Evaluation, Clinical Decision Making, and Nonoperative Management of Recurrent and Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears

Ofer Levy

Ehud Atoun

Alexander Van Tongel

INTRODUCTION

Rotator cuff (RC) tears are among the most common conditions affecting the shoulder.

An illustration of a rent in the supraspinatus tendon by A. Monro secundus in 1788 in a book called A Description of All the Bursal Mucosae of the Human Body appears to be the first picture of a torn RC.12,61 The first detailed description of a series of traumatic RC tears appeared in the London Medical Gazette in 1834 and is attributed to J.G. Smith, who described the occurrence of tendon rupture of the shoulder following injury.76 The first description of degenerative RC tears was given in 1853 by Robert W. Smith, who reviewed in detail a case of superior migration of the humerus and absent cuff tendons that he ascribed to a long-standing rheumatic condition of the shoulder.12 He was critical of John G. Smith, the Hunterian scholar, for ascribing such changes to trauma.12

Concerning operative treatment, in 1886, Bardenheuer noted that tears of the RC tendons were reparable and should be reattached with suture.12

In 1911, Codman, one of the pioneers in the research of RC pathology, described his first repair but he could not fully cover the humeral head with the repair.16 The gap left bridged by suture was referred to as a “suture a distance.” To our knowledge, this is the first description of a surgical irreparable RC tear.

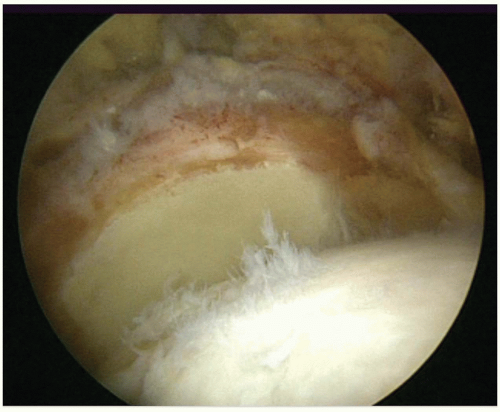

Codman described relatively good outcome and good function in the two patients, although only partial RC repair was achieved.16 Irreparable RC tears present a complex and difficult challenge for the shoulder surgeon. Irreparable RC tears are lesions consisting of massive RC tears that are not reparable by conventional means (Fig. 2-1). There is no consensus regarding the definition of an irreparable RC tear and although the reparability of the tear is largely dependent on the size and chronicity of the tear, it is still surgeon specific, depending as well on the experience and skills of the surgeon.

Even when an RC tear has been repaired, there is a high rate of nonhealing of the tear or re-tears. The average percentage of re-tears in some series varies from 18.6% to 54% for open or arthroscopic RC repair.7,14,26,27 and 28,41,45,46,49,53,54,56,78,86 There are multiple factors that influence the ability of an RC tear to heal. These factors can be divided into tear, patient, and surgeon factors. Tear factors include size and retraction of the tear, chronicity of the tear, tissue elasticity and tissue quality, muscle atrophy, and fatty infiltration.

Patient factors include patient’s age and gender, delay in surgery, smoking, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and co-morbidities, especially, diabetes mellitus.

Surgeon factors are the techniques used and the surgeon’s experience and skills.

In the first part of this chapter, we discuss the diagnosis and evaluation of these pathologies and suggest a clinical decision algorithm for the reparability of RC tear. In the second part of this chapter, we describe the nonoperative modes for the treatment for irreparable and recurrent RC tears.

DEFINITIONS

Massive Rotator Cuff Tear

There is no consensus regarding the definition of a massive RC tear. Both anatomic and functional characteristics have been used to classify RC tears, but each methodology has limitations.

FIGURE 2-1. Arthroscopic view (from the lateral portal of a right shoulder) of massive irreparable rotator cuff tear, retracted beyond the glenoid. This is a posterosuperior tear. |

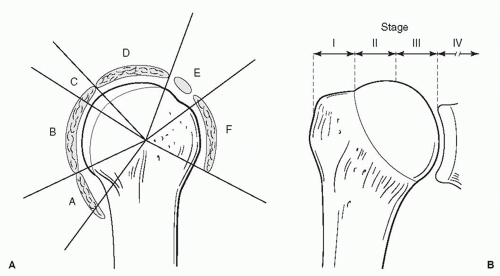

Various classification systems have been used to define a “massive” tear (Fig. 2-1). Cofield et al. defined massive tears as those whose anterior-posterior dimension exceeds 5 cm,17,18 while Patte classified RC tear according to the topography, the number of involved tendons, and the amount of tendon retraction71 (Fig. 2-2A,B). Nobuhara et al. defined the size of the tear by estimating the amount of exposed humeral head.63 Zumstein et al. defined a tear as massive if there was complete detachment of two or more tendons.98 Burkhart proposed a classification of RC tears based on the tear pattern and the mobility of the tear margins.10

Massive tears can be further classified by chronicity and are defined as acute, acute-on-chronic, or chronic. An acute tear occurs after a traumatic event. An acute traumatic tear is usually flexible and easier to repair. If a large acute traumatic tear is neglected, the patient may develop severe retraction of the tendon and muscle atrophy together with shoulder stiffness that will make late repair very difficult with unpredictable result.

Patients with an acute-on-chronic RC tear are usually older and present with either new-onset or acutely deteriorating shoulder pain with underlying cuff pathology or acute deterioration of shoulder function after a traumatic event. Chronic massive tears are usually found in elderly patients with varying degrees of pain and functional deficit.

RC tears can also be described by the location of the tear. Most massive tears appear to follow two distinct anatomic patterns of posterosuperior or anterosuperior tears. Tears that involve the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus, with or without the teres minor tendon, are considered as posterosuperior tears. An anterosuperior tear involves a complete tear of the supraspinatus and the subscapularis tendons. These tears may be associated with instability or rupture of the proximal biceps tendon. Massive irreparable tear can involve all the RC tendons and be classified as “bald head.” All the anatomic patterns often result in severe disability and poor function. Loss of the coracoacromial arch combined with anterosuperior instability may lead to escape of the humeral head, a potentially devastating clinical situation.

Prevalence of Massive Tears

The prevalence of massive tears reported in the literature has ranged from 10% to 40% of all RC tears.23,24

Harryman et al. reported that 28% (53) of all (191) surgically repaired RC tears in a 5-year period were massive posterosuperior tears.40,41 Massive anterosuperior tear configurations involving the supraspinatus and subscapularis tendons are less common, ranging from approximately 5% to 20% of all RC tear patterns.40,41,47,93 It is critical to recognize that massive RC tears are not necessarily synonymous with irreparable tears. While the repair of massive tears can often be technically challenging, many are reparable.57 An acute traumatic tear or an avulsion injury may be >5 cm in dimension but have a good-quality elastic tendon stump and be anatomically reducible without placing excessive tension on the repair.

Definition of Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears

Irreparable RC tears are lesions generally consisting of large to massive RC tears that are not reparable by primary means: tendon to bone. The true incidence of irreparable RC tears is not known. Rockwood and others18,74,93 defined irreparable tears as those that, because of their size and retraction, cannot be repaired primarily due to their insertion onto the tuberosities despite conventional techniques of mobilization and soft-tissue releases. The reparability of a tear is dependent on multiple factors such as the size of the tear, its configuration, the number of tendons involved, the tear retraction and adhesions, the tear chronicity, and the tissue elasticity. The healing potential of a repaired tear is further dependent on the tendon tissue quality and RC muscle fatty atrophy and infiltration, the patient age, smoking, and co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus.

Although the reparability of the tear is largely dependent on the size and chronicity of the tear, it is still surgeon specific, depending as well on the experience and skills of the surgeon.

Massive irreparable RC tears occur in two physiologically distinct patient groups, but they can present in all age and activity groups. Most often, these tears occur in physiologically older, lower demand patients who have been asymptomatic until minor trauma created symptoms or had a gradual deterioration of pain and function without a traumatic event. The second group consists of physiologically younger, more active patients, often in the fifth or sixth decade of life, who present with dramatic symptoms of pain and disability after an acute event or with a history of RC surgery or of chronic RC injury.

Despite improvement in the understanding of RC pathology, advances in surgical treatment and instrumentation, and improvement in biomechanical repair techniques, there is a rather high rate of nonhealing of the tears or recurrent tears. The average percentage of re-tears in some series varies from 18.6% to 54% for open or arthroscopic RC rep air.7,14,26,27 and 28,41,45,46,49,53,54,56,78,86 Tear size was found to correlate with recurrence and functional deterioration in both open and arthroscopic repairs.53

The finding of incomplete structural integrity of the RC tear does not necessarily mean a clinical failure.53

What are the definitions of a failure of RC repair? Failure can be defined by each of the following: as continued pain, limited function with painful movements, stiffness or loss of movement and pseudoparalysis with severe limitations in performing even simple activities of daily living, or any combination of the above.

Biomechanics of Massive Cuff Tears

The deltoid and RC muscles work synergistically to maintain a balanced force couple for the glenohumeral joint in both the coronal and transverse planes. The deltoid and RC inferior to the humeral head equator maintain a balanced coronal force couple, while the subscapularis and infraspinatus/teres minor complex balance each other in the transverse plane. In this capacity, the RC muscles function as primary dynamic stabilizers to maintain a concentric reduction during rotation of the humeral head on the glenoid.1,10,11,70,77,83 Massive cuff tears can disrupt this force couple and ultimately compromise the fulcrum that is necessary for normal glenohumeral mechanics. A shoulder with massive RC tear that maintains its ability to actively elevate the arm above the horizontal is therefore a “compensated or balanced” shoulder that retains a good anterior and posterior force couple that enables the deltoid to elevate the arm above the horizontal.

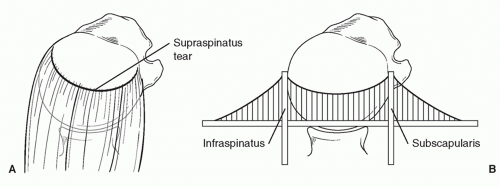

Burkhart11 radiographically evaluated 12 shoulders with massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears and described 3 patterns of glenohumeral kinematics: stable, unstable, and captured fulcrum. Burkhart found that the force coupling about the joint could be maintained in patients with isolated tears of the supraspinatus, and the shoulder function was relatively preserved. However, if the tear extended into the anterior (i.e., subscapularis involvement) or posterior (i.e., posterior infraspinatus or teres minor damage) cuff tendons, the force coupling about the joint was disturbed and led to unstable kinematics and loss of function. Therefore, Burkhart proposed a “suspension bridge” concept of RC tendon tears (Fig. 2-3) and argued that function can be maintained, even in the presence of a large tear, if the force coupling about the joint can be preserved.10

When the tear also compromises the inferior half of the RC, however, the balanced force couple in the coronal plane is lost and the patient will not be able to actively elevate the arm above the horizontal.1,10,11,70,77,83

Using a cadaver shoulder model, Hansen et al. demonstrated that stable glenohumeral abduction without excessive superior humeral head translation could be maintained in the setting of a massive tear but requires the generation of higher forces in the deltoid and the remaining intact portion of the RC.39 Subscapularis forces increased from 30% to 85% depending on the tear size. Some individuals with a massive tear, even those with a tear that involves the inferior infraspinatus and teres minor tendons, can maintain active shoulder abduction and good function with low-demand daily activities.39

HISTORY, PHYSICAL EXAMINATION, AND IMAGING

Patients with massive or irreparable RC tears can present with a variety of manifestations. They may have no symptoms or mild symptoms, or they may be completely disabled and in severe pain.

Symptomatic massive RC tears are frequently painful, particularly at night and during activities of daily living. Patients may report varying degrees of weakness and varying losses of range of motion, ranging from little or no deficit to a complete loss of active motion (pseudoparalysis) (Figs. 2-4). Patients with chronic weakness may also develop limitation of passive motion due to soft tissue contractures and scar tissues around the joint.

On physical examination, patients with a long-standing tear may have visible atrophy of the supraspinatus and/or infraspinatus muscles (Fig. 2-5). Swelling can be seen in cases of subdeltoid effusion due to free passage of synovial fluid between the glenohumeral joint and subacromial bursa in massive tears (Fig. 2-6). Codman described this swelling of the subdeltoid bursa and called it “Vorwolbung” (German for “bulge”) of the subdeltoid bursa.

Most patients with large tears are likely to demonstrate weakness of the supraspinatus strength and the examiner should carefully assess involvement of the remaining tendons. External rotation weakness is characteristic of massive RC tear. Elevation weakness is a less consistent finding. Some patients have sufficient deltoid strength to mask the absence of supraspinatus strength. The Jobe empty can test, which assesses strength with the shoulder elevated approximately 90 degrees and internally rotated with the thumb pointing downward, usually will cause pain and elicit weakness. Pain also can be the cause of inability to elevate the arm. Depending on the

location and extent of the tear, weakness may be seen also in the anterior (subscapularis) and/or posterior (infraspinatus and teres minor) cuff.

location and extent of the tear, weakness may be seen also in the anterior (subscapularis) and/or posterior (infraspinatus and teres minor) cuff.

Functional deficits often correlate with the location of the tear. Posterosuperior cuff disruption typically causes decreases in abduction, forward flexion, and active external rotation.6 Patients may have weakness in external rotation and a positive external rotation lag sign, which is the inability to hold one’s arm in a position of maximum external rotation (Fig. 2-7A,B). Patients with a larger tear, with complete loss of external rotation strength, may exhibit a positive hornblower’s sign (they are unable to externally rotate the shoulder and when asked to reach for their mouth, in order to achieve that, they will fully abduct the arm to overcome the loss of active external rotation) (Fig. 2-8).6,28,98 Walch et al. found this sign to be 100% sensitive and 93% specific in terms of identifying irreparable tears of the teres minor with grade 3 and 4 Goutallier fatty degeneration.6,28,65,91,98

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree