Femoral Rotational Osteotomy (Proximal and Distal)

Robert M. Kay

DEFINITIONS

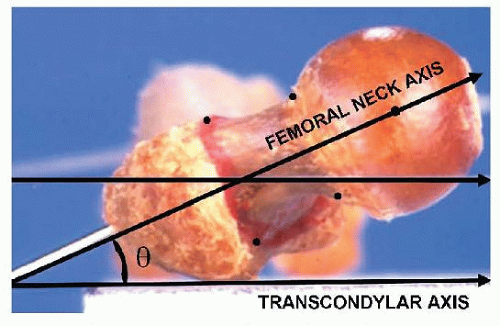

Femoral anteversion is the angle in the transverse (rotational) plane between the neck of the femur and the distal femur, as defined by the intercondylar axis.

The term femoral torsion may be used in lieu of femoral anteversion and is favored by those who believe that the torsion often occurs in the femoral shaft rather than the neck.6, 23

Because the femoral neck is typically directed anteriorly, the vast majority of people have femoral anteversion. Femoral retroversion is rare and is present when the neck is directed posteriorly.

ANATOMY

Femoral anteversion is measured as the angle of the femoral neck relative to the distal femoral transcondylar axis. The transcondylar axis is measured along the posterior distal femoral condyles (FIG 1).

PATHOGENESIS

Femoral anteversion varies throughout growth and development, both prior to and after birth.

Femoral anteversion predominates in all age ranges and peaks at birth at a mean of 30 to 50 degrees, decreases to approximately 20 degrees by age 10 years, and 15 degrees by age 15 years.2, 7

During normal development, forces between the hip and anterior iliofemoral ligaments with the hip extended appear to lead to the decrease in femoral anteversion.

The natural remodeling process may be impaired in a variety of circumstances leading to persistent increased femoral anteversion in conditions including developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), cerebral palsy (CP), and Legg-Calvé-Perthes.7, 12, 20, 24, 25

FIG 1 • Femoral anteversion is the angle in the transverse plane by which the neck of the femur is directed (forward) relative to the transcondylar or coronal plane.

Femoral anteversion can have a genetic component and has a predilection to occur in certain families.

NATURAL HISTORY

Physiologic Anteversion

As noted, femoral anteversion decreases from 30 to 50 degrees at birth to approximately 20 degrees by age 10 years and 15 degrees by age 15 years.2, 7

Despite these mean values, variability is significant, and femoral anteversion is a common cause of persistent intoeing gait in children.7, 10

In typically developing children, persistent femoral anteversion is rarely of functional consequence because they have normal balance, strength, and coordination.

Occasionally, the combination of persistent femoral anteversion and external tibial torsion (so-called “malignant malalignment”) may be seen in a child. If this combination results in significant patellofemoral pain and/or patellar instability, osteotomy may be indicated.5, 16

Cerebral Palsy

CP affects approximately 1 in 500 children in the United States and is associated with motor and cognitive delays.

CP has long been known to be associated with increased femoral anteversion throughout childhood, thought to be due to developmental delays, contractures and abnormal forces across the hip.3, 4, 9, 15, 20

More recent work has shown that the strongest correlation with femoral anteversion in children with CP is the Gross Motor Functional Classification System (GMFCS) level.20 For children functioning at GMFCS I, anteversion is near normal, and anteversion increases in a stepwise fashion in GMFCS II and III children, being significantly persistently elevated in GMFCS III, IV, and V children.

Femoral anteversion (with resultant internal hip rotation during gait) is a common cause of intoeing in ambulatory children with CP and contributes to lever arm dysfunction and crouch gait in these children.15, 18, 19

In children with severe nonambulatory CP (GMFCS IV and V), increased anteversion and coxa valga are features of the hip at risk for subluxation or dislocation.20

Increased anteversion is a component of malignant malalignment syndrome, which has been implicated as a source of patellofemoral pain and instability.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Parents often note that children with anteversion often sit in a “W” position and may have difficulty sitting cross-legged (FIG 2).

Intoeing is common in children with persistent femoral anteversion, including typically developing and special needs children.7, 10

Intoeing in typically developing children typically does not result in functional limitations, although it frequently results in significant functional deficits (including tripping and falls) in special needs children, such as those with CP.9, 19

Internal hip rotation during gait results in internal knee progression angle throughout the gait cycle.

In most children with internal hip rotation during gait, the foot progression angle is also internal.

Foot progression angle may be neutral (or external) if femoral anteversion and internal hip rotation are combined with ipsilateral external tibial torsion and/or significant pes valgus deformity. (The combination of femoral anteversion and external tibial torsion is known as malignant malalignment.)

The rotational profile of the entire limb is checked with the child in the prone position.

In the presence of increased femoral anteversion, hip internal rotation markedly exceeds external rotation.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A number of imaging techniques have been described to estimate femoral anteversion, including plain radiography, fluoroscopy, computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).1, 11 None of these tests is routinely necessary in the assessment of children with femoral anteversion.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Increased anteversion is most commonly encountered in the following situations:

Isolated “idiopathic” femoral anteversion

Malignant malalignment syndrome

CP

DDH

In addition to femoral anteversion, other common causes of intoeing include the following:

Tibial torsion

Foot deformity (including pes varus and/or metatarsus adductus)

Internal pelvic rotation (in some neuromuscular diseases)18

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

There is no nonoperative intervention which changes the rotational profile of the long bones.

Nonoperative treatment of intoeing is geared toward trying to get the child to position the affected hip(s) in more external rotation during gait. Such interventions may include mechanical devices such as twister cables or derotation straps or use of a home program to teach the child to actively externally rotate the hip(s).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications

The most common indication is persistent femoral anteversion associated with intoeing interfering with function in children with CP. The anteversion and intoeing typically impact function by causing tripping and/or lever arm dysfunction.

Isolated idiopathic femoral anteversion rarely requires surgical correction. The rare exceptions are children at, or nearing, adolescence with severe anteversion accompanied by marked internal foot and knee progression angles resulting in functional limitations.

Malignant malalignment (the combination of femoral anteversion and external tibial torsion) results in anterior knee pain and/or patellar instability recalcitrant to nonoperative measures.

Preoperative Planning

Location of the Osteotomy

The first decision which should be made in planning femoral rotational osteotomy is whether to perform the osteotomy proximally or distally.

Benefits of a distal femoral osteotomy fixed with Kirschner wires (K-wires) include (1) smaller incision, (2) less soft tissue dissection, and (3) no need for reoperation for retained hardware (as the K-wires are removed in the office 1 month postoperatively).14, 15

Benefits of a proximal femoral osteotomy (typically fixed with a blade plate) include (1) rigid internal fixation and (2) the ability to correct coxa valga and hip subluxation by including a varus component when planning and performing the osteotomy.14, 15

Given the relative merits of the two techniques, distal femoral osteotomies are preferred for pure rotational correction in children before adolescence.

Proximal femoral osteotomies are typically preferred for children with coxa valga (often with associated hip subluxation, as in CP, DDH and/or Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease) and in children nearing adolescence (in order to avoid casting).

Even when a distal femoral osteotomy is being considered, an anteroposterior (AP) pelvis x-ray should be performed preoperatively to make sure that there is no significant hip uncovering requiring a proximal femoral osteotomy.

Amount of Correction

Preoperatively, the surgeon determines the amount of intraoperative rotational correction to be performed based on both physical examination measurements and the assessment of gait.

It is imperative that other deformities impacting transverse plane kinematic (rotational) data are thoroughly assessed.8, 14, 15 These include pelvic asymmetry and rotation, tibial torsion, and any foot deformities.

Remember that pes valgus contributes to outtoeing, and pes varus contributes to intoeing.

Physical examination (as described earlier) allows quantification of osseous deformity in these children. Radiographic imaging to assess rotation is not typically necessary.

Gait should be assessed thoroughly, preferably with a computerized gait study, in order to quantify the contributors to transverse plane alignment, including pelvic rotation, hip rotation, tibial torsion, and foot deformity. Although gait analysis is most commonly thought of for children with CP (or other neuromuscular maladies), it is also helpful to quantify gait deviations in typically developing children with significant torsional malalignment who are being considered for surgical intervention.

The amount of rotation performed at surgery is based on the static and dynamic measures. Typically, the distal fragment should be rotated 1.5 to 2.0 times the amount of abnormal internal hip rotation on gait preoperatively.15, 17 (For example, if there is 20 degrees of internal hip rotation preoperatively, the femur should be rotated 30 to 40 degrees intraoperatively.) Less derotation results in undercorrection.

If a proximal femoral osteotomy is planned (based on patient age and/or radiographic findings of coxa valga and/or hip subluxation), plain pelvis radiographs facilitate the planning regarding any varus correction to be incorporated into the osteotomy.

Hardware Choice

Proximal Femoral Osteotomy

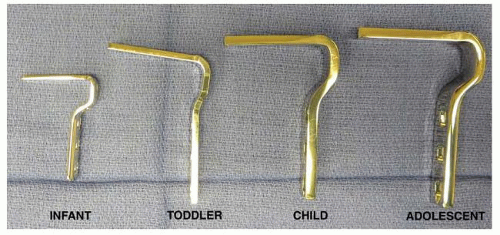

Proximal femoral osteotomies are typically fixed with blade plates. A plate should be chosen with a long enough blade to ensure stable fixation while stopping short of the proximal femoral physis (FIG 3).

For small children, a rough guide for AO (Synthes, Paoli, PA) blade plate size follows:

Less than or equal to 18 kg: AO “infant” blade plate

Eighteen to 24 kg: AO “toddler” blade plate

Greater than or equal to 25 kg: AO “child” blade plate

Distal Femoral Osteotomy

Three or four 2.4-mm (3/32 inches) K-wires are typically used for fixation.

Positioning

Proximal and distal femoral osteotomies are both easily accomplished with the patient supine on a radiolucent operating table. Supine positioning also facilitates the performance of numerous other concomitant procedures, particularly in children with CP or other neuromuscular diseases.

Some other authors advocate the prone position for proximal femoral osteotomies and cite the ability to perform the same intraoperative assessment of the torsional profile as the preoperative assessment.21

Prone positioning precludes pelvic osteotomy and hip flexor lengthening.

Approach

Proximal Femoral Osteotomy

A standard lateral approach is used.

The proximal end of the incision is at the level of the vastus ridge (origin of the vastus lateralis).

Distal Femoral Osteotomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree