The overall prevalence of concussion is high school sports is unknown. In general, concussions in this age range occur much more frequently in games than in practice. Also for sports in which both sexes participate, reported concussion rates are higher for female than male high school athletes. Recent data show that the time required for return to play and resolution of symptoms is similar for women and men. Very little is known about the epidemiology of concussions in middle school–aged athletes and younger children.

Sports concussion

Estimates of the frequency of sports concussion are truly estimates. Before 2006, an often quoted number for total sports-related concussion in the United States was 300,000 per year. This number is based on data from 1991 National Health Interview Survey in which 46,700 households (120,000 persons) were interviewed, and, from these data, it was estimated that 1.54 million mild head injuries occurred in the year 1990 in the United States. Around 20% of these injuries occurred during sports or physical activity. To be counted as mild, the head injury had to involve loss of consciousness but did not have to be severe enough to cause death or long-term institutionalization. Estimates of sports concussion causing loss of consciousness range between 8% and 19.2%. Based on these data, Langlois and colleagues estimated sports concussion at 1.6 million to 3.8 million events per year in the United States. This is an estimate of all sports concussion in the United States and does not address any specific age group.

Youth sports concussion

On May 20, 2010 the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) gave testimony before the House Committee on Education and Labor regarding the occurrence of concussion in high school sports. The GAO believed that the “overall estimate of occurrence is not available.” Multiple definitions for concussion, poor recognition of this condition, and underreporting in the high school setting lead to the assumption that concussion is probably underestimated in youth sports.

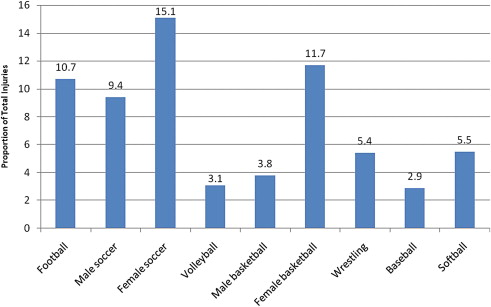

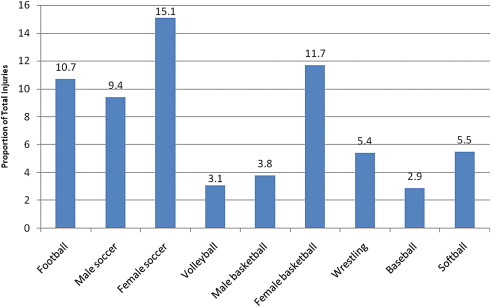

Yard and Comstock studied 100 high schools for more than 3 years and found 1308 concussions during 5,627,921 athletic exposures (AE). From this study, they estimated 395, 274 concussions per year in US high school athletes from 9 sports. There have been estimates that sport-related concussion accounts for approximately 9% of high school athletic injuries ( Fig. 1 ).

Youth sports concussion

On May 20, 2010 the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) gave testimony before the House Committee on Education and Labor regarding the occurrence of concussion in high school sports. The GAO believed that the “overall estimate of occurrence is not available.” Multiple definitions for concussion, poor recognition of this condition, and underreporting in the high school setting lead to the assumption that concussion is probably underestimated in youth sports.

Yard and Comstock studied 100 high schools for more than 3 years and found 1308 concussions during 5,627,921 athletic exposures (AE). From this study, they estimated 395, 274 concussions per year in US high school athletes from 9 sports. There have been estimates that sport-related concussion accounts for approximately 9% of high school athletic injuries ( Fig. 1 ).

General considerations

It is well documented that high school athletes with concussions take longer to recover than collegiate and adult athletes.

Adults and professional athletes usually recover relatively quickly from concussion with cognitive testing returning to baseline within 3 to 5 days of initial injury. College athletes show an average recovery time of 5 to 7 days. High school athletes take even longer to heal, with average recovery times of 10 to 14 days.

Concussions in high school sports occur much more frequently in games than during practice. The only sport that shows a higher concussion rate in practice than competition is cheerleading. Also, for sports in which both sexes participate, reported concussion rates are higher for female than male high school athletes. Recent data show that the time required for return to play and resolution of symptoms is similar for girls and boys.

Very little is known about the epidemiology of concussions in middle school–aged athletes and younger children. An emergency department (ED) surveillance study from2001 to 2005 estimated 253,000 ED visits for sports concussion for the age range 8 to 19 years. Around 40% (approximately 102,000 visits) were in the age range 8 to 13 years, and the remaining 60% (151,000) were in the 14- to 19-year range. In those aged 8 to 13 years, 25% (25,400 visits) were related to organized team sports (football, hockey, soccer, baseball, and basketball) and 75% (76,600 visits) with leisure and individual sports (bicycling, skiing, equestrian, sledding, playground).

Selected youth sports

All numbers mentioned later are for the United States (unless otherwise specified).

Concussion incidence studies are often published using a rate of injury per occurrence per 1000 athletic exposures (AE). AE are defined as an athletes’ participation in a single practice or competition. To give a rough estimate, 15 athletes playing in a game or practicing 5 days per week for 3 months (13 weeks) gives 975 AE. Thus, a rate of 0.5 injuries per 1000 AE requires an injury to 1 out of 30 athletes playing games or practicing for about 13 weeks. Table 1 shows the number of concussions per 1000 AE in high school based on sport, gender, and overall.

| Sport | Gessel et al, 2007 | Lincoln et al, 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Concussion Rate (per 1000 AE) | Concussion Rate (per 1000 AE) | |

| Baseball | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Softball | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| Boys’ Basketball | 0.07 | 0.1 |

| Girls’ Basketball | 0.21 | 0.16 |

| Boys’ Soccer | 0.22 | 0.17 |

| Girls’ Soccer | 0.36 | 0.35 |

| Football | 0.47 | 0.6 |

| Wrestling | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| All Boys | NR | 0.34 |

| All Girls | NR | 0.13 |

| All Athletes | NR | 0.24 |

Baseball and Softball

Baseball and softball are 2 of the most popular sports in the United States involving millions of athletes. Many participants are youth recreational athletes, with an estimated 1.7 million athletes per year. Approximately 450,000 boys participate in high school baseball, and 313,000 girls participate in high school softball, annually.

Overall, there has been a decrease in the number of baseball- and softball-related injuries in the past few decades but an increase in the severity of injuries, especially involving the head and face region. Powell and Barber-Foss’ studies of injury patterns in high school sports from 1996 to 1997 reported 1.5 to 2.8 baseball-related injuries per 1000 AE and 1.6 to 3.5 softball-related injures per 1000 AE. The investigators reported 0.23 concussions per season for every 100 athletes. During the 2005 to 2006 season, Rechel and colleagues’ study of high school sports reported 1.77 baseball-related injuries per 1000 AE during games and 0.87 injuries per 1000 AE during practice. Of these injuries, there were 0.08 concussions per 1000 AE during games and 0.03 concussions per 1000 AE during practices. The investigators reported 1.79 softball-related injuries during games and 0.79 injuries per 1000 AE during practices. Of these injuries, there were 0.04 concussions per 1000 AE during games and 0.09 concussions per 1000 AE during practices. Collins and Comstock analyzed high school baseball injury rates (2005–2007), reporting an overall injury rate of 1.26 injuries per 1000 AE, with a higher injury rate during competition (1.89 per athlete practices) versus practice (0.85 per athlete practices). Among all body regions, head and face injuries accounted for 12.3% of all injuries. Of these head and face injuries, concussions (28.7%) occurred as frequently as fractures (28.7%). Concussion involved only 3.5% of the overall diagnoses but represented an injury rate of 0.11 injuries per 1000 AE. Gessel’s study of 100 US high schools during the 2005 to 2006 season reported similar concussion rates between baseball (0.07 per 1000 AE) and softball (0.05 per 1000 AE) but a greater portion of total injuries in softball (5.5%) than baseball players (2.9%).

The most common mechanisms of injury relating to concussions in baseball or softball occurred from contact between a player and a ball, bat, or base. Collins’ study of high school baseball players reports that concussions were more likely to occur from being hit by a batted ball (8%) than other mechanisms of injury (2.9%), although this was not statistically significant. Gessel and colleagues’ study of high school athletes noted that baseball players compared with softball players were more likely to experience a concussion from contact with a ball (91.4% vs 59.1%) and to be associated with being hit by a pitch (50.6% vs 6.9%). Injuries varied depending on the specific player positions, with head and face injuries most likely to occur in batters (19.7%), outfielders (16.8%), and infielders (15%). Concussions were slightly higher in batters (4.6%) and outfielders (4.1%) than in catchers (3.6%), infielders (3.5%), and pitchers (3.3%). Base runners were the least likely to experience any of the various injuries.

Studies of baseball and softball players have revealed interesting findings regarding the rate of symptom recovery and return to play. Symptom resolution (ie, <6 days) seems to occur earlier in softball players than in baseball players (68.8% vs 64.2%; injury). However, a greater percentage of baseball players return to play within 6 days than softball players (52.9% vs 15.5%; injury). Fortunately, in both baseball players and softball players, more than 90% return to play within 10 to 21 days.

Severe and catastrophic youth baseball-related injuries are quite rare. Lawson and colleagues’ study of baseball-related injuries in children presenting to the EDs in the United States from 1994 to 2006 reported that 5.8% of all injuries were caused by concussions and closed head injuries. Only 3 cases were identified to be fatal injuries over the study period. The most common mechanism of injury was being struck by a baseball (46%) or being hit by the bat (24.9%). Athletes aged 12 to 17 years had the highest injury rate (19.8 per 1000 athletes) compared with younger athletes aged 6 to 11 years (12.1 per 1000 athletes). Boden and colleagues’ study of the incidence of catastrophic baseball-related injuries between 1981 and 2002 reported 33 catastrophic injuries in high school athletes, with 65% relating to severe head injuries. The overall direct catastrophic injury rate was 0.37 per 100,000 high school baseball players. The most common mechanism of injury was between a player and a ball involving a pitcher being struck in the head by a batted ball (56%) compared with a fielder (8%) or a batter (4%) being hit by a pitched ball. In most of these cases involving pitchers, the batter was using an aluminum bat.

Basketball

Basketball is the most popular female high school sport, with 448,450 athletes in 2008, and the second most popular male high school sport, with 552,935 athletes.

A 2006 study showed that girls had a higher rate of concussion (0.21 concussions per 1000 AE) than boys (0.07 concussions per 1000 AE). The difference is found almost exclusively in games. Both boys and girls have a rate of 0.06 concussions per 1000 AE in practice. In games, the concussion rate in boys roughly doubles to 0.11, whereas in girls the concussion rate increases 10-fold to 0.60. The same study reported concussions representing 11.7% of total injuries in girls and only 3.8% in boys. Girls were most likely to suffer injury while defending another player and with ball handling/dribbling. Boys were more likely to suffer head injury while chasing down loose balls and rebounding and due to contact with the playing surface.

An 11-year study from 1997 to 2008 showed boys’ basketball with a rate of 0.10 concussions per 1000 AE and girls’ basketball with a higher rate of 0.16. The concussion rate increased for both boys and girls over the evaluation period.

Catastrophic head injury in basketball

From 1982 to 1999, there was 1 reported fatality in high school basketball, 0 injuries resulting in permanent disability, and 4 serious head injuries that resolved without permanent sequelae.

Cheerleading

There is an increase in participation in cheerleading, with Daneshvar and colleagues reporting that the number of athletes has increased 18% overall since 1990. At present, there are an estimated 3.5 million participants within the United States. This includes 22,900 estimated participants (in 2002) between the ages of 5 and 18 years. Shields and Smith report that a 110% increase in participation has been seen for this age group since 1990 (10,900 participants compared with 22,900 participants in 2002). The investigators report that one of the leading causes in participant increase is also responsible for the rising prevalence of concussion: the maneuvers performed by the teams have become more difficult and more gymnasticslike. Daneshvar and colleagues indicate a significant increase in injury between 1980 and 2007, with 4954 ED visits in 1980 jumping to 26,786 ED visits in 2007. The investigators cite tumbling rings, pyramids, lifts, catches, and tosses as moves that have increased injury. The flier is particularly at risk as are those in the bottom quintile for body mass index.

Apart from the gymnastics element, concussion may also be the result of collisions with other cheerleaders. Cheerleading is one of the only sports to show a higher rate of concussion in practice than games (11.32 concussions per 1000 AE vs 3.38 concussions per 1000 AE). Daneshvar and colleagues found supporting evidence, reporting 82% of injury to occur during practice rather than game exposures. Schultz and colleagues found a rate of 9.36 head injuries per 1000 AE, whereas Shields and colleagues found a head injury rate of 5.7% among high school participants.

Football

In 2008, there were 1,100,000 high school football athletes and approximately 400,000 junior high school and junior football athletes. Football consistently shows the highest rate of concussion for all youth sports. A 3-year prospective study (1995–1997) found an incidence of 5.1% per season. About 14.7% of these players suffered a second concussion during the same season.

Data from a year-long study in 2006 showed a rate of 0.47 per 1000 AE. On defense, linebackers were shown to have the highest rate of concussion (40.9%). On offense, no significant difference was noted by position. The highest proportion of concussion occurs during running plays and resulted from contact with another player. Concussions were 7 times more likely to happen in games than practice (1.55 vs 0.21 per 1000 AE). A 2011 study showed that high school football reported a concussion rate of 0.60 per 1000 AE over an 11-year period from 1997 to 2008. The study also found an increase in concussion rate of 8% per year.

A 2004 retrospective survey study of concussion found that many high school football players underreported concussion. The study estimated that 15% of high school players suffered a concussion each season and 47.2% did not report having a concussion.

Catastrophic head injuries

Over a 13-year period (1989–2002), there were 92 catastrophic head injuries associated with high school football. During this same period, there were only 2 incidents at the college level. This averages to 7.23 events per year in high school and college sports. Of the total 94 head injuries, there were 8 (8.9%) fatalities, 46 injuries (51.1%) that left permanent neurologic damage and, 36 injuries (40%) that recovered completely. Of the patients whose past history was obtainable, 59.3% reported having a previous head injury before the day of the catastrophic event, and 38.9% of the respondents reported playing with residual neurologic symptoms from a previous head injury. High school sports in 2008 were associated with 43 direct catastrophic injuries, and all were associated with football. These injuries included 7 fatalities, 20 injuries that resulted in permanent disability, and 16 injuries that were considered serious but showed complete recovery. Of the 7 fatalities, 5 were related to head injury. Listed causes of death included subdural hematoma, brain injury, and second impact syndrome. This was the highest rate of injury since data collection began in 1982.

Ice Hockey

Ice hockey has an estimated 530,000 players in the United States, a number that includes 370,458 youth participants. Daneshvar and colleagues report that 27,800 men and 2800 women compete in the sport each year. Checking, hit contact allowed in ice hockey, begins at very young ages, sometimes as early as 9 years, and is often cited for the high volume of injuries as well as the elevated rate of concussions observed when compared with other sports. It is speculated that the youth are not given proper instructions on body checking and therefore are more likely to injure other players.

Hostetler and colleagues found that traumatic brain injury (TBI) rates decreased with age, which may be because of better playing techniques. Daneshvar and colleagues, however, reported the opposite, indicating in their article that recent studies have shown that players in the Bantam (aged 13–14 years) and Pee Wee (aged 12–13 years) groups had an increased risk of concussion compared with the Atom (aged 9–10 years) group. The investigators suggest the start of body checking as the reason for the increase in concussion observation. In players younger than 18 years, Hostetler and colleagues found that TBI accounted for 14.1% of all ice hockey–related injuries, whereas Hagel and colleagues found concussion to account for 6.4% of injuries at the Atom (aged 10–11 years) level and 12.6% at the Pee Wee (aged 12–13 years) level. Daneshvar and colleagues reported that concussions account for 6.3% of injuries occurring during practice exposures, and 10.3% of injuries during the game. Echlin and colleagues report an overall incidence of 21.52 concussions per 1000 AE. Johnson indicated that 25.3% of youth players received at least 1 concussion during the course of 1 season. Echlin and colleagues reported that after return to play from a concussion, 97% of recurrence of injury occurs within 10 days of the initial injury and 75% occur within 7 days. This increased susceptibility suggests that players may be returning to play too quickly.

Previous studies suggest that eliminating body checking from youth leagues may be the best way to prevent head injuries in this athlete population. Echlin and colleagues report that 24% of concussions followed a fight and that most concussions followed some form of a hit to the head. Preventing this hit may also provide a way to decrease concussion incidence. In Canada, Johnson indicates that the only junior league that continues to see an increase in players is in Quebec because they do not allow body checking until the Bantam level (ages, 14–15 years). The rest of the country is experiencing a decrease in participation. Hagel and colleagues and Daneshvar and colleagues both report that leagues that permit body checking are associated with a significantly higher occurrence of concussion.

Lacrosse

Lacrosse is one of the fastest growing sports in the United States. Most collegiate teams are located in the East Coast region, but there has been an expansion of teams toward the West Coast region. It is estimated that 33,000 male and 22,000 female high school athletes participate in lacrosse any given year. Despite the increasing level of participation, there are very few studies assessing the impact of concussions in lacrosse athletes at the high school level.

The few studies of high school lacrosse athletes suggest a greater number of concussions in boys versus girls. Lincoln and colleagues studied head and neck injuries in 507,000 high school lacrosse athletes (both boys and girls) over 4 seasons (2000–2003). Concussions represented a higher percentage of injuries among boys (73%) than among girls (40%). Concussion rates were 0.28 per 1000 AE for boys versus 0.21 per 1000 AE for girls. These findings were similar to concussion rates in collegiate athletes (0.26 per 1000 AE in men [95% confidence interval (CI) 5, 0.23–0.39]; 0.25 per 1000 AE in women [95% CI 5, 0.22–0.28]) from 1988 through 2004. In a similar study, Lincoln examined the incidence and relative risk of concussions in 12 high school boys’ and girls’ sports from 1997 to 2008. Concussions represented 9.2% (boys) and 4.3% (girls) of all injuries during the study period. Concussion rates were 0.3 per 1000 AE (CI 5.5, 4.9–6.3) for boys and 0.20 per 1000 AE (CI 3.5, 2.9–4.2) for girls. The investigators reported a mean annual increase in concussions per year of 17% and 14% for boys and girls, respectively. The main injury mechanism for boys was player-to-player contact, whereas for girls it was stick or ball contact. These findings differed from collegiate lacrosse, in which 78.4% of men’s concussions resulted from a collision with another person, whereas 10.4% resulted from collision with a stick. More than half the time, the concussions in female collegiate lacrosse players resulted from contact with a stick. The difference in mechanisms of injury between boys and girls most likely reflects differences in the games relating to protective equipment (boys use helmets, whereas girls do not) rules and level of contact permitted (greater in boys). There have been no reported catastrophic injuries relating to concussions in high school lacrosse players over the past 2 decades.

Soccer

Participation in soccer has grown over the past few decades. In the United States, an estimated 13 to 15 million youth athletes participate in soccer at the recreational to elite levels. Almost 3.2 million participate in the US Youth Soccer Association, representing athletes younger than 19 years. From 2009 to 2010, more than 745,000 boys and girls participated in high school soccer, making it the fifth most popular sport in the United States. However, with increased participation has come a potential increase in the number of concussions.

Overall, there seems to be an increase in the number of concussions reported by soccer athletes over the past few decades. However, there are conflicting data regarding the differences in the rate of concussions between young boy and girl soccer athletes. An earlier study from 1990 to 2003 revealed an estimated 1.9% of pediatric (ages, 2–18 years) soccer-related injuries presenting to the ED were caused by concussions. A 2005 to 2006 study of US high school soccer athletes revealed an overall rate of 0.22 concussions per 1000 AE in boys compared with 0.36 concussions per 1000 AE in girls. Both were more likely to sustain a concussion during games (girls, 0.97 per 1000 AE; boys, 0.59 per 1000 AE) than practices (girls, 0.09 per 1000 AE; boys, 0.04 per 1000 AE). A study of high school soccer athletes from 2005 to 2007 revealed that boys and girls sustained a similar rate of concussions (9.3% and 12.2%, respectively) (injury proportion ratio [IPR], 1.31; 95% CI, 0.91–1.88) but at a higher rate than what was previously reported. Similar to other studies, the investigators did report a greater rate of concussions occurring during games versus practices (IPR, 3.25; 95% CI, 1.99–5.31). A study of recurrent injuries in high school soccer athletes revealed a similar rate of concussions in boys versus girls (9.2% vs 10.6%) but a higher reinjury rate in girls than in boys (19.1% vs 13.8%). Whether girls truly have a higher risk of sustaining a concussion is not exactly clear. Factors contributing to the perceived increased rate could include a greater awareness of concussions or greater propensity to report concussive symptoms.

The most common mechanisms of injury relating to concussions in soccer players involve head-to-head collisions, contact with the ground, or contact with the ball. Several studies have shown that soccer players were most likely to sustain a concussion from a head-to-head collision while attempting to head the ball. In a study by Gessel and colleagues, boys were more likely than girls to experience concussion via this mechanism (40.5% in boys vs 36.7% in girls [IPR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.45–1.48; P <.01]). Girls were more likely to sustain a concussion from contact with the ground (22.6% vs 6.0% [IPR, 3.77; 95% CI, 3.56–4.00; P <.01]) and contact with the soccer ball (18.3% vs 8.2% [IPR, 3.68; 95% CI, 3.45–3.92; P <.01]). Similarly, Yard’s study reported that 71.8% of athletes experienced concussions from a head-to-head collision. Athletes were less likely to sustain a concussion from contact with the ground (16.1%) or contact with the ball only (7%). The investigators noted that illegal activity contributed to 25.3% of concussions (IPR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.16–3.16) compared with injuries caused by legal activities. Injuries were more likely to occur to goalkeepers (21.7%) than to players in other positions (11.1%) (IPR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.92–2.00; P <.01).

Studies of time loss and return to play reveal that most concussions in soccer players among high school athletes require several days to a couple of weeks to resolve. A recent study of high school athletes suggests that 46.1% require approximately 7 to 21 days to recover, followed by 38.9% requiring less than 7 days to recover. Severe injuries were much less common, with 11% of boys and 7.4% of girls experiencing a concussion lasting longer than 3 weeks. In this study, 7.3% of concussions were season ending. Despite several published return-to-play guidelines, Yard and Comstock revealed noncompliance with the Prague return-to-play guidelines ranging from 15% to 19% for boy and girl high school soccer players.

Despite the potential for head-to-head collisions in youth soccer, catastrophic events are exceedingly rare. Longitudinal studies have reported 17 to 28 catastrophic head and neck injuries from participation in youth soccer between 1982 and 2008. Reported direct injuries per 100,000 athletes were 0.1 (fatal), 0.03 (permanent neurologic deficits), and 0.08 (serious injury with complete recovery) for youth boys and 0 (fatal), 0.02 (permanent neurologic deficits), and 0.02 (serious injury with complete recovery) for youth girls. A good number of these injuries related to goal posts falling onto the youth soccer athlete. Several recommendations including keeping soccer goals anchored, never allowing children to hang or climb soccer goals, removing the soccer goals when not in use, and periodic maintenance have led to a significant decrease in these fatalities.

Wrestling

A total of 259,688 boys were involved in wrestling in high school in 2008. Female wrestling is also on the increase, with approximately 1700 female athletes.

A 2006 study showed a concussion rate of 0.18 concussions per 1000 AE with 3 times the rate in competition than practice (0.32 and 0.13, respectively). Over 11 years, Lincoln and colleagues found a similar rate of 0.17. This rate was increasing over time at a rate of 27% per year.

Takedowns were the most common maneuver or activity associated with concussion (42.6%). Contact with another person (60.1%) was the major cause of concussion as opposed to contact with the playing surface (26.9%). Catastrophic head injury is very low; from 1982 to 1999, there were 1 fatality in high school wrestling and no injuries with permanent disability.

These authors have nothing to disclose.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree