Individuals experience multiple changes as a result of amputation. These changes not only are physical in nature but also may include psychological, financial, and comfort changes across the spectrum of an individual’s life. It is important to assess the emotional responses that an individual may experience postsurgery and throughout the rehabilitation process. Grieving is a natural and normal emotional response postamputation. Grief resolution is one of the primary areas of focus in counseling amputees. This article examines various factors and strategies used in the adaptation and recovery from amputation.

Key points

- •

Individuals experience multiple changes as a result of amputation. These changes not only are physical in nature (body image and functional abilities) but also may include psychological, financial, and comfort changes across the spectrum of an individual’s life.

- •

It is important to assess the emotional responses that an individual may experience postsurgery and throughout the rehabilitation process. Grieving is a natural and normal emotional response that all amputees experience postamputation. Grief resolution is one of the primary areas of focus in counseling amputees.

- •

The development of effective coping strategies aids in the physical and emotional functional well-being of an amputee. Some of the more common strategies include relaxation training, use of exercise, maintaining a balanced diet, identifying and addressing negative self-talk, pacing, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), frequently used to treat posttraumatic stress syndromes.

- •

In the effective treatment of individuals with amputation, it is imperative to assess the emotional adjustments of individuals to change. This article examines various factors and strategies used in the adaptation and recovery from amputation.

When treating amputees, it is essential that medical professionals recognize not only the physical changes that amputation represents but also a series of other social, emotional, psychological, and economic issues that have an impact on a patient’s rehabilitation.

Changes imposed by amputation

There are several reasons for loss of limb, or amputation. Amputation may be congenital or due to tumor, trauma, disease, and/or infection. It may occur without any notice, immediately after an accident. It may be a necessary part of medical treatment or performed to increase functionality. Regardless of the cause, amputation imposes several changes. Just as individuals are unique, so are their responses to and experiences resulting from amputation: physical changes as well as emotional and psychological. Treatment must address and involve all three of these areas in order to obtain a positive outcome.

Changes in Body Image

Significant body image changes occur. Except for cases of congenital anomaly, humans are born with two arms and two legs. Looking at a mirror, individuals are used to seeing themselves in a certain way; clothes fit in a familiar manner; there is symmetry and balance to the human body. Someone who experiences amputation may feel incomplete, no longer whole. For some, loss of any body part, even a finger or toe, may be perceived as a gross disfigurement. Individuals may no longer feel attractive by societal standards.

Changes in Functional Abilities

Young children learn to roll over, crawl, stand, and walk. They learn to grasp objects and use their arms and hands for everyday activities. Using limbs and digits becomes second nature. They do not analyze how to break down muscle movement in order to complete everyday tasks. All of this changes postamputation. Necessary adaptations include learning to use muscles and limbs/digits in different manners, building up different muscles, using adaptive equipment and/or modifications, and using prostheses or learning new techniques to complete activities. Additional time is required, at least initially, to complete tasks. Adjusting is a frustrating process that requires assistance (therapists, aides, and family members) immediately after amputation. With time, practice, and the development of new techniques to accomplish various tasks, the ease of completing them should rapidly increase. It is also important for amputees to confront that there may be some tasks they never will be able to complete.

Changes in Finances

Amputation frequently has an impact on individual and family finances. If injured at work, individuals may receive long-term and short-term disability payments, usually a percentage of their previous income. Additionally, many find they are unable to work in their established field or even find employment, especially in an already tight job market.

Medical insurance coverage is another area that can have an impact on finances negatively. Certain insurance policies have yearly deductibles in addition to copayments for services, such as hospitalization, physician care, medical procedures, medications, equipment, and follow-up therapy, many of which frequently require preauthorization. Care and services may be delayed or denied by an insurance company, causing additional patient stress and frustration.

Medicare is a federal program that provides medical insurance to those who are 65 years of age and older or who are deemed disabled. To qualify, an individual (or spouse) must have worked at least 30 quarterly hours and paid into the Medicare system. To qualify for Medicare before age 65, someone must be deemed disabled and qualify for Social Security disability income (SSDI). The process to become eligible for SSDI benefits is long, tedious, and frustrating. It is not uncommon for an individual to be denied SSDI benefits 2 or 3 times, and legal assistance may be required to appeal eligibility denials. Once approved for SSDI benefits, there is a 2-year waiting period (from the date of eligibility determination), before Medicare benefits become active. Once approved for SSDI and Medicare, issues of copayments for services remain. In the meantime, there may be little household income, and patients may find themselves without insurance.

For those without medical insurance or who are underinsured, the cost of amputation and related services can create insurmountable debt. Those without insurance may qualify for state-assisted medical care (Medicaid), but there frequently are wait lists for these programs. Just as with most insurance programs, Medicaid also requires copayments for services.

The overall consequences associated with changes in income resulting from amputation can be devastating. With a loss of income, individuals prioritize their monthly bills. They may have to forgo paying for medications to cover rent/mortgage. If they cannot pay the rent/mortgage, they need to find affordable housing and move. Some cash out retirement/savings accounts, stocks/bonds, and their children’s college funds to pay the mounting medical bills; many file for bankruptcy.

Changes in Comfort

There are many emotional and physical changes associated with adaptation to amputation. While trying to adapt to their situation, it is common for amputees to isolate themselves from family and friends. Their interactions with others may become stilted or awkward as both sides try to muddle through the situation and interact as if there are no changes. As a result of financial changes, such as those discussed previously, amputees may find that they have to change their lifestyle, because they are financially unable to participate in various activities (eg, going out to dinner or the movies).

Some experience pain after amputation, which may be physical and/or neuropathic in nature. To alleviate pain, medications may be prescribed. Medications may help resolve pain but also carry with them side effects that may affect an individual’s comfort levels (personality changes from medications, changes in bowel/bladder, sexual functioning, and so forth).

When people experience physical, emotional, and psychological changes, changes occur to their homeostatic environments; they frequently experience anxiety, depression, or a mix of both emotions. These emotional responses are discussed further.

Changes imposed by amputation

There are several reasons for loss of limb, or amputation. Amputation may be congenital or due to tumor, trauma, disease, and/or infection. It may occur without any notice, immediately after an accident. It may be a necessary part of medical treatment or performed to increase functionality. Regardless of the cause, amputation imposes several changes. Just as individuals are unique, so are their responses to and experiences resulting from amputation: physical changes as well as emotional and psychological. Treatment must address and involve all three of these areas in order to obtain a positive outcome.

Changes in Body Image

Significant body image changes occur. Except for cases of congenital anomaly, humans are born with two arms and two legs. Looking at a mirror, individuals are used to seeing themselves in a certain way; clothes fit in a familiar manner; there is symmetry and balance to the human body. Someone who experiences amputation may feel incomplete, no longer whole. For some, loss of any body part, even a finger or toe, may be perceived as a gross disfigurement. Individuals may no longer feel attractive by societal standards.

Changes in Functional Abilities

Young children learn to roll over, crawl, stand, and walk. They learn to grasp objects and use their arms and hands for everyday activities. Using limbs and digits becomes second nature. They do not analyze how to break down muscle movement in order to complete everyday tasks. All of this changes postamputation. Necessary adaptations include learning to use muscles and limbs/digits in different manners, building up different muscles, using adaptive equipment and/or modifications, and using prostheses or learning new techniques to complete activities. Additional time is required, at least initially, to complete tasks. Adjusting is a frustrating process that requires assistance (therapists, aides, and family members) immediately after amputation. With time, practice, and the development of new techniques to accomplish various tasks, the ease of completing them should rapidly increase. It is also important for amputees to confront that there may be some tasks they never will be able to complete.

Changes in Finances

Amputation frequently has an impact on individual and family finances. If injured at work, individuals may receive long-term and short-term disability payments, usually a percentage of their previous income. Additionally, many find they are unable to work in their established field or even find employment, especially in an already tight job market.

Medical insurance coverage is another area that can have an impact on finances negatively. Certain insurance policies have yearly deductibles in addition to copayments for services, such as hospitalization, physician care, medical procedures, medications, equipment, and follow-up therapy, many of which frequently require preauthorization. Care and services may be delayed or denied by an insurance company, causing additional patient stress and frustration.

Medicare is a federal program that provides medical insurance to those who are 65 years of age and older or who are deemed disabled. To qualify, an individual (or spouse) must have worked at least 30 quarterly hours and paid into the Medicare system. To qualify for Medicare before age 65, someone must be deemed disabled and qualify for Social Security disability income (SSDI). The process to become eligible for SSDI benefits is long, tedious, and frustrating. It is not uncommon for an individual to be denied SSDI benefits 2 or 3 times, and legal assistance may be required to appeal eligibility denials. Once approved for SSDI benefits, there is a 2-year waiting period (from the date of eligibility determination), before Medicare benefits become active. Once approved for SSDI and Medicare, issues of copayments for services remain. In the meantime, there may be little household income, and patients may find themselves without insurance.

For those without medical insurance or who are underinsured, the cost of amputation and related services can create insurmountable debt. Those without insurance may qualify for state-assisted medical care (Medicaid), but there frequently are wait lists for these programs. Just as with most insurance programs, Medicaid also requires copayments for services.

The overall consequences associated with changes in income resulting from amputation can be devastating. With a loss of income, individuals prioritize their monthly bills. They may have to forgo paying for medications to cover rent/mortgage. If they cannot pay the rent/mortgage, they need to find affordable housing and move. Some cash out retirement/savings accounts, stocks/bonds, and their children’s college funds to pay the mounting medical bills; many file for bankruptcy.

Changes in Comfort

There are many emotional and physical changes associated with adaptation to amputation. While trying to adapt to their situation, it is common for amputees to isolate themselves from family and friends. Their interactions with others may become stilted or awkward as both sides try to muddle through the situation and interact as if there are no changes. As a result of financial changes, such as those discussed previously, amputees may find that they have to change their lifestyle, because they are financially unable to participate in various activities (eg, going out to dinner or the movies).

Some experience pain after amputation, which may be physical and/or neuropathic in nature. To alleviate pain, medications may be prescribed. Medications may help resolve pain but also carry with them side effects that may affect an individual’s comfort levels (personality changes from medications, changes in bowel/bladder, sexual functioning, and so forth).

When people experience physical, emotional, and psychological changes, changes occur to their homeostatic environments; they frequently experience anxiety, depression, or a mix of both emotions. These emotional responses are discussed further.

Emotional reactions to limb loss

The loss of a limb is similar to other major losses in life, especially what is near and dear. In its intensity and degree of impact, the loss of a limb probably comes closest, however, to the experience most encounter when losing a loved one. Just as it is natural to grieve the death of someone loved, amputees must grieve the loss of their limb, body integrity, and the people they used to be. Moreover, patients feel a loss of control over the limb loss process and their medical care. The initial period after amputation can be stressful, during which emotions can be raw and intense and feel out of control. Many amputees are confused by these emotions and wonder if they are “going crazy.” It is best to warn new amputees of this possibility and let them know that grieving is a normal and natural process. They also should be encouraged to express and communicate their feelings to others, without trying to block or impede them. This likely makes it easier for them to accept and adapt to their amputation.

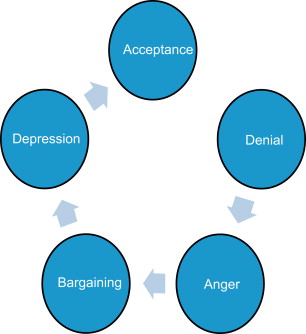

Kübler-Ross was the first to identify and delineate the stages or steps that are gone through emotionally when faced with impending death or that of a loved one. She believed that each stage is proceeded through sequentially until reaching the final stage of acceptance. Fig. 1 shows how she viewed individuals progressing through the stages of loss.

Dr. Kubler-Ross made a tremendous contribution to the field by acknowledging the importance of grieving and acceptance around death and dying. Her sequential model is probably too rigid to apply to the emotional experiences amputees face. Rather than proceeding steadily through a series of prescribed stages toward the final stage of acceptance, observations have shown that amputees experience a range of emotional reactions that can change from one moment to the next. Emotions can go back and forth along the continuum toward acceptance. Sometimes individuals may become stuck in a particular stage and remain there for some time. Not everyone experiences all of the stages. Fig. 2 shows our view of how the grief process occurs.

Through this dynamic process, an adaptation to amputation eventually emerges. The important message to convey to amputees is that is natural to experience a wide variety of emotions, especially after a traumatic amputation. Those in the position to choose amputation may begin the grieving process from the moment they begin to contemplate it or as soon as they make their decision to have it. Others, like their peers who lost their limbs through trauma, wait until after amputation to process their feelings when faced with reality.

Many amputees find talking to a counselor beneficial in dealing with the grief and adjustments they face after an amputation. A Turkish proverb states, “He that conceals his grief finds no remedy for it.” This is why the authors encourage most of amputee patients to participate in individual counseling, group counseling, or both. Sharing and expressing their feelings to someone who is objective and removed from their normal social support network may ease the burden shouldered by family and friends who, like amputees, often experience distress and probably are in the throes of their own grief process. However much they want to help, family and friends are not trained professionals and may not know how to respond to an amputee’s particular emotional needs. A counselor can provide support, teach a variety of coping skills, and identify psychological obstacles that may be getting in the way.

Some of the typical emotional reactions amputees experience are discussed.

Shock and Disbelief

Typically, most amputees experience shock and disbelief after hearing they need an amputation or after amputation surgery itself. During this stage, most people find themselves confused, in disbelief, and unable to comprehend the magnitude and significance of what the amputation means for their lives from this point forward. It is common to feel dazed, as if in a dream or a nightmare. During this time, individuals may feel emotionally numb or as if they are just going through the motions. Others may find themselves tearful or even sobbing. Some experience sleeping problems, appetite loss, or loss of concentration or the ability to make even simple decisions. Those who become stuck in this stage usually have difficulty dealing with the hurdles typically encountered during rehabilitation due to their constant state of disbelief and disorientation, even over minor or trivial obstacles.

Denial

If shock and disbelief help block out the magnitude of what has happened and insulate amputees from overwhelming emotional pain, denial allows them to manage reality by not thinking about it or by minimizing the amputation’s impact on their lives. Patients in this stage may act as if the amputation is no big deal and believe that once they receive their prosthesis they will be able to function as they did before. In the extreme, patients may take on a Pollyanna attitude, that everything is good. They may appear overly cheerful and positive. Indeed, such individuals may be viewed as model patients because they are so positive. Yet the reason they respond this way is to deny or avoid facing the negative aspects of their disability. It is important that medical caregivers monitor patients in denial as closely as they do those who are more expressive of their emotions; delayed grief reactions may occur at any time. Patients may eventually verbalize their concerns to one member of their health care team and not the others, so it is important for such information to be conveyed to the other team members when it occurs. A referral to a mental health professional may be appropriate at this time.

Anger

As reality begins to sink in, denial may turn into anger and rage. It is common to repeatedly ask, “Why me?” Additional questions or self-statements often follow, such as, “This isn’t fair!” “How can this happen to me?” and “Who is to blame?” Anger can be experienced in several different forms, including frustration, annoyance, and irritation. Those who formerly were slow to lose their temper suddenly may find themselves with little patience and a short fuse. This stage is most pronounced for people who think that their amputations were a result of other people’s errors, neglect, or ineptitude. They resent those responsible for their limb loss. Others who have undergone an amputation after illness or disease may feel bitter that life is unfair or unjust to allow cancer or diabetes to take their limb. Sometimes people blame God for their problems; often they blame themselves, especially if they believe they had a part in causing the amputation to happen.

Our society is very conflicted about anger. Many individuals are raised or socialized to believe that having or expressing anger is bad and they need to avoid it at all costs, usually by keeping it inside. Repressing anger, however, may exact a heavy price; anger that is not expressed outwardly can turn inward and be channeled physically, causing stomach ulcers, pain, and other physical ailments. The repression of feelings can amplify residual limb pain or phantom pain. Moreover, amputees who avoid expressing their anger may become more irritable and easily strike out or snap at those closest to them, such as family members, friends, caregivers, or medical staff. Those who remain stuck in this stage tend to be indiscriminant when it comes to directing their anger toward others.

Depression

With depression, the question remains, “Why me?” But with depression, rather than feeling angry toward their circumstances, patients feel sorry for themselves. Freud once defined depression as “anger turned inward.” These patients typically feel victimized, hopeless, and helpless. Depression usually leads to fatigue, apathy, and loss of interest or pleasure in activities that used to be enjoyable. It is often difficult to concentrate and find the energy to do even the littlest things. Some may feel overly sad, melancholy, and tearful; others may feel detached and emotionally numb.

The following symptoms are consistent in many individuals diagnosed as depressed :

- 1.

Depressed mood most of the day nearly every day

- 2.

Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities most of the day

- 3.

Significant weight loss or weight gain

- 4.

Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day

- 5.

Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day

- 6.

Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day

- 7.

Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- 8.

Diminished ability to think or concentrate

- 9.

Recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt

The physical components of depression may be confusing. Amputees may interpret their symptoms of lethargy and fatigue as signs of their worsening physical health (eg, increased pain complaints). This may prompt pessimism about the future, which is likely to feed right back into their depression. As more depressed is felt, pain can increase and vice versa. This can lead to a vicious pain-depression cycle. Although the type of depression in this stage is usually situational, if an amputee also has a biologic depression (ie, a depressive predisposition that is inherited), the depression may become even more severe and prolonged.

Anxiety

Amputees may become nervous, anxious, or even panicked about their future life as an amputee. They may wonder, “What do I do now?” Some worry that their lives are over or that they have no future. The fear of the unknown is frightening. Some worry about rational threats or dangers the future may bring. Those who undergo amputation as a result of developing cancer in a limb may wonder if all the cancer was removed or their cancer will return in the future. They may catastrophize or worry about the worst things happening to them, such as eventually dying from cancer. Others fear they may not be able to work again, their finances will crumble, and their marriages will dissolve. Such worry can generate physical tension, causing shakiness, insomnia, panic attacks, and increased pain.

Those whose amputations were the result of traumatic events, such as car or work-related accidents or combat, may experience symptoms associated with anxiety and trauma. They may have nightmares or flashbacks of the trauma, often unpredictably. This is normal because it is the mind’s way of working through, or digesting, the trauma. Nightmares often occur because there is less control of thoughts and feelings while asleep; it is easier for the traumatic experiences and memories to leak into dreams. When anxiety and trauma become severe, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may develop. Symptoms of PTSD include

Intrusive memories

- •

Flashbacks, or reliving the traumatic event for minutes or even days at a time

- •

Upsetting dreams about the traumatic event

- •

Avoidance and emotional numbing

- •

Trying to avoid thinking or talking about the traumatic event

- •

Feeling emotionally numb

- •

Avoiding activities previously enjoyed

- •

Hopelessness about the future

- •

Memory problems

- •

Trouble concentrating

- •

Difficulty maintaining close relationships

- •

Anxiety and increased emotional arousal

- •

Irritability or anger

- •

Overwhelming guilt or shame

- •

Self-destructive behavior, such as drinking too much

- •

Trouble sleeping

- •

Being easily startled or frightened

- •

Hallucinations, such as hearing or seeing things that are not there

- •

Guilt

Guilt is an affective state in which people experience conflict at having done something that they believe they should not have done or, conversely, not having done something they believe they should have done. It gives rise to a feeling that does not go away easily, driven by conscience. Amputees may feel guilt and regret for what they perceive as their fault for causing their amputation. They may feel responsible for having caused the accident that took their limb or they may blame themselves for not taking care of themselves by eating too much, not exercising enough, working too hard, smoking, and so forth.

Guilt also may come from feeling bad about the losses and changes that occur after amputation. For example, individuals who used to be a primary breadwinner in the family may feel guilt because they no longer are able to support their family financially. They are heartbroken when watching their spouses go off to work while they stay home feeling helpless and useless, without much structure or direction in their lives. For many men, work often defines their character or sense of identity. When their work is stripped away, they may experience a major blow to their ego, which can be devastating to their self-esteem and self-worth. The hopes and dreams they may have had for themselves and their families no longer seem possible, and they may feel guilty for letting everybody down.

Bargaining

Bargaining may occur prior to loss as well as afterward. When faced with a life-threatening choice of either dying or losing a limb, most people opt to avoid death and choose amputation. Many cancer and diabetic patients make this choice every day. Others may not be faced with such clear-cut, life-and-death decisions. Some might choose amputation as a way to avoid pain or maintain function. In their minds, they are striking a bargain, “If I do this difficult thing, something good will come out of it.” In other words, “If I give up my limb, I won’t have to worry about dying.” Bargaining is a way of trying to gain control over an unfortunate situation—an attempt to interject logic and rationality into a situation that may seem perplexing, uncertain, and frightening. Some negotiate with a higher power, someone or something they perceive as having control over the situation. They may make promises to God in return for their amputation working out successfully and their lives being spared. Bargaining may lead to an easier acceptance of amputation because patients who have survived, and not died, may be better positioned to accept the terms of their grand bargain, namely accepting their amputee status.

Yearning

In a recent study, Zhang and colleagues found that most people’s primary negative feeling after a loss was not sadness or anger, as previously thought, but yearning. Individuals often deeply miss a loved one who has died, wishing they still were with them. Individuals may hold out hope, despite knowing intellectually that they are not coming back. Many find reassurance in their faith that someday, in the afterlife, they will meet their loved ones again. Prigerson says, “Grief is really about yearning and not sadness… That sense of heartache. It’s been called pangs of grief.” In a similar manner, yearning to have back a limb is common after amputation. A few patients have expressed belief that their limbs will grow back. Although technical features of prosthetics and what they can do have come a long way in recent years, they are still not full replacements for limbs. Patients begin to realize this as soon as they receive their artificial limbs and become aware of their limitations.

Amputees may yearn for the old days when they had all their all their limbs intact. They also may yearn for the way things were when they had gainful employment, were earning an income, had their health, and were able to do activities without thinking about it. It is typical for amputees to miss their former carefree selves who did not take a long time to dress and care for themselves the way they do as amputees.

Acceptance

Although Kübler-Ross believed that attaining acceptance was the final stage of grief, Zhang and colleagues found that acceptance was not the final stage but that it comes and goes throughout the grieving process. It was the most common feeling among those who were grieving and it often occurred early in the grieving process. For amputees, acceptance is often reflected in the adjustments, accommodations, and adaptations they begin to make from the moment they undergo amputation. One of the first adaptations required of leg amputees is using a wheelchair to get around while wearing a cast on the leg and then a removable cast (eg, clamshell). They may eventually switch to a walker and later use forearm crutches or a cane. Arm amputees, on the other hand, may have to learn how to use new eating utensils. Even prostheses require making adjustments in using muscles, coordination, and balance as well as the time and effort it takes to don and remove the prosthesis.

People are adaptable beings and have learned to adapt to some of the most inhospitable environments, including the frigid cold of Antarctica, the barren sand of the Sahara desert, and the weightless environs of outer space. Similarly, most amputees are able to go with the flow as they accept and deal with each step in the rehabilitation process. Through successful adaptation with each new step, amputees realize that they can go on with their lives if they are willing to be flexible and make accommodations to the way they previously did things. Consequently, they may start to experience more good days than bad ones. Anger and depression may subside, as amputees feel more confident about being able to move forward and realize they have a future. They begin to get back to participating in some of the pleasurable activities they used to do before amputation, albeit with adjustments, or learn new activities—such as skiing—while working around their physical limitations through the use of adaptable equipment, learning new skills, and applying new techniques. As amputees accept that they have to do things differently, they learn that their lives do not have to stop and that they can live their lives in a new but different way. As one amputee put it recently, “I accept my amputation, but I don’t have to like it.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree