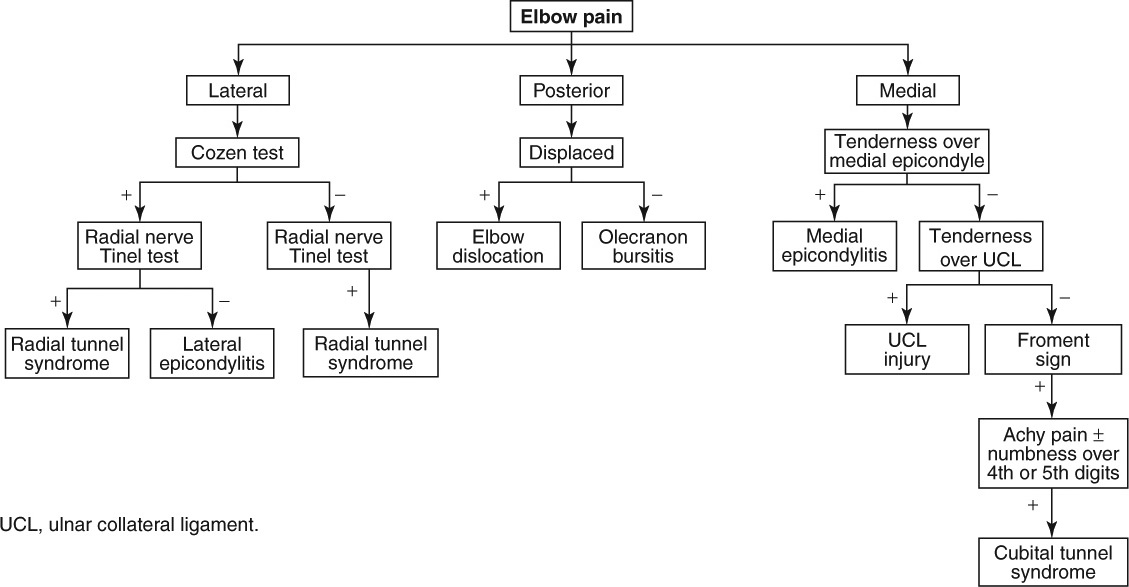

Elbow Pain

|

Red Flag Signs and Symptoms

Any of these signs and symptoms should prompt urgent evaluation and appropriate intervention:

Fevers

Chills

Hot, swollen joint

Progressive neurologic symptoms

Loss of pulses

LATERAL EPICONDYLITIS (TENNIS ELBOW)

Background

Despite the fact that many people who do not play tennis get this disorder, the term tennis elbow is still popularly used. Lateral epicondylitis itself turns out to be a misnomer because histologic studies reveal that tendinosis (fibrosis), not itis (inflammation) may be the underlying mechanism of the pathology. Nevertheless, the term lateral epicondylitis has persisted.

Overuse injuries with poor mechanics or ill-fitting equipment (inappropriate racket grip size, overly tight racket string tension, repetitive turning of a screwdriver) are contributing factors, as is a lack of muscle conditioning prior to these activities.

Clinical Presentation

Patients typically are 40 to 50 years of age and present with lateral elbow pain that occurs when performing activities such as lifting, shaking hands, or any other activity that

requires repetitive forearm pronation and supination. As the pathology progresses, patients may relate pain with minimal activities such as opening a door and holding utensils. Because of this pain-limiting function, patients sometimes complain of “weakness.”

requires repetitive forearm pronation and supination. As the pathology progresses, patients may relate pain with minimal activities such as opening a door and holding utensils. Because of this pain-limiting function, patients sometimes complain of “weakness.”

Physical Examination

Localized tenderness is identified slightly distal to the lateral epicondyle at the common extensor origin. Resisted wrist extension typically elicits pain (Mill test) (Fig. 3.1). Passive wrist flexion with the elbow in extension may also elicit the patient’s pain. Resisted extension of the third digit with the elbow in extension may also reproduce symptoms (although this can also be positive in radial tunnel syndrome). Resisted supination of the forearm is also typically painful. One way to test this is by shaking hands with the patient and applying a pronating force (making the patient supinate to resist).

Another good test is to stabilize the patient’s elbow and palpate the lateral epicondyle as the patient pronates and

extends the wrist against resistance (Cozen test) (Fig. 3.2). Reproduction of symptoms is characteristic of lateral epicondylitis. This test can be done with the elbow flexed or extended. It may be more sensitive when the elbow is extended.

extends the wrist against resistance (Cozen test) (Fig. 3.2). Reproduction of symptoms is characteristic of lateral epicondylitis. This test can be done with the elbow flexed or extended. It may be more sensitive when the elbow is extended.

Diagnostic Studies

Radiographs are not always obtained but may be ordered to rule out other pathologies such as a loose body, fracture, or arthritis.

Treatment

Initial treatment consists of decreasing the pain and inflammation (inflammation may not be the underlying cause, but it does appear to be a factor) and removing or modifying the offending activity.

Ice is a terrific anti-inflammatory agent in this superficial condition. Anti-inflammatory creams can also be beneficial. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be helpful.

An injection of anesthetic and corticosteroid (with care not to inject into the tendon) can be very helpful to speed recovery (Fig. 3.3). Sometimes the injection needs to be repeated (but should not be performed more than three times).

LATERAL EPICONDYLITIS INJECTION

After informed consent is obtained, identify the lateral epicondyle. The authors favor using a 25-gauge, 1.5 inch needle, 20 mg of triamcinolone acetate, and 1 mL of 1% lidocaine. Mark the point of maximal tenderness over the lateral epicondyle. Sterilize this area using three iodine swabs and an alcohol pad. Using sterile technique, aim the needle perpendicular into the point of maximal tenderness. Always aspirate before injecting. If blood is found in the aspirate, reposition. There should be no aspirate in this injection. If resistance is felt, do not inject. Resistance could indicate that the needle is in the tendon. Never inject directly into the tendon. Reposition and aspirate again. When there is no aspirate and the injectate flows smoothly, inject. Clean the iodine off with alcohol pads. Note that some physicians favor using 40 mg of triamcinolone acetate. In the authors’ experience, 20 mg is sufficient.

Modifying equipment may be all that is necessary to remove the offending agent. Changing racket size or string tension and using an electric screwdriver are two examples. An epicondylar strap worn beneath the elbow may be helpful when lifting heavy loads is unavoidable.

Physical therapy that focuses on gentle stretching and strengthening should also be used. In the acute phase, modalities such as ultrasound and soft tissue mobilization can be employed.

Most patients (>95%) heal completely with aggressive conservative care. In the rare refractory case, surgical debridement of the tendinosis with decortication of the lateral epicondyle is an option.

RADIAL TUNNEL SYNDROME

Background

Radial tunnel syndrome is sometimes called “resistant tennis elbow” because the symptoms may be so similar

to tennis elbow that the two are often confused. The diagnosis should be considered based on history and physical examination and also in patients diagnosed with lateral epicondylitis who have failed to respond to aggressive conservative therapy. Some physicians believe the two conditions may coexist in up to 5% of patients. In this syndrome, the radial nerve is compressed at the arcade of Frohse (which is at the elbow in the superior portion of the supinator) or in the inferior portion of the supinator muscle. Trauma can cause the syndrome, as can repetitive, forceful pronation and supination. At the site of compression, the radial nerve has branched into the posterior interosseus nerve, which is a purely motor nerve.

to tennis elbow that the two are often confused. The diagnosis should be considered based on history and physical examination and also in patients diagnosed with lateral epicondylitis who have failed to respond to aggressive conservative therapy. Some physicians believe the two conditions may coexist in up to 5% of patients. In this syndrome, the radial nerve is compressed at the arcade of Frohse (which is at the elbow in the superior portion of the supinator) or in the inferior portion of the supinator muscle. Trauma can cause the syndrome, as can repetitive, forceful pronation and supination. At the site of compression, the radial nerve has branched into the posterior interosseus nerve, which is a purely motor nerve.

Clinical Presentation

Patients typically present with pain over the lateral epicondyle. As with lateral epicondylitis, the patient’s pain is worsened with wrist extension and repetitive gripping and squeezing. Helpful distinguishing features of radial tunnel syndrome as opposed to lateral epicondylitis include night pain and pain that sometimes radiates over the forearm. In addition, the locus of pain is slightly distal to that of lateral epicondylitis. Occasionally, the pain refers to the dorsum of the hand. There are no sensory deficits (e.g., numbness) because only the posterior interosseous nerve is affected, which is a purely motor nerve. Patients do not complain of weakness in most cases. Weakness, if present, would include first digit and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) extension. Patients are able to extend their wrist but may have radial deviation.

Physical Examination

The middle finger test in which the middle finger is extended against resistance is likely to be positive in radial tunnel syndrome and in patients with lateral epicondylitis. One way to distinguish radial tunnel syndrome from lateral epicondylitis is to perform a Tinel test by tapping approximately 3 inches distal to the lateral epicondyle over

the course of the radial nerve. Reproduction of pain signifies possible radial tunnel syndrome. Strength testing is generally normal. If weakness is present, severe compression should be suspected and weakness may be detected with extension of the first digit and MCPs (interphalangeal joint extension is intact). Radial deviation on extension may be present.

the course of the radial nerve. Reproduction of pain signifies possible radial tunnel syndrome. Strength testing is generally normal. If weakness is present, severe compression should be suspected and weakness may be detected with extension of the first digit and MCPs (interphalangeal joint extension is intact). Radial deviation on extension may be present.

Diagnostic Studies

Electromyelography/nerve conduction velocity (EMG/NCV) studies may be performed to evaluate for radial tunnel syndrome, but this test has a high false-negative rate for this condition.

Treatment

Treatment consists of ice, relative rest (avoiding the offending activity if possible), and physical therapy. Wearing a lightweight plastic splint at night to reduce mobility of the elbow may help reduce unwanted supination and pronation while the muscles are relaxed during sleep. This may give the nerve an opportunity to heal. An injection of anesthetic and cortisone over the site of entrapment may be diagnostic and therapeutic. In severe cases, or recalcitrant cases, operative decompression may be necessary.

MEDIAL EPICONDYLITIS (GOLFER’S ELBOW)

Background

As with lateral epicondylitis, medial epicondylitis is a misnomer. The pathologic process is more tendinosis than tendonitis. Nevertheless, there is an inflammatory component. Medial epicondylitis is also called “golfer’s elbow,” but of course people other than golfers also are afflicted. The site of tendinosis is on the common tendinous origin of the flexor and pronator muscles slightly anterior and distal to the medial epicondyle.

Clinical Presentation

Patients are often 40 to 50 years of age and complain of medial epicondyle pain. The pain is exacerbated with activities that involve active forearm pronation and wrist flexion such as occurs when swinging a golf club, applying topspin in a tennis shot, using a screwdriver, and bowling. As the disease progresses, pain becomes more pronounced with less vigorous activities such as shaking hands.

If there is numbness or tingling extending into the medial forearm and fourth or fifth digits, ulnar nerve involvement should be suspected and interrogated for possible cubital tunnel syndrome.

Physical Examination

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree