Fibromyalgia and Regional Pain Syndromes

Joan M. Von Feldt

Jonathan Dunham

Lan X. Chen

Fibromyalgia is a common cause of chronic musculoskeletal pain. It is one of a group of soft tissue pain disorders that affect muscles and soft tissues such as tendons and ligaments. Fibromyalgia is not associated with tissue inflammation, and the etiology of the pain is not known.

Fibromyalgia is likely the most common cause of generalized, musculoskeletal pain in women between 20 and 55 years of age, with a prevalence of 2%.1 It is usually associated with sleep disturbance and nonrestorative sleep. The precise pathophysiologic mechanism of fibromyalgia is unclear. However, some aberrancy in central nervous system function is likely. In fact, patients with fibromyalgia have higher levels of substance P, a neurotransmitter involved in pain transmission, in their cerebrospinal fluid.2 The exact trigger of fibromyalgia is unknown, but it is possible that some psychosocial stressor may be important.

CLINICAL POINTS

The condition is probably the most common cause of generalized musculoskeletal pain in women.

Pain may be widespread and diffuse.

Associated fatigue is usually present.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

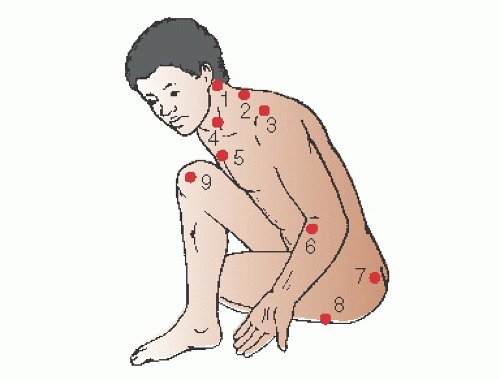

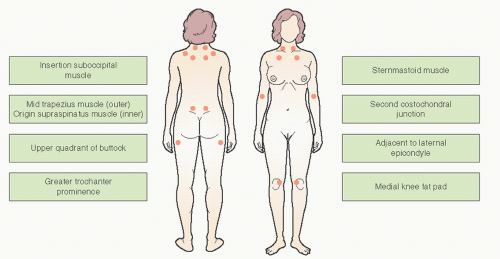

The major criteria for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia include (a) widespread musculoskeletal pain and (b) excess tenderness in at least 11 of 18 tender points, in association with nonrestorative sleep. Tender points are predefined anatomic sites in the muscles of the upper and lower back and extremities that are excessively tender on manual palpation (Fig. 63-1). Excessive tenderness is defined as eliciting pain when the examiner applies a digital force of 4 kg/cm2 to a fibromyalgia tender point or enough pressure to result in blanching of the fingernail of the examiner. Although most patients give a history of frequent waking throughout the night, some patients do not recall a poor sleep pattern but awaken in the morning with nonrestorative sleep. This is due to a sleep arousal disorder, with disruption of deep sleep, or EEG-measured alpha wave intrusion on delta wave sleep, which is frequently found in patients with fibromyalgia.3

Patients with fibromyalgia frequently have accompanying fatigue, and their fatigue is disproportionate to amount of time resting and sleeping. They describe moderate or severe fatigue with lack of energy and decreased exercise endurance. Often, the fatigue is more of a problem and more troubling than the pain. Since they feel fatigued, patients usually will exercise less, exacerbating the poor sleep.

Fibromyalgia is a diagnosis of exclusion, and systemic conditions need to be considered in evaluating a patient with diffuse pain. Additionally, since a sleep disturbance can coexist with many rheumatic disorders and many rheumatic and

systemic illnesses present with generalized arthralgias, myalgias, and fatigue, rheumatic conditions need to be carefully considered in a patient with diffuse pain. Also, fibromyalgia can coexist in patients with rheumatic disorders. For example, 25% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus can have coexistent fibromyalgia.4

systemic illnesses present with generalized arthralgias, myalgias, and fatigue, rheumatic conditions need to be carefully considered in a patient with diffuse pain. Also, fibromyalgia can coexist in patients with rheumatic disorders. For example, 25% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus can have coexistent fibromyalgia.4

In evaluating a patient with diffuse pain, some practitioners find it helpful to provide an anatomic figure and ask the patient to identify areas of pain. The more diffuse the pain, the more likely it is to be fibromyalgia. A patient with polyarticular arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, will identify the articulations as painful but will rarely point to muscles or the back.

The initial approach to a patient with complaints suggestive of fibromyalgia is a thorough history and physical examination. Sleep apnea and restless leg syndrome or nocturnal myoclonus may interfere with sleep and promote symptoms of fibromyalgia.5 Thus, a careful sleep history should be obtained in patients with fibromyalgia symptoms. Also, a psychiatric history may be important to look for concomitant mood disorders, as these are prevalent in patients with fibromyalgia. Careful examination of the joints and muscles and testing for tender points is very important.

STUDIES (LABS, X-RAYS)

Baseline blood tests should be limited to a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, standard blood chemistries, thyroid function tests, and creatinine kinase (CPK)— especially when patients are taking concomitant cholesterol lowering agents such as statins. With certain risk factors, it would be suggested to check human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis serologies. These tests are all usually normal in patients with fibromyalgia, and any abnormalities might suggest the presence of an alternative diagnosis. Patients with possible sleep apnea or nocturnal myoclonus should be referred to a sleep clinic for further evaluation and treatment.

Systemic diseases to be considered in patients presenting with fibromyalgia:

Hypothyroidism and other endocrine disorders (e.g., diabetes, Addison disease, growth hormone deficiency)

Chronic hepatitis B and C infections

Sleep disorders such as sleep apnea and restless leg syndrome

Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, sjögren syndrome, polymyalgia rheumatica, and other autoimmune diseases

Medications (especially lipid-lowering drugs, antiviral agents)

Vitamin D deficiency

Celiac disease

Malignancy

REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROMES (MYOFASCIAL PAIN SYNDROMES)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree