Abstract

We present the complex case of a 49-year-old woman who worked as a cook in a school cafeteria and has been suffering from widespread pain since 2002. This patient showed a very particular gait pattern with hips adduction, flexed hips and knees and bilateral equinus foot deformity. Clinical examinations conducted by various clinicians, such as physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) physicians and neurologists, yielded very different diagnostic hypotheses, each being nevertheless quite “logical”: fibromyalgia syndrome with dystonia, CNS injury, Little’s disease, intramedullary spinal cord tumor or multiple sclerosis. The only abnormalities observed occurred during the quantitative sensory test presenting as severe widespread allodynia to cold and hot temperatures and during Laser Evoked Potentials shown as a dysfunctional pattern for central processing of nociceptive data. Gait analysis showed that parameters were in the norms. Considering these different tests and the excellent progression of the patient’s gait and general posture, we must envision that the fibromyalgia syndrome hypothesis remained the most likely one. The generalized dystonia was probably due to the patient’s analgesic protective attitude. The actual therapy is still based on the biopsychosocial approach.

Résumé

Nous présentons le cas complexe d’une femme de 49 ans ayant travaillé comme cuisinière dans une école et souffrant de douleurs diffuses depuis 2002. La patiente montre un schéma de marche très particulier avec une attitude en adduction de la hanche, flessum des genoux et des hanches ainsi qu’une malposition bilatérale des pieds en varus équin. L’examen clinique réalisé par des médecins de médecine physique et réadaptation (MPR) et des neurologues a conduit à des hypothèses diagnostiques très variées mais néanmoins cohérentes pour chacun de ces médecins : un syndrome fibromyalgique, une attitude dystonique, une lésion du système nerveux central (SNC), une maladie de Little, une tumeur médullaire ou une sclérose en plaques (SEP). Les seules anomalies observées lors de l’évaluation quantitative sensorielle par thermotest se traduisent par une allodynie sévère au chaud et au froid. L’étude des potentiels évoqués nociceptifs par stimulation laser met en évidence un schéma dysfonctionnel du traitement central des données nociceptives. L’analyse quantifiée de la marche fait ressortir des paramètres dans les normes admises. Au vu des résultats des différents tests, l’excellente évolution sur le plan clinique de la marche et de la posture générale de la patiente, nous pensons que l’hypothèse diagnostique du syndrome fibromyalgique demeure la plus probable. La dystonie est probablement due à un mécanisme de compensation antalgique. La prise en charge est à ce jour toujours basée sur l’approche bio-psycho-sociale.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a chronic pain disorder characterized by widespread pain, sleep disorders and fatigue. Although recognized by the World Health Organization and the American College of Rheumatology as an impairment disease, its etiology and pathogenesis are still not fully understood .

Several studies have already indicated that muscle strength and endurance are decreased in subjects with FMS, compared to control volunteers . But other studies report no difference in the force-producing capacity of leg muscles in women with FMS vs. controls.

To the best of our knowledge, no publications have featured FMS and a concomitant dystonic posture pattern. Therefore, authors would firstly like to highlight some clinical features and then move on to discussing this unusual association and propose a causal hypothesis regarding the biopsychosocial model.

1.2

Case report

In December 2006, our multidisciplinary team met a 45-year-old woman who worked as a cook in a school restaurant who had been suffering with chronic widespread pain since 2002.

Pain was exacerbated by physical efforts, remaining in a standing position for long periods of time, dampness and relieved by heat. The patient also reported intense fatigue associated with this pain. Daily, she had to delegate her domestic tasks to her husband and child. She depended on her husband for walking, doing the laundry and getting around (a wheelchair was needed for long distance trips). The patient also reported other associated symptoms such as restless legs syndrome (RLS), cognitive disorders such as difficulties for concentrating and focusing, headaches related to muscle tension in her neck, negative moods, but with some remaining hope. At that point, she was only followed by her psychiatrist.

Looking at her medical history we could see that the patient was premature baby born at 7 months of pregnancy, she walked at the age of 16 months and has a history of depressive mood. Furthermore, the patient is very hard on herself and very self-demanding.

1.2.1

Clinical evolution from 2007 to 2011

In February 2007, the patient showed a very particular gait pattern with small strides, hips adduction and flexion, fixed 30° knees flessum and a bilateral but reversible equinus foot deformity. Sensitive examination showed diffuse abnormal sensations, motor testing was normal but difficult to realize due to the patient’s stiffness in her lower limbs and pain in her right upper limb. Osteotendinous reflexes were sharp on four limbs and were negative for Hoffman and Babinski signs. The patient’s tender points were assessed (as defined by the ACR) at 18/18 and felt as “intense pressure” by the patient. We did not induce pressure-triggered allodynia of the soft tissues. The pain was self-evaluated, using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), at 80/100.

Our team proposed a multidisciplinary approach with the help of a nurse, physiotherapists, psychologists and physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) specialists. The nurse was the patient’s main contact. She collected data on the patient, regarding her history, beliefs, goals and means implemented to achieve these goals. She gave patients tools and advice to try and manage her pain by implementing distraction strategies: e.g. music, hobbies, and self-care. The physiotherapists collected information on the patient’s everyday physical activities and her beliefs on movements to evaluate her kinesiophobia. Teaching the patient to be aware of her body limits, her posture and emphasizing the importance of moving around: e.g. stretching, cardiovascular endurance at 65% of her capacity. The psychologists helped the patient manage her pain using a cognitive-behavioral approach, asking about her fears and pain-avoidance attitudes and behaviors. Then they taught her some coping and pacing mechanisms to deal with the pain. PM&R physicians were the team coordinators but also the patient’s primary contacts. They gathered her medical data such as treatment history and pain management habits. They conducted physical examinations, proceeded with diagnostic hypotheses and requested additional examinations when needed. They were in charge of the patient’s follow-up and treatment adjustments.

From 2008 to 2009, the patient’s dystonic pattern got worse in her lower limbs with more walking impairments also extending to her upper limbs, especially the right one with flexed elbow, wrist and fingers. Muscle stiffness was closely related to stress and personal annoyances but remained reversible. The patient also complained about weight gain and frequent cognitive impairments, which worsened her anxiety and lost hope in the future. After a short-term hospitalization suggested by our multidisciplinary team in order to give the patient some more advice and practical tools to better manage her daily life activities and pain, her functional evolution in her daily life activities was quite positive with improvement of her foot equinus deformity and knees flessum. The patient evaluated her pain on the VAS at 55/100. She started wondering about her own self-demanding personality and consequences on her symptoms.

During the year 2010, her gait pattern and posture improved up to 40–50%, according to the patient. A 5°-foot equinus deformity and a 10° reversible knees flessum were still present. The patient’s range of motion seemed less fluid: mobility of the shoulders and hips were limited due to muscle stiffness. Motor testing remained difficult to perform but appeared to be symmetric. We noticed a generalized pressure-provoked allodynia of the soft tissues. Tender points (ACR) were still rated as 18/18 and felt by the patient as “intense pressure”. Osteotendinous reflexes were normal on four limbs with an absence of Hoffman and Babinski signs. The patient at the time evaluated her pain at 40/100 on the VAS. She was about to have her own house built on land that she had found and thought everyday about new coping attitudes to improve her comfort and autonomy.

The actual therapy is still based on our multidisciplinary team follow-up associated to the biopsychosocial approach and medications: duloxetine, oxycodone, clonazepam (for her RLS), trazodone and zolpidem.

1.2.2

Additional examinations from 2007 to 2010

None of the several additional examinations unveiled any evidence of systemic, vascular or neurological disease: blood tests, electromyography, radionuclide whole body scan of the bones, radiographic imaging of the hips and knees, brain and spine MRI and sensitive and motor evoked potentials.

The quantitative sensory testing performed in 2007 revealed severe allodynia to cold and heat. Laser evoked potentials did not highlight any disorders in the central processing of nociceptive data. However, the quantitative sensory testing performed in may 2008 showed high cold and heat perception thresholds, amazingly the widespread allodynia to cold and heat had disappeared and instead the patient exhibited widespread cold and heat hypoesthesia syndrome. Still in 2008, the laser evoked potentials highlighted a normal pattern for somesthetic and thermonociceptive afferents but the dysfunction in the central processing of nociceptive data was still present.

A gait analysis was performed in 2007, using a commercialized treadmill Mercury LTmed, HPCosmos, Germany), with an appropriate conveyor belt (1500 mm length× 500 mm width) and sufficient power (2.2 kW). The driving system provided a range of constant speeds varying from 1 to 22km/h (by minimum increments of 0.1km/h). Segmental kinematics were measured with the Elite system (BTS, Italy) at 100 Hz. Six infrared cameras measured the coordinates, in the three dimensions of space, using 20 reflective markers positioned on specific anatomical landmarks. Working from Euler angles, we could compute the angular displacements of the pelvis, hip, knees and ankles in the three dimensions. Joint angles were evaluated using the classic method for clinical examinations. The neutral joint position was set at 0°. Negative values corresponded to extension in the sagittal plane, abduction in the frontal plane and external rotation in the transverse plane. Conversely, positive values corresponded to flexion in the sagittal plane, adduction in the frontal plane and internal rotation in the transverse plane. The velocity curve going forward for both captors placed on the metatarsal markers allowed for determining foot contacts, following the method described by Mickelborough et al. Step frequency and stance phase duration were derived from these foot contact periods. Ground reaction forces (GRF) were recorded by four strain gauges located under each treadmill’s corners. This force-measuring treadmill corresponded to a single platform, recording the global ground reaction force. The algorithm, described by Davis and Cavanagh, was used to evaluate the position of the center of pressure and vertical ground reaction force under each foot by separating the ground reaction force from the right and left gauges and again from the rear and front gauges. Horizontal ground reaction forces measured by the treadmill were also broken down. During single stance phases, horizontal forces measured by the four strain gauges were summed up and ended up being similar to those obtained when walking over ground. During the double stance phases, forces recorded on both gauges on the left side were separated from forces recorded on both gauges located on the right side of the treadmill in order to compute the force under the left and right foot.

We used inverse dynamics approach, GRF, kinematics and anthropometric data for computing the net joint moment for the hip, knee and ankle in the sagittal plane. The joint power of each joint was then transformed into the product of angular speed and net joint moment .

Muscle stiffness measurements for the ankle could not be performed because of the difficulties encountered when trying to install the patient into the measuring device. Surface EMG and electric muscle activity were recorded for the quadriceps femoris, biceps femoris, tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius lateralis using a telemetry EMG system (Telemg, BTS, Italy) with surface electrodes (Medi-Trace, Graphic Controls Corporation, NY, USA). The signal was digitized at 1000 Hz, full-wave rectified and filtered (bandwidth 25–300 Hz). The onset and cessation of muscle activity were both visually and mathematically determined by computing the EMG threshold voltage as described by Van Boxtel et al. .

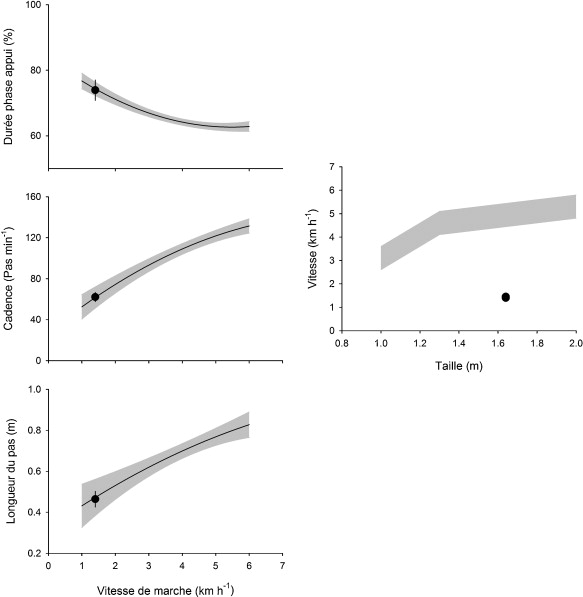

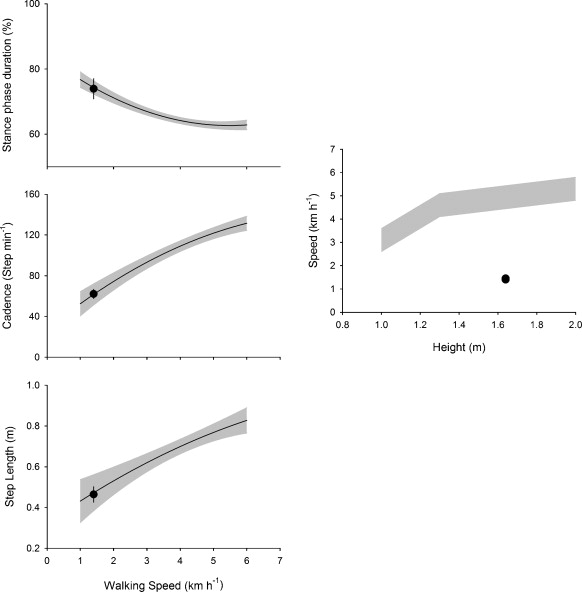

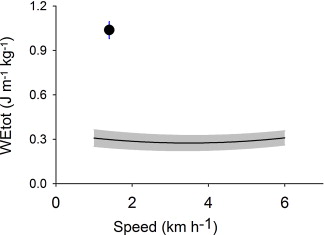

The patient walked on the treadmill at two speeds: 1.4 km/h and 2.5 km/h. Results were compared to values from a healthy population walking at the exact same two speeds. Gait analysis showed that parameters were within the norms ( Fig. 1 ), particularly the normal walking speed/distance ratio, contrary to values obtained in patients suffering from spastic diplegia. The patient’s spontaneous walking speed was set at 1.45 km/h, more than 3 times slower than the expected speed for a person her height.

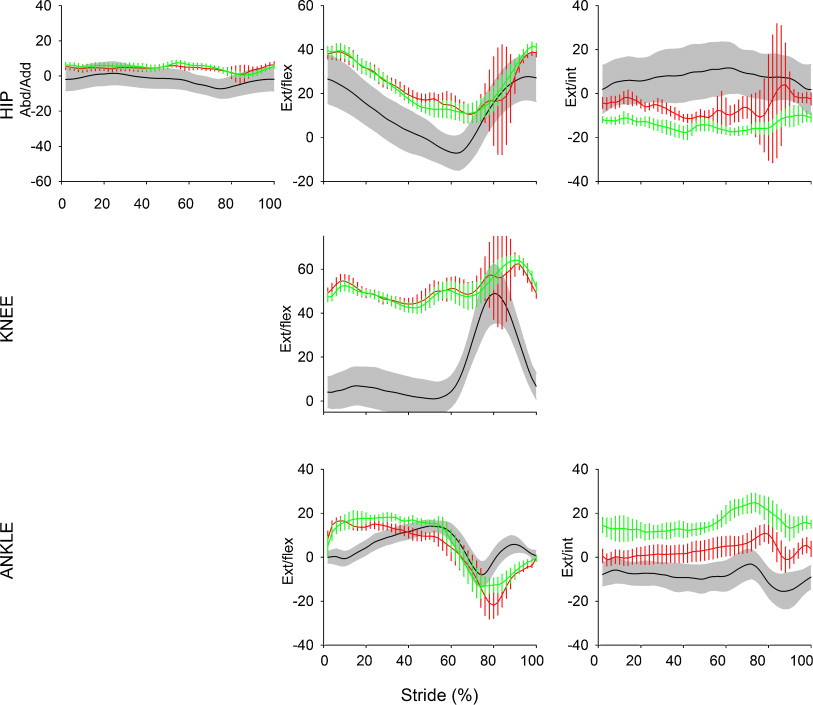

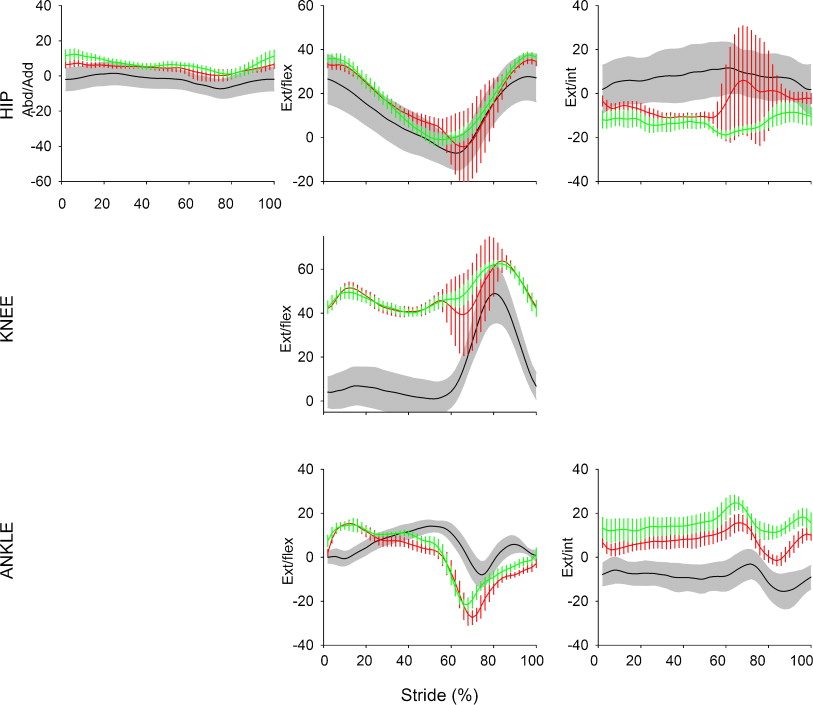

The kinematic analysis showed ( Fig. 2 ):

- •

that the patient had in fact a walking pattern with a false equinus foot deformity and digitigrade-type walk probably due to the bilateral knee flessum;

- •

a mild improvement of this knee flessum associated with an improved knee flexion during the swing phase at increased speed.

Mechanical analysis ( Fig. 3 ) showed:

- •

mild increase of internal mechanic work (internal energy output) when the patient walked at a slow speed, with an improvement and return to normal when the patient walked at a faster speed;

- •

high increase of external mechanic work (external energy output) when the patient walked at a slow speed (3 times higher than controls), mainly due to the energy expenditure used for lifting and shifting the body center of mass. An improvement was noted at a faster speed while remaining pathological (2 times higher than controls). Oxygen consumption was increased, which could indicate an inefficient and energy-wasting walking pattern.

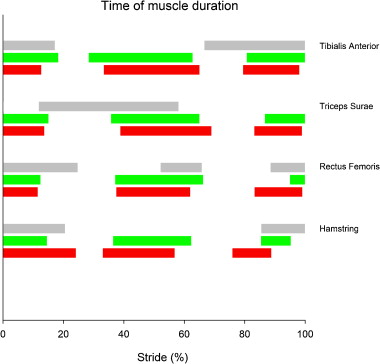

Surface EMG ( Fig. 4 ) showed a co-contraction pattern for the quadriceps femoris/biceps femoris and tibialis anterior/triceps surae agonist/antagonist couples, desynchronized contraction pattern vs. controls but data were difficult to analyze due to irregular muscle activations from one gait cycle to another.

1.3

Discussion

First, we did notice some recurrent clinical features such as: pain, stiffness in all limbs, foot equinus deformity and knees flessum. All these clinical features improved with the care and advice given by our multidisciplinary team and the patient’s outmost involvement in these intricate care improvement dynamics.

Concomitantly, the patient developed new ways to improve her everyday activities, task performance and social interactions.

Secondly, we would like to discuss this unusual association of dystonic pattern and FMS and progressively introduce a biopsychosocial causal hypothesis model.

1.3.1

Muscle tone

Commonly two terms are used to clinically identify muscle tension: muscle tone and muscle spasm. Unfortunately, both terms are ambiguous since they are used with different meanings. Muscle tension depends physiologically on two factors: basic viscoelastic properties of soft tissues associated with the muscle and/or degree of activation of the muscle’s contractile apparatus. EMG recordings can only identify electrogenic contractions and not endogenous contractures of the contractile apparatus of skeletal muscles, because the latter occur without any electrical activity in the muscle cell .

Muscle spasm is an uncontrolled electromyographic activity independent of posture. It may or may not be painful . Resting muscle tone is defined as the elastic and/or viscoelastic stiffness in the absence of contractile activity . Viscoelastic ankle stiffness in subjects with FMS may be quantified by assessing the passive sinusoidal movements of the ankle. We can observe an increase in elastic muscle stiffness as well as various types of viscous muscle stiffness in both ankles for that population. Some authors have reported that measuring resistance to the passive sinusoidal ankle movements could offer a valuable method for quantifying the subjective feeling of stiffness described by persons with fibromyalgia . The self-perceived increased ankle stiffness reported by younger and middle-aged FMS subjects might be due to changes in elastic and/or viscous musculoarticular structures around the ankle .

In the case of our patient this kind of evaluation could not be performed because of great difficulties encountered when trying to install her in the measuring device.

Hypertonia is generally used to describe increased muscle tone regardless of the reason. It covers a variety of conditions such as spasticity, rigidity, dystonia and muscular contracture . Dystonia is defined by the Disorder Movement Society (DMS) as a syndrome of abnormal, involuntary muscle movements due to sustained muscle contractions resulting in twisting and/or repetitive patterned movements. The neural mechanism underlying dystonia probably involves a common final pathway of reduced inhibition of thalamocortical output resulting in simultaneous contraction of agonist and antagonists muscles. Dystonia can affect either a single body part, contiguous body parts or can be generalized to the entire body . Emotional or physical stress, anxiety, lack of sleep, sustained medication use and cold temperatures can worsen symptoms .

Looking at this definition, our patient’s particular muscle tone pattern could be viewed as dystonia but we could not unearth any literature regarding a potential FMS-dystonia relationship.

1.3.2

Pain syndromes and posture

Janda and Schmid identified in a relevant and consistent manner a relationship between a number of muscular and postural changes and pain . In his study based on thorough and comprehensive examinations of the musculoskeletal system of approximately 2000 patients with FMS patients, Seibel found that not only did virtually all patients with FMS exhibit many of these muscular and postural changes, but he also identified several other changes and clinical symptoms related to the musculoskeletal system .

Muscle shortenings due to spasms results in muscle dysfunction. This fundamental feature may be due to spasms in the early phase of the injury and thus referred to as “the neuromuscular dysfunction phase”. It can also be due to contractures in the later stage of injury and referred to as “the dystrophic phase” .

1.3.3

Gait analysis

Findings by Pierrynowski et al. in 2005 have suggested that patients with FMS walk with similar stride length, time, velocity, joint angular kinematics and ground reaction forces than healthy volunteers. However, internally they use different muscle recruitment patterns. Specifically, subjects with FMS preferentially power their gait using their hip flexors instead of their ankle plantar flexors, a muscle recruitment pattern similar to fast-walking controls. Since fast walking is tiring, this recruitment pattern could suggest that persons with FMS walking at a comfortable speed are in fact, on a neurological level, walking at fast speed with the corresponding increased metabolic demand and fatigue .

In their preliminary study regarding gait patterns in persons with FMS, Auvinet et al. in 2006 reported that the walking speed was largely reduced for FMS patients in regards to healthy volunteers. Furthermore, the authors noticed a significant reduction of the stride length and frequency. Bradykinesia appeared to be one of the essential characteristics of the gait pattern in patients with FMS. It was in fact the most discriminating variable between controls and pathological subjects. Furthermore, this variable has been directly connected to the subject’s impulse in the craniocaudal axis .

Let’s note that our patient had a spontaneous walking speed of 1.45 km/h, i.e. three times lower than the expected speed for her height. Besides that, her stride length and frequency were normal. She had a highly increased external work when walking at a slow speed (3 times higher than controls), specifically due to the energy implemented for lifting and shifting her body center of mass. It improved when she walked at a faster speed while remaining pathological (twice higher than controls).

1.3.4

Fibromyalgia and stress

“Stress” can be defined as the collective physiological and emotional responses to any stimulus inducing fairly stereotypical changes in the function of the autonomic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis associated with exposure to stressors . “Distress” can be defined as psychological stress, typically implemented as a combination of depression and anxiety . Many studies have identified abnormalities in the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system in FMS and chronic pain. But although abnormalities are typically identified between mean values in pathological subjects and controls, there are never any dysfunctions of the stress processing system in patients and there is always a tremendous overlap between individuals within both groups (patients and controls). Even the nature of the abnormality is inconsistent, some subjects exhibiting hypoactivity and others hyperactivity of both the HPA axis and sympathetic nervous system .

The role of psychological distress in triggering FMS and related diseases is no longer accepted as a dogma. Data linking psychological distress to these pathologies is quite tenuous, and certainly more complex than initially imagined. It is now clear that the higher rates of distress seen in many case-control studies could in fact be due to some study biases since they were conducted in tertiary care settings, or among individuals with high healthcare-seeking behaviors. These biases could be reduced by performing studies in the general population. These studies have consistently shown that individuals with high baseline levels of psychological distress were only somewhat more likely to subsequently develop chronic regional or widespread pain . Many more individuals without baseline distress develop regional or widespread pain than those with baseline distress.

1.3.5

Fibromyalgia and negative moods

Mood disorders are common among patients with fibromyalgia, but the impact of psychological symptoms on central pain processing in this disorder remains quite unclear. The differential effect of depressive symptoms, anxiety and catastrophizing were investigated for pain symptoms and self-rating of one’s general health status as well as sensitivity to pain and cerebral processing of pressure-type pain.

Correlation analysis showed that depressive symptoms, anxiety and catastrophizing were correlated with subjective ratings of one’s general health status, but did not correlate with evaluating clinical pain or sensitivity to pressure pain. Imaging results showed that brain activity during experimental pain was not modulated by depressive symptoms, anxiety and catastrophizing. Negative moods in subjects with FMS can thus lead to a poor perception of one’s physical health but do not influence the performances of assessing clinical and experimental pain. There seems to be evidence to the notion that two partially divided mechanisms could be involved in the neural processing of experimental pain and negative affect .

1.3.6

Biopsychosocial approach

The patient’s care management was designed according to the biopsychosocial model, a conceptual model suggesting that psychological and social factors must also be included along with biological variables for understanding a person’s medical condition. It has replaced the outdated biomedical reductionist approach of medicine. In this new model, pain is rather viewed as an interactive, psycho-physiological behavior pattern that cannot be separated into distinct, independent psychosocial and physical components .

Recent meta-analyses concluded that a multidisciplinary treatment including cognitive-behavioral therapies had a significant effect on self-efficient pain management post-treatment and at follow-up. There was strong evidence that the positive effects on physical fitness could be maintained on the long term. Nevertheless, there was no evidence of efficacy on pain, fatigue, sleep disruptions, depressive symptoms, health-related quality of life, or self-efficient pain management on the long term. Operant behavioral treatment significantly reduced the number of physician visits at follow-up. .

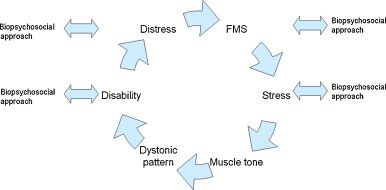

Those elements, muscle tone, dystonic pattern, distress, FMS disability and biopsychosocial approach could be put into synergy as showed on the interaction hypothesis model in Fig. 5 .

1.4

Conclusion

The clinical symptoms exhibited by our patient and analyzed by different specialists in PM&R, neurology and psychiatry can lead to different diagnostic hypotheses remaining nevertheless each one remaining quite “logical”: fibromyalgia syndrome with dystonic pattern, lesion of the CNS, Little’s disease, intramedullary spine tumor, multiple sclerosis or somatoform disorder. FMS was our first hypothesis based on clinical symptoms and patient’s history. Further clinical examinations could discard the other hypotheses as also observed with the excellent evolution of the patient’s gait, posture and pain symptoms during the 4-year follow-up along with the positive progression of the FMS clinical course as managed by the patient and our multidisciplinary team. We can only fathom that the generalized dystonia was initially triggered by the patient’s analgesic defense attitude that subsequently progressed to this pathological posture pattern.

Further studies evaluating the relationship and onset of dystonia persons with FMS should be considered.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank G. Stoquart (MD, PhD), C. Detrembleur (PT, PhD), V. Fraselle (MD), F. Dierick (PT) and all the team of the Multidisciplinary Center for Managing Chronic Pain (Centre de référence multidisciplinaire de la douleur chronique [CRMDC], cliniques universitaires UCL de Mont-Godinne) for their kind contribution to this work.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Le syndrome de fibromyalgie est une entité nosologique caractérisée par des douleurs musculaires chroniques diffuses (myalgies diffuses) et se manifestant aussi, notamment par une fatigue chronique et persistante et un manque de sommeil réparateur. Bien que reconnue par l’Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS) et le Collège américain de rhumatologie (American College of Rheumatology) comme une maladie invalidante, ses étiologies et pathogenèse sont encore mal comprises .

Plusieurs études montrent une diminution de la force et de l’endurance musculaire chez les patients fibromyalgiques, en comparaison avec une population témoin de volontaires sains . Mais d’autres études ne rapportent aucune différence dans la capacité de production de force musculaire des membres inférieurs chez des femmes atteintes de fibromyalgie versus une population témoin de volontaires .

À l’heure actuelle et à notre connaissance, il n’existe aucune publication sur la fibromyalgie associée à une attitude dystonique. Nous aimerions donc commencer par étudier certaines caractéristiques cliniques et ensuite discuter de cette association inhabituelle en proposant une hypothèse causale selon le modèle bio-psycho-social.

2.2

Étude de cas

En décembre 2006, notre équipe multidisciplinaire rencontrait une femme de 45 ans qui travaillait comme cuisinière dans une cantine scolaire et souffrait de douleurs diffuses chroniques depuis 2002.

Les douleurs s’intensifiaient pendant les efforts physiques, lors d’une station debout prolongée et avec l’humidité mais s’amélioraient avec la chaleur. Une fatigue intense était associée à ces douleurs. Tous les jours la patiente déléguait les travaux domestiques à son mari et son enfant. Elle était dépendante de son mari pour marcher, pour l’entretien du linge et ses déplacements (un fauteuil roulant était nécessaire sur les longues distances).

La patiente se plaignait également de symptômes associés : syndromes des jambes sans repos (SJSR), troubles cognitifs comme des difficultés de concentration, de céphalées causées par des tensions musculaires dans les cervicales et enfin des troubles de l’humeur, mais elle gardait espoir d’aller mieux. Elle n’était alors prise en charge que par son psychiatre.

Dans ses antécédents, nous notons une prématurité, la patiente est née à sept mois de grossesse, a acquis la marche à 16 mois, a des affects dépressifs et est très exigeante vis-à-vis d’elle-même.

2.2.1

Progression clinique de 2007 à 2011

En février 2007, la patiente présente une marche très particulière avec des petits pas et une attitude en adduction et flexion des hanches, un flessum des genoux à 30° et une malposition des pieds en varus équin bilatérale réductible. L’examen sensitif révèle des sensations diffusément anormales, le testing moteur est normal mais difficile à réaliser à cause de la raideur des membres inférieurs et de la douleur ressentie par la patiente dans son bras droit. Les réflexes ostéotendineux sont normaux pour les quatre membres et on note une absence de signe de Babinski ou de Hoffman. La patiente rapporte 18/18 des points douloureux (critères de l’American College of Rheumatology) évoquant une sensation de « forte pression ». Nous n’évoquons pas d’allodynie à la pression des tissus mous. La douleur est évaluée à 80/100 par la patiente à l’aide d’une Échelle Visuelle Analogique (EVA).

Notre équipe a alors proposé une approche multidisciplinaire, avec l’intervention d’une infirmière, de kinésithérapeutes, de psychologues et de médecins de médecine physique et réadaptation (MPR). L’infirmière étant le contact principal de la patiente, elle collecte les informations la concernant y compris ses antécédents familiaux et médicaux, ses croyances, ses objectifs et les moyens déjà mis ou à mettre en place pour les atteindre. L’infirmière va donner à la patiente des conseils pour gérer la douleur au quotidien en utilisant des techniques de distraction : musique, hobbies, prendre soin de soi… Les kinésithérapeutes s’occupent de collecter les données sur les activités physiques quotidiennes de la patiente et ses impressions sur ses mouvements. Ils évaluent aussi le degré de kinésiophobie de la patiente, et lui apprennent à prendre conscience des limites de son corps, de sa posture et soulignent l’importance de bouger avec des étirements et des exercices d’endurance cardiovasculaire à 65 % de sa capacité d’effort théorique. Les psychologues quant à eux proposent une gestion de la maladie par une approche cognitivo-comportementale. Ils collectent auprès de la patiente des éléments subjectifs comme les croyances, les peurs et les techniques d’évitement face à ses douleurs. Ils lui apprendront ensuite à mettre en place des solutions pour gérer et faire face à ces douleurs (stratégies de « coping » et de « pacing »). Les médecins MPR sont les coordinateurs de l’équipe mais également le premier point de contact avec la patiente. Ils s’attachent à recueillir les données médicales comme les antécédents médicaux, traitements en cours et gestion de la douleur. Ils procèdent à un examen médical complet, émettent des hypothèses diagnostiques et demandent, si nécessaire, des examens complémentaires. Ils sont responsables du suivi de la patiente et de l’évaluation des traitements.

Durant les années 2008 et 2009, son attitude dystonique s’est aggravée au niveau des membres inférieurs avec une augmentation des difficultés à la marche, s’étendant également aux membres supérieurs, tout spécialement dans le bras droit avec une attitude en flexion du coude, poignet et des doigts. La raideur est toujours liée au stress et à diverses contrariétés personnelles mais reste toujours réversible. À cette époque la patiente rapporte également une prise de poids et des troubles cognitifs fréquents, aggravant son anxiété et sa perte de confiance en l’avenir. Notre équipe multidisciplinaire lui propose alors une courte hospitalisation pour lui prodiguer des conseils sur la prise en charge de sa douleur et de ses activités au quotidien. Son évolution fonctionnelle est satisfaisante avec une amélioration de son varus équin et du flessum des genoux. La douleur, évaluée avec l’EVA, est de 55/100. La patiente prend également conscience de son extrême exigence envers elle-même et de l’impact de cette exigence sur ses symptômes.

La patiente rapporte une amélioration de sa marche et de sa posture générale d’environ 40-50 % au cours de l’année 2010. Un varus équin de 5° et un flessum de genou de 10° sont encore présents. Les amplitudes articulaires semblent moins fluides : la mobilité des hanches et des épaules est limitée par un phénomène de raideur musculaire. Le testing moteur reste difficile à réaliser mais apparaît symétrique. Nous remarquons une allodynie généralisée à la pression des tissus mous. Les points douloureux (ACR) sont toujours au nombre de 18/18, avec une sensation de « forte pression ». Les réflexes ostéotendineux sont normaux aux quatre membres, aucun signe de Hoffman ou de Babinski. La douleur est évaluée à 40/100 par la patiente à l’aide de l’EVA.

La patiente se prépare à faire construire sa maison sur un terrain qu’elle a trouvé et elle réfléchit chaque jour à de nouveaux moyens d’améliorer son confort de vie et son autonomie. Son traitement actuel est toujours basé sur le suivi de l’équipe multidisciplinaire avec une thérapie bio-psycho-sociale et un traitement médicamenteux : duloxetine, oxycodone, clonazepam (pour son SJSR), trazodone et zolpidem.

2.2.2

Les examens paracliniques de 2007 à 2010

Aucun des examens suivants n’a mis en évidence une maladie systémique, vasculaire ou neurologique : analyses biologiques, électromyographie, scintigraphie osseuse, radiographies de la hanche et des genoux, IRM du cerveau et de la moelle épinière et potentiels évoqués sensitifs et moteurs.

L’évaluation quantitative sensorielle par thermotest selon la méthode des limites réalisée en 2007 montrait des anomalies telles qu’une allodynie diffuse et sévère au froid et à la chaleur. Les potentiels évoqués nociceptifs par stimulation laser ne rapportaient aucune anomalie du traitement central des informations nociceptives.

Cependant en mai 2008, le thermotest montrait des seuils de perception de la chaleur et du froid élevés, l’absence d’allodynie diffuse au froid et à la chaleur mais à la place, l’apparition d’une hyporéactivité généralisée au froid et à la chaleur. Les potentiels évoqués nociceptifs par stimulation laser montraient une réaction normale pour les afférences somesthésiques et thermonociceptives mais un dysfonctionnement dans le traitement central des informations nociceptives.

Une analyse de la marche a été réalisée en 2007. Nous avons utilisé un tapis roulant (Mercury LTmed, HPCosmos, Allemagne), avec une courroie appropriée (1500 mm de long × 500 mm de large) et une puissance moteur suffisante (2,2 kW). Le système de contrôle permettait une vitesse constante allant de 1 à 22 km/h (par paliers minimum de 0,1 km/h). Une analyse cinématique segmentaire était conduite avec le système Élite (BTS, Italie) à 100 Hz. Six caméras à infrarouges mesuraient les coordonnées tridimensionnelles de 20 marqueurs réflectifs positionnés sur des repères anatomiques précis. À partir des angles d’Euler, cette analyse permettait de calculer les déplacements angulaires du pelvis, hanches, genoux et chevilles dans les trois dimensions. Les angles articulaires étaient mesurés selon la méthode classique utilisée lors d’examens cliniques. La position neutre de l’articulation étant de 0°. Les valeurs négatives correspondent à l’extension sur le plan sagittal ou médian, abduction sur le plan frontal et rotation externe sur le plan transversal. Contrairement aux valeurs positives, qui elles correspondaient à une flexion sur le plan sagittal, adduction sur le plan frontal et rotation interne sur le plan transversal. Deux marqueurs placés sur les cinquièmes métatarses ont permis de déterminer les contacts du pied avec le sol, et la courbe de vitesse selon la méthode décrite par Mickelborough et al. La fréquence du pas et la durée de la phase d’appui étaient dérivées de ces périodes de contact du pied avec le sol. Les forces de réaction du sol étaient mesurées à l’aide de quatre capteurs de force installés sous chaque coin du tapis roulant. Ce tapis roulant avec capteurs de mesure correspondait à une plateforme unique, enregistrant les forces de réaction globale du sol. L’algorithme décrit par Davis et Cavanagh permet de définir la position du centre de pression du pied et la composante verticale de la force de réaction du sol sous chaque pied, en séparant la force de réaction du sol entre les capteurs de gauche et de droite et ceux devant et derrière. La composante horizontale de la force de réaction du sol était également décomposée. Durant la phase d’appui unipodal, la composante horizontale de chaque force, pour chacun des quatre capteurs, était notée et ensuite additionnée aux autres, le résultat était similaire à celui obtenu pour une marche au sol. Durant la phase d’appui bipodal, les données de force recueillies par les deux capteurs de gauche étaient séparées des données de force des deux capteurs de droite afin de définir la force sous chaque pied, gauche et droit. En utilisant une approche dynamique inversée, les forces de réaction du sol, la cinématique et les données anthropométriques, nous avons pu définir le moment articulaire pour la hanche, le genou et la cheville dans le plan sagittal. La puissance articulaire était définie pour chaque articulation comme le produit de la vitesse angulaire et du moment articulaire .

Il n’a pas été possible de mesurer la raideur musculaire des chevilles à cause des difficultés d’installation de la patiente sur l’appareil de mesure. L’examen EMG télémétrique (EMG system – Telemg, BTS, Italie) avec des électrodes de surface (Medi-Trace, Graphic Controls Corporation, NY, États-Unis) a permis de mesurer l’activité électrique des muscles suivants : quadriceps femoris , biceps femoris , tibialis anterior et gastrocnemius lateralis . Le signal était digitalisé puis amplifié à 1000 Hz, puis rectifié et filtré (fréquence 25–300 Hz). Le début et la fin de l’activation musculaire étaient déterminés visuellement et de façon mathématique en calculant le seuil d’intensité EMG nécessaire à l’activation comme décrit par Van Boxtel et al. .

La patiente marchait sur le tapis roulant à une vitesse constante de 1,4 km/h et ensuite passait à une vitesse de 2,5 km/h. Les résultats étaient ensuite comparés aux valeurs collectées auprès d’une population saine et à la même vitesse. L’analyse de la marche montre des paramètres dans les normes ( Fig. 1 ), particulièrement le ratio cadence du pas/longueur du pas qui était normal, contrairement aux valeurs obtenues chez des patients souffrant de diplégie spastique.