Abstract

Objectives

Highlight the role of patient education about physical activity and exercise in the treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA).

Methods

Systematic literature review from the Cochrane Library, PubMed and Wiley Online Library databases. A total of 125 items were identified, including 11 recommendations from learned societies interested in OA and 45 randomized controlled trials addressing treatment education and activity/exercise for the treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis.

Results

In the end, 13 randomized controlled trials and 8 recommendations were reviewed (1b level of evidence). Based on the analysis, it was clear that education, exercise and weight loss are the pillars of non-pharmacological treatments. These treatments have proven to be effective but require changes in patient behaviour that are difficult to obtain. Exercise and weight loss improve function and reduce pain. Education potentiates compliance to exercise and weight loss programs, thereby improving their long-term benefits. Cost efficiency studies have found a reduction in medical visits and healthcare costs after 12 months because of self-management programs.

Conclusion

Among non-surgical treatment options for hip and knee osteoarthritis, the most recent guidelines focus on non-pharmacological treatment. Self-management for general physical activity and exercise has a critical role. Programs must be personalized and adjusted to the patient’s phenotype. This development should help every healthcare professional adapt the care they propose to each patient. Registration number for the systematic review: CRD42015032346.

1

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common chronic joint disease and it greatly contributes to functional disability and loss of autonomy in the elderly . Nearly 40% of persons above 65 years of age have some type of symptomatic OA . The prevalence of OA increases as a function of age. The highest prevalence is in the hip, hand and knee (in that order). But this clinical diagnosis, which is later confirmed with standard radiographs, is often made late.

Recent studies tend to show a higher prevalence of mortality in OA patients than in the general population . In fact, an increase in all causes of mortality has been found among patients suffering from arthritis, including knee and hip OA. The main causes of mortality are comorbidities such as diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, along with the inability to walk . However, a more recent study found no significant differences between these two populations .

OA has long been considered a degenerative disease that is inevitable with age and cannot be stopped until the joint is replaced by a prosthesis. Even today, there is no truly curative treatment but current practices have evolved thanks to non-pharmacological, multidisciplinary care. These treatments require a change in lifestyle, with a focus on combating our increasingly sedentary way of life and weight gain. Regular physical activity in arthritis patients is effective at reducing pain and improving the function .

In 2002, the National Health Interview Survey found that arthritic patients were less physically active than the general population; in fact, 37% of the arthritic population is inactive. This sedentariness is associated with age, education level, functional limitations, access to fitness centres and mixed anxiety-depressive disorders . It can also be related to gender and BMI .

Without regular physical activity, muscle strength decreases. But we know that to stabilize the knee and stop the OA from getting worse, strength in the quadriceps and peripheral muscles around an injured joint is vital . A person’s physical activity level can be determined using standardized questionnaires such as the IPAQ ( Appendix A ). This questionnaire measures the amount of physical activity over a 1-week period . It is validated in patients with knee and hip OA. Studies have shown that the amount of physical activity differs depending on the OA location. It is lower in patients with hip or knee OA because of physical limitations in the legs. Overall, arthritic patients have a lower level of physical activity than the general population .

Muscle mass peaks at about 30 years of age; it then decreases 3–8% per decade, with even faster loss after 60 years of age. The most recent international definitions of sarcopenia have added decreased function due to less force-generating ability to the classic reduction in muscle mass criterion . It affects at least 20% of the population above 70 years of age, and affects more than 50% of those above 75 years, with predominance in the lower limbs. In arthritic patients, sarcopenia contributes to greater dependency due to loss of autonomy .

According to Costill et al. , the effects of training on body composition are similar in both elderly and younger subjects. Age does not seem to impact the strength gains and muscle hypertrophy that result from training. These strength gains are associated with increased cross-sectional area of both slow and fast-twitch muscle fibres. But the percentage of slow-twitch muscle fibres does not change with strength training. Instead, there is a specific increase in the type IIa fast-twitch fibres and a decrease in the type IIb fast-twitch fibres. The effects of aerobic training in the elderly are mainly due to an increase in oxidative capacity. These gains are similar in healthy people, no matter their age, gender or starting physical condition. Because of these physiological adaptations, an exercise program that combines strength and endurance work in arthritic patients could increase their functional capacity and reduce their pain.

However, to be fully effective, this exercise program must be accompanied by measures that improve treatment adherence . Many recommendations, including those of the EULAR , confirm that a combination of treatments is more effective than a single treatment. This suggests that patient education will help them adhere to programs because they will have a better understanding of their condition and treatment methods. And by identifying barriers to treatment compliance, these educational approaches can be used to set treatment objectives and action plans with buy-in from patients and therapists.

2

Objective

The main objective of this systemic review was to demonstrate the role of patient education about physical activity and exercise in the treatment of hip and knee OA based on the latest practice recommendations and data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The secondary objective was to focus on the obstacles and drivers for adhesion to physical activity programs.

2

Objective

The main objective of this systemic review was to demonstrate the role of patient education about physical activity and exercise in the treatment of hip and knee OA based on the latest practice recommendations and data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The secondary objective was to focus on the obstacles and drivers for adhesion to physical activity programs.

3

Methods

The review of literature is registered with the “Centre for Reviews and Dissemination” PROSPERO. Registration number: CRD42015032346.

The eligibility criteria were the PICOS characteristics. Of interest were studies of non-pharmacological treatment of knee OA, more specifically educational and physical activity programs. We looked at RCTs and written recommendations published in English from 2000 to 2015. We selected these parameters to provide a historical perspective for relatively recent data and “1b level and grade of evidence” to ensure that our review was relevant and credible.

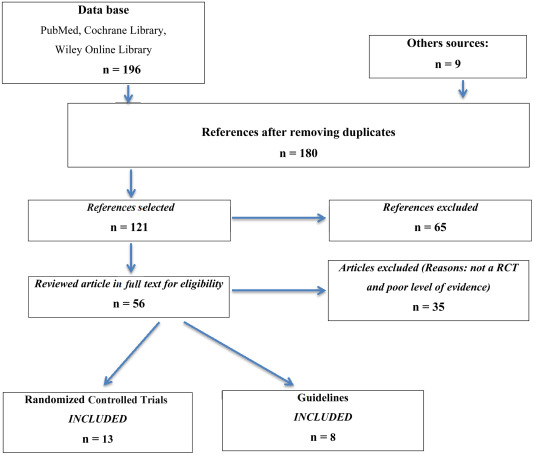

The Cochrane Library, PubMed, and Wiley Online Library databases were searched between February and December 2015. The last search was performed on December 31, 2015. Studies were selected from these databases using the following keywords: knee/hip and osteoarthritis/self-care/self-management/self-efficacy and physical activity/exercise . Our sample was supplemented by looking through the reference list of high-quality studies. The first sort was made by reading the title, abstract and then the articles. Only the following were retained: articles written in English, recommendations from learned societies dedicated to OA, and high-quality RCTs about treatment-based education for physical activity and exercise programs.

Our methods consisted of a systematic review of literature. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) analysis grid. The eligibility criteria for inclusion into the systematic review were based on PICOS. Inclusion was done with the endorsement of the investigator (EC). Data was extracted into a template established before starting the searches and then verified by double reading. Several variables for which data was collected were defined: patients suffering from knee OA who are the beneficiary of an educational and physical activity program with at least 3 months’ follow-up. These variables are consistent with the PICOS items. The funding sources were checked to make sure there were no conflicts of interest.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Method was used to evaluate the RCTs. For each study, we referred to the CONSORT grid typically used when performing RCTs. We then checked that the level and grade of evidence actually met our “1b” requirements. In addition, the patients had to be followed for at least 3 months. Articles with low-quality methodology (inadequate randomization, insufficient number of subjects, vague procedures) were excluded. Any recruitment bias was brought out. Volunteer-based recruitment can lead to inclusion of subjects that are more predisposed to changing. Having a large number of subjects in a study can reduce this bias. In addition, having some patient-reported outcomes (e.g., number of hours performing physical activity) can induce a bias in the results. This information is predominantly found in the Discussion section of articles.

4

Results

One hundred and twenty-one articles were read, including 45 RCTs and 11 recommendations. Only 13 RCTs and 8 recommendations were retained ( Fig. 1 ).

The recommendations made it possible to classify the various treatments based on their level of evidence. The triad of education, exercise and weight loss make up the first line of non-pharmacological treatments ( Table 1 ).

| Organization | Guidelines with high standard of proof and effect size | |

|---|---|---|

| OARSI 2014 | Exercise Weight loss Education | Pain and function Pain and function Pain |

| ESCEO 2014 | Information/education Weight loss if overweight, exercise (strength training, aerobic training) | Treatment adherence Function and pain Function and pain |

| NICE 2014 | Education Exercise Weight loss Biomechanical interventions | Pain, function, stiffness Pain, function, stiffness Pain, function, stiffness Pain, function, stiffness |

| AAOS 2013 | Education Exercise Weight loss Biomechanical interventions | Pain Function Disability Other symptoms |

| EULAR 2013 | Education Exercise Weight loss Lifestyle changes | Pain Pain and function Pain and function Pain and function |

| ACR 2012 | Exercise Weight loss | Pain and function Pain and function |

| RACGP NHMRC 2009 | Weight loss Exercise Education | Pain and disability Pain and function Treatment adherence Pain, quality of life |

| SOFMER SFR SOFCOT 2008 | Exercise Patient education, and psychological support | Pain and function Treatment adherence |

The selected RCTs allowed us to more specifically analyse the suggestions within the main recommendations and provided further detail about the practical implementation of these interventions ( Tables 2 and 3 ).

| Authors | Exercise: modalities | Education | Modalities | Tools used | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palmer et al. 2014 | Warm up: 5 minutes Circuit: 1 minute exercise–1 minute to move to the next station -> -> Strength/proprioception: progressive over 6 weeks | Setting of personal objectives Medical management of OA | Diet Home exercises Local community exercise opportunities | Booklet Home exercises Tool to aid goal setting | |

| Henriksen et al. 2014 | Warm up: 10 min, bike, intensity: moderate Training: strengthening/coordination/stability: core, hip, knee Difficulties: 6 level = A-F, repetitions: 2–3 × 6–8 exercises Method: strengthening | Importance of doing every exercise correctly and with proper technique | Exercises and progression in difficulty of these adjusted individually by physical therapist | The FITE-OA program Monitor knee pain intensity before, during, after training session (0 to 10) | |

| Tamara et al. 2012 | BWM: 12 first weeks: 90 min 3 ×/week Warm-up: 10 min > stretching + isometric strengthening: postural muscles 15 min (55% FCR) + 30 min (70% FCR) Aerobic: 60 min 1 week/2 12 following weeks: no supervision | PCST 12 first weeks: pain management 12 following weeks: interview PSCT BWM: weight loss 12 last: interview BWM | PCST: 60 minutes/week Attention diversion Cognitive-restructuring 60 minutes 1 week/2 Identification of difficulties 60 minutes/week Lifestyle, exercise, attitude, nutrition | BWM: group LEARN method Protocol on audio tape Manual PCST: group Role playing, bike Relaxation, imagery | |

| Brosseau et al. 2012 | Warm-up: 10 min light aerobic exercise Walking phase: 45 min -> aerobic 50–70% of HR max Cool down: 10 min -> light aerobic + stretching Progressively increase and maintenance: dosage, frequency, intensity | Discussing long-term goals Education Obstacles and drivers to adhere to the walking program | Long term Benefits of PA Moral support Self-management | PACE Ex Pedometer Log book Telephone support | |

| Hurley et al. 2007 and 2012 | Strength 35 to 45 minutes -> progressive = intensity/complex Aerobic -> individualized = capacity and disability Function/control Coordination | Diet Home exercises Drug management Pain management | Coping strategies Personal objectives and goal setting Action plan Diet and healthy eating | ESCAPE Knee Pain | |

| Coleman et al. 2012 (18) | Detailed information every session Instruction and demonstration Flexibility, aerobic and balance 2.5 h per week | Physiopathology Exercise Pain management/medication | Goal setting Small-group discussion Actively encouraged | Interactive Moderate didactic content Modelling | |

| Bezalel et al. 2010 | Active ROM exercises > strengthening > stretching | 45 min Daily life > straighten their leg out in front 5 s, 10 × each leg | Information OA Importance of performing exercise regularly Knee examination | Risk factors/information By physiotherapist | Detailed handout > instructions and photographs of the exercises |

| Ravaud et al., 2007 | Joint mobility: 10 × Muscle power -> if pain allows, increase of 5 repetitions/week Up to a maximum of 30 | Importance of motivation Exercise: 30 min with 5 repetition > demonstration by trainer | Usual care Home exercise Explanation: rheumatologist | Logbook => do completely Booklet > illustrating ex + videotape | |

| Yip et al. 2007 | Tai chi Walking Strengthening | Weekly | Disease management Compresses Joint protection | OA consequences: pain, fatigue, daily activity, limitations, stress Hot/cold + maintaining the same joint + heavy load | Pedometer |

| Veenhof et al. 2006 | Activity list (maximum 3) Evolution | Individually tailored exercises > impairments limiting the performance of these activities are selected | Education messages Treatment Positive reinforcement Goal | No pain relief Improvement functioning Select activity and define short and long term goals | Performance charts > record and view the performance of activity and exercise |

| Bennell et al. 2005 | 12 first weeks: isometric: gluteus, adductors Concentric: adductors/gluteus/quadratus lumborum Balance: 3 ×/day + tapping 12 following weeks: on their own | Knee taping Soft tissue massage of the knee Thoracic spine mobilization Home exercise program | Therapist for first four weeks and by participant thereafter Symptomatic leg extended and elevated on a chair After four weeks | Log book Standardized home exercises Taping instruction sheets | |

These studies have two potential biases: selection bias and data collection bias. Volunteer-based recruitment can result in the inclusion of subjects who are more prone to changing . Having a large number of subjects helps to reduce this bias . Subjects can be asked to report some information themselves, for example the number of hours of physical activity . This data can be either overestimated or underestimated by patients. Having a large number of subjects will also help to smooth out these data.

4.1

Current international recommendations for the treatment of hip and knee OA

Various practice guidelines have been published over the past 10 years (See Table 1 [2008–2014]). They were issued from various disciplines such as general practice (NICE , RACGP ), physical medicine and rehabilitation (SOFMER ), orthopaedics (AAOS ), rheumatology (ACR , EULAR ), or were multidisciplinary (OARSI , ESCEO ); various countries are represented.

4.1.1

History

Non-pharmacological treatments such as physical activity have been recommended by learned societies for the treatment of OA since 2000. Their role has evolved – non-pharmacological treatments now serve as the basis for treating this condition. The level of evidence is highest for the OA in the legs.

In 2008, NICE proposed that “treatment of OA starts with a non-pharmacological approach, which forms the basis of any proposed pharmacological treatment”. The ACR published recommendations in 2012 that were solely non-pharmacological . EULAR provided important details about non-pharmacological interventions in 2013. In 2014, the OARSI described four phenotypes of arthritic patients and adapted the non-pharmacological treatments based on these phenotypes. Also in 2014, ESCEO was the first organization to put forward a treatment algorithm to help practitioners navigate knee OA recommendations.

Given the lack of curative treatment other than joint replacement, it is essential that non-pharmacological treatments be pursued . Exercise and patient education are the first-line recommendations for all these organizations. Next are weight loss and interventions to alter biomechanics, with a similar level of evidence ( Appendix A ) ( Table 4 ).