Finger Dislocation

Pramod B. Voleti

Stephan G. Pill

David R. Steinberg

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The joints of the hand are subjected to significant forces during the course of daily activity. While these joints are well adapted for stability and mobility, they are susceptible to injury from excessive external forces, which can result in bony, ligamentous, and capsular injury and lead to varying degrees of subluxation or dislocation. Dislocations of the finger are relatively common and occur when two articulating bones in the digit are displaced from their normal anatomic position relative to one another. These dislocations can occur at the MCP joint, the PIP joint, and/or the DIP joint. The PIP joint is the most commonly dislocated joint in the body.1 Patients with dislocated finger joints typically present with a history of trauma leading to finger pain, swelling, and deformity, as well as reluctance to move the affected digit. The most common mechanism of injury is hyperextension, resulting in a dorsal dislocation and injury to the volar plate and the collateral ligaments.2 However, finger dislocations can occur in any direction, and determining the exact mechanism of injury could help to identify other structures that may be injured. Dislocations can range from an athlete’s “jammed finger,” in which a lesser degree of force may result in only a sprain of the periarticular ligaments and joint capsule and/or a tendon avulsion, to an irreducible fracture dislocation, in which a greater degree of force may result in more significant bony, ligamentous, and capsular injury.

CLINICAL POINTS

The PIP joint is the most commonly dislocated joint in the body.

Finger dislocations typically result in severe pain and reluctance to move the affected digit.

Finger dislocations may occur in any direction, coinciding with the direction of trauma.

Finger dislocations may occur with associated fractures or ligamentous injuries.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

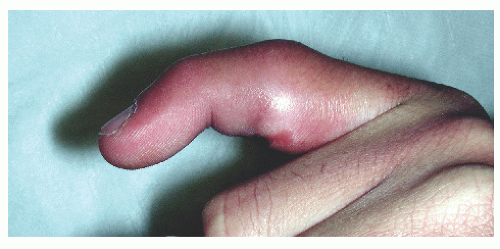

Patients with finger dislocations typically present with swelling, deformity, and tenderness of the involved digit. A finger dislocation should be suspected in any patient with this constellation of findings following a traumatic injury. The deformity should correspond to the direction of injury; for example, a dorsal PIP dislocation will typically present with hyperextension or dorsal translation of the middle phalanx relative to the proximal phalanx (Fig. 52-1). The exact location of tenderness may help elucidate the direction of dislocation. In a dorsal PIP dislocation, the volar plate is usually damaged, thus resulting in tenderness over the volar aspect of the PIP joint. On rare occasion, the volar plate may rupture proximally and become interposed between the head of the proximal phalanx and the base of the middle phalanx, resulting in an irreducible dislocation. In contrast, a volar PIP dislocation is commonly associated with rupture of the central slip (extensor tendon attachment to the base of the middle phalanx), thus resulting in tenderness over the dorsal aspect of the PIP joint (Fig. 52-2). A thorough assessment of active and passive range of motion at all joints should be undertaken upon presentation. This careful examination is necessary to rule out extensor or flexor tendon avulsion injuries. Instability to varus and valgus stressing may be present. Stress testing and a careful evaluation for angulation are critical to rule out damage to one or both of the collateral ligaments. Rotatory subluxation can be assessed by examination of the nails, as they should all lie in the same plane. A nail rotated out of the plane of the other nails signifies a rotational deformity.

Injuries at the DIP joint commonly result in rupture of the terminal slip of the extensor tendon (“mallet finger”) (Fig. 52-3).2 Less common but much more difficult to diagnose is rupture of the flexor profundus tendon at its attachment to the base of the distal phalanx. This may be easily confused with a sprained DIP joint, as both result in a swollen, stiff, painful joint. With an acutely injured joint, a patient can be coaxed into gently flexing the DIP joint if the examiner supports the middle phalanx. Even a slight amount of active flexion is evidence of an intact flexor mechanism. If the examiner suspects a ruptured flexor tendon, or if the exam is equivocal, early consultation with a hand surgeon is advised; these injuries must be surgically repaired within 1 to 3 weeks. Dislocations of the DIP joint are often associated with an open wound because of the tautly fixed skin about the joint.2

The MCP joints of the finger are relatively resistant to ligament injury and dislocation because of their protected position at the base of the finger, their intrinsic ligamentous support, and their external supportive structures.2 Nevertheless, significant forces (particularly those directed ulnarly and dorsally) may result in dislocation of the MCP joint.2 The most commonly involved digit is the index finger, followed by the small finger.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree