De Korvin Georges

CHP Saint-Grégoire, 35768 Rennes, France

Delegate of France

President of the Clinical Affairs Committee, UEMS PRM Section

Quittan Michael

Kaiser Franz Joseph Hospital, Vienna, Austria

Delegate of Austria

Rapporteur of the Clinical Affairs Committee, UEMS PRM Section

Juocevicius Alvydas

Vilnius University Hospital Santariskiu Klinikos, Vilnius, Lithuania

Delegate of Lithuania

Member of the Clinical Affairs Committee

Lejeune Thierry

Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, UCL, Brussels, Belgium

Delegate of Belgium

Member of the Clinical Affairs Committee

Lains Jorge

Hospital Rovisco Pais, Tocha, Portugal

Delegate of Portugal

Member of the Clinical Affairs Committee

McElligott Jacinta

National Rehabilitation Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

Delegate of Ireland

Member of the Clinical Affairs Committee

Mikova Vladislava

Hospital Tabor, Czech Republic

Delegate of the Czech Republic

Member of the Clinical Affairs Committee

Nollet Frans

Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Delegate of The Netherlands

Member of the Clinical Affairs Committee

Delarque Alain

Université de la Méditerranée, CHU La Timone, 13385 Marseille, France

Delegate of France

President of the Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine Section of the European Union of Medical Specialists

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Delegates from 31 countries participate in the activities of the section and board of the Union of european medical specialists ( Union européenne des médecins spécialistes [UEMS]) . Twice a year, these delegates hold a three-day General assembly, where they work on three different committees:

- •

the Education committee, also called the European board;

- •

the Professional practice committee, which addresses PRM fields of competency;

- •

the Clinical affairs committee (CAC), which focuses on PRM quality of care.

From 2001 to 2004, under the presidency of Professor Bengt Sjölund, the Clinical affairs committee pondered the ethical foundations and the research perspectives pertaining to quality of care and finally chose a concrete pragmatic approach. Thus, in 2004, the Committee decided to adopt the PRM programme of Care (PRM-PC) as a basis for their work and to set up a European PRM-PC accreditation based on a user-friendly and easy-to-manage system.

To accomplish this, an online questionnaire was put up on a dedicated website so that PRM Specialists could submit their programmes to a five-member European jury. During the pilot phase (2006 to 2008), 13 PRM-PCs were accredited through this procedure. This pilot phase proved the feasibility of such a project, but it also raised many questions, for example, about:

- •

the interaction between jury members and applicants;

- •

the relationship between scientific foundations based on international and national publications/recommendations and clinical practice;

- •

the advantages of participating in such a European accreditation system.

In early 2009, this European approach to PRM-PC also led the French PRM union (SYFMER) to bring the PRM-PC concept into negotiations of funding for functional assessment tools, such as isokinetic dynamometry and surface topography. The National health insurance (UNCAM) reacted fairly positively, and this positive reaction further advanced the European PRM-PC accreditation system, while at the same time influencing some of its procedures.

As a result, an upgraded version of the accreditation procedure was set up in March 2009 after the general assembly in Cambridge (England). The new version is now available on the website www.euro-prm.org . Whereas the first questionnaire focused mainly on organizational aspects, the new accreditation template focuses more on a given programme’s background data and fundamental issues, along with the structured content elaborated by the PRM Specialist in response to patient needs. UEMS hopes that this European accreditation system will become a PRM-PC laboratory, in which applicants will be helped to express their clinical expertise in the most valuable, beneficial way for the patient and for other PRM specialists.

This paper traces the steps and the deliberations that led to the current system, which is then explained in detail. It concludes with recommendations to facilitate the participation of any PRM Specialist who applies for European accreditation of a PRM programme of care. In turn, this facilitated participation is expected to make the PRM specialty more visible and comprehensible throughout Europe, in the interests of the patients.

1.2

Aims and goals

Achieving the best possible quality of care is an ethical obligation for any physician. However, beyond the personal commitment, some pioneers – for example, the Mayo brothers, whose standards still remain up to date – started formalizing this quality approach many years ago. In 1997, the Council of Europe followed through, issuing Recommendation No. R(97)17 about the legal proviso to develop and implement quality improvement systems (QIS) in health care .

UEMS started to address this issue very early and, in 1996, adopted an initial European charter for quality assurance in a specialized medical practice . More recently, UEMS issued three consensus documents about quality of care:

- •

the Basel declaration (2001) , which is about continuing professional development;

- •

UEMS policy statement on promoting good medical care (2004) , which defines quality assurance as a continuing review process rather than predefined standards of care;

- •

the Budapest declaration on ensuring the quality of medical care (2006) , which defines de UEMS policy about medical rules: any control system should take into account the context of the medical practice, the societal expectations and the available resources for providing medical care.

UEMS asked the following questions:

- •

how should quality of care be promoted in a fast-moving European landscape, with the arrival of new countries in the European community (EC)?

- •

how should a heterogeneous and poorly-known situation be taken into account, without being biased by North-South or West-East prejudices?

- •

how should quality of care be addressed in a specialty that cannot be defined by a single anatomical territory or by a unique technology, but rather is based on a philosophical consensus shared around the world?

In addition to these conceptual questions, UEMS considered it essential to generate “raw data” from daily clinical practice, without trying to impose an a priori evaluation framework imported from any one country, nor any predefined scale of values.

From this perspective, the concept of PRM programme of care (PRM-PC) appeared to be the best foundation for developing a European approach to quality of care. UEMS wanted the PRM-PC concept to become the most appropriate response to the population’s needs. PRM Specialists, who are the people responsible for a PRM-PC, must describe the programme, covering the following programme elements:

- •

fundamental concerns – pathological and impairment considerations, disability and handicap issues, social and economic consequences, programme principles;

- •

objectives – target population, programme goals and targets in terms of ICF ;

- •

contents – assessment (diagnosis, impairment, activity and participation, environmental factors), intervention (programme timeframe, PRM specialist interventions, team interventions), follow-up and results (discharge plans, long-term follow-up);

- •

environment and organisation – clinical setting, clinical programme, clinical approach, facility; safety, patient rights, advocacy; role of the PRM specialists in the programme, team management procedures;

- •

information management – patient records, information management system, programme monitoring and results;

- •

quality improvements – identification of the programme’s strong and weak points, action plan to improve programme quality;

- •

references – scientific references and guidelines cited in the above description, details about national documents.

In Europe, the mandatory certification and accreditation procedures are focused either on the physicians or on the facilities. In France, facility accreditation includes special features that are appropriate for post-acute settings, in which PRM is included. However, UEMS-PRM/CAC hasn’t found any accreditation system specifically dedicated to PRM.

Under Professor Bengt Sjölund’s presidency, the CAC looked at experiences in North America, where programmes of care have existed for a long time. As early as the 2nd International congress of health accreditation (Marseille, France; 2000), Professor Yves-Louis Boulanger explained how PRM-PC had been developed in Montreal and Christine Mac Donnell described the accreditation system managed by Commission on accreditation of rehabilitation facilities (CARF) .

Nevertheless, these North American accreditation procedures were integrated into healthcare insurance systems that were much different from the various European systems for financing healthcare. These procedures could hardly be extended in their totality to a group of countries that, despite their very diverse cultural and legal frameworks, already put a heavy administrative burden on physicians.

Since the motivation behind European accreditation cannot be legal obligations or an immediate financial benefit, UEMS/CAC conceived a much lighter procedure that doesn’t require a lot of time and money. This procedure has two purposes:

- •

to better inform all kinds of people, from patients to decision-makers, about the high-quality services offered by the PRM specialty;

- •

to start a dynamic process for continually improving PRM quality.

These two purposes should be achieved without value judgements, rather seeking to highlight the value of existing clinical practices in every European country.

UEMS also thought that it was important to set up an accreditation system managed by PRM Specialists themselves, before any other entity tried to impose a system over which PRM Specialists had no control (e.g., conception, organisation, management, data produced).

1.3

Method: the pilot phase

In September 2004, the Dublin general assembly (GA) of the UEMS PRM section decided to set up a European accreditation system for PRM programmes of care. In February 2005, the Hanover GA approved the specifications elaborated by the Clinical affairs committee, and in September 2005, UEMS was able to present at the Limassol GA the first tentative model of this system, which was later upgraded several times.

The principle of this system was to let applicants fill out an online questionnaire, with a brief description of the care programme and a self-evaluation of its principal targets, objectives and organisation. This questionnaire will be described in detail later, along with the final version of the system.

Each candidate programme of care was submitted to five-member European jury to obtain an evaluation of the programme. The software on the website had been designed to allow automatic voting and to store the comments of the five jury members. The first real test phase began in 2006. Soon after the test phase began, it appeared that an information exchange between the Jury and the applicants would be essential for the correct interpretation of the binary responses (yes or no) on the questionnaire. This information exchange would work to improve the programme description. Therefore, in the 2007 upgrade of the accreditation website, UEMS added a dialogue space reserved for the jury and a zone for anonymous exchanges between the candidate and the jury.

1.4

Results

During the two-year pilot phase, 13 programmes were accredited ( Appendix A ). Candidate programmes were submitted from Austria (two programmes), France (two), Hungary (three), Italy (one), Lithuania (two) and Slovenia (three), which correspond to a fascinating East-West distribution and demonstrates the commitment of the newly admitted European countries to our approach.

When applying for programme accreditation, applicants could either choose a title from the suggestions in a pop-up menu or create an original programme title. Six titles were related to PRM applied to nervous system impairments, including three targeting stroke patients and one targeting patients with spinal cord injuries. Two programme titles were general (“General PRM Programme”), one of them specifically targeting children. The five other programme titles were:

- •

assessment and treatment of people with gait disorders;

- •

post-traumatic geriatric rehabilitation;

- •

amputee rehabilitation;

- •

PRM and patients with osteoporosis;

- •

rehabilitation of cancer patients.

This variety shows the importance of the neurological rehabilitation but also the wide scope of PRM application domains in different European countries. The two “General PRM” programmes prove that it is not necessary to be part of “super specialized” facility to submit a PRM-PC for European PRM accreditation by UEMS.

The website recorded several incomplete submissions, which were probably trial runs. But every programme that was conscientiously presented was accredited after the applicants provided additional information and made corrections to their questionnaires as requested by the jury.

As the pilot phase progressed, a series of 12 programme assessment criteria emerged from the jury’s debates, which were consensual most of the time:

- •

clearly described programme goals, expressed in the terms of the ICF;

- •

clear scientific basis for the programme (i.e., evidence-based medicine);

- •

clearly defined admission and discharge criteria;

- •

a reasonable number of patients per year;

- •

appropriate human resources, both in competency and number;

- •

continuing professional development for PRM Specialists and other team members;

- •

PRM specialist interventions are an integral part of the programme;

- •

the PRM Specialist plays an active role in the rehabilitation programme and does not only deal with comorbidity;

- •

patients rights are properly addressed;

- •

safety issues are properly addressed;

- •

patients records are properly managed and include rehabilitation data;

- •

programme outcomes are monitored and a quality assurance system is set up.

Professor Alvydas Juocevicius and his team performed a global analysis of the responses collected from the programmes accredited. The rate of positive responses to the various questions was generally high. A score of 100% was observed for three items:

- •

the PRM specialist intervention is an integral part of the programme;

- •

the PRM Specialist plays an active role in the programme;

- •

patients records are properly managed and include rehabilitation data.

The answer to the two first questions, about the PRM Specialist participation in the programme, may appear obvious in some countries, for example in France. However, this is not the case in certain countries, where a rehabilitation programme can be managed by a person who isn’t a physician (e.g., a nurse, a physiotherapist or any other “reference person”), while the physician’s role is limited to dealing with comorbidity. In fact, some items on the questionnaire were designed to be “educational”. The lowest scores were observed on two questions:

- •

50% for a clear link to evidence-based medicine (EBM);

- •

57% for clearly defined admission and discharge criteria.

The questionnaire ended with three questions designed to initiate a quality assurance approach:

- •

what are the most positive points of your programme?;

- •

what are the weakest points of your programme?

- •

what action plan do you intend to implement for improving your programme?.

The strong points mentioned by the applicants covered two complementary aspects:

- •

the services offered directly to the patient: comprehensive, personalized PRM care (6/13), comprehensive assessment before assignment to an outpatient or community-based rehabilitation service (2/13), good therapeutic efficiency (3/13), and a good cooperation with the patient’s relatives (1/13);

- •

the organization of the programme (which obviously also benefits the patients): a multidisciplinary team (9/13), an interdisciplinary approach (5/13), the proposal of research and educational programmes related to daily clinical practice (3/13), cooperative team management (e.g., with a foreign partner) (1/14).

The weak points mentioned by the applicants covered the following aspects:

- •

insufficient means allocated to the programme: lack of beds for early rehabilitation of amputees and cancer patients (2/13), insufficient human resources (e.g., neuropsychologist, speech therapist, occupational therapist) (3/13);

- •

gaps in the care programme: cognitive rehabilitation (3/13), occupational therapy and vocational rehabilitation (6/13);

- •

insufficient evaluation of the programme results.

The action plans for improving the programme focused on two issues:

- •

the means allocated to the programme (external factors, which cannot be controlled by the programme): more beds for inpatients or places in ambulatory care (2/13), more specialists (2/13), creation of a vocational rehabilitation department (1/13), improving the equipment (based on funding resources) (1/13), implementation of a software system (3/13);

- •

the organization itself (internal factors, which are more directly under the control of the programme director): updating existing procedures and defining new ones within a General PRM programme (1/13), improving cognitive rehabilitation for stroke patients (1/13), implementing ICF (2/14), continuing team education (1/13), improving programme monitoring (3/13).

1.5

Discussion: from the pilot phase to the final system

The pilot phase of our European accreditation system for PRM programmes of care was presented in several PRM congresses: the SOFMER Congress in Saint-Malo (2007) and in Mulhouse (2008), the European PRM Congress in Bruges (2008), the SIMFER Congress in Rome (2008) and the Baltic Congress in Riga (2008).

The discussions with congress participants, the debates within the UEMS section and board, and the exchanges between candidates and jury convinced UEMS-PRM Section of the usefulness of our approach, but also highlighted some of its weaknesses, which led us to propose improvements. Appendix B gives the new model for presenting a programme.

1.5.1

Strong and weak points highlighted by the pilot phase

The strong point is that our system gives structured information about European PRM programmes, whatever are their scopes, their means or their organisational type. Therefore, the European PRM accreditation system is a fantastic tool to obtain and distribute knowledge about the richness of PRM and the multiple ways that this specialty is adapted in actual daily practice.

The weak point is the jury’s difficulty to comprehend the essential nature of the candidate programmes. This is why the jury raised so many questions about the relevance of the responses to some of the questions in the questionnaire, which were intended to describe the programme. Several times, the programme scope was too wide to make some questions applicable. On the other hand, even though the open programme description had been allotted a full text window in the questionnaire, this description often proved to be too concise to represent the programme content accurately.

For instance, during the pilot phrase, our questionnaire clearly gave insufficient space for the programme content itself and for the detailed description of the PRM Specialist’s role within the programme. Indeed, other existing accreditation systems, which could be taken as examples, are not medically driven; consequently, they are naturally focused on the organizational aspects rather than on medical issues, which their managers cannot handle and control.

1.5.2

Information generated by the programme of care concept

Our recent talks with the French Health Insurance managers have taught us the importance being able to provide quantitative data about:

- •

the preprogramme stages (e.g., epidemiological, social and economic data);

- •

the operational stages (e.g., participation rate, length of treatment, quantification of all the means implemented by the programme, including those related to external prescriptions);

- •

the post-programme stages, including the assessment of not only the programme outcomes, but also the difference between the existence and non-existence of such a programme (e.g., in terms of the impact on external prescriptions, sick leave, medical nomadism).

Therefore, it is easy to imagine the richness of all the information that can be collected from the PRM-PC description. Of course, it would be impossible for a single team, even highly reinforced, to cover all the aspects mentioned above at the same time. Pragmatically speaking, two important stages should be carefully considered:

- •

the elaboration and implementation of the programme of care, with special attention to the qualitative and quantitative description of the local context, the reasons for creating such a programme and the choices that had to be made based on the available resources;

- •

the assessment of the outcomes in a programme that is already stable organisationally. The difficulties encountered, the problems that had to be solved, and the pitfalls that should be avoided are also interesting to report. These factors can become the starting point for new programme developments, as is done in the Deming Wheel ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1

The Deming Wheel.

From Wikipedia Commons.

Completing both these stages is not required before submitting a PRM-PC for European PRM Accreditation. In fact, if the process has been carefully managed, the first stage will elicit very useful information. Implementing the second stage doesn’t mean an extensive assessment of numerous parameters, which is likely to be incompatible with a normal daily practice.

It is useful to underline the difference between a clinical research programme and an assessment of a PRM-PC:

The general goal of clinical research is to give the most definite answer to a simple and concise question. Methodological bias is one of the researcher’s major concerns. To avoid bias, researchers must gather the most homogeneous population, control as many parameters that may influence the results as possible, perform perfectly scheduled and invariable interventions, evaluate the results according to multiple parameters and techniques, and observe whether or not these results agree.

A programme of care, on the other hand, tries to intervene efficiently in the widest possible population. In daily practice conditions, this population is defined only by the problem to be treated, the goal to be attained, and the potential compliance with the scheduled intervention. For instance, a follow-up programme for patients who have had anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction can be applied, subject to a few adaptations, to the reconstruction of the posterior cruciate ligament or to the reparation of complex knee damage. Of course, for each sub-group, it will be necessary to adjust the goals and the treatment schedule and to specify the precautions and specific measures that need to be taken.

Routine assessment in daily clinical practice may address a limited number of parameters only, which should be chosen as significant indicators of patient progress or difficulties and of programme efficiency. Based on our own experience, in a normal consultation, it is difficult to handle more than about ten parameters in real time. Beyond this number, the practitioner’s attention is distracted by the technical aspects of the assessment, to the detriment of the general issue of the patient who is consulting. The nature of the consultation changes, and it becomes impossible, in a limited period of time, to deal simultaneously with the therapeutic, educational and psychological aspects, which are certainly as important as the assessment.

Clearly, working in a team may help to better distribute the tasks, especially those related to relatively sophisticated and time-consuming tests. Nevertheless, cost has to be taken into consideration and maintained under a reasonable level, without causing prejudice to tangible patient care. In other words, the patients are “customers” who deserve the best service possible. They shouldn’t become, without their knowledge, an object of study for the practitioner’s convenience. This may explain why it is sometimes difficult to integrate certain comprehensive assessment tools into daily clinical practice.

