This article describes the features of Japanese dysphagia rehabilitation, particularly where it differs from that in the United States. Many kinds of professionals participate in dysphagia rehabilitation; nurses and dental associates take important roles, and the Japanese insurance system covers that. Videofluorography and videoendoscopy are common and are sometimes done by dentists. Intermittent catheterization is applied to nutrition control in some cases. The balloon expansion method is applied to reduce pharyngeal residue after swallowing. If long-term rehabilitation does not work effectively in dysphagia due to brainstem disorder, the authors consider reconstructive surgery to improve function.

Dysphagia is one of the most important targets for rehabilitation in Japan. The Japanese have the highest rates of life expectancy in the world, at 79 years for men and 85 years for women in 2007. Elderly people (aged 60 or over) comprised 26.3% of the Japanese population in 2005, and that figure is expected to grow to 41.7% by 2050 ( Table 1 ). The population covered by long-term care insurance was 2,259,000 in 2004. The aging of the Japanese population is expected to raise the prevalence of dysphagia.

| Japan | United States | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2005 | 2050 | 2005 | 2050 |

| Population 60+ a (%) | 128,085 (26.3) | 115,710 (41.7) | 298,213 (16.7) | 350,103 (26.4) |

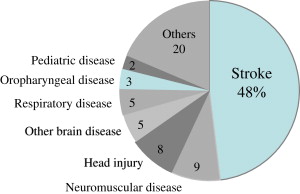

The top four causes of death in Japanese are malignant neoplasm (30.1%), heart disease (16%), stroke (12.3%), and pneumonia (9.9%). Stroke is one of the most common causes of dysphagia. Fig. 1 shows the disease of patients who underwent videofluorographic examinations in the authors’ department over the past 10 years. As causes of dysphagia, stroke accounts for 45% of them.

The prevalence of stroke in Japan is higher than in the United States, at approximately 400 per 100,000 or 1.6 times that of the United States . The rate of ischemic stroke in Japan is about 78%, and hemorrhage is 15.5% . In the case of infarction, we have many cases of brainstem disorders . Therefore, many patients have dysphagia due to bulbar palsy. When pneumonia is the cause of death, aspiration pneumonia of the elderly is the most important factor. The authors believe that not fewer than 50% of cases of pneumonia in the elderly are caused by aspiration .

Clinical circumstance in Japanese rehabilitation

When we compare Japanese dysphagia rehabilitation with that of Europe and the Unites States, we should think about the difference of length of hospital stay. The Japanese insurance system covers long periods of inpatient treatment. For example, in the case of stroke, the Japanese insurance system allows acute care for 2 or 3 weeks, after which care in the rehabilitation unit is covered for up to 180 days if necessary. The legally approved rehabilitation unit provides up to 180 minutes of exercise per day. In this way, Japanese rehabilitation consists of an inpatient system from the acute phase to the subacute phase and dysphagia rehabilitation is managed under these circumstances. In contrast, for cases of chronic disease such as Parkinson disease or neuromuscular diseases, the insurance system does not cover treatment in the rehabilitation unit. It is difficult to manage dysphagia rehabilitation for chronic patients.

In 2006, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare introduced a new insurance system for the care of dysphagia called “eating function therapy.” The insurance covers exercise or care for 30 minutes by nurses, dental hygienists, or therapists. This change was significant because the insurance pays for exercise therapy done by nontherapists and the insurance can cover the rehabilitation exercise done by therapists and the eating function therapy together, so that the insurance-covered exercise time for the dysphagic patient became 30 minutes longer.

Although dysphagia rehabilitation in the United States is managed mainly by speech language pathologists, it is different from that in the authors’ country. In Japan, many kinds of professionals join dysphagia rehabilitation clinics and research. Although speech therapists undertake an important role, nurses also take a major role in the dysphagia rehabilitation associated with the eating function therapy. The Japanese Nursing Association has managed the Training School for Dysphagia Rehabilitation Nursing since 2007. They offer paid educational lectures and clinical training for 1 year and provide a certification program as a certified dysphagia rehabilitation nurse through evaluation tests. Sixty nurses are certified every year.

Dentists and dental hygienists also play an important role in dysphagia rehabilitation. Some dentists make a diagnosis and evaluation of dysphagia using videoendoscopy or videofluorography. The importance of oral care is well known in Japan. Some acute care units or rehabilitation units have dental treatment teams. They treat oral problems to reduce the incidence of aspiration pneumonia and cooperate with medical doctors to improve eating function. Otolaryngologists in Japan have done extensive research on dysphagia and swallowing for a long time. They offer aggressive surgical treatment of dysphagia.

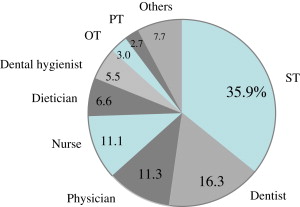

Physiatrists play a primary role in the evaluation and management of dysphagia rehabilitation from the viewpoint of kinesiology with the use of videofluorography. Speech therapy involves intensive exercise treatment, as in other countries. Fig. 2 shows the composition of the Japanese Society of Dysphagia Rehabilitation (JSDR) members. It reflects the features of an actual transdisciplinary rehabilitation team.

Diagnostic techniques

Several diagnostic techniques have been developed in Japan to detect swallowing problems without videofluorography or videoendoscopy.

The repetitive saliva swallowing test (RSST) is one of the most well known methods . This screening test detects patient who have aspiration. The patient is asked to do saliva (dry) swallows as many times as possible in 30 seconds. If the patient does not swallow three times repetitively, he or she is likely to have dysphagia associated with aspiration. The sensitivity and specificity of the RSST to detect aspiration diagnosed by videofluorography are 0.98 and 0.66, respectively .

The modified water swallowing test and the food test were also developed in Japan . These tests are easy and safe methods to evaluate swallowing function or a temporal change in the function.

The authors consider videofluorography to be the most important technique for the diagnosis and evaluation of dysphagia and in formulating a plan of dysphagia rehabilitation. The JSDR provides a guide for standardized performance of videofluorography. The standard method emphasizes that one should use an appropriate chair to control the examinee’s posture, should prepare appropriate test foods, and must know the compensatory swallowing maneuvers. A physician or dentist does the videofluorography, and therapists often join it. The fee for videofluorography is up to $60, which is inexpensive compared with that in the United States.

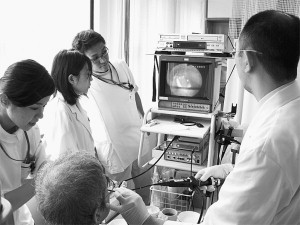

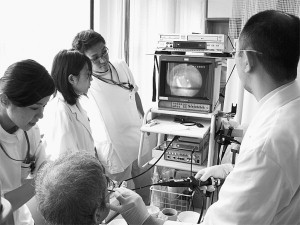

The authors often apply transnasal flexible videoendoscopy for evaluation at the bedside or in a home visit but this procedure may be performed only by physicians or dentists in Japan ( Fig. 3 ). Although dentists are permitted to do videoendoscopy by law, insurance sometimes does not cover it. The fee for videofluorography done by a physician is approximately $60.

Diagnostic techniques

Several diagnostic techniques have been developed in Japan to detect swallowing problems without videofluorography or videoendoscopy.

The repetitive saliva swallowing test (RSST) is one of the most well known methods . This screening test detects patient who have aspiration. The patient is asked to do saliva (dry) swallows as many times as possible in 30 seconds. If the patient does not swallow three times repetitively, he or she is likely to have dysphagia associated with aspiration. The sensitivity and specificity of the RSST to detect aspiration diagnosed by videofluorography are 0.98 and 0.66, respectively .

The modified water swallowing test and the food test were also developed in Japan . These tests are easy and safe methods to evaluate swallowing function or a temporal change in the function.

The authors consider videofluorography to be the most important technique for the diagnosis and evaluation of dysphagia and in formulating a plan of dysphagia rehabilitation. The JSDR provides a guide for standardized performance of videofluorography. The standard method emphasizes that one should use an appropriate chair to control the examinee’s posture, should prepare appropriate test foods, and must know the compensatory swallowing maneuvers. A physician or dentist does the videofluorography, and therapists often join it. The fee for videofluorography is up to $60, which is inexpensive compared with that in the United States.

The authors often apply transnasal flexible videoendoscopy for evaluation at the bedside or in a home visit but this procedure may be performed only by physicians or dentists in Japan ( Fig. 3 ). Although dentists are permitted to do videoendoscopy by law, insurance sometimes does not cover it. The fee for videofluorography done by a physician is approximately $60.

Treatment or exercise

Nutrition management

The importance of nutritional management during the acute phase of illness is understood, so many hospitals have introduced nutrition support teams. But dysphagia rehabilitation on these teams is less well understood. Currently, the JSDR and the Japanese Society for Parental and Enteral Nutrition (JSPEN) are collaborating to improve this situation. The JSDR conducts a lecture about dysphagia rehabilitation at the annual meeting of the JSPEN, and the JSPEN conducts a lecture about nutritional management at the annual JSDR meeting.

The important methods of enteral nutrition are nasogastric tube and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). PEG has become a common method in Japan but some misunderstanding exists. PEG is not a goal of nutritional management but rather, just a method of nutritional management. When PEG is completed and nutritional status is improved, one then has to begin constructive rehabilitation programs. The authors have extensive experience indicating that patients who have undergone PEG placement can subsequently improve their swallowing function through appropriate rehabilitation and nutritional control after PEG, and are finally able to quit the gastrostomy feeding. Although PEG has become common, the timing of PEG placement is comparatively late in Japan (several months after the onset of dysphagia), so a long period of nutritional management is done by nasogastric tube.

Intermittent catheterization is a unique method of nutritional management in Japan. This method is one in which the patient inserts his or her own feeding tube on demand per oral or nasal route, infuses an enteral nutrient, and, when finished infusing, immediately removes the tube. If the patient has good mental status and communication, this method can be applied easily without risk for aberrant tube placement in the airway. If the patient has a good esophageal function shown by videofluorography, a tip of the tube can be put at the middle of the esophagus, causing secondary peristalsis in the esophagus. The authors believe that this peristalsis induces the esophagogastric reflex and must be more physiologic than PEG tube feeding. This technique will work to reduce gastroesophageal reflux or diarrhea. The greatest benefit of this method is the opportunity to be tube free for periods during each day, and direct therapy exercise can be managed easily for intermittent catheterization patients.

Oral care

Oral care is recognized as an essential aspect of dysphagia rehabilitation in Japan. The Japanese Dental Association works to help dentists and dental-associated persons understand the importance of oral care for disabled persons, and it has educational programs on this topic in the community. Several important studies have been managed by collaborations between Japanese dentists and physicians. One important study showed that the oral hygiene of disabled people admitted to a subacute rehabilitation hospital was poor, and treatment by a dentist and dental hygienist led to improvements not only in the patients’ oral condition but also in their activities of daily living and eating ability . Another article reported that the oral care treatment of the disabled elderly in nursing homes reduced the incidence of aspiration pneumonia . A study regarding the effects of oral care and functional training on entirely tube-fed patients showed that professional oral care and indirect therapy by a dental hygienist once weekly was sufficient to maintain oral hygiene and reduce the incidence of pneumonia .

Indirect therapy

Indirect therapy for dysphagia is widely practiced, as discussed elsewhere in this issue. The authors apply many kinds of methods, including respiratory exercise or range-of-motion exercise for the neck or around the shoulder. These days, they often apply the head-raising exercise developed by Shaker and colleagues to many kinds of dysphagia (with some technical modifications). The authors understand that the exercise strengthens the hyolaryngeal elevator muscles as demonstrated by Shaker’s randomized control study. They now call the exercise “Shaker exercise” and it is quite popular in Japan.

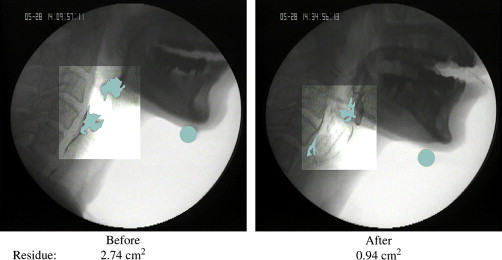

The authors sometimes apply balloon expansion of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) for dysphagia in cases with large amounts of pharyngeal retention after swallowing . The pharyngeal retention generally results from UES dysfunction or poor pharyngeal constriction. Therefore, when the authors find pharyngeal retention on videofluorography, they sometimes stretch the UES using a catheter that has a balloon (as in a standard urethral catheter) placed through the oral cavity. This method has a diagnostic usefulness; when a floppy UES is identified, they know that the retention may be caused by poor pharyngeal constrictors, but if the UES is tight, the retention may be caused by UES dysfunction. In any case, when the authors find that the balloon-expanding method reduces retention after swallowing, and the patient has no difficulty (such as pain or gagging), they apply balloon expansion as an indirect therapy for dysphagia ( Fig. 4 ). Although the long-term effect of this method may vary from case to case, some cases show obvious benefit, and the authors know of no reported ill effects with this method when treating functional dysphagia. Therefore, they do not hesitate to try this method.