Esophageal dysphagia can arise from a variety of causes such as motility disorders, mechanical and inflammatory diseases. Adequate management includes a detailed history, evaluation with upper endoscopy, barium radiography and manometry. Treatment is usually tailored to the underlying disease process and in some cases, as in inoperable cancer, palliative management may be necessary.

Dysphagia is the sensation of food being hindered during the passage from the mouth through the esophagus and into the stomach. Dysphagia is traditionally classified as oropharyngeal or esophageal dysphagia. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is the inability to initiate a swallow or inability to transfer food from the mouth to the upper esophagus whereas esophageal dysphagia is the impedance of food passage through the tubular esophagus once the food has successfully passed into the proximal esophagus.

A variety of mechanical and neuromuscular disorders can impede the passage of the food bolus through the esophagus ( Table 1 ). Patients who have an inflammatory process may have associated odynophagia. Most patients often report food “hanging up” or “sticking” behind the sternum and lump or food being caught at the epigastrium. Patients are able to localize the site correctly in only 70% of cases, with 30% localizing the dysfunction proximally in the esophagus, suprasternal notch, or the throat.

| Mechanical disorders | Neuromuscular disorders | Inflammatory process |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic causes | ||

|

|

|

| Extrinsic causes | ||

|

Evaluation of patients with esophageal dysphagia

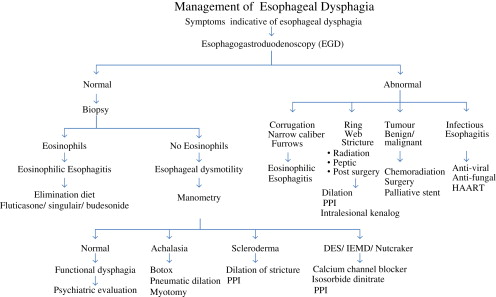

The importance of detailed medical history cannot be overemphasized in the evaluation of patients presenting with dysphagia . Careful history about the type of food that causes symptoms is extremely important as patients may present with solid and/or liquid food dysphagia. Isolated solid food dysphagia suggests a mechanical cause for symptoms whereas both solid and/or liquid food dysphagia points to a neuromuscular etiology. Duration and temporal progression of symptoms are also important; intermittent symptoms may suggest a mechanical cause, such as Schatzki’s ring (solid dysphagia) or a neuromuscular disorder, such as esophageal spasm (solid and liquid dysphagia). A short-duration and rapidly progressive dysphagia is concerning for malignancy. Solid food dysphagia progressing to liquid dysphagia suggests a mechanical problem, which may be benign (peptic stricture) or malignant (adenocarcinoma). Other symptoms such as weight loss, regurgitation of food particles, heartburn, pain during swallowing, or chest pain, as well as medications may give important clues to the etiology of dysphagia. Heartburn symptoms in a patient with dysphagia may suggest complications from acid reflux-induced peptic stricture or adenocarcinoma (solid only or solid progressing to liquid) or scleroderma esophagus (both solid and liquid dysphagia). The caveat is that 25% to 30% of patients presenting with dysphagia due to peptic stricture or adenocarcinoma do not have heartburn at the time of diagnosis . An algorithm for evaluating patients with esophageal dysphagia is shown in the following paragraphs ( Fig. 1 ).

Investigation of patients with esophageal dysphagia should be based on history. If the history is suggestive of a mechanical disorder, upper endoscopy or barium radiography should be requested. However, if history is suggestive of a motility disorder, then manometry is the first diagnostic test. Upper endoscopy is recommended to assess mucosa injury, provide opportunity for biopsy to rule out microscopic disease in a normal appearing esophagus, and to perform therapeutic intervention such as dilatation. Barium radiography with barium-impregnated marshmallow or barium tablet challenge may identify intraesophageal structural abnormalities, site, and length of stricture. High-resolution esophageal manometry is the gold standard for evaluating suspected motility disorder and should be requested if upper endoscopy and radiological studies are negative. The diagnostic algorithm for esophageal dysphagia is shown in Fig. 2 .

Epidemiology, etiology, clinical features, and management of differential diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia

Esophageal rings and webs

Esophageal webs are thin mucosal folds that protrude into the lumen and are covered with squamous epithelium. They can be congenital or acquired; congenital webs are rare, seen in pediatrics and usually occur in the middle and lower thirds of the esophagus. They arise from failure of complete coalescence of esophageal vacuoles during embryologic development . Acquired webs are more common than congenital webs and are often located in the cervical esophagus in the post-cricoid region, causing luminal narrowing and dysphagia. Cervical webs are typically diaphragm-like in nature.

Most patients with esophageal webs are asymptomatic and thus the true prevalence of acquired webs is unknown. Esophageal webs are twice as common in women as in men , with symptoms occurring more commonly in women than in men. Acquired esophageal webs have been reported in association with gastroesophageal reflux disease and iron-deficiency anemia as in Plummer-Vinson syndrome or Paterson-Kelly syndrome. Others include their association with dermatologic or systemic diseases, such as pemphigus vulgaris , epidermolysis bullosa , bullous pemphigoid , and desquamative esophagitis in chronic graft-versus-host disease .

Esophageal rings are usually seen in the lower third of the esophagus. There are two types; A (muscular ring) and B (mucosal ring or Schatzki). Muscular rings are rare and seldom cause dysphagia. They are frequently seen in children undergoing barium study for other reasons. They are located within 2 cm of the squamocolumnar junction and are due to muscular hypertrophy. In contrast, Schatzki’s ring is located at the squamocolumnar junction. The upper part is covered with squamous- and the lower part with columnar epithelium. The ring is a thin (<4 mm in axial length) smooth mucosa tissue. It is seen in 6% to 14% of asymptomatic patients during routine barium studies . Schatzki’s ring is seen in a quarter of patients with esophageal dysphagia and may be seen in association with patients who have eosinophilic esophagitis . It is more common in older patients (>40 years) but can also be seen in younger patients. The etiology of esophageal rings is unclear. There are inconclusive evidences implicating gastro esophageal reflux disease (GERD) in the pathogenesis of Schatzki’s rings .

Patients with esophageal web and Schatzki’s ring present with episodic solid food dysphagia. This frequently occurs after rapid ingestion of a bolus and when luminal diameter is less than 13 mm. In addition, patients with post-cricoid web may have nasopharyngeal reflux and/or aspiration. The dysphagia is transient, and if the bolus passes, the rest of the meal can be consumed without incident. However, some patients may present with acute bolus impaction. Physical examination may reveal features of associated medical conditions, such as bullous skin lesions and koilonychia in patients with webs. Diagnosis in both disorders is by barium swallow and/or esophagram and upper endoscopy.

Mechanical dilation is the treatment of choice for symptomatic patients. This can be accomplished by using a series of dilators over a guide wire (American dilators) or through scope balloon (controlled radial expansion [CRE]) dilators . Endoscopic incisions of recurring lower esophageal ring have also been reported . In patients with underlying medical conditions, such as eosinophilic esophagitis, GERD, dermatologic or chronic graft-versus-host disease, and iron-deficiency anemia, aggressive treatment of the underlying medical condition should be embarked on, before and after dilatation.

Epidemiology, etiology, clinical features, and management of differential diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia

Esophageal rings and webs

Esophageal webs are thin mucosal folds that protrude into the lumen and are covered with squamous epithelium. They can be congenital or acquired; congenital webs are rare, seen in pediatrics and usually occur in the middle and lower thirds of the esophagus. They arise from failure of complete coalescence of esophageal vacuoles during embryologic development . Acquired webs are more common than congenital webs and are often located in the cervical esophagus in the post-cricoid region, causing luminal narrowing and dysphagia. Cervical webs are typically diaphragm-like in nature.

Most patients with esophageal webs are asymptomatic and thus the true prevalence of acquired webs is unknown. Esophageal webs are twice as common in women as in men , with symptoms occurring more commonly in women than in men. Acquired esophageal webs have been reported in association with gastroesophageal reflux disease and iron-deficiency anemia as in Plummer-Vinson syndrome or Paterson-Kelly syndrome. Others include their association with dermatologic or systemic diseases, such as pemphigus vulgaris , epidermolysis bullosa , bullous pemphigoid , and desquamative esophagitis in chronic graft-versus-host disease .

Esophageal rings are usually seen in the lower third of the esophagus. There are two types; A (muscular ring) and B (mucosal ring or Schatzki). Muscular rings are rare and seldom cause dysphagia. They are frequently seen in children undergoing barium study for other reasons. They are located within 2 cm of the squamocolumnar junction and are due to muscular hypertrophy. In contrast, Schatzki’s ring is located at the squamocolumnar junction. The upper part is covered with squamous- and the lower part with columnar epithelium. The ring is a thin (<4 mm in axial length) smooth mucosa tissue. It is seen in 6% to 14% of asymptomatic patients during routine barium studies . Schatzki’s ring is seen in a quarter of patients with esophageal dysphagia and may be seen in association with patients who have eosinophilic esophagitis . It is more common in older patients (>40 years) but can also be seen in younger patients. The etiology of esophageal rings is unclear. There are inconclusive evidences implicating gastro esophageal reflux disease (GERD) in the pathogenesis of Schatzki’s rings .

Patients with esophageal web and Schatzki’s ring present with episodic solid food dysphagia. This frequently occurs after rapid ingestion of a bolus and when luminal diameter is less than 13 mm. In addition, patients with post-cricoid web may have nasopharyngeal reflux and/or aspiration. The dysphagia is transient, and if the bolus passes, the rest of the meal can be consumed without incident. However, some patients may present with acute bolus impaction. Physical examination may reveal features of associated medical conditions, such as bullous skin lesions and koilonychia in patients with webs. Diagnosis in both disorders is by barium swallow and/or esophagram and upper endoscopy.

Mechanical dilation is the treatment of choice for symptomatic patients. This can be accomplished by using a series of dilators over a guide wire (American dilators) or through scope balloon (controlled radial expansion [CRE]) dilators . Endoscopic incisions of recurring lower esophageal ring have also been reported . In patients with underlying medical conditions, such as eosinophilic esophagitis, GERD, dermatologic or chronic graft-versus-host disease, and iron-deficiency anemia, aggressive treatment of the underlying medical condition should be embarked on, before and after dilatation.

Peptic stricture

This complication is seen in 10% of patients with GERD. Peptic stricture is seen more commonly in patients of older age and male gender, with longstanding heartburn and chronic antacid use . It is associated with the presence of very low lower esophageal sphincter pressure, poor esophageal clearance due to poor motility, and the presence of large hiatal hernia. Other medical conditions that predispose to peptic stricture include scleroderma, post-Heller’s myotomy, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, Schatzki’s ring progressing to stricture, and prolonged nasogastric tube placement. The prevalence of peptic stricture has decreased markedly since the introduction of proton pump inhibitors . In addition to pyrosis, patients with peptic stricture present with progressive solid food dysphagia (when luminal diameter is less than 13 mm), with most meals leading to dietary modification (pureed, soft, or liquid) and eventually liquid dysphagia. Up to 25% of patients with peptic stricture do not have reflux- or GERD-associated symptoms, such as water brash, belching, globus sensation, chronic cough, hoarseness, and chest pain.

Upper endoscopy remains the gold standard for diagnosing erosive disease, stricture, and other complications such as Barrett’s esophagus and for therapeutic interventions such as dilatation. Peptic stricture usually occurs at the squamocolumnar junction, and is characterized by smooth narrowing that may be difficult to distend with air insufflation. Barium esophagram with barium-soaked marshmallow is complementary to upper endoscopy in patients with complex (tortuous and long stricture) or repeated strictures to reliably localize stricture, approximate length, and diameter of the stricture, in addition to ruling out epiphrenic diverticulum or paraesophageal hernia.

Esophageal peptic strictures are treated with esophageal dilatation, which can be accomplished by using mercury-filled bougies (Hurst or Maloney dilators) or over a guide-wire using either fluoroscopic or endoscopic guidance (Savary dilators) and balloon dilators passed through the endoscope and positioned within the stricture. Most endoscopists use the “rule of threes”: Pass no more than three dilators or balloon size at any given time to stretch the stricture. Usually, relief of dysphagia occurs when luminal diameter is greater than 15 mm (45 French). Perforation and bleeding occur post-esophageal dilatation in less than 0.5% of all procedures . Endoscopic placements of expandable plastic stent have also been used in recurrent benign severe peptic strictures . Aggressive therapy with proton pump inhibitors post-dilatation is mandatory, because this has been shown to improve dysphagia and decrease the need for subsequent esophageal dilatation .

Carcinoma: squamous cell cancer and adenocarcinoma

Esophageal cancer affects older age groups, with a peak incidence in patients between 60 and 70 years old and occurring more commonly in men (Male:Female = 4:1). Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma have similar clinical presentations despite different epidemiology. Worldwide, squamous cell cancer is the most common esophageal cancer. Squamous cell carcinoma is associated with tobacco and alcohol abuse, and is common in Asia, particularly in China, where the reported incidence is 131.8 cases per 100,000. In the United States, the reported incidence is 2.6 cases per 100,000. It is prevalent among African American males in the United States. In contrast, adenocarcinoma has a predilection for middle-aged Caucasian males and appears to be related to chronic GERD and underlying Barrett’s esophagus. The caveat to this is that 40% of patients with Barrett’s esophagus do not have symptoms of GERD. The mid esophagus is the most common site for squamous cell carcinoma whereas adenocarcinoma occurs commonly in the distal esophagus ( Fig. 3 ).