The choice of criteria and assessment methods is therefore a compromise between the assessments goals and the available resources. These choices may evolve over time: certain parameters seem to be redundant, always obtaining the same score at the same stage of the programme or proving to have no practical significance, while other parameters can reveal a real dysfunction, or, on the contrary, a sufficient performance level to allow the next programme stage to begin. All these ideas are worth being expressed in the description of the care programme.

1.5.3

Scientific foundations of the programme

A PRM programme of care has to meet the requirements of evidence-based medicine. This criterion was designed to prevent us from accrediting outdated or esoteric methods. With this in mind, UEMS required that five scientific papers and/or professional recommendations be cited in the original accreditation questionnaire.

Citing national recommendations was a subject of debate about the place of these recommendations in a European accreditation. All the details of this discussion were reported along with the CAC Action Plan, published in the European journal of rehabilitation medicine . The easiest way suggested was to accept Anglophone documents only, especially the papers referenced in the PubMed database and the recommendations published by the Cochrane library. However, equating “International” and “Anglophone” was considered as a way to artificially impose a single culture, ignoring all the research done in all European countries in each of the 23 officially-recognized European languages .

The CAC thus decided to recognize national references and recommendations, provided that their sources are well identified and accessible, and that their content could be easily understood ( Appendix C ). For this reason, every author is kindly requested to write a short summary of any national documents in English when an English version is not available. Furthermore, a working group was set up to compile the national sources of scientific documents and professional recommendations in PRM. This should be done in cooperation with the Guidelines international network (GIN) , which is linked to the UEMS, to the European society of PRM (ESPRM) and to national scientific societies. These national societies have been invited to sign a cooperation agreement with the UEMS PRM section and board. The SOFMER (France) , the SIMFER (Italy) and the Hellenic Society of PRM have already done so.

However, referring to scientific literature and to recommendations for good clinical practice cannot be limited to a simple listing of titles, automatically provided by any search engine. Relevant data and immediately applicable recommendations are still too scarce to neglect a real bibliographic research, which has to be organized in accordance with the care programme project.

This is why every reference has to now be cited in the text describing the preliminary approach and in the programme content itself, and can no longer be simply listed out of any context, as was true in the first version of the accreditation questionnaire.

1.5.4

Questionnaire and text description

Using multiple-choice questions (MCQ) has several advantages: a well-controlled study domain, simplified participation for the applicant, and the ease with which statistics can be obtained from the answers. The drawback of a MCQ questionnaire is that it imposes a conceptual framework, which may not correspond to the real approach with which the programme was developed. The responses, as well as their interpretation, may therefore be biased or their usefulness reduced. This was clearly demonstrated by the jury’s comments and the numerous requests for additional information sent to the applicants.

Consequently, the new accreditation application form contains a free text zone for a description of the programme director’s approach under each questionnaire section. Moreover, two important sections have been added to the form:

- •

general programme foundations, consisting of information about the impairment (etiology, pathogeny, natural path, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment), activity limitations and participation restrictions, social and economic consequences, while highlighting the national and local context and the programme’s main principles;

- •

the description of the programme content:

- ∘

diagnosis and initial assessment of the impairment, activity limitations and participation restrictions, as well as environmental factors and personal demands;

- ∘

intervention, with details about the strategic timeframe, the role played by the PRM specialist, the team’s interventions, including the specific participation of each team member;

- ∘

follow-up and results

- ∘

programme closure and long-term follow-up.

- ∘

1.5.5

References to ICF

The decision to encourage the use of ICF in clinical practice was officially approved in March 2007 by the General assembly of the UEMS PRM section (Rennes, France), and this decision has been included in the PRM White Book . Thus, ICF terms have voluntarily been used in the application form for PRM-PC accreditation. Furthermore, applicants are requested to mention several ICF labels in the definition of the goals of their programmes of care. For this purpose, we recommend using the ICF Browser .

1.5.6

Organizational issues

In the accreditation questionnaire, the applicant is requested to answer some questions about organisational aspects of the programme (i.e., patient referrals, inpatient or outpatient programme, multidisciplinary care, special facilities), safety rules and patients rights, team cooperation and the specific role played by the PRM Specialist, patient records and information management, programme monitoring and quality assurance approach.

In addition to describing the equipment and human resources, explaining the organisation of the human resources and the usefulness of the equipment in the context of the Programme of Care is very much recommended.

1.5.7

The accreditation process: from jury assessment to a conceptual laboratory

During the pilot phase, the jury-voting algorithm was replaced early on by interaction with the applicant. Consequently, the accreditation process turned into a peer-review process, which was more appropriate to the European situation than a standardized screening system.

Thus, the word “Jury” was abandoned in favour of “Reviewers group” in our terminology. The mission of the reviewers is now to guide the applicants’ efforts to formulate the best possible description of their programmes and to help them to provide the highest level of information that would be interesting for the European PRM community and all their partners. In this way, the European PRM accreditation system will become a real laboratory of ideas for developing and assessing PRM-PCs, to everyone’s benefit.

Using the English language is the only way to overcome linguistic barriers, but this should not discourage applicants who are not fluent in English. Their texts are expected to be understandable by everybody but UEMS will not impose excessively formal requirements at this stage of the communication.

In a second step, accredited programme directors will be invited to present their works in “Quality of PRM care” sessions, which will be organized by the PRM section and board in several international and national congresses. Sessions of this kind have already been scheduled for the International society of PRM (ISPRM) congress in Istanbul (Turkey) in June 2009, the SOFMER congress in Lyon (France) in October 2009, and the European PRM (ESPRM) Congress in Venice (Italy) in May 2010. These programme directors will also be encouraged to publish their PRM-PC in several PRM journals, whose editors-in-chief participated in the Cambridge general assembly (March 2009) and all expressed their interest in this kind of paper. Programmes that best represent the PRM Specialty will be collected and published (subject the author’s agreement) in the forthcoming “eBook on quality in PRM programmes of care”. This electronic book will be available to the PRM Specialists online in 2010.

1.6

Conclusion

The Clinical affairs committee (CAC) of the UEMS PRM Section has implemented a European accreditation system for PRM programmes of care. After a pilot phase, which proved the value of such a process, the CAC has upgraded the system by adding a detailed description of the candidate programmes to the original questionnaire. Our final goal is to allow the accredited programmes to be published in PRM congresses and journals, as well as in an electronic book, called the “eBook on quality in PRM programmes of care”. This eBook will be available in 2010 on the website of the PRM Section: www.euro-prm.org .

On a scientific level, the PRM-PC concept will be precious for:

- •

describing the daily PRM activity;

- •

identifying general and specific patient cohorts and flows;

- •

emphasizing the physician’s role in the care programme;

- •

defining the place of assessment and/or treatment techniques;

- •

studying the results obtained.

For potential applicants, the UEMS European accreditation offers considerable benefits: the improvement of the quality of patient care, the recognition of the PRM programmes by a European structure, visibility through the display of the accredited programme on a public website, advice from a panel of PRM experts, the example offered by the already accredited programmes, participation in a European quality network of accredited programmes, an active contribution to the comprehensive description of the PRM specialty, and the opportunity to participate in International and national congresses and to publish in PRM Journals.

We hope that the participation of PRM specialists in the accreditation process will facilitate the development of a European PRM culture of quality of care, which will help patients find the care they deserve, provide good examples and advice to physicians, and give decision-makers good reasons to foster the development of our specialty with sufficient resources.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

List of programs accredited during the pilot phase

The original list in English is available at www.euro-prm.org .

| N | Author’s name | First name | City | Country | Programme title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Quittan | Michael | Vienna | Austria | Post-traumatic geriatric rehabilitation |

| 3 | Fialka-Moser | Veronika | Vienna | Austria | Rehabilitation of cancer patients |

| 4 | De Korvin | Georges | Rennes | France | General physical and rehabilitation medicine |

| 5 | Goljar | Nika | Ljubljana | Slovenia | PRM and stroke patients |

| 6 | Denes | Zoltan | Budapest | Hungary | PRM and patients with neurological disorders |

| 9 | Giustini | Alessandro | Pisa | Italy | PRM and patients with neurological disorders |

| 17 | Delarque | Alain | Marseille | France | Assessment and treatment of patients with gait disorders in an ambulatory service in acute care setting |

| 18 | Kesiene | Jurate | Vilnius | Lithuania | PRM and patients with spinal cord injuries |

| 19 | Presern-Strukelj | Metka | Ljubljana | Slovenia | Amputee rehabilitation |

| 21 | Damjan | Hermina | Ljubljana | Slovenia | Inpatient rehabilitation programme for children |

| 22 | Sinocevicius | Tomas | Vilnius | Lithuania | PRM and stroke patients |

| 24 | Bors | Katalin | Visegrad | Hungary | PRM and patients with osteoporosis |

| 26 | Boros | Erzsebet | Budapest | Hungary | PRM programme for adults with neurological disorders |

Appendix B

Submission template for a PRM programme of care

Approved by the General Assembly of the UEMS PRM Section, the original template in English is available at www.euro-prm.org .

The general programme foundations:

- •

Pathological and impairment considerations (aetiology and pathogeny, natural history and impairment relationship, medical diagnosis and prognosis, treatments)

- •

Activity limitations

- •

Participation restrictions

- •

Social and economic consequences (epidemiological data, social data, economic data)

- •

Main principles of the programme

Programme aims and goals:

- •

Target population (inclusion/exclusion criteria, patient referrals, recovery stages)

- •

Programme objectives (in terms of activity, participation and body structure & function)

Programme environment:

- •

Clinical setting

- •

Clinical programme

- •

Clinical approach

- •

Facility

Safety and patient rights:

- •

Safety

- •

Patient rights

- •

Advocacy

PRM Specialist and team management:

- •

Role of the PRM Specialist in the programme (responsibilities and interventions)

- •

Team management (resources, training, organisation)

Programme description:

- •

Assessment (diagnosis, impairment, activity and participation, environmental factors)

- •

Intervention (programme schedule, PRM specialist intervention, team intervention)

- •

Follow-up and outcomes (review and progress during the rehabilitation programme, criteria for measuring progress)

- •

Discharge plan and long-term follow-up

Information management:

- •

Patient records

- •

Management information

- •

Programme monitoring and outcomes

Quality improvement:

- •

What are the strongest points of the programme?

- •

What are the weakest points of the programme?

- •

What action plan do you intend to implement in order to improve the programme?

References:

- •

List of references

- •

Details about national documents

Appendix C

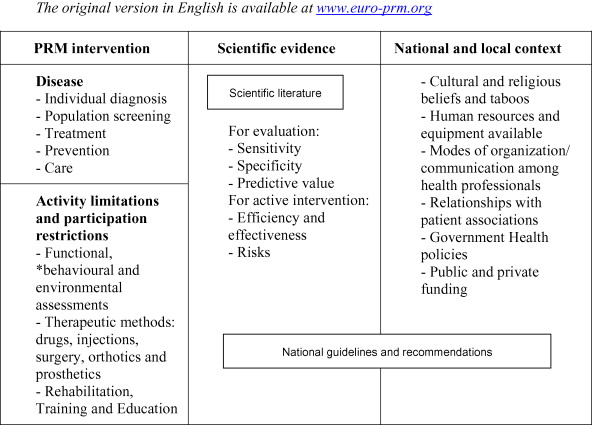

Place of EBM and National guidelines for Good Clinical PRM Practices

The original version in English is available at www.euro-prm.org .

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La section et le board MPR de l’Union européenne des médecins spécialistes (UEMS) sont composés de délégués représentant, à présent, 31 pays européens . Les délégués se réunissent lors des deux assemblées générales annuelles. Durant trois jours, ils travaillent au sein de trois commissions :

- •

le Board ou Commission pour l’éducation ;

- •

la Commission des pratiques professionnelles qui s’intéresse au domaine de compétence de la MPR ;

- •

la Commission des affaires cliniques (CAC).

La CAC a centré ses travaux sur la qualité des soins (QDS) MPR. Sous la présidence du Pr Bengt Sjölund, délégué suédois, nous avons réfléchi de 2001 à 2004 aux fondements éthiques d’une telle démarche, à ses perspectives en matière de recherche clinique et, finalement à une application pragmatique et concrète.

Cela a abouti, en 2004, à retenir le concept de programme de soins en MPR (PDS) comme base de travail et à élaborer un dispositif d’accréditation européenne des programmes de soins en MPR, que nous voulions simple à utiliser et à gérer. Un questionnaire en ligne a été mis en place sur un site Internet et une phase pilote a permis l’accréditation de 13 PDS par un jury européen de cinq membres de nationalités différentes.

Cette phase d’essais, de 2006 à 2008, a montré la faisabilité d’un tel projet. Mais elle a aussi soulevé de nombreuses questions sur les échanges d’information entre jury et candidat, la structure et la forme du dossier de soumission d’un PDS, les relations entre fondements scientifiques (publications et recommandations internationales et/ou nationales) et pratique clinique, enfin et surtout, l’intérêt de participer à une telle accréditation.

Cette réflexion européenne a également nourri la démarche du syndicat français de médecine physique et de réadaptation (SYFMER) et conduit à introduire, début 2009, le concept de programme de soins en MPR dans la négociation avec l’assurance maladie (UNCAM) sur la mise à la tarification d’actes d’évaluation fonctionnelle instrumentale, à savoir la dynamométrie isocinétique et la topographie de surface. La réaction plutôt favorable de nos interlocuteurs à cette approche, a donné un nouvel élan à la démarche européenne, tout en influant sur ses modalités.

C’est ainsi que, depuis l’assemblée générale de Cambridge, en mars 2009, un nouveau dispositif a été mis en place, sur le site www.euro-prm.org . Alors que le questionnaire initial était très orienté vers les aspects organisationnels, le nouveau modèle se veut centré sur les fondements du programme (données de base) et sur le contenu élaboré par le spécialiste MPR en réponse aux besoins des patients. L’accréditation ne se veut plus un processus de contrôle sélectif, mais plutôt un laboratoire d’élaboration de la pratique clinique en MPR, où le candidat sera guidé pour traduire son expérience de la manière la plus valorisante et la plus profitable pour le patient et pour d’autres spécialistes MPR.

Cet article retrace notre démarche et nos discussions jusqu’au dispositif actuel qui est ensuite décrit en détail. Il se termine par des recommandations qui devraient faciliter la participation de tout médecin MPR à cette Accréditation européenne des programmes de soins, qui devrait rendre notre spécialité plus visible et lisible dans l’ensemble des pays d’Europe, dans l’intérêt des patients.

2.2

Objectifs

Assurer la meilleure qualité des soins possible est une obligation éthique pour tout médecin. Mais au-delà de l’engagement personnel, cette démarche a commencé à être formalisée par des précurseurs, comme les frères Mayo, dont les préceptes restent d’actualité .

Sur le plan juridique, le Conseil de l’Europe a émis en 1997 la recommandation n o R(97) 17 sur le développement et la mise en place de systèmes d’amélioration de la qualité des soins .

L’UEMS s’est saisie très tôt de ce sujet. Elle adopta dès 1996 une première Charte européenne sur l’assurance qualité en pratique médicale spécialisée . Plus récemment, la qualité des soins a fait l’objet de trois documents de consensus :

- •

la déclaration de Bâle , qui est une charte sur la formation professionnelle continue ;

- •

promouvoir des soins médicaux de bonne qualité ; ce document d’orientation stratégique définit l’assurance qualité comme un processus de révision régulière plutôt que la mise en application de standards de soins prédéfinis ;

- •

la déclaration de Budapest sur l’assurance de la qualité des soins médicaux (UEMS 2006/18) , qui définit la politique de l’UEMS en matière de réglementation médicale : tout dispositif de contrôle doit prendre en compte le contexte de la pratique médicale, les attentes de la société et les ressources disponibles pour assurer les soins médicaux.

Autrement dit, comment promouvoir la qualité des soins dans une Europe en pleine évolution, avec l’arrivée des nouveaux pays entrant dans la Communauté ? Comment prendre en compte une situation hétérogène et mal connue, sans céder aux clichés de supposés gradients Nord-Sud ou Est-Ouest ? Comment aborder la qualité des soins au sein d’une spécialité qui ne peut se définir par rapport à un territoire anatomique ni à une technologie univoque, mais s’appuie sur un consensus philosophique, certes bien partagé dans le monde entier ?

À côté des débats conceptuels, il nous a paru essentiel de faire émerger une information « brute », issue de la pratique clinique de terrain, sans chercher à imposer, a priori, un cadre d’appréciation importé d’un pays ou d’un autre, ni même, des échelles de valeur présupposées.

Dans cette optique, le concept de programme de soin en MPR nous a rapidement paru la meilleure base pour développer une démarche européenne portant sur la qualité des soins. Le programme de soins en MPR se veut être la réponse la mieux adaptée aux besoins d’une population. Le spécialiste de MPR, qui en est le responsable, doit le décrire sur la base des items suivants :

- •

les fondements généraux du programme : pathologie, déficience et handicap, conséquences socio-économiques, principes du programmes ;

- •

les objectifs du programme : la population cible, les buts à atteindre, en utilisant les termes de la CIF ;

- •

le contenu du programme : l’évaluation (diagnostic pathologique, déficience et handicap, facteurs environnementaux), les interventions (calendrier, intervention directe du spécialiste MPR, actions de l’équipe), suivi et résultats, plan de sortie et suivi à long terme ;

- •

l’environnement et l’organisation du programme : structure de prise en charge, adressage ou accès direct, internat ou différentes formes ambulatoires, travail en équipe ou en réseau, locaux dédiés, sécurité et droit des patients, information, rôle des spécialistes MPR dans le programme, gestion d’équipe ;

- •

gestion de l’information : données du patient, informations sur la prise en charge, suivi des résultats ;

- •

amélioration de la qualité : points forts et points faibles du programme, plan d’amélioration de la qualité ;

- •

références : publications scientifiques et recommandations citées dans le texte de description du programme ; détails explicitant les documents nationaux.

Dans les pays européens, les systèmes de certification et d’accréditation obligatoires sont centrés, soit sur les médecins, soit sur les établissements. Nous n’avons pas trouvé de dispositif spécifique de la MPR. En France, l’accréditation des établissements contient des adaptations propres aux services de suite et de réadaptation, don la MPR fait partie.

Sous la présidence du Pr Bengt Sjölund, nos regards se sont tournés vers l’Amérique du Nord où le concept de programme de soins est établi de longue date. Dès le II e congrès international de l’accréditation en santé (Marseille – 2000), le Pr Yves-Louis Boulanger montrait comment les programme de soins étaient conçus à Montréal , tandis que le dispositif d’accréditation mis en place aux USA par la Commission d’accréditation des établissements de réadaptation (CARF), était présenté par Christine Mac Donnell .

Néanmoins, les procédures d’accréditation organisées Outre-atlantique, intégrées dans un dispositif de santé assurantiel très différent des différents systèmes européens de financement des soins, ne pouvaient être étendues telles quelles à un ensemble de pays aux cultures et législations très diverses, mais imposant déjà une charge administrative très lourde aux médecins.

Le motif de cette accréditation européenne ne reposant ni sur une obligation légale, ni sur un bénéfice financier immédiat, nous avons imaginé une procédure allégée, peu coûteuse en temps et en argent, et visant deux objectifs :

- •

mieux faire connaître de tous les publics (du patient aux autorités de tutelle) les soins de qualité proposés par la MPR ;

- •

initier une dynamique d’amélioration continue de la qualité. Cela devait se faire sans jugement de valeur a priori, mais en cherchant à mettre en valeur les pratiques cliniques existantes dans les différents pays européens.

Il nous a paru également important d’organiser un système d’accréditation dirigé par les médecins MPR eux-mêmes, avant que d’autres se chargent de nous imposer un dispositif dont nous ne contrôlerions ni la conception, ni l’organisation, ni les données produites.

2.3

Méthode : la phase pilote

En septembre 2004, à Dublin, l’assemblée générale de la section MPR de l’UEMS décida la création d’un système d’accréditation européen des programmes de soins. En février 2005, à Hanovre, elle approuva les spécifications élaborées par la Commission des affaires cliniques et en septembre 2005, à Limassol, nous pouvions présenter une première maquette du dispositif, qui devait ensuite subir un certain nombre d’évolutions.

Le principe était d’organiser sur Internet une réponse en ligne à un questionnaire auto-déclaratif, permettant une description concise du programme de soins et d’en évaluer les principaux aspects : cible, objectifs, organisation. Nous y reviendrons plus en détail en décrivant la version finale.

Chaque programme inscrit en ligne était soumis à l’appréciation d’un jury européen de cinq membres. Le logiciel permettait de traiter les votes de manière automatique et de collecter les commentaires des jurés. La première phase de tests en vraie grandeur fut lancée en 2006. Très rapidement est apparue la nécessité d’organiser un échange d’informations entre le jury et les candidats, afin d’expliciter les réponses binaires (oui ou non) au questionnaire, d’enrichir et d’améliorer la description du programme en texte libre. C’est ainsi qu’en 2007, nous avons introduit un espace de dialogue réservé aux membres du jury ( Jury’s corner ) et un échange anonyme entre le jury et le candidat.

2.4

Résultats

Durant cette phase pilote de deux ans, 13 programmes ont été accrédités ( Annexe A ). Les pays représentés sont l’Autriche (deux programmes), la France (deux), la Hongrie (trois), l’Italie (un) et la Lituanie (deux), la Slovénie (trois), ce qui correspond à une intéressante répartition Est-Ouest et montre l’implication des nouveaux pays européens dans notre démarche.

Les candidats avaient la possibilité de choisir un titre proposé dans un menu déroulant ou de créer un titre de programme original. Sept titres ont porté sur la MPR appliquée à des atteintes du système nerveux, dont trois programmes ciblés sur l’accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC) et un programme spécifique des lésions médullaires.

Deux programmes s’intitulaient « programme de MPR générale », dont l’un portant spécifiquement sur les enfants. Les cinq autres programmes portent des titres divers : « évaluation et traitement de patients avec troubles de la marche », « prise en charge post-traumatique des personnes âgées », « amputés », « patients ostéoporotiques », « réadaptation des patients cancéreux ». Cela montre l’importance du pôle d’intérêt neurologique, mais aussi la diversité du champ d’application de la MPR dans différents pays d’Europe. Enfin, les deux programmes de « MPR générale » montrent qu’il n’est pas nécessaire d’appartenir à une grosse structure hyper spécialisée pour soumettre un programme de soins à l’Accréditation européenne.

Nous avons enregistré un certain nombre de soumissions incomplètes, généralement effectuées à titre d’essai. Mais tous les programmes sérieusement présentés ont fini par être accrédités, lorsque les candidats ont fait l’effort d’apporter les compléments d’information et les corrections de forme demandées par le jury.

Au fur et à mesure du déroulement de la phase test, une série de 12 critères d’appréciation a émergé des débats, généralement consensuels, du jury :

- •

les objectifs du programme sont bien décrits et exprimés en référence à la CIF ;

- •

les bases scientifiques (Médecine fondée sur les preuves) sont claires ;

- •

les critères d’admission et de fin de prise en charge sont bien définis ;

- •

le nombre de patients traités par an paraît adapté ;

- •

les moyens humains (compétences et nombre d’intervenants) paraissent adaptés ;

- •

une formation continue du médecin et de l’équipe est organisée ;

- •

l’intervention du médecin MPR est partie intégrante du programme ;

- •

le médecin joue un rôle actif dans la réadaptation et ne porte pas seulement sur le traitement des comorbidités ;

- •

le programme respecte les droits des patients ;

- •

le programme respecte les obligations de sécurité ;

- •

le dossier médical est convenablement tenu et il intègre les données de réadaptation ;

- •

les résultats du programme sont suivis et une démarche d’amélioration de la qualité est mise en place.

Le Pr Alvydas Juocevicius (Lituanie) et son équipe ont analysé l’ensemble des réponses collectées à partir des programmes accrédités. Le taux de réponses positives aux différentes questions est généralement élevé. Un score de 100 % a été enregistré pour trois items :

- •

l’intervention du médecin MPR est partie intégrante du programme ;

- •

le médecin joue un rôle dans le processus de réadaptation ;

- •

le dossier médical est convenablement organisé et intègre les données de réadaptation.

Les deux premières questions peuvent paraître couler de source dans certains pays comme la France. Mais cela n’est pas le cas dans certains pays où l’on conçoit qu’un programme de réadaptation puisse être coordonné par un non-médecin (infirmière, kinésithérapeute ou autre « référent ») tandis que le rôle du médecin se limite à traiter les « comorbidités ». Certaines questions ont donc une vocation « pédagogique » !

Les scores les plus faibles ont été enregistrés pour deux questions :

- •

50 % pour un lien clairement établi avec la « médecine fondée sur les preuves » (EBM) ;

- •

57 % pour une définition claire des critères d’admission et de sortie des patients.

Le questionnaire se terminait par trois questions visant à initier une démarche d’amélioration de la qualité :

- •

quels sont les points forts de votre programme ?

- •

quels sont les points faibles de votre programme ?

- •

quel plan d’action envisagez-vous de mettre en place pour améliorer votre programme ?

Les points forts mentionnés portent sur deux aspects complémentaires :

- •

le service directement offert au patient : une prise en charge MPR complète et individualisée (6/13), une évaluation complète avant la mise en place d’une réadaptation ambulatoire (2/13), une bonne efficacité thérapeutique (3/13), une bonne collaboration avec l’entourage familial du patient (1/13) ;

- •

l’aspect organisationnel qui, bien sûr, profite également au patient : le travail en équipe multiprofessionnelle (9/13), une démarche interdisciplinaire (5/13), l’organisation de programmes de recherche et d’enseignement liés à la pratique clinique quotidienne (3/13), une gestion d’équipe en coopération avec un partenaire étranger (1/14).

Les points faibles portent sur :

- •

l’insuffisance des moyens alloués au programme : manque de lits dédiés à la réadaptation précoce de patients amputés ou de patients cancéreux (2/13), discipline non représentée dans l’équipe de réadaptation (neuropsychologue, orthophoniste, ergothérapeute – 3/13) ;

- •

l’insuffisance de certains aspects de la prise en charge : rééducation des fonctions supérieures (3/13), soins d’ergothérapie et réadaptation socioprofessionnelle (6/13)

- •

l’insuffisance d’évaluation des résultats du programme.

Les plans d’amélioration du programme de soins portent sur deux aspects :

- •

les moyens alloués, ce que l’on peut qualifier de facteur extérieur : davantage de lits d’hospitalisation ou de places ambulatoires (2/13), davantage de spécialistes (2/13), création d’un secteur de réadaptation professionnelle (1/13), amélioration de l’équipement, en fonction des ressources financières (1/13), mise en place d’un système informatique (3/13) ;

- •

L’organisation elle-même, qui relève plus directement du responsable du programme de soins : la mise à jour des procédures existantes et la définition de nouvelles procédures au sein d’un programme de MPR générale (1/13), l’amélioration de la rééducation cognitive pour les patients victimes d’AVC (1/13), la mise en application de la CIF (2/14), la formation continue de l’équipe (1/13), l’amélioration de l’évaluation continue du programme (3/14).

2.5

Discussion : de la phase-pilote à la nouvelle procédure

La phase pilote de notre dispositif d’accréditation européenne des programmes de soin en MPR a été présentée dans plusieurs congrès de MPR : les congrès SOFMER de Saint-Malo (2007) et de Mulhouse (2008), le Congrès européen de Bruges (2008), le congrès SIMFER de Rome (2008), le congrès de la Baltique à Riga (2008).

Les discussions avec le public de ces congrès, les débats au sein de la Section et du Board de l’UEMS, les échanges entre jury et candidats, nous ont convaincus de l’intérêt de cette démarche, mais aussi de certaines de ses faiblesses, ce qui nous a conduits à en proposer l’amélioration. Le nouveau modèle de présentation d’un programme est reproduit en Annexe B .

2.5.1

Point fort et point faible du dispositif pilote

Le point fort est d’apporter des informations structurées sur les programmes de MPR européens, quels qu’en soient l’objet, les moyens ou la forme d’organisation. C’est donc un formidable outil pour mieux connaître et faire connaître la MPR telle qu’elle est réellement pratiquée, dans toute sa diversité et sa richesse.

Le point faible est la difficulté rencontrée pour appréhender certains programmes. Cela s’est traduit par les nombreuses interrogations du jury quant à la pertinence des réponses aux questions sensées décrire le programme. Plusieurs fois, il est apparu que le programme avait un domaine d’application trop large pour que certaines questions soient applicables. Par ailleurs, si le formulaire comportait bien une place pour une description ouverte du programme, celle-ci s’est souvent révélée trop succincte pour se faire une idée précise du contenu exact du programme.

Nous avons ainsi constaté que la procédure testée dans la phase pilote avait prévu une place insuffisante au contenu proprement dit du programme et à la description détaillée du rôle du médecin MPR au sein du programme. De fait, les systèmes d’accréditation existants, instaurés par des non-médecins, sont naturellement centrés sur les aspects organisationnels et non sur des considérations médicales que leurs initiateurs ne pouvaient maîtriser.

2.5.2

Les informations générées par le concept de programme de soins

Nos récentes discussions avec l’Assurance Maladie française nous ont également montré l’importance de disposer d’informations quantitatives concernant :

- •

l’amont d’un programme – données épidémiologiques et socioéconomiques ;

- •

son déroulement – taux de participation, temps de traitement, quantification des moyens mis en œuvre (y compris les prescriptions) ;

- •

son aval – résultats obtenus, mais aussi différentiel par rapport à la non-applicationn d’un tel programme (plus ou moins de prescriptions, de jours d’arrêt maladie, nomadisme médical, etc.).

On imagine donc facilement toute la richesse des informations susceptibles d’être produites par la description de programmes de soins en MPR. Bien sûr, il ne saurait être question pour une seule équipe, même très étoffée, de balayer d’un coup tous les aspects évoqués. De manière pragmatique, deux étapes méritent toute notre attention :

- •

la mise en place d’un programme de soin, avec la description précise du contexte local (qualitatif et quantitatif), des motifs qui décidé la création du programme, des bases scientifiques et des choix qu’il a fallu faire en fonction des moyens alloués ;

- •

L’évaluation des résultats d’un programme déjà bien stabilisé dans son organisation, les difficultés enregistrés, les problèmes qu’il a fallu résoudre, les pièges à éviter. Cela peut être le point de départ à de nouvelles évolutions du programme de soins, comme l’évoque la « roue de Deming » ( Figure 1 ).