Evaluation and Management of Clavicle Malunions and Nonunions

David Ring

Jesse B. Jupiter

INTRODUCTION

Neer and Rowe both estimated that less than 1% of nonoperatively treated diaphyseal clavicle fractures failed to heal.29,36 Now it is clear that displaced and comminuted fractures have a nonunion rate of approximately 10% to 15% with nonoperative treatment.39 Both the mobility at the fracture site and the deformity of the bone and shoulder girdle can cause symptoms and dysfunction,10,25 but the fact that clavicle nonunion was underdiagnosed in the past suggests that many patients adapt well. For patients with malunion and nonunion who are unsatisfied with their situation, operative treatment can gain union, improve alignment, and decrease impairment and disability of the shoulder.

ANATOMY AND FUNCTION

The clavicle holds the glenohumeral joint and the upper extremity away from the trunk in all positions. The clavicle enhances overhead activity (combination of shoulder abduction and elevation), particularly in actions requiring power and stability, and resists those tensile forces that become so prominent in activities required by arboreal mammals. The clavicle also serves as a bony framework for muscular attachments, provides protection for the underlying neurovascular structures, transmits the forces of accessory muscles of respiration (e.g., the sternocleidomastoid) to the upper thorax, and contributes to the aesthetics of the base of the neck.22,27

Limitations of overhead activities requiring strength, stability, and dexterity have been noted in patients with cleidocranial dysostosis.23 If these congenitally aclavicular children have notable functional deficiencies in comparison with normal children, then it is logical that the learned coordinated manipulation of the complex interaction of various muscle groups, ligamentous attachments, and interarticulations of the shoulder girdle is disrupted by sacrificing clavicular continuity in adult patients.

Because some reports document good function following total or subtotal resection of the clavicle for infection, malignancy, or access to neurovascular structures in small series of patients,9,11 some authors went so far as to encourage consideration of the clavicle as an expendable or surplus part of the skeleton.16 Resection of the clavicle has been recommended both in the treatment of clavicular nonunion and in the treatment of fresh clavicular fractures.31

It is certainly clear that some patients do very poorly following clavicular resection, especially those with trapezial paralysis.37 We therefore feel strongly that this procedure should be reserved for the unusual situation in which a salvage procedure becomes necessary. The clavicle plays an important functional role in the shoulder girdle, and every effort should be made to preserve or restore normal length and alignment in the treatment of clavicular disorders.

PRESENTATION

Patients typically report pain (often experienced as weakness) and crepitation with shoulder motion. The deformity of the clavicle is usually obvious, and there is sometimes winging of the scapula related to the malalignment of the shoulder girdle.

The most common deformity includes medial—lateral shortening, drooping, adduction, and protraction of the shoulder girdle. The forces contributing to persistence or worsening

of deformity following fracture include the weight of the shoulder as transmitted to the distal fragment of the clavicle primarily through the coracoclavicular ligaments as well as the deforming forces of the attached muscles and ligaments.

of deformity following fracture include the weight of the shoulder as transmitted to the distal fragment of the clavicle primarily through the coracoclavicular ligaments as well as the deforming forces of the attached muscles and ligaments.

Symptoms consistent with thoracic outlet syndrome or even brachial plexus palsy may develop weeks or years following injury, due to hypertrophic callus and/or malalignment of the fracture fragments leading to compromise of the costoclavicular space.13,18 Narrowing of the costoclavicular space due to malunion or nonunion can also lead to a dynamic symptomatic narrowing of the thoracic outlet.2,3

RADIOLOGICAL EVALUATION

An anteroposterior view in the coronal plane of the clavicle will identify and localize the majority of clavicular fractures. Quesada recommended 45-degree caudad and cephalad views, which he felt would facilitate evaluation by providing orthogonal views.34

The abduction-lordotic view, taken with the shoulder abducted above 135 degrees and the central ray angled 25-degree cephalad, proves useful in evaluating the clavicle following internal fixation.35 The abduction of the shoulder results in rotation of the clavicle on its longitudinal axis at the sternoclavicular joint, causing the plate to rotate superiorly and thereby exposing the shaft of the clavicle and the fracture site under the plate. A standing chest radiograph that includes both clavicles may provide information regarding shortening of the involved clavicle.

Computed tomography is often used to assess union and alignment of the clavicle, but the diagnostic performance characteristics and interobserver reliability of CT for these diagnoses have not—to our knowledge—been studied.

INDICATIONS

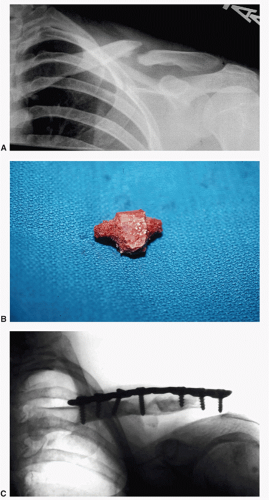

Operative treatment for nonunion and malunion is offered to patients with symptoms and disability that correspond with impairment and pathophysiology (deformity and nonunion); that are healthy, reliable, and have realistic expectations; and that understand the risks, benefits, discomforts, inconveniences, and alternatives to surgery. Active infection is first debrided to vital tissue and treated with parenteral antibiotics. Thin, inadequate skin cover is addressed either before or during the surgery. A few nonunions are hypertrophic, but the vast majority are atrophic and bone graft is often required to maintain length (Fig. 27-1A). We have not found vascularized bone grafts (e.g., fibular or medial femoral condyle) necessary in the clavicle, but there may be occasions for the use of these techniques.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUES

An incision is made in line with the clavicle and inferior to it. This limits risk to the larger branches of the supraclavicular nerve and ensures that the incision does not lie directly over the plate.

The platysma is split with a combination of blunt and sharp dissection in line with the wound. We look for and try to protect the supraclavicular nerves to limit the potential for neuroma formation, but we understand that not all surgeons do this.

We expose the superior surface of the clavicle without elevating periosteum or muscle. If we plan to use an anterior plate, we elevate the pectoralis major and deltoid origins from the shaft extraperiosteally. We are aware that some surgeons perform a subperiosteal exposure. A superior plate may help convert the downward force on the distal clavicle into compression forces across the clavicle. An anterior plate may be less prominent, have longer screws distally where the clavicle become thin but wide, and may resist axial pull out of the screws from the lateral part of the plate which can happen with a superiorly placed plate6,8,19 (Fig. 27-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree