Abstract

Objectives

Retrospective study over the last 30 years of life expectancy in patients suffering from Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Analysis of the role of ventilatory assistance and causes of death.

Patients and methods

One hundred and nineteen adult DMD patients were hosted during 1981 to 2011 at AFM Yolaine de Kepper centre, Saint-Georges-sur-Loire, France. Patients’ life expectancy was calculated using Kaplan-Meier model.

Results

Life expectancy without or with ventilatory assistance was 22.16 and 36.23 years, respectively. Similarly, life expectancy of patients born from 1970 (mostly with ventilatory assistance) was 40.95 years old from 1970 and 25.77 years old before 1970. Causes of death changed. Cardiac origins of death have increased from 8% to 44%.

Conclusion

Ventilator assistance, in this study mostly through tracheotomy prolongs by more than 15 years life expectancy of DMD patients. It allows conservation of a satisfactory quality of life, and should be systematically proposed to patients.

Résumé

Objectifs

Étude rétrospective sur 30 ans de l’espérance de vie des patients atteints de dystrophie musculaire de Duchenne (DMD). Analyse du rôle de la ventilation assistée et des causes de décès.

Patients et méthodes

Cent-dix-neuf patients adultes atteints de DMD ont séjourné au centre AFM Yolaine de Kepper, Saint-Georges-sur-Loire (France) entre 1981 et 2011. L’espérance de vie des patients a été calculée en utilisant le modèle de Kaplan-Meier.

Résultats

L’espérance de vie des patients atteints de DMD sans ventilation assistée était de 22,16 ans et de 36,23 ans pour ceux qui en ont bénéficié. L’espérance de vie des patients nés à partir de 1970 (et ainsi le plus souvent ventilés) était de 40,95 ans et d’uniquement 25,77 ans pour ceux nés avant 1970. Les causes de décès se sont également modifiées avec une progression des décès d’origine cardiaques de 8 % à 44 %.

Conclusion

La ventilation assistée et dans cette étude principalement par trachéotomie, permet de prolonger l’espérance de vie de plus de 15 ans des patients atteints de DMD. Elle permet de conserver une qualité de vie satisfaisante et doit être systématiquement proposée aux patients.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common muscular dystrophy. It is a recessive X-linked disease which affects one every 3500 male births. DMD results from the absence of one particular protein, called dystrophin, in myocytes, which leads to loss of membrane integrity, followed by progressive destruction of the muscle fibber.

Clinical signs usually develop between 2 and 5 years of age, with patients experiencing difficulty running, climbing stairs and frequent falls. Cognitive impairment may also be present in 30% of cases. Weakness and muscle wasting, originally present mostly in the pelvic girdle, progressively extends to all muscles. Indeed, Gowers sign (children use of their arms to push themselves erect by moving their hands up their thighs. This permits assuming a standing position from one of kneeling) is observed at a median age of 5 years and walking becomes waddling.

As the deficit worsens, falls become more frequent with impossibility to stand up. Independent walking becomes impossible in most cases between 9 and 13 years Contractures worsen in the lower and upper limbs. Severe scoliosis occurs, which often requires spinal arthrodesis. Motor deficit continues worsening with reduction of autonomy for simple acts of daily life. Loss of ability to self-feed only occurs around age 18.

Before onset of ventilatory assistance by tracheotomy or NIV, death occurred typically between 16.2 and 19 years, and almost always before age 25 mainly due to terminal respiratory failure, main cause of death. Indeed vital capacity (VC), which progresses normally up to 9 to 10 years of age, increases only slightly and slowly after this age, and finally decreases by 5 to 10% per year after age 14 with gradual onset of restrictive respiratory failure, which leads in most cases to death at age 18 in absence of ventilatory assistance. .

Hypoventilation and hypercapnia first occur during sleep . At this time, VC is usually at 20 to 50% of normal values, and implementation of NIV showed no benefit for survival .

Appearance of diurnal hypercapnia follows this initial period, and without ventilatory assistance, mean survival in DMD is less than 1 year .

So, for DMD patients ventilation onset is deciced if:

- •

either VC inferior to 20%, a Pa CO2 superior to 45 mmHg or two episods of acute respiratory failure ;

- •

or VC inferior to 680 mL and maximal inspiratory pression (MIP) inferior to 3,5 kPa (predictive of diurnal hypocapnia) .

Gradually, ventilation duration is majored during the day, usually with a mouth piece. Dependance for permanent ventilation is often around 23 years old when VC is around 320 mL .

A tracheotomy is proposed for non-feasibility or wish of the patient. Most often, it has been realized because of an uncontrollable obstruction despite cough assistance or due to major problems with swallowing or feeding difficulties.

The alternative cause of death is dilated cardiomyopathy, which can begin around age 5, become symptomatic at 15 (diagnosis of cardiomyopathy is evident at 14.4 ans (± 2.3 years) in the study of Connuck et al. ) and is almost systematically present after age 18. The evolution of dilated cardiomyopathy is not correlated with the extend of skeletal and respiratory muscle involvement. Myocardiopathy treatment (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and eventually associated betablokers) is recommended from age of 10 . Corticosteroid therapy was shown to slow down myocardiopathy evolution .

The aim of the present study is to measure the evolution of life expectancy that occurred in the last 30 years at the center of AFM Yolaine de Kepper (France) where patients with DMD have been since 1981, temporarily or permanently. The share of ventilatory management that began in some centers in the late 1970s, but a more systematic way between 1985 and 1990 as well as the causes of death were also studied.

1.2

Patients and methods

1.2.1

Patients

All temporary or permanent residents labelled DMD at AFM Yolaine de Kepper centre between 1981 and September 2011 were included in this retrospective study.

The youngest patient included was born in March 1955, the eldest in 1994.

The AFM center accepts only adult (> age 18) patients. The center AFM is currently a specialized residence (MAS) which hosts as a permanent and as a temporary residence (for periods most often 1 to 3 months). Recruitment of the center during these years was national with regional predominance. Decisions and treatment options including assisted ventilation, tracheotomy or gastrostomy were done for some patients while residing at the center AFM. The choices offered by the referring physicians in the CHU d’Angers as well as the center’s physicians have been validated by the patient himself or by representative persons. For temporary residents, the decision was made in other centers except where respiratory failure occurred during their stay.

Of the 131 patients born between 1955 and 1994 labelled DMD who stayed at the centre, 36 had a confirmed diagnosis (biopsy confirming absence of dystrophin or genetic test) of DMD. Certainty of diagnosis was impossible before 1987, and therefore many patients did not initially have a definitive diagnosis.

In the absence of confirmatory diagnosis, the following criteria were used prior to 1987 to distinguish DMD from other muscular dystrophies and in particular from milder forms of dystrophinopathy like Becker muscular dystrophy: mode of transmission, clinical and paraclinical history compatible with DMD (biopsy, EMG, CPK, early disorders, age of loss of independent walking prior to 13 years, need for assisted ventilation at or before age 26 or death before that date in the absence of assisted ventilation). Eighty-three patients complying with all the above criteria were included and considered probable DMD patients. Twelve patients born between 1951 and 1972 were not included in the study because they did not comply with at least one criteria or because of lack of sufficient information.

None of the 119 patients in the study received corticosteroid treatment, currently considered as recommended treatment .

1.2.2

Statistical analysis

A Kaplan-Meier model was used for survival analysis. Comparison of survival curves was performed by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test and the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

Population

At September 15 2011, 55 patients died, 36 were alive and 28 lost to follow-up.

1.3.2

Change in life expectancy for patients born after 1970

The year 1970 was chosen as cut-off for this analysis because ventilation was progressively introduced at the AFM centre between 1985 and 1990 for patients around 18 years of age.

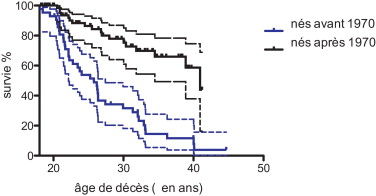

The median survival for the 76 DMD patients (with or without ventilatory assistance) born after 1970 was 40.95 years and 25.77 years for those born before 1970 ( Fig. 1 ).

Comparison of two survival curves by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test and the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test found a significant difference with P < 0.0001.

1.3.3

Change in life expectancy with and without ventilatory assistance

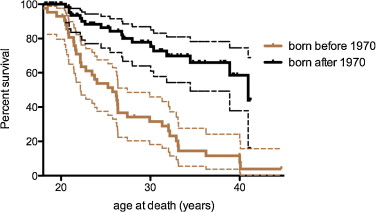

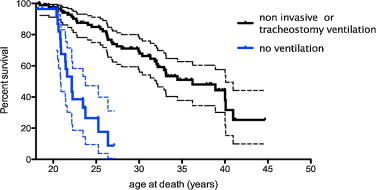

The median survival found by Kaplan-Meier analysis for all DMD patients was 36.23 years (95% CI 37.81–62.7%) for those who received ventilatory assistance and 22.16 for the others ( Fig. 2 ).

A comparison of the two survival curves by the methods of the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test and the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test found a significant difference with P < 0.0001.

1.3.3.1

Mean age of death

The mean age of death was 21.82 years (standard deviation, SD ± 2.11) for patients without ventilatory support and 28.25 years (SD ± 6.07) for ventilated patients.

1.3.3.2

Age at start of ventilation

The mean age at onset of NIV was 20.09 years (SD ± 4.05) and 21.66 (SD ± 3.72) for tracheotomy ventilation for the 77 tracheotomised patients. The first tracheotomy dates 1981 and the first NIV 1983.

Among the 43 patients born before 1970, the average age of completion of the tracheotomy was 22.22 years. It has not been changed for the 53 patients born between 1970 and 1980 to 22.20 years and decreased surprisingly for 23 patients born after 1980 to 19.81 years. For the latter, 19 of 24 (79%) received NIV or tracheotomy. For those born between 1970 and 1980, 44 of 53 (83%) benefited.

For those born before 1970, they were only 26 of 43 (60%) mainly born in 1965 ( Tables 1 and 2 ).

| Patients | Number of patients | Median age at initiation of NIV | Median age at tracheotomy |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 119 | 20.09 | 21.66 |

| Born before 1970 | 43 | 20.9 | 22.22 |

| Born between 1970 and 1980 | 53 | 20.32 | 22.20 |

| Born after 1980 | 23 | 18.34 | 19.8 |

| Patients | Number of patients | No ventilation | NIV exclusive | NIV and tracheotomy | Only tracheotomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 119 | 42 (35%) | 12 | 23 | 54 |

| Born before 1970 | 43 | 17 (40%) | 5 | 9 | 12 |

| Born between 1970 and 1980 | 53 | 9 (17 %) | 3 | 10 | 31 |

| Born after 1980 | 23 | 4 (17 %) | 4 | 4 | 11 |

When tracheotomy followed the initiation of NIV, she followed after 3.48 years (SD ± 2.78) tracheotomy ventilation was 14.34 years.

1.3.4

Life expectancy after onset of tracheotomy ventilation

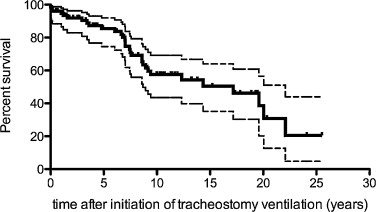

Life expectancy after tracheotomy was 17.17 years (77 patients) ( Fig. 3 ).

1.3.5

Causes of death

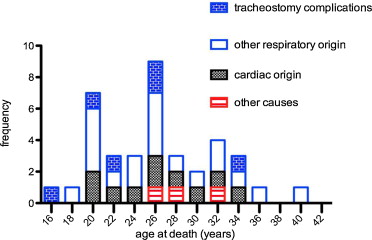

The cause of death was recorded for 37 out of the 55 patients who died ( Fig. 4 ).

A cardiac origin is suspected in 10 patients (27%) who had documented advanced heart failure and lack of respiratory decompensation. Two additional patients died with cachexia associated with heart failure and one patient from septic shock.

For 25 out of 37 patients (67.5%), death was caused by end-stage respiratory failure, a major congestion or accidents or complications related to ventilatory assistance or tracheotomy. Among these 25 patients, we found six tracheotomy complications (16.2% of all deaths and 24% of respiratory associated deaths). Four patients experienced endotracheal bleeding, a complication of cryotherapy granuloma and one extrusion of tracheotomy. Two subjects died of ventilation interruption (ventilator failure and accidental disconnection).

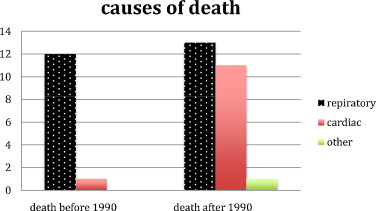

From 1990, most of the patients had ventilatory assistance. Before 1990, 12 (57%) of the 21 patients died from respiratory-linked complications and only one (4,8%) from cardiac related disease. From 1990, 13 (38%) of the 34 patients died from respiratory-linked complications and eleven (29%) from cardiac related disease and one from septic shock ( Fig. 5 ).

1.4

Biases of the study

Patients younger than 18 were not admitted at the centre, and therefore survival curves should be interpreted from the age of 18 only.

The relatively large number of patients lost to follow-up results in a significant number of events censored in the Kaplan-Meier analysis, and increases the variance of estimated treatment effects. The 95% confidence interval is therefore indicated in the figures.

1.5

Discussion

1.5.1

Prolongation of survival

Associated with a shift from respiratory- to cardiac-related causes of death, mainly due to implementation of ventilatory care, we have observed an important prolongation of survival in our DMD patients. At the opening (1981) of the AFM centre at Saint-Georges-sur-Loire, ventilatory assistance was only exceptionally implemented and only seven DMD patients had been ventilated (four tracheotomy ventilation and three NIV) before 1985. Use of ventilatory assistance grew rapidly to become almost systematic between 1985 and 1990. This evolution explains in our opinion the increase of life expectancy for patients born after 1970.

Results published by rehabilitation centres which did not propose assisted ventilation to DMD patients until the early 2000s can be compared with those obtained at the AFM centre for patients without ventilatory assistance or for those all patients born before 1970. In our study, median survival was 21.6 years for DMD patients born before 1970, and 38% of patients reached age 23. These figures are higher than those published in other studies, but we need to remember that the AFM centre only recruits patients older than 18 years of age, and that therefore mortality before this age in unaccounted for.

Other factors, such as improved nutritional care, spinal arthrodesis and support systematic cardiological contribute to the prolongation of life expectancy.

So Eagle et al. with 100 patients born between 1970 and 1990 highlight the importance of spinal arthrodesis allows ventilation with a life expectancy of only 30 years and 22 years without arthrodesis.

However, no significant extension is found in different studies without assisted ventilation.

In England and Wales , utilization of assisted ventilation was low until 1999, and the life expectancy of DMD patients was only 18.5 years. Quasi-absence of ventilatory assistance was also the norm in Holland even after 2000. In centres such as the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, USA where overall patient care improved overtime but where NIV was not systematically put in place, life expectancy of DMD patients born in 1983 was the same as for those born in 1953 with an average age of death of less than 20 years .

Calvert and al. found a median age of death of 18 and 18.5 years in 1993 and 1999, respectively, in the context of absence of ventilation. Very recently in 2011, Gordon et al. reported 60% survival at 24 years in the presence of corticosteroid and bisphosphonate treatment with a low ventilation rate.

The need for initiation of assisted ventilation and is now an evidence.

The moment of realization of the tracheotomy or the exclusive pursuit of NIV is however still under debate. Indeed, the breakdown in the first place most often is followed by NIV invasive tracheotomy most often because of an obstruction despite uncontrollable coughing assistance or due to major disturbances or difficulty swallowing to feed. It is a choice that must be made by the patient, if possible outside acute respiratory episod. The patient must understand the possibilities that are offered, complications of the different treatments or abstention.

In NIV, decluttering difficulties is the major drawback that can pose a threat to life person. The weakness of the expiratory muscles leads to inefficiency effect of cough and can be objectified by the “peakflow to cough (PFT)” .

When the flow is less than 270 L/minute, coughing becomes ineffective with a threshold of 160 mL/minute of complete ineffectiveness. Manual and instrumental assistance are indispensable in absence of tracheotomy. With tracheotomy, decluttering is possible with endotracheal aspirations.

In NIV when the PFT is less than 270 L/minute, instrumental assistance must be provided quickly in case of congestionor a tracheotomy is often needed quickly.

The larger leaks are sometimes complicated by conjunctivitis and tolerance masks is sometimes poor and can lead to real bedsores. The frequency of chronic rhinitis is also worth mentioning. Difficulties can exist in taking meals with the mouthpiece.

The use of tracheotomy depends of teams and countries with a general tendency to extend the non-invasive ventilation (NIV) necessarily associated with instrumental methods of decluttering like “cough assist”.

Which represents a patient safety, tracheotomy has many disadvantages including the frequency of respiratory infections, associated with increased progressive resistance of germs. It increases bronchial hypersecretion and tracheal lesions , sometimes responsible for bleeding (0.7%). Stenoses are present in 3 to 12% of cases and fistulas less than 1% . These complications of tracheotomy were found in the study (16.2% of causes of death) and this is confirmed by various studies .

Talk perturbance is absent except when it is necessary to set up a cuff (usually only inflated the night) necessary by excessive leaks or flooding continuous saliva.

The increasing dependence with necessity of a possible intervention 24 upon 24 is not just for the tracheotomized patients but also for whose with permanent NIV. However, the difficulty of finding a place suitable living is increased with tracheotomy. This one closes access to many centers or homes and forcing some of them to leave home.

Informal surveys conducted at the center as well as data from the literature have shown that ventilator assistance and also tracheotomy does not impair the quality of life for patients with DMD despite an important dependence in activities of daily life.

The current study did not aim to recommend either the continuation of the NAV or early tracheotomy.

The current trend of teams, more marked for some is to extend NIV . This trend was not found in the study with no increase in the age of tracheotomy over the years.

The age at completion of tracheotomy in the population studied was relatively early to 21.66 years and followed the NIV of only 3.48 years (SD ± 2.78 years). There was no change in the age at completion of the tracheotomy (that has not changed) over the years. The more systematic use of instrumental aids to decluttering and the generalization of the NIV daytime ventilation should result in an increase in the age of tracheotomy.

We have reviewed the median age of death and increase of survival in other centres were ventilatory assistance was systematically implemented and compared to our study.

Without ventilatory assistance, mean survival of DMD patients after onset of diurnal hypercapnia is 9.7 months.

This hypercapnia leads most of the time to the onset of ventilator assistance. In the current study, life expectancy after tracheotomy for the 77 DMD patients with tracheotomy was 17.17 years and so increased by more than 16 years.

In our study, the median survival (life expectancy) for the 76 DMD patients (with or without ventilatory support) born after 1970 was 40.95 years and 25.77 years for those born before 1970.

Simonds et al. found 85% and 73% survival at 1 and 5 years after onset of ventilatory assistance, respectively.

Kohler et al. published a study of 43 patients aged 5 to 35 years, and reported initiation of NIV at 19.8 years (SD ± 3.9). In this study , the probability of survival at 5 and 10 years after initiation of NIV was 82% and 68%, respectively, similar to 84.8% and 62.8% in our study. Moreover, the probability of survival in Kohler et al. was 80% at age 30, with a median survival of 35 years, very similar to that observed at the AFM centre (82.3% survival at age 32).

Bach et al. found a median survival of 30.6 years for DMD patients with ventilatory assistance only through NIV, and Toussaint et al. reported a median survival of 32.5 years in 41 DMD patients likewise treated by NIV.

Ishikawa et al. studied a population of 227 DMD patients from 1964 to 2010 and stratified their patients in three different groups, according to whether patients were without ventilatory assistance, with assistance through tracheotomy or NIV. Median survival was 18.1, 28.9 and 39.6 years, respectively.

Our results (mostly with tracheotomy) are similar to this results with NIV.

1.5.2

Causes of death

In our study, cause of death could be documented only for 37 of 55 DMD patients. Twenty-five of these patients (67.5%) died from respiratory-linked complications and 12 (32%) succumbed from cardiac-related disease isolated or associated related from 1990, most of the patients benefited of verntilatory assistance. So, before 1990, when cause of death could be documented, 92% of the causes of death were respiratory linked and cardiac linked for 8%.

This is also noted in the studies where no systematic ventilatory assistance was provided. Indeed, without ventilatory assistance, respiratory complications were causally linked to death in 90% of cases and only a small proportion of deaths was to cardiomyopathy (10%).

From 1990, causes of death radically changed. 52% of the patients died from respiratory (on diminution) linked cause and 44% from cardiac related cause (on augmentation).

Similar to our situation, Spurney noted an increase in the proportion of cardiac-related deaths (20% of total deaths) following implementation of respiratory care.

Bach et al. found a very high prevalence of cardiac-related (52% of total) deaths and a low prevalence of respiratory-linked deaths (21%) in DMD patients using NIV. Causes of death were unknown in 27% of cases.

1.6

Conclusion

Numerous publications have reported that ventilatory assistance significantly improves survival of DMD patients, as also experienced at the AFM Yolaine de Kepper centre over the past 30 years. The median survival age in these patients now reaches 40 with no impairment of quality of life. Ventilatory assistance must therefore be systematically proposed to all DMD patients.

We observed a significant increase in this 30 years of life expectancy through ventilation with tracheotomy performed fairly early.

Life expectancy after tracheotomy was more than 17 years. So ventilation by tracheotomy represents a safe and effective treatment but associated with the presence of numerous complications related to tracheotomy.

The timing of realization of tracheotomy (not too early but not too late) is crucial.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La dystrophie musculaire de Duchenne (DMD) est la plus fréquente des dystrophies musculaires. Elle se transmet sur le mode récessif lié au chromosome X et atteint un garçon sur 3500 à la naissance. L’atteinte est liée à l’absence d’une protéine particulière appelée dystrophine dans le myocyte, qui entraîne la perte de l’intégrité membranaire suivie par une destruction progressive de la fibre musculaire.

Les signes cliniques commencent à être visibles généralement entre les âges de deux et cinq ans avec apparition progressive de difficultés pour courir, monter les escaliers et la survenue de chutes. Une atteinte cognitive peut être présente dans 30 % des cas.

Progressivement, la faiblesse et la fonte musculaire qui prédominent à la ceinture pelvienne s’étendent aux autres muscles. Le signe de Gowers – les enfants utilisent leurs bras pour redresser leur tronc en déplaçant les mains le long des cuisses lorsqu’ils se relèvent de la position à genoux – est observé à un âge médian de cinq ans et la marche devient dandinante. Avec l’aggravation du déficit, les chutes deviennent de plus en plus fréquentes et le relevé du sol devient impossible. La marche autonome devient impossible le plus souvent entre neuf et 13 ans . Les rétractions s’aggravent aux niveaux des membres inférieurs et supérieurs. Une scoliose sévère survient qui nécessite souvent la réalisation d’une arthrodèse rachidienne.

Le déficit moteur se majore avec réduction de l’autonomie pour les actes simples de la vie journalière. S’alimenter seul devient impossible vers l’âge de 18 ans.

Avant que l’assistance ventilatoire par trachéotomie ou non invasive ne soit proposée, le décès survenait classiquement entre 16,2 et 19 ans, presque toujours avant l’âge de 25 ans , principalement par insuffisance respiratoire terminale, cause principale de décès.

En effet, la capacité vitale (CV) qui progresse normalement jusqu’à l’âge de neuf à dix ans ralentit après cet âge et décroit de 5 à 10 % par an après 14 ans et, en l’absence de ventilation assistée, le décès survient le plus souvent vers 18 ans .

L’hypercapnie résultant de l’hypoventilation survient dans un premier temps la nuit .

À cette période, la CV est habituellement entre 20 et 50 % de la CV théorique et la ventilation non invasive (VNI) n’a pas montré d’effet bénéfique sur la survie .

L’apparition d’une hypercapnie diurne suit cette période et sans assistance ventilatoire, l’espérance de vie est inférieure à un an .

Ainsi, dans la DMD, les critères de mise en route d’une ventilation sont suivant les équipes :

- •

soit (Raphael et al., 1994) : une CV inférieure à 20 %, une PaCO2 supérieure à 45 % ou deux poussées d’insuffisance respiratoire aiguë ;

- •

soit (Toussaint et al., 2008) : une CV inférieure à 680 mL et une pression maximale inspiratoire (MIP) inférieure à 3,5 kPa (prédictif d’hypercapnie diurne) .

Progressivement, le temps de ventilation est augmenté dans la journée, le plus souvent avec un embout buccal. La dépendance pour la ventilation est souvent permanente vers 23 ans lorsque la CV atteint 320 mL .

Une trachéotomie est proposée en cas de non-faisabilité ou de souhait du patient. Le plus souvent, celle-ci est réalisée en raison d’un encombrement incontrôlable malgré une assistance à la toux ou en raison de troubles majeurs de déglutition ou de difficultés pour s’alimenter.

L’atteinte cardiaque représente l’autre principale cause de décès. Il s’agit d’une cardiomyopathie dilatée qui débute parfois très tôt dès l’âge de cinq ans, devient symptomatique à 15 ans (diagnostic de cardiomyopathie effectué à 14,4 ans (± 2,3 ans) dans l’étude de Connuck et al. ) et quasi systématique après 18 ans. L’évolution de la myocardiopathie n’est pas corrélée avec l’importance de l’atteinte musculaire squelettique ou respiratoire. Les traitements de la myocardiopathie (inhibiteurs de l’enzyme de conversion associés éventuellement aux bêtabloquants) sont recommandés dès dix ans . Les corticoïdes ralentissent également l’évolution de la cardiomyopathie .

Le but de l’étude actuelle est de mesurer l’évolution de l’espérance de vie survenue dans les 30 dernières années au centre AFM Yolaine de Kepper (France) où des patients atteints de DMD ont séjourné depuis 1981 de façon temporaire ou permanente. La part de la prise en charge respiratoire qui a débuté dans certains centres à la fin des années 1970, mais de façon plus systématique entre 1985 et 1990 ainsi que les causes de décès ont été également étudiés.

2.2

Patients et méthodes

2.2.1

Patients

Tous les patients diagnostiqués DMD ayant séjourné au centre AFM Yolaine de Kepper, Saint-Georges-sur-Loire, France, entre 1981 et septembre 2011 ont été inclus dans cette étude rétrospective. Le patient inclus le plus jeune était né en mars 1955, le plus âgé en 1994.

Le centre AFM accepte uniquement les patients adultes (> 18 ans). Le centre AFM est actuellement une maison d’accueil spécialisé (MAS) qui accueille des résidents de façon permanente ainsi que des résidents temporaires pour des durées le plus souvent de un à trois mois. Le recrutement du centre pendant ces années a été national avec une prédominance régionale. Les décisions thérapeutiques notamment de ventilation assistée, trachéotomie ou gastrostomie ont été prises pour certains patients alors qu’ils résidaient au centre AFM. Les choix proposés par les médecins référents du CHU d’Angers (réanimateurs et pneumologues) ainsi que par les médecins du centre ont pu être validés par le patient lui-même ou par les personnes représentatives. Pour les résidents temporaires, les décisions ont été prises dans d’autres centres sauf lorsqu’une décompensation respiratoire est survenue lors de leur séjour.

Parmi les 131 patients nés entre 1955 et 1994 ayant un diagnostic de DMD qui ont séjourné au centre, 36 avaient un diagnostic confirmé (biopsie confirmant l’absence de dystrophine et/ou diagnostic génétique). La certitude du diagnostic étant impossible avant 1987, de nombreux patients n’avaient pas initialement de diagnostic confirmé. En l’absence de cette confirmation diagnostique, les critères antérieurs à 1987 ont été retenus pour distinguer la DMD d’autres dystrophies musculaires et en particulier de la dystrophie de Becker qui est une forme moins grave de dystrophinopathie.

Ces critères étaient le mode de transmission, l’histoire clinique et paraclinique compatible avec celui de DMD (biopsie, EMG, CPK, date du début des troubles, âge de perte de la marche autonome ne dépassant pas 13 ans, nécessité d’une ventilation assistée au plus tard à 26 ans ou décès avant cette date si non ventilé). Quatre-vingt-trois patients répondants à tous les critères ci-dessus ont été inclus et considérés comme des patients atteints de DMD probables.

Douze patients nés entre 1951 et 1972 n’ont pas été retenus car ne répondaient pas à au moins un des critères notamment l’âge de perte de la marche, la nécessité d’une ventilation assistée après 26 ans ou l’absence de renseignements suffisants.

Aucun des 119 patients de l’étude n’a bénéficié antérieurement de traitement corticoïde actuellement considéré comme recommandé .

2.2.2

Analyse statistique

Les courbes de survie ont été obtenues par la méthode de Kaplan-Meier.

La comparaison des courbes de survie a été réalisée par le Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) Test ainsi que par le Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test.

2.3

Résultats

2.3.1

Population

Au 15 septembre 2011, 55 patients étaient décédés, 36 en vie et 28 perdus de vue.

2.3.2

Augmentation de l’espérance de vie pour les patients patients nés après 1970

L’année 1970 a été choisie comme un seuil car la ventilation assistée a été plus systématique entre 1985 et 1990 et proposé aux patients atteints de DMD ayant un âge entre 15 et 20 ans.

La médiane de survie (espérance de vie) pour les 76 patients atteints de DMD (avec ou sans assistance ventilatoire) nés à partir de 1970 est de 40,95 ans et de 25,77 ans pour ceux nés avant 1970 ( Fig. 1 ).