Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the effectiveness of an analgesic protocol with nitrous oxide and anaesthetic cream (lidocaine and prilocaine, EMLA) for children undergoing botulinum toxin injections.

Patients and methods

Prospective study including 51 injection sessions, 34 children with a mean age of 5.94 (range 2–15) and 209 injected muscles. Pain was evaluated with the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS), the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the Face Pain Scale (FPS) for the children and with a VAS for the parents.

Results

CHEOPS score for the 51 sessions was 8.50 (S.D. 3.56). Forty-nine percent of scores were above the therapeutic threshold of 9; 25% of the children evaluated the pain above the therapeutic threshold of 3; 44.74% of the parents’ estimations exceeded 3. No correlation was found between age, weight, number of injected muscle and CHEOPS score.

Conclusion

The association of MEOPA and anaesthetic cream is only effective for 50% of children. This is much lower than treatments for other types of acute induced pain in children. Botulinum toxin injections and cerebral palsy children present certain specificities which require improvements in this analgesic protocol.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer le niveau d’analgésie induit par l’association du Mélange Equimolaire d’Oxygène et de Protoxyde d’Azote (MEOPA) et de la crème anesthésique EMLA (mélange de lidocaïne et de prilocaïne) lors des injections de toxine botulique chez l’enfant.

Patients et méthodes

Étude prospective monocentrique portant sur 51 séances d’injection, 34 enfants d’un âge moyen de 5,94 ans (min 2 ; max 15) et 209 muscles injectés. La douleur a été évaluée par les professionnels avec l’échelle de Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS), par les enfants avec l’échelle visuelle analogique (EVA) et l’échelle des visages révisée (FPS) et par les parents avec une EVA.

Résultats

Le score de CHEOPS sur l’ensemble des 51 séances était de 8,50 (ET 3,56). Quarante-neuf pour cent ont dépassé le seuil thérapeutique de 9. Le temps le plus douloureux était le temps de l’injection du produit. Le seuil thérapeutique de 3 à l’EVA et FPS des enfants a été franchi pour 25 % des séances. Le seuil thérapeutique de 3 à l’EVA des parents a été dépassé pour 44,74 % des séances. Aucune corrélation n’a pu être établie entre l’âge, le poids, le nombre de muscles injectés et le score de CHEOPS.

Conclusion

Le protocole MEOPA et EMLA est efficace dans un cas sur deux, ce qui est nettement inférieur aux autres gestes douloureux de pratique pédiatrique. Les injections de toxine botulique et les enfants paralysés cérébraux présentent des caractéristiques spécifiques qui incitent à améliorer la prise en charge de leur douleur.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Intramuscular botulinum toxin is a treatment for spastic hypertonia in adults and children with central nervous system lesions. For children with cerebral palsy, specific guidelines provide indications for injection and maximum dose per kilogram weight . An up-to-date literature review showed that botulinum toxin has grade A effectiveness for spasticity reduction in triceps surae and adductors in children . A recent study showed that botulinum toxin is an effective and safe long-term treatment . In France, authorization has only been granted in children for spastic equinus. A national study of physicians regularly using botulinum toxin showed that, in practice, indications for treatment are much broader with injections being carried out in all upper and lower limb muscle groups.

The increased use of botulinum toxin and the growing number of studies evaluating its effectiveness over the last 10 years contrasts with the paucity of established guidelines for the modalities of injection. Moreover, these types of injection have a three-dimensional specificity regarding pain in comparison with other painful acts carried out in children . Firstly, several intramuscular injections are carried out within the same session, this can be up to 12 injection sites . Secondly, the procedure for localization of muscles to be injected can be complex. Some muscles are deep such as tibialis posterior or psoas while other more superficial muscles may be located in sensitive areas such as the palm of the hand or the sole of the foot. Lastly, these injections are repeated regularly if they are found to be effective, usually until the end of the child’s growth in order to prevent secondary orthopaedic problems related to spasticity . These specificities, added to the fact that injections are now being carried out in younger children (18 months according to European recommendations) must be taken into account in order to evaluate and adapt the modalities of administration.

Internationally, most teams carry out these injections under short acting general anaesthetic . In France, practices are varied with a net tendency to use an analgesic protocol consisting of nitrous oxide and analgesic cream (mix of lidocaine and prilocaine called EMLA), combined or not with a sedative or other analgesic. Other teams only use general anaesthetic or use it as a second intention treatment.

The management of acute pain in children from 1 month to 15 years was the subject of guidelines by the National Agency of Health Accreditation and Evaluation (Anaes) in 2000 . The equimolar mix of oxygen and nitrous oxide is often used for the management of acute pain which occurs during treatments or painful procedures (lumbar punctures, intrathecal injections or myelograms). Collado et al. carried out a literature review which concluded that this substance is safe for a large number of disciplines . In 2002, the American Anaesthetic Society established that this substance could be used by medical and paramedical staff, who are not anaesthetists, with minimal risk . Indeed, this drug has many advantages since it not only has an analgesic effect but is also anxiolitic and sedating, while not affecting the laryngeal reflex (and therefore not requiring the presence of an anaesthetist) . It has unique physical properties: rapid action and short recovery time; as soon as inhalation is stopped.

EMLA cream (mix of lidocaine and prilocaine) is a surface anaesthetic. It is effective in less than 1 hour . The depth of anesthetized skin can be 3–6 ml depending on the penetration time. Its use alone is recommended for blood tests, insertion of a peripheral venous catheter, for vaccinations with multiple injections or for lumbar punctures .

The combination of nitrous oxide and EMLA is recommended by the Anaes for intense pain caused by penetration of the skin such as for a myelogram. To our knowledge, only Gambart et al. have attempted to evaluate pain during intramuscular botulinum toxin injections carried out under nitrous oxide and EMLA. Pain ratings were based on the global impression of the team. Pain intensity was scored using the following scale: 0 (none), + (moderate) or ++ (severe). A global score was obtained based on the average of this score. The authors reported that there was no pain in 45% of cases and injection-caused pain in 30% of cases. Their conclusion was that the pain prevention protocol was insufficient in one out of two cases.

The lack of consensus and the diverse practices of the different centers using botulinum toxin in France led us to further the study by Gambart et al. by evaluating the level of pain relief provided by the nitrous oxide–EMLA protocol using validated outcome measures. The principle aim of this study was therefore to determine the level of pain relief given by the nitrous oxide–EMLA protocol during multiple intramuscular injections of botulinum toxin and to use autoevaluation and heteroevaluation scales (medical team and parents) which have been validated for the evaluation of pain in children. The second aim was to determine if one aspect of the injection was more painful than others. The third aim was to determine if injecting particular muscles gave rise to more pain than others.

1.2

Patients and methods

1.2.1

Subjects

This was an open prospective monocentric study. The children were recruited from the specific consultation for botulinum toxin at Brest University Hospital. Recruitment began in September 2006 and finished in September 2008. The study was part of an evaluation of professional practice and as such did not require ethical approval. The inclusion criteria were: each child receiving botulinum toxin injections under the analgesic protocol of nitrous oxide and EMLA for whom the parents consented to the monitoring of pain during and after the injection. The exclusion criteria were: all premedication on top of the nitrous oxide and EMLA, lack of parental consent and the impossibility to precisely rate the pain during the session.

1.2.2

Session proceeding

The sessions took place in the pediatric day hospital in a department with experience in carrying out painful and invasive procedures (lumbar punctures, myelograms, blood tests). Each injection session was carried out by a team which consisted of a pediatric auxiliary, a nurse and an injecting physician.

The role of the pediatric auxiliary was to familiarise the child with the mask, to initiate the sedation by nitrous oxide, to hold the mask and to divert the child’s attention by a story, a song or any other method appropriate for each child. She monitored the child’s face in order to score the face items and the verbal complaints. The same paediatric auxiliary mostly participated in all 51 sessions.

The nurse (also mostly the same for all the sessions) diluted the Dysport 500 U botulinum toxin in 2.5 mg of saline solution using a 2.5 ml syringe. She helped to gain the child’s confidence, to prepare him, to remove the EMLA patches (mostly under nitrous oxide) and to disinfect after the procedure. During the injection, her role was to observe the child so that she could objectively score the pain and specifically the moment at which the pain occurred.

We arbitrarily divided the injection into three phases: the “puncture” phase when the needle penetrated the skin, the “localize” phase when electrostimulation was used to localize the correct needle position, and the “injection” phase when the substance was actually injected. At the end of each phase, the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale score (CHEOPS) was noted on the pain monitoring sheet. About 30 min after the procedure, the nurse evaluated the pain felt by the child with him and his parents.

The physician systematically placed the EMLA patches at least 1 hour before the procedure over the different areas which he planned to inject. Once the child was sedated and distracted by the pediatric auxiliary, the injections were carried out following a standardized protocol. All the injections were carried out using needles of the mark “TECA Myoject” which were 37 mm or 50 mm in diameter and a “Cefar Tempo” electrostimulator. The stimulation began at 2.5 mV. The localization of the muscles was done following the indications provided by Geiringer and Hang and Joel’s team .

Each phase was separated: puncture, localize, injection. The injection followed disinfection with dermic betadine and was quick and well within the area of anesthetized skin.

The localization phase corresponded to finding the part of the muscle for which a contraction could be induced with minimum stimulation. The injection time followed a slight aspiration, in order to avoid injecting in a blood vessel, and was progressive until the predetermined dose was injected. The maximal dose used was according to the European established level: 25 U Speywood per kilogram weight . The same physician carried out the 51 sessions.

All the paramedical day hospital staff was trained to use the pain evaluation scales. Over 3 months, the team trained to function in the manner described above in order to be as objective as possible when scoring pain.

1.2.3

Pain rating

Three scales were used for pain evaluation, each of which is recommended by the Anaes: CHEOPS score, a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) adapted for children or the Face Pain Scale (FPS) score of the child and the parent VAS.

The CHEOPS scale is recommended for the diagnosis and evaluation of the intensity of immediate postoperative pain as well as for the diagnosis and evaluation of the intensity of other types of acute pain when it begins in children from 1 to 6 years . It is used to evaluate the child’s behaviour during painful procedures by analysis of trunk and limb movements, facial expressions and screams or cries ( Table 1 ). We considered that this scale was the most adapted to the situation of botulinum toxin injection under nitrous oxide since the child cannot express himself clearly orally because of the mask and the effect of the nitrous oxide. We used it for all age groups considering that a child under nitrous oxide is a child with modified cognitive capacity. We did not consider the items “limb restraint” for the injected limb because of the necessary set up of the limb for the injections. The scale was used over the three phases of the procedure, for each muscle and for each child. The principal outcome measure used to determine the level of analgesia provided by nitrous oxide and EMLA in a complete session was the maximal CHEOPS score observed over the whole session, that is over the three phases of the procedure. This will be named “CHEOPS Max” in the rest of the article. The minimum possible CHEOPS score is 4 and the maximum is 13.

| Score | |

|---|---|

| Cry | |

| No cry | 1 |

| Moaning or crying | 2 |

| Scream | 3 |

| Face | |

| Smiling | 0 |

| Composed | 1 |

| Grimace | 2 |

| Child verbal | |

| Positive | 0 |

| None or other complaints | 1 |

| Pain complaints | 2 |

| Body (torso) | |

| Neutral | 1 |

| Shifting or/and tense or/and shivering or/and upright or/and restrained | 2 |

| Touch | |

| Not touching | 1 |

| Reach or/and touch or/and grab or/and restrained | 2 |

| Limbs | |

| Neutral | 1 |

| Squirm/kicking or/and drawn or/and up/tensed standing or/and restrained | 2 |

| Total score | |

| Min | 4 |

| Max | 13 |

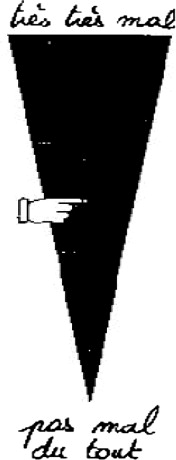

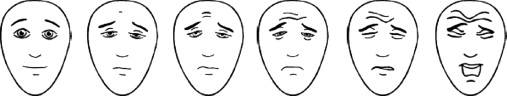

The VAS is recommended for children older than 6 years. It is considered as the gold standard for autoevaluation in this age group ( Fig. 1 ). We used the appropriate type of scale for the children (vertical, with triangle and adapted vocabulary). The instruction was the following: “place the hand as high as your pain was while you were wearing the mask”. Graduations at the back of the scale give a score from 0 to 10. If this evaluation was not possible or if the child was younger than 6 years, we used another scale recommended for this age group: the FPS ( Fig. 2 ) . The instruction given was: “these faces show how much something can hurt. This face shows no pain. These faces show more and more pain up to this one – it shows very much pain. Point to the one which shows how much you hurt while you were wearing the mask”. The score is between 0 and 10 depending on the face chosen. A heteroevaluation of the pain by the parents using a VAS is recommended when evaluation by the child is not possible or if the child is younger than 4 . This VAS is based on the same principal as the child VAS. The instruction given to the parents was: “put the hand as high as the pain felt by your child was while he was under nitrous oxide”.

1.2.4

Statistics

Statistica V6 was used for the statistical analysis. Because the principal variable “CHEOPS Max” was not normally distributed, we used non-parametric tests. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the distributions between the different phases of the procedure and between muscles injected. Correlation coefficients were calculated for the CHEOPS Max score and the clinical data or by group comparisons using the Mann-Whitney U test.

1.3

Results

Sixty-five sessions were carried out over the 2 years. Nine children were already premedicated on arrival or refused the nitrous oxide–EMLA protocol (usually because of a reluctance to wear the mask). Five children were difficult to evaluate during the procedure. A total of 51 sessions were included which represented injections of 209 muscles. The group included 34 children of which 16 were girls and 18 were boys with an average age of 5.94 years (S.D. 4.21, range 2–15) and average weight of 20.26 kg (S.D. 10.02, range 9–53.9). Thirty-three children had cerebral palsy (10 hemiplegic, 12 diplegic, 11 tetraplegic) and one child had adductor hypertonus relating to an orthopaedic problem. Four children had major cognitive problems associated with motor impairment. Twenty children had one session, 12 children had two sessions, one child three sessions and one four sessions in our consultation.

For 21 children, this was their first injection, for six, the second, for two the third and for five the fourth. Table 2 presents the muscles injected. An average of four sites was injected during the session with a maximum of eight sites. Average nitrous oxide flow was 9.17 l/min (S.D. 3.5, range 6–12) and the average length of the sessions was 11.79 min (S.D. 3.99, range 4–22). Three children vomited after the session with no other complication, two children had particularly vivid dreams.

| Muscles | Number of injections |

|---|---|

| Gastrocnemius | 62 |

| Soleus | 32 |

| Adductors | 44 |

| Medial hamstrings | 48 |

| Rectus femoris | 6 |

| Tibialis posterior | 3 |

| Pectoralis major | 2 |

| Lateral hamstrings | 2 |

| Peroneus longus | 3 |

| Brachialis | 4 |

| Biceps brachii | 1 |

| Tibialis anterior | 1 |

| Triceps brachialis | 1 |

| Total | 209 |

1.3.1

Pain score with the CHEOPS scale

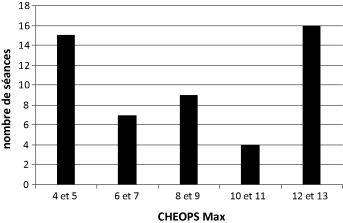

The average CHEOPS Max score over the 51 sessions was 8.50 (S.D. 3.56, range 4–13). The most frequent scores were the very low scores (4–5) and the very high scores (12–13) ( Fig. 3 ). The score was higher than the threshold of 9 in 25 sessions out of the 51.

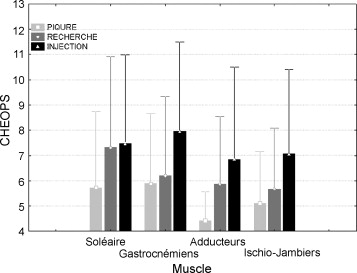

The average CHEOPS score observed during the puncture phase was 5.3 (S.D. 2.44, range 4–13), during the localisation was 6.24 (S.D. 3.07, range 4–13) and during the injection was 7.40 (S.D. 3.56, range 4–13). The differences between scores for the phases were significant. These significant differences were found across the 4 most injected muscles ( gastrocnemius , soleus , medial hamstrings, adductors) ( Fig. 4 ). There were no significant differences between CHEOPS Max scores for each of these four muscle groups.

1.3.2

Pain rating by the child and parents

The combined FPS score (used in two sessions) and VAS of the children (used in 22 sessions) of the 24 sessions in which the children were able to give an autoevaluation gave an average pain score of 2.41 (S.D. 2.51, range 0–10). In six sessions, the score was greater than the threshold of 3 which represents 25% of the sessions. The average parent VAS score for the 38 sessions in which the parents were present was 3.59 (S.D. 2.58, range 0–10). For 17 sessions, the threshold of 3 was surpassed; this represents 44.74% of the sessions.

For 11 sessions, we were unable to record this score because the parents were not present or due to the young age of the children.

1.3.3

Correlations between clinical factors and CHEOPS Max score

No significant correlations were found between age, weight and CHEOPS Max score. Children under the age of 5 had a slightly higher score (9.04, S.D. 3.23) than children over 5 years (8.03, S.D. 3.83) but this difference was not significant. The average score of the four children with cognitive impairments was 12.5 (S.D. 2.1) but this subgroup was too small to carry out statistical comparisons. Children with hemiplegia, diplegia or tetraplegia had similar CHEOPS Max scores (respectively 9.06, 8.52 and 9.10). Equally, the CHEOPS Max score was not different for children receiving injections in less than four or more than four muscles.

1.4

Discussion

The sample of children included in this study was mainly composed of children with cerebral palsy, a third of whom were hemiplegic, one third diplegic and the last third tetraplegic. This distribution is similar to the European population of cerebral palsy children . Our study shows that the average pain rated with the CHEOPS scale was 8.50. In 49% of children, this score was above the threshold of 9 which is described as the level of pain requiring treatment by the Anaes. However, over the 24 sessions which could be rated by the children, 75% were below 3 which is the critical level of the VAS for treatment . Parents were present during the procedure for 38 sessions and estimated 44.74% of sessions to be below the threshold for treatment. This type of divergence in results for analgesia with nitrous oxide has already been reported . One of the possible explanations is that the behavioural scale does not differentiate between anxiety and pain while parents and children can differentiate between these phenomena in their ratings. The nitrous oxide procedure requires use of a facemask and stress in very young children has already been reported for this treatment . The divergence in results also underlines the difficulties involved in rating pain in children and the complementarities of the results obtained. The CHEOPS scale is validated and particularly recommended for postoperative pain monitoring. The distribution of our results around the extremities of the possible scores (4–5 and 12–13) raises questions with regard to the sensitivity of this scale which may be too high. However, Gambart et al. assessed pain levels rated by the care team during botulinum toxin injections and found that pain relief was insufficient in half the cases. This is similar to our results.

Generally, the other studies which have evaluated nitrous oxide for analgesia during invasive procedures in children seem to report higher level of analgesia than our study. A study carried out in 31 French centres using this treatment evaluated 1019 inhalations in children with a median age of 6.4 years . Pain was scored with a VAS for children above 6 years of age and by a nurse or the parents for younger children. The scores on a 100 point VAS were as follows: 5 for 286 lumbar punctures 12.5 for 231 myelograms, 12 for 215 stitches, 18 for 75 superficial surgical interventions, 20 for 43 dental procedures. These VAS scores are all in the low pain range while in our study, children evaluated their pain as 2.41 out of 10 and the parents at 3.59 out of 10. These results show that botulinum toxin injections are quite particular with regard to the pain produced, in comparison with these other invasive procedures. Our results, which are less good, may be related to the population receiving the botulinum toxin injections. Indeed, a recent study showed that early painful trauma (such as a time in intensive care or neonatal unit) can alter the neurological processes related to the development of painful messages . A literature review showed that a certain amount of evidence exists showing that the unstable and immature physiological system of premature children made them potentially more vulnerable to repeated invasive procedures .

Our study also demonstrates a difference in reaction of the child during the three phases of the procedure. The puncture phase is much less painful than the other phases. This is probably related to the effect of the EMLA cream despite the fact that it only penetrates superficially (3 mm in 1 hour). We feel it is important to define the role of EMLA because the organizational constraints around its application and the waiting time are high. This cream has been shown to be effective over a variety of procedures and particularly for vaccinations and it also seems to be effective for botulinum toxin injections. The localization of the motor point is more painful than the puncture phase but the pain level does not increase substantially even if the difference is statistically significant. Because an electrostimulator was used for each procedure, we cannot differentiate between pain provoked by the electrostimulation or by the invasion of the muscle tissue. The highest level of pain was during the injection phase. This has not been previously reported for botulinum toxin but has been found for other substances injected intramuscularly.

The explanation most often given is the “irritability” of the product such as for acid vaccinations . Another possible explanation is that the dilution of the product results in a volume, which is too great for injection into small and/or retracted muscles.

The pain provoked in the four most frequently injected muscle groups was identical. A deep muscle such as soleus does not appear to provoke more pain than the more superficial gastrocnemius. We were unable to carry out statistical analysis on pain provoked by injection of the psoas muscle neither could we compare muscles in the upper and lower limbs because of the subgroups were too small.

We did not find any correlation between clinical factors (age, weight, clinical profile) and CHEOPS Max score. Nitrous oxide is however described as one of the most effective analgesics for painful procedures in children above 5 years of age . However, a recent study of vaccination by “Synagis” has also showed that nitrous oxide is effective in children less than 2 years of age. The number of injections in the same session does not appear to influence the CHEOPS Max score. Gambart et al. found that pain increased after eight injection sites. We did not inject more than eight sites and we cannot compare our data with regard to this. The former also included 10 polyhandicapped children out of 40 and these children appear to have higher pain levels than the other children. The four polyhandicapped children that we included also had a very high CHEOPS score (average = 12.5). Even if it is difficult to evaluate pain in these children, these preliminary data incite particular consideration with regard to analgesia for this population.

One factor which we did not evaluate was the satisfaction of the physician with regard to his procedure. Injections under general anaesthesia seem easier since the child is perfectly still during the injections. This consideration is important for the effectiveness of the treatment but also for the risk of penetration of blood vessels and diffusion of the toxin.

If we take into account the score of the CHEOPS scale which is the only scale which we were able to use on every subject, the analgesic protocol is effective in one out of two cases. The Anaes states that nitrous oxide is not a major analgesic and that it is not recommended to be used alone for severe pain. The alternative proposed by many centres in France and internationally is general anaesthetic. One centre in Europe reported that 94% of their botulinum toxin injections are carried out under general anaesthetic . Another alternative often practiced in France and in Europe is the addition of a hypnotic, anxiolytic or analgesic to the nitrous oxide–EMLA protocol. We did not find any data in the literature regarding the effectiveness of these protocols for botulinum toxin injections. The addition of hypnosis to the nitrous oxide would probably improve the protocol . Many analgesics are described in the literature for children but studies need to be carried out in order to evaluate them. Since we were unable to find a predictive factor for the effectiveness of nitrous oxide and EMLA, it is difficult to propose guidelines for their use. If general anaesthetic can be avoided for one out of two children by use of this protocol, it would seem to be the priority treatment for all children along with an objective pain evaluation. Depending on the pain rating, the addition of another medication could be proposed for the next session or a general anaesthetic in the case of severe pain. We feel that general anaesthetics should be a last resort, used for very deep muscle such as psoas, for very precise procedures such as for the upper limbs in very young children or for polyhandicapped children.

1.5

Conclusion

Nitrous oxide and EMLA is a protocol which is easy to put in place for pain management of invasive procedures in children. One out of two children undergoing botulinum toxin injection does not receive adequate pain control with this protocol but we did not find any predictive factors relating to its effectiveness. New analgesic protocols must be evaluated in order to improve practice.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La toxine botulique intramusculaire est un traitement de l’hypertonie spastique des adultes et des enfants présentant une lésion du système nerveux central. Pour l’enfant paralysé cérébral, son administration est encadrée par des recommandations européennes qui préconisent son injection dans le respect des indications et de dose maximale par kilo de poids . Une revue récente de la littérature montre chez l’enfant une efficacité de la toxine botulique avec un niveau d’évidence de grade A sur la spasticité du triceps et des adducteurs . Une étude récente montre que la toxine est un traitement efficace et sûr au long terme . En France, l’Autorisation de mise sur le marché (AMM) n’existe que pour le pied équin spastique de l’enfant. Un observatoire mis en place au niveau national montre que les indications retenues par les injecteurs sont en réalité beaucoup plus larges et en pratique, l’ensemble des muscles des membres inférieurs et supérieurs sont injectés.

L’utilisation croissante de la toxine botulique et le nombre d’études concernant son efficacité sur les dix dernières années contrastent avec le peu de consensus établi sur les modalités d’injections de la toxine. Ces injections ont pourtant une triple spécificité sur le plan de la douleur non retrouvée dans les autres actes douloureux liés à une maladie de l’enfant . En premier lieu, plusieurs injections intramusculaires se font lors de la même séance pouvant atteindre plus de 12 sites d’injections . La deuxième spécificité tient à la localisation des injections. Certains de ces muscles peuvent être profond comme le tibialis posterior ou le psoas et d’autres plus superficiel mais correspondant à des zones très sensibles comme la paume de la main ou la plante du pied. Enfin, ces injections sont à répéter dans le temps si elles font preuve de leur efficacité et le plus souvent jusqu’à la fin de la croissance pour prévenir les troubles orthopédiques secondaires à la spasticité . Ces spécificités ajoutées au fait que les injections se réalisent de plus en plus jeune (18 mois selon les recommandations européennes) nécessitent d’être prises en compte pour évaluer et adapter les modalités d’administration.

Au niveau international, la plupart des équipes pratiquent ces injections sous anesthésie générale courte . En France, les pratiques sont mixtes avec une nette tendance à l’utilisation d’un protocole antalgique par MEOPA et crème anesthésique (mélange de lidocaïne et de prilocaïne, EMLA), associé ou non à un sédatif ou un antalgique. D’autres équipes ne pratiquent que sous anesthésie générale ou bien l’utilisent en seconde intention.

La prise en charge de la douleur aiguë de l’enfant d’un mois à 15 ans a fait l’objet d’une recommandation par l’Agence nationale d’accréditation et d’évaluation en santé (Anaes) en 2000 . Le mélange équimolaire d’oxygène et de protoxyde d’azote (MEOPA) est couramment employé pour la prise en charge de la douleur aiguë provoquée lors de soins ou de procédures douloureuses (ponctions lombaires, injections intrathécales ou myélogrammes). Collado et al. ont conduit une revue de la littérature qui conclue à la sécurité de ce produit pour un nombre très large de disciplines . En 2002, la Société américaine d’anesthésie établissait que ce produit pouvait être utilisé par du personnel médical et paramédical « non anesthésiste » avec un risque minimal . En effet, il s’agit d’un médicament présentant de nombreux avantages puisqu’il a non seulement une action analgésique mais également anxiolytique et sédative, tout en préservant le réflexe laryngé (et ne nécessitant donc pas la présence d’un anesthésiste) . Il possède des propriétés physiques uniques : délai d’action rapide, période de récupération brève aussitôt l’inhalation stoppée.

La crème EMLA (mélange de lidocaïne et de prilocaïne) est un anesthésiant de surface. Son délai d’action est d’au moins une heure . La profondeur de peau anesthésiée peut être de 3 à 5 ml en fonction du temps de pénétration. Son utilisation est recommandée seule pour un prélèvement sanguin, pour une pose de cathéter veineux périphérique, pour les vaccins à injections répétées ou pour les ponctions lombaires .

L’association MEOPA et EMLA est recommandée par l’Anaes pour des douleurs intenses liés à un franchissement de la peau comme par exemple la réalisation d’un myélogramme. À notre connaissance, seule Gambart et al. ont cherché à évaluer la douleur lors des injections intramusculaires de toxine botulique sous MEOPA et EMLA. L’évaluation de la douleur était basée sur une appréciation globale de l’ensemble de l’équipe. L’intensité des manifestations était cotée par l’échelle suivante : 0 (nulle), + (modérée) ou ++ (importante). Un score global était établi sur la moyenne de cette cotation. Les auteurs rapportent ainsi l’absence de douleur dans 45 % des cas et la présence de manifestations douloureuses liées à l’injection dans 30 % des cas. Leur conclusion était que dans un cas sur deux le protocole avait été insuffisant.

Devant le peu de consensus et la pratique diversifiée des différents centres injectant de la toxine botulique en France, il nous a semblé important de compléter les données de Gambart et al., en évaluant le niveau d’antalgie apporté par le protocole MEOPA et EMLA à l’aide d’outils validés. L’objectif principal de cette étude a donc été de déterminer le niveau d’antalgie procuré par le protocole EMLA et MEOPA lors d’injections intramusculaires multiples de toxine botulique en utilisant des échelles d’auto et d’hétéroévaluation (équipe soignante et parents) validées pour l’évaluation de la douleur de l’enfant. Le deuxième objectif de cette étude était de déterminer si un temps de l’injection paraissait plus douloureux que les autres. Le troisième objectif était de déterminer si certains muscles semblaient plus douloureux à injecter que d’autres.

2.2

Patients et méthodes

2.2.1

Population

Il s’agit d’une étude prospective monocentrique ouverte. Les enfants ont été inclus à partir de la consultation spécialisée pour injection de toxine botulique du CHU de Brest. Le recrutement a débuté en septembre 2006 pour finir en septembre 2008. L’étude rentrait dans le cadre d’une évaluation des pratiques professionnelles et ne nécessitait pas d’avis de comité d’éthique. Les critères d’inclusion ont été : tout enfant bénéficiant d’injections de toxine botulique et d’un protocole antalgique par EMLA et MEOPA, dont les parents ont consenti au monitoring de la douleur durant et après le geste. Les critères d’exclusion ont été : toute prémédication en plus du MEOPA et de l’EMLA, l’absence de consentement des parents et l’impossibilité de coter la douleur de façon précise durant la séance.

2.2.2

Déroulement d’une séance

Les séances se sont déroulées au sein d’un hôpital de jour pédiatrique dans un service habitué à réaliser des actes douloureux et invasifs (ponctions lombaires, myélogrammes, prélèvements sanguins…). Chaque séance d’injection était réalisée par une équipe constituée d’une auxiliaire de puériculture, d’une infirmière et d’un médecin injecteur.

Le rôle de l’auxiliaire de puériculture a été de familiariser l’enfant avec le masque, d’initier la sédation par MEOPA, de tenir le masque, de divertir l’enfant par une histoire, une chanson ou tout autre moyen personnalisé à l’enfant. Elle surveillait le visage de l’enfant pour la cotation des items du visage et des plaintes verbales. L’auxiliaire de puériculture a le plus souvent été la même durant les 51 séances.

L’infirmière (le plus souvent la même durant les séances) a dilué la toxine botulique Dysport 500 U dans 2,5 ml de sérum physiologique à l’aide d’une seringue de 2,5 ml. Elle a aidé à la mise en confiance, à l’installation de l’enfant, à l’ablation des patchs d’EMLA (la plupart du temps sous MEOPA) et à la désinfection avant et après le geste. Durant le geste, elle était en position d’observatrice de façon à rester objective quant à la cotation de la douleur et en particulier au moment de survenue de la douleur.

De façon arbitraire, nous avons divisé l’injection en trois temps : le temps « piqûre » qui correspond au passage transcutané, le temps « recherche » qui correspond au temps de la recherche de la bonne localisation de l’aiguille grâce à l’électrostimulation et le temps de l’« injection » proprement dit. Après chaque temps, le score de Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS) a été noté sur une feuille de monitoring de la douleur. Trente minutes environ après le geste, l’infirmière évaluait avec les parents et l’enfant la douleur ressentie par l’enfant.

Le médecin installait systématiquement les patchs d’EMLA une heure au moins avant le geste aux différents endroits où il allait pratiquer les injections. Une fois que l’enfant était sous sédation et diverti par l’auxiliaire de puériculture, il pratiquait les injections selon un même protocole. Toutes les injections ont été pratiquées avec des aiguilles de marque « TECA Myoject » 37 mm ou 50 mm et un électrostimulateur de type « Cefar Tempo ». Celui-ci était réglé à 2,5 mV au début du geste. Le repérage musculaire s’est fait comme indiqué par Geiringer et l’équipe de Hang et Joel . Les trois temps du geste ont été distingués : piqûre, recherche et injection. La piqûre a été faite, après désinfection par de la bétadine dermique, d’un geste rapide en pleine zone d’anesthésie cutanée. Le temps « recherche » correspondait à la recherche de la zone du muscle qui induit une contraction pour une intensité minimale. Le temps « injection » venait après une légère aspiration, permettant d’éviter l’injection dans un vaisseau sanguin et se faisait progressivement jusqu’à la dose prédéterminée. La dose totale maximale utilisée est la dose recommandée au niveau européen : 25 U Speywood par kilo de poids . Le médecin a été le même sur l’ensemble des 51 séances.

Tous les soignants paramédicaux de l’hôpital de jour ont été formés à l’utilisation des échelles d’évaluation de la douleur. Pendant trois mois, l’équipe s’est entraînée à fonctionner comme décrit ci-dessus de façon à être le plus objectif possible dans la cotation de la douleur.

2.2.3

Évaluation de la douleur

Elle a reposé sur trois échelles dont l’utilisation est recommandée par l’Anaes : le score de CHEOPS, l’échelle visuelle analogique (EVA) adaptée à l’enfant ou l’échelle des visages révisée (ou Face Pain Scale, FPS) de l’enfant et l’EVA des parents.

L’échelle de CHEOPS est recommandée pour le diagnostic et l’évaluation de l’intensité de la douleur postopératoire immédiate ainsi que pour le diagnostic et l’évaluation de l’intensité des autres douleurs aiguës à leur début chez l’enfant d’un à six ans . Elle étudie le comportement de l’enfant lors des actes douloureux en analysant les mouvements du tronc, des membres, l’expression du visage et la présence de cris ou pleurs ( Tableau 1 ). Nous avons considéré que cette échelle était la plus adaptée à la situation des injections de toxine sous MEOPA puisque l’enfant ne peut pas s’exprimer clairement par oral du fait du masque et de l’effet du produit. Nous l’avons utilisée pour tous les âges, étant donné que l’enfant sous MEOPA est un enfant qui a des capacités cognitives modifiées. Nous n’avons pas considéré les items « contention aux membres » au niveau du membre injecté du fait de l’installation nécessaire du membre pour la réalisation des injections. Elle a été mesurée lors des trois temps du geste, sur chaque muscle et pour chaque enfant. Le critère principal retenu pour déterminer le niveau d’analgésie procuré par le MEOPA et EMLA au cours d’une séance complète est le score de CHEOPS maximal observé sur l’ensemble de la séance, c’est-à-dire sur l’ensemble des trois temps de l’injection. Celui-ci sera désigné dans la suite de l’article par l’intitulé « CHEOPS Max ». Le score minimum possible est de 4 et le score maximum de 13.