (HORIZON) show that zolendronic acid in a 5 mg/year dosing interval reduces the risk of fracture, then an annual dose will become the standard dosing interval.

the PMO clinical trials, in which the dose will be 5 mg per day, some patients may have a persistent suppression of bone turnover markers far beyond 12 months. It is not known if the label will recommend measuring the urinary cross-linked NTx or serum C-telopeptide of type I collagen (CTx) in order to decide when a second dose of zolendronic acid may be required. Since it is unknown what level of bone turnover is ideal, or if there is a lower level of bone turnover that becomes harmful to bone strength, when the bone turnover is induced by antiresorptive treatment, it is also unclear if the dosing interval of zolendronic acid should be anything other than an every-12-months schedule. If the pending results of the yearly intravenous zolendronic acid clinical trials (HORIZON) show that zolendronic acid in a 5 mg/year dosing interval reduces the risk of fracture, then an annual dose will become the standard dosing interval.

The second-generation SERMs (selective estrogen selective modulators) are being designed with the purpose of having fewer side effects, especially hot flushes that limit to some degree the wide use of raloxifene. In addition, there is hope that the second-generation SERM agents might have a broader antifracture efficacy beyond reduction in vertebral fractures. Lasofoxifene received an approvable letter from the FDA in 2005 but has not gained FDA approval for PMO, pending additional uterine safety data.

Bazedoxifene has recently been filed for FDA registration. It remains to be seen if the second-generation SERMs will show a similar reduction in breast cancer risks as has been shown with raloxifene [27].

Bazedoxifene has recently been filed for FDA registration. It remains to be seen if the second-generation SERMs will show a similar reduction in breast cancer risks as has been shown with raloxifene [27].

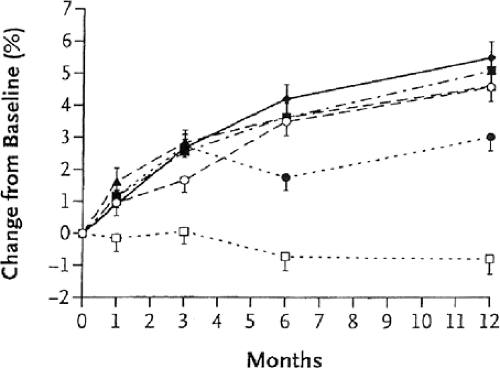

Anti-RANK-ligand antibody (denosumab) has recently been shown to increase BMD and reduce bone turnover markers in phase II clinical trials [14] (Figs. 11.4 and 11.5). The phase III fracture trial is using the dose of 60 mg of denosumab subcutaneously every 12 months for registration. The OPG-RANK ligand–RANK system is intimately involved in the coupling between osteoblastic and osteoclastic regulation. The preosteoblast produces competitive proteins: osteoprotogerin (OPG) and RANK ligand. Depending on which of these two osteoblastic-derived proteins gains access to the osteoclastic membrane receptor rank determines osteoclastic cell differentiation and activity [28]. The anti-RANK-ligand antibody binds to RANK ligand, inhibiting the latter to binding to the receptor rank. The net result is a decrease in bone resorption, a decrease in bone turnover, and an increase in BMD. Because this monoclonal antibody is not retained in bone (as are bisphosphonates), it may allow an alternative approach to the treatment of PMO that may not have the same concerns about long-term bone retention time that bisphosphonates may have.

The alternate PTH anabolic formulations are being designed to offer different routes of administration (nasal, inhaled, and oral), avoiding the daily

subcutaneous injections of the current FDA-approved PTH (teriparatide). In Europe the subcutaneous injection formulation of the 1-84 PTH has been approved for the treatment of PMO. To date, the data from the 1-84 PTH clinical trial show its capacity to reduce the risk of incident vertebral compression fractures in postmenopausal women, both without as well as with a prevalent vertebral compression fracture [15] (Fig. 11.6). These data might lead to consideration of the earlier use of PTH in a lower-risk, postmenopausal population because a plausible hypothesis is to “make new bone” first, with PTH, then to maintain that newly formed bone with an antiresorptive agent.

subcutaneous injections of the current FDA-approved PTH (teriparatide). In Europe the subcutaneous injection formulation of the 1-84 PTH has been approved for the treatment of PMO. To date, the data from the 1-84 PTH clinical trial show its capacity to reduce the risk of incident vertebral compression fractures in postmenopausal women, both without as well as with a prevalent vertebral compression fracture [15] (Fig. 11.6). These data might lead to consideration of the earlier use of PTH in a lower-risk, postmenopausal population because a plausible hypothesis is to “make new bone” first, with PTH, then to maintain that newly formed bone with an antiresorptive agent.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree