Elbow and Forearm

History

Onset, mechanisms, previous injuries.

Symptoms including pain site(s), radiation, and temporal pattern, provocative factors/movements, swelling, locking, tingling, numbness, vascular changes, clicking.

Are there neck, forearm, or hand symptoms?

Examination

Inspection

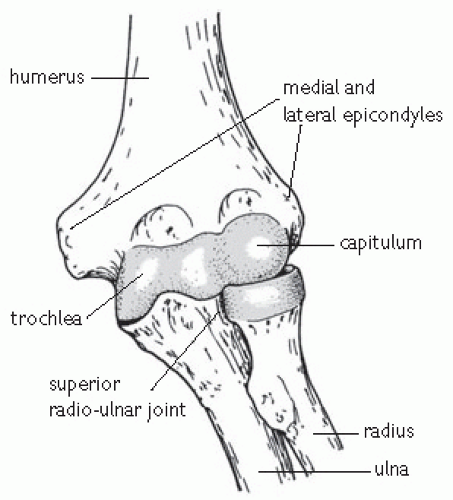

See Fig. 18.1 for the anatomy of the elbow joint.

Look at soft tissue contour for evidence of wasting or asymmetry of muscle bulk, muscle fasciculation, scars, deformities, and alignment. Over-development of the dominant arm is common.

Look for swelling and soft tissue masses in the antecubital fossa.

Estimate the carrying angle with the arm extended.

Inspect posteriorly for dislocation, olecranon bursa, effusion, and triceps tendon tear (excessively bony prominence, with a gap just above).

Inspect laterally for synovitis or effusion which may be evident in the triangular space between the lateral epicondyle, the head of the radius, and the tip of the olecranon.

Palpation

Examine the bony landmarks with the arm flexed at 90°.

Tenderness in the area of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) indicates injury.

Palpate the radial head for tenderness (fracture, synovitis, osteoarthritis, dislocation). Palpate the radiocapitellar joint during pronation/supination (degenerative change, synovitis).

Check the biceps tendon (tenderness) and brachial pulse in the cubital fossa.

Palpate the lateral collateral ligament and the lateral epicondyle.

Palpate the ulnar nerve posterior to the medial epicondyle for thickening and/or irritability. Anterior subluxation of the ulnar nerve is often evident with flexion and reduced with extension and can be associated with a click during movement.

The flexor-pronator muscle group may be tender (and even swollen) at its origin with medial epicondylitis.

Special tests

Lateral epicondylitis

Prime test: patient extends elbow, pronates the forearm and extends the fingers. The examiner applies downward force to the middle finger (extensor digitorum communis).

Resisted wrist extension is tested with the forearm pronated and the elbow in two positions: firstly extended then flexed to 90° (extensor carpi radialis brevis).

Medial epicondylitis

Resisted wrist flexion with the elbow flexed and forearm supinated.

Resisted forearm pronation with the forearm extended and in neutral rotation.

Distal biceps tendon

Remember to test by resisted supination with elbow in 90° flexion.

Neurovascular status

Tests of ulnar nerve entrapment: Tinel’s test, and sustained elbow flexion test (same principle to Phalen’s test at wrist).

Ulnar nerve instability: repeated flexion/extension of the elbow reproduces ulnar nerve symptoms and nerve subluxation.

Medial collateral ligament injury

History and examination

Acute or chronic medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury in adults is due to repetitive valgus extension overload which occurs usually in throwers, but can occur with direct trauma. MCL instability and a wedging effect of the olecranon into the olecranon fossa may cause a posterior osteophyte which can irritate the ulnar nerve. A sudden onset of pain during throwing, with an associated ‘pop’ or ‘snap’ may indicate an acute injury. In chronic cases there is progressive medial elbow pain that is functionally limiting and worse during the acceleration phase of throwing.

On examination there is swelling, local MCL tenderness and instability. Flexion contractures and cubitus valgus deformities are common in throwers. Posteromedial osteophytes may be palpable. Olecranon tenderness is worsened by bringing the arm into valgus and extension.

Investigations

Treatment

Aim to settle the acute symptoms where present and to restore normal range of motion with relative rest, ice, analgesics, and NSAIDs. PRP injection may be considered in lower grade injuries. Commence passive and active range of motion exercises early, with a strengthening regime. Throwing activities are resumed when there is full range of motion. Surgery is considered with chronic instability and impairment. Excision of osteophytes and local debridement or a straight osteotomy, 1cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon may be considered in those with impingement. For instability, reconstruction using a tendon graft; repair may be performed in the acute rupture.

Prevention of the condition is important through adequate conditioning, warm-up, stretching, and appropriate technique.

Medial collateral ligament instability in children

History and examination

This usually occurs in relation to throwing or racket sports. Medial apophysitis is a true epicondylitis due to traction and inflammation of the growth plate at the medial epicondyle. ‘Little Leaguer’s elbow’ is due to a variable combination of a medial apophysitis, MCL injury, and instability, compressive changes at the radiocapitellar joint and osteochondrosis. There is usually gradual onset of an aching pain at the medial elbow and there may be weakness of grip and paraesthesiae in the distribution of the ulnar nerve. An acute avulsion injury at the apophysis can also occur. In the acute avulsion there is a ‘pop’, followed by medial swelling and weakness.

On examination, there may be swelling and tenderness at the medial epicondyle, and perhaps bruising and flexion contracture. Pain is exacerbated by passive extension of the elbow and wrist. With an avulsion injury, a fragment may be palpable. Stress testing may show medial instability. Lateral elbow tenderness, pain on movement and on compression of the joint indicates lateral compressive changes.

Investigations

US demonstrates the state of the ligament, avulsion fragments, degree of separation, local fluid collection. MRI also may demonstrate bone bruising and state of growth plates. Plain X-rays may be normal or may show widening of the physis, fragmentation or avulsion of the apophysis, in comparison to the other side. Gravity valgus stress views may be considered.

Treatment

Relative rest, analgesics, ice, stretching. Healing can be prolonged. When avulsion has occurred, treat according to degree of displacement. Immobilize for 2 weeks with mild displacement followed by progressive rehabilitation. With large or rotated fragments, consider open reduction and fixation.

Traction apophysitis medial humeral epicondyle (‘Little Leaguers’ elbow’)

Causes

This condition is commonly seen in the young throwing athlete. The valgus force imparted to the elbow when throwing causes compression of lateral elbow structures and stretching of medial elbow structures. This results in traction of the wrist flexors on the medial epicondylar apophysis.

Clinical features

Insidious onset of pain over the medial epicondyle (common flexor origin), exacerbated by pitching, bowling, and throwing long distances.

May have difficulty fully extending the elbow.

Focal tenderness ± swelling over the common flexor origin.

Pain is reproduced by passive dorsiflexion of the wrist with the elbow in the extended position and with resisted wrist flexion.

Diagnosis

Usually clinical.

If onset of pain is acute, X-ray may be warranted to exclude an avulsion fracture of the medial epicondylar apophysis.

Treatment

Rest from throwing activities until pain resolves.

Stretching program for wrist flexors.

As pain improves, a strengthening program should be instituted to avoid further injury on resumption of throwing.

Return to sport should begin with throwing short distances at reduced pace and gradually increasing throwing distance and pace if asymptomatic.

Full recovery can be expected.

Lateral epicondylitis

History and examination

This is a tendinopathy of the common extensor—supinator tendon rather than epicondylitis. Degenerative micro-tears (due to repetitive mechanical overload) are found in the common extensor—supinator tendon, with the origin of extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) most commonly affected.

There is often a history of overuse, involving repetitive flexion-extension or pronation-supination activity. There is acute or chronic lateral epicondylar pain and tenderness worse with gripping. Among tennis players, the backhand stroke is commonly implicated and those players with a faulty technique are most likely to be injured. Equipment factors include a racquet that may be too heavy or too light, a grip that is too big, string tension that is too tight, and the use of heavy or wet tennis balls. 13% of elite players and up to 50% of non-elite tennis players have symptoms suggestive of lateral epicondylitis and approximately half of these have symptoms for an average duration of 2½ years. It may occur in other sports (e.g. golf—where it is more common than ‘golfers elbow’). It particularly affects those aged 40-60yrs.

On examination there is tenderness over the ECRB origin at the lateral epicondyle. The tenderness may be diffuse, over the origins of extensor digitorum communis (EDC) and/or extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL). One or more provocation tests may be positive. Look for other possible causes of lateral elbow pain including the neck. Examine the equipment and assess technique.

Investigations

US can be considered an extension of the clinical examination. It shows decreased echogenicity, inhomogeneity, and thickening of the tendon, and a local fluid collection may be seen. Micro-tears, typically on the deep surface, may be evident. Neovascularization, representing disordered repair, local calcification at the tendon insertion and irregularity of the bone surface may all be noted. Other imaging studies are not routinely performed unless other pathologies are suspected. A plain radiograph may help to evaluate for OA of the radiocapitellar joint. On MRI there may be increased signal intensity of the extensor tendons close to their insertion on the lateral epicondyle, and the surrounding anatomy can also be evaluated, either by plain MR or with the assistance of contrast. CT is best for bony anatomy (e.g. small osteophytes/loose bodies).

Treatment

Relative rest, ice (10min every hour in the acute stages), analgesia, and NSAIDs (topical NSAIDs are preferable). Compression straps or counterforce braces applied distal to the bulk of the extensor mass may help. The brace is tightened to a comfortable degree of tension with the forearm muscles relaxed, so that a maximum contraction is limited. Constant use of the brace not advised.

Stretching of the forearm extensors and range of motion exercises at the elbow and wrist should start early. Progressive rehabilitation for strength and endurance of the forearm extensor-supinator group as soon

as pain allows, progressing according to symptoms. Use ice after early rehabilitation sessions to limit an excessive inflammatory response. In chronic cases, NO patches, US-guided platelet rich plasma injection(s), and/or extracorporeal shock wave therapy may be considered. (NO (nitric oxide) releasing patches, also known as glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) patches, have been advocated in the treatment and repair of tendinopathies, primarily on the basis of enhancing tenocyte function. Low dose patches (e.g. ¼ Deponit 5 patch/24h) are used. Headaches and skin sensitivity may occur).

as pain allows, progressing according to symptoms. Use ice after early rehabilitation sessions to limit an excessive inflammatory response. In chronic cases, NO patches, US-guided platelet rich plasma injection(s), and/or extracorporeal shock wave therapy may be considered. (NO (nitric oxide) releasing patches, also known as glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) patches, have been advocated in the treatment and repair of tendinopathies, primarily on the basis of enhancing tenocyte function. Low dose patches (e.g. ¼ Deponit 5 patch/24h) are used. Headaches and skin sensitivity may occur).

Corticosteroid injections are no longer commonly recommended. There may be short-term pain relief, but there is no evidence of benefit over placebo in the longer term, and there are risks: SC atrophy, tendon rupture, and others.

Address the cause. In tennis players, technique and equipment factors must be addressed. Evaluation of technique with the help of a coach may prove beneficial. Improvements may be noted by avoidance of the leading elbow during backhand, ensuring that the forearm is only partially pronated, the forward shoulder is lowered, and the trunk is leaning forward. The patient should also consider a change in racquet (different weight, shock absorbency, grip size) reducing string tension to 2-3 pounds less than the manufacturers’ recommendations (i.e. 50-55 pounds), using slower, lighter tennis balls, and playing on slower courts.

Surgery is reserved for those patients with disabling symptoms who fail to respond to all the above measures over some months. Options include repair of the extensor origin after excision of the torn tendon, granulation tissue and local drilling of the subchondral bone of the lateral epicondyle, with an aim to increasing blood supply. The elbow is placed in a posterior plaster splint for a week, then in a lighter splint for 2 weeks, with the elbow in 90° flexion and in neutral rotation. Range of motion exercises are commenced thereafter, with a progressive strengthening regime. Light activities can be recommenced at 3 months, but the patient can expect to wear a counterforce brace initially.

Other surgical options include reduction of the tension on the common extensor origin by fasciotomy, direct release of the extensor origin or lengthening of the ECRB tendon distally. Fasciotomy and complete extensor tendon release can result in loss of strength, and lengthening of ECRB distally appears to be effective only in the minority of cases. Whilst intra-articular procedures such as synovectomy and division of the orbicular ligament have been suggested, these seem inappropriate for an extra-articular condition. Some surgeons advocate decompression of the radial or posterior interosseous nerves on the basis that posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) entrapment is contributing to—or is the primary cause of—chronic symptoms.

Medial epicondylitis

History and examination

This is not a true epicondylitis, but an overuse injury of the common tendinous origin of the flexor-pronator muscle group. It commonly occurs with repetitive flexion and pronation, less commonly with valgus stresses, and is seen in throwing and racket sports and in golfers (‘golfer’s elbow’). See Figs. 18.2 and 18.3.

It causes an acute/chronic aching pain at the medial elbow and proximal flexor musculature of the forearm. There may be weakness of grip. Some patients have paraesthesiae in the ring and little fingers suggestive of an ulnar neuropathy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree