Flexible Intramedullary Nailing of Femoral Shaft Fractures

Christine M. Goodbody

John M. Flynn

DEFINITION

Femoral shaft fractures in children occur with an incidence of 20 per 100,000.3, 9, 14 They constitute 2% of all pediatric fractures.11

In a very young child who presents with a femoral shaft fracture, child abuse must be considered, especially if the child is not yet walking.2 In the young child who has a history of multiple fractures or fracture after minimal trauma, osteogenesis imperfecta might be the underlying cause and is often mistaken for child abuse.

In children who sustain multiple traumatic injuries, the nature and severity of each injury must be considered in order to prioritize and optimize treatment.

ANATOMY

During childhood, the femur is initially composed of weaker woven bone, which is gradually replaced with lamellar bone.

The profunda femoris artery gives rise to four perforating arteries, which enter the femur posteromedially. The majority of the blood is supplied by the endosteal circulation. During fracture healing, however, the majority of the blood is supplied by the periosteal circulation.

The femoral shaft flares distally, forming the supracondylar area of the femur. This area serves as the entry point for retrograde nailing with flexible intramedullary nails. Surgeons should maintain an awareness of the nearby distal femoral physis, which can be injured during nail insertion.

PATHOGENESIS

Age is an important factor to consider in terms of the pathogenesis of the injury. The degree of trauma required to cause injury increases exponentially, as the character of the bone changes and gradually becomes stronger and larger from infancy to adolescence. Low-energy injuries resulting in fractures may point to a pathologic nature of the condition.

The radiographic appearance of the fracture usually reflects the mechanism of injury and the force applied. High-velocity injuries usually present with more complex, comminuted patterns.

The position of the fracture fragments after the injury depends on the level of the fracture and reflects the soft tissue and muscle forces acting on the femur.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

In most cases, there is a history of a traumatic event.

In an isolated femur fracture, the thigh appears swollen, with minor bruises and abrasions. Shortening may also be present.

The affected extremity should be checked to ensure that no vascular or neurologic injury is present.

In cases of high-energy trauma, concomitant injuries to the skin and soft tissue as well as other organ systems are usually present.

An examination of the knee should be performed to ensure that no ligamentous injury is present. This may be performed under anesthesia.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

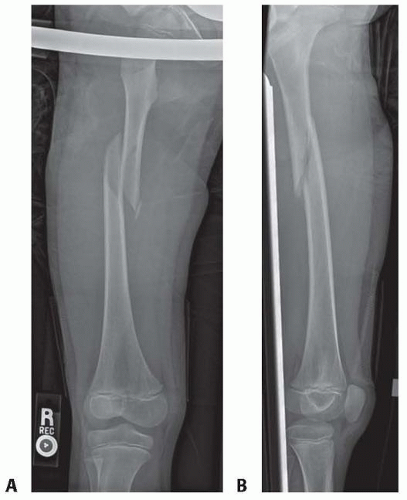

Standard high-quality anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the femur are usually all that is needed to define the extent and severity of the injury (FIG 1).

Radiographs should include the joints above and below the fracture site to avoid missing any concomitant injuries.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Acute traumatic fracture in normal bone

Stress fracture

Pathologic fracture

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Elastic nailing of the femoral shaft is the optimal treatment for most femur fractures in children 5 to 12 years old.

In rare cases in the 5- to 12-year-old age group, children with very length-unstable fractures, or older children who are very

heavy, are best treated with another method (submuscular plating, external fixation, or trochanteric entry nailing, described in other chapters).

Elastic nailing can be used in skeletally immature adolescents, especially for length stable fractures in children less than 50 kg, although there is a slightly higher rate of loss of alignment, delayed healing, and poor results than in younger children.

In very rare circumstances, elastic nailing can be used in children 3 to 5 years old. Possible indications include very high energy injury, soft tissue injury that makes casting risky, very obese preschool children, or polytrauma.

Preoperative Planning

The diameter of the nails is predetermined by measuring the isthmus of the femoral shaft. The nail size to be used is usually 40% of the narrowest diameter. For instance, if the isthmus measures 1 cm, two 4-mm nails are used.

The presence of concomitant injuries should be considered as well as factors that may hinder or complicate treatment.

Positioning

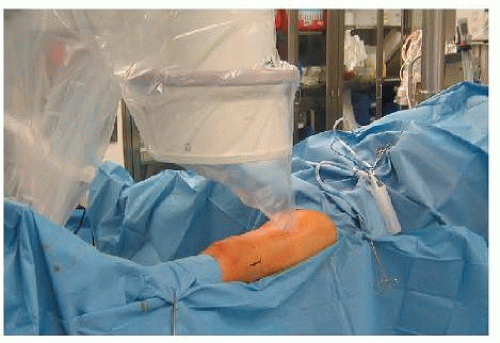

The patient is positioned in the supine position. We prefer using a fracture table (FIG 2), although a radiolucent table may be used as well.

The groin area is adequately padded before application of the post.

The affected extremity is abducted 15 to 30 degrees to allow room for nail placement. The uninjured leg can be held by the ankle (the well-foot holder) and “scissored” with extension of the hip so that it does not block the lateral radiographic view.

We generally avoid the well-leg holder that places the hip and knee flexed high above the rest of the patient. Compartment syndrome has been associated with this positioning for femoral shaft fracture treatment.

A distraction force is applied to the affected extremity through the foot using a foot holder. If there is significant soft tissue injury to the leg, the distraction force may be applied through a traction pin. However, this is rarely necessary in children.

Ideally, the fracture should be brought out to length and reduced to as near an anatomic position as possible before prepping and draping. Time spent optimizing alignment in the unprepped patient generally pays large dividends in time saved struggling with the fracture reduction just before the nail is passed across the fracture site.

The extremity is then prepared and draped.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Retrograde Flexible Intramedullary Nailing

Nail Introduction and Fracture Reduction

The nail entry sites, which are located on the medial and lateral aspects of the distal femoral metaphysis, are identified using an image intensifier.

The distal femoral physis is identified, and this position is marked on the skin to remind the surgical team to avoid the dissection in this area.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